You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (September 2016) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Jean-Marie-Mathias-Philippe-Auguste, comte de Villiers de l'Isle-Adam[1] (7 November 1838 – 19 August 1889) was a French symbolist writer. His family called him Mathias while his friends called him Villiers; he would also use the name Auguste when publishing some of his books.

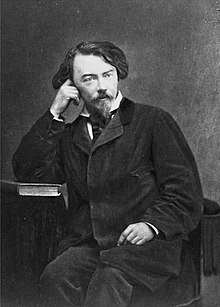

Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam | |

|---|---|

Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam in 1886 | |

| Born | Jean-Marie-Mathias-Philippe-Auguste de Villiers de L'Isle-Adam 7 November 1838 Saint-Brieuc, France |

| Died | 19 August 1889 (aged 50) Paris, France |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | French |

| Nationality | French |

| Literary movement | |

| Notable works | The Future Eve (1886) |

| Signature | |

| |

Life

editVilliers de l'Isle-Adam was born in Saint-Brieuc, Brittany, to a distinguished aristocratic family. His parents, Marquis Joseph-Toussaint and Marie-Francoise (née Le Nepvou de Carfort) were not financially secure and were supported by Marie's aunt, Mademoiselle de Kerinou. In attempt to gain wealth, Villiers de l'Isle-Adam's father began an obsessive search for the lost treasure of the Knights of Malta, formerly known as the Knights Hospitaller, of which order Philippe Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, a family ancestor, was the 16th-century Grand Master. The treasure had reputedly been buried near Quintin during the French Revolution. Consequently, Marquis Joseph-Toussaint spent large sums of money buying and excavating land before selling unsuccessful sites at a loss.

The young Villiers' education was troubled—he attended over half a dozen different schools—yet from an early age his family were convinced he was an artistic genius, and as a child, he composed poetry and music. A significant event in his childhood years was the death of a young girl with whom Villiers had been in love, an event which would deeply influence his literary imagination.

Villiers made several trips to Paris in the late 1850s, where he became enamoured of artistic and theatrical life. In 1860, his aunt offered him enough money to allow him to live in the capital permanently. He had already acquired a reputation in literary circles for his inspired, alcohol-fuelled monologues. He frequented the Brasserie des Martyrs, where he met his idol Baudelaire, who encouraged him to read the works of Edgar Allan Poe. Poe and Baudelaire would become the biggest influences on Villiers' mature style; his first publication, however (at his own expense), was a book of verse, Premières Poésies (1859). It made little impression outside Villiers' own small band of admirers. Around this time, Villiers began living with Louise Dyonnet. The relationship and Dyonnet's reputation scandalised his family; they forced him to undergo a retreat at Solesmes Abbey. Villiers would remain a devout, if highly unorthodox, Catholic for the rest of his life.

Villiers broke off his relationship with Dyonnet in 1864. He made several further attempts at securing a suitable bride, but all ended in failure. In 1867, he asked Théophile Gautier for the hand of his daughter, Estelle, but Gautier — who had turned his back on the bohemian world of his youth and would not let his child marry a writer with few prospects — turned him down. Villiers' own family also strongly disapproved of the match. His plans for marriage to an English heiress, Anna Eyre Powell, were equally unsuccessful. Villiers finally took to living with Marie Dantine, the illiterate widow of a Belgian coachman. In 1881, she gave birth to Villiers' son, Victor (nicknamed "Totor").

An important event in Villiers' life was his meeting with Richard Wagner at Triebschen in 1869. Villiers read from the manuscript of his play La Révolte and the composer declared that the Frenchman was a "true poet".[2] Another trip to see Wagner the next year was cut short by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, during which Villiers became a commander in the Garde Nationale. At first, he was impressed by the patriotic spirit of the Commune and wrote articles in support of it in the Tribun du peuple under the pseudonym "Marius", but he soon became disillusioned with its revolutionary violence.

Villiers' aunt died in 1871, ending his financial support. Though Villiers had many admirers in literary circles (the most important being his close friend Stéphane Mallarmé), mainstream newspapers found his fiction too eccentric to be saleable, and few theatres would run his plays. Villiers was forced to take odd jobs to support his family: he gave boxing lessons and worked in a funeral parlour and was employed as an assistant to a mountebank. Another money-making scheme Villiers considered was reciting his poetry to a paying public in a cage full of tigers, but he never acted on the idea. According to his friend Léon Bloy, Villiers was so poor he had to write most of his novel L'Ève future lying on his belly on bare floorboards, because the bailiffs had taken all his furniture. His poverty only increased his sense of aristocratic pride.

In 1875, he attempted to sue a playwright he believed had insulted one of his ancestors, Maréchal Jean de Villiers de l'Isle-Adam. In 1881, Villiers stood unsuccessfully for parliament as a candidate for the Legitimist party. By the 1880s Villiers' fame began to grow, but not his finances. The publishers Calmann-Lévy accepted his Contes cruels, but the sum they offered Villiers was negligible. The volume did, however, come to the attention of Joris-Karl Huysmans, who praised Villiers's work in his highly influential novel À rebours. By this time, Villiers was very ill with stomach cancer. On his deathbed, he finally married Marie Dantine, thus legitimising his beloved son "Totor". He is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery, though a planned tomb monument designed by Frédéric Brou was abandoned at the maquette stage.

Writings

editVilliers' works, in the Romantic style, are often fantastic in plot and filled with mystery and horror. Important among them are the drama Axël (1890), the novel The Future Eve (1886), and the short-story collection Contes cruels (1883, tr. Sardonic Tales, 1927). Contes cruels is regarded as an important collection of horror stories, and the origin of the short story genre conte cruel.[3] The Future Eve greatly helped to popularize the term "android" (Androïde in French, the character is named "Andréide").[4]

Villiers believed the imagination has within it much more beauty than reality itself, existing at a level in which nothing real could compare.

Axël

editVilliers considered Axël to be his masterpiece, although critics preferred his fiction. He began work on the play around 1869, and had still not completed it when he died. It was first published posthumously in 1890. The work is heavily influenced by the Romantic theatre of Victor Hugo, as well as Goethe's Faust and the music dramas of Richard Wagner.

The play's most famous line is Axël's "Vivre? les serviteurs feront cela pour nous" ("Living? Our servants will do that for us"). Edmund Wilson used the title Axel's Castle for his study of early Modernist literature.

Works

edit- Premières Poésies (early verse, 1859; translated into English as Early Poetry by Sunny Lou Publishing, 2024)

- Isis (novel, uncompleted, 1862)

- Elën (drama in three acts in prose, 1865)

- Morgane (drama in five acts in prose, 1866)

- La Révolte (drama in one act, 1870)

- Le Nouveau Monde (drama, 1880)

- Contes Cruels (stories, 1883; translated into English as Sardonic Tales by Hamish Miles in 1927, and as Cruel Tales by Robert Baldick in 1963)

- L'Ève future (novel, 1886; translated into English as Tomorrow's Eve by Robert Martin Adams)

- L'Amour supreme (stories, 1886; partially translated into English by Brian Stableford as The Scaffold and The Vampire Soul)

- Tribulat Bonhomet (fiction including "Claire Lenoir", 1887; translated into English by Brian Stableford as The Vampire Soul ISBN 1-932983-02-3)

- L'Evasion (drama in one act, 1887)

- Histoires insolites (stories, 1888; partially translated into English by Brian Stableford as The Scaffold and The Vampire Soul)

- Nouveaux Contes cruels (stories, 1888; partially translated into English by Brian Stableford as The Scaffold and The Vampire Soul)

- Chez les passants (stories, miscellaneous journalism, 1890)

- Axël (published posthumously 1890; translated into English by June Guicharnaud)

Notes

edit- ^ French: [ʒɑ̃ maʁi matjas filip ɔɡyst kɔ̃t də vilje dəliladɑ̃].

- ^ Jean-Aubry, G. (1938). "Villiers de l'Isle Adam and Music". Music & Letters. 19 (4): 398. doi:10.1093/ml/XIX.4.391. ISSN 0027-4224. JSTOR 727722.

- ^ Ben Indick, "Villiers de l'Isle-Adam, Phillipe August, Comte de", in Sullivan, Jack, (ed.) The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural. p.442. Viking, New York. 1986. ISBN 0-670-80902-0

- ^ Shelde, Per (1993). Androids, Humanoids, and Other Science Fiction Monsters: Science and Soul in Science Fiction Films. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-7930-1

Sources

edit- Jean-Paul Bourre, Villiers de L'Isle Adam: Splendeur et misère (Les Belles Lettres, 2002)

- Natalie Satiat's edition of L'Ève future (Garnier-Flammarion)

External links

edit- Works by Auguste Villiers de L'Isle-Adam at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam at the Internet Archive

- Works by Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Black Coat Press, publisher of American translations of Villiers de l'Isle-Adam.