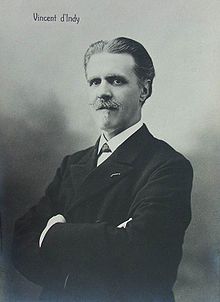

Paul Marie Théodore Vincent d'Indy (French: [vɛ̃sɑ̃ dɛ̃di]; 27 March 1851 – 2 December 1931) was a French composer and teacher. His influence as a teacher, in particular, was considerable. He was a co-founder of the Schola Cantorum de Paris and also taught at the Paris Conservatoire. His students included Albéric Magnard, Albert Roussel, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Yvonne Rokseth, and Erik Satie, as well as Cole Porter.

D'Indy studied under composer César Franck, and was strongly influenced by Franck's admiration for German music. At a time when nationalist feelings were high in both countries (circa the Franco-Prussian War of 1871), this brought Franck into conflict with other musicians who wished to separate French music from German influence.

Life

editPaul Marie Théodore Vincent d'Indy was born in Paris into an aristocratic family of royalist and Catholic persuasion. He had piano lessons from an early age from his paternal grandmother, who passed him on to Antoine François Marmontel and Louis Diémer.[1]

From the age of 14 d'Indy studied harmony with Albert Lavignac. When he was 16 an uncle introduced him to Berlioz's treatise on orchestration, which inspired him to become a composer.[2] He wrote a piano quartet which he sent to César Franck, who was the teacher of a friend. Franck recognised his talent and recommended that d'Indy pursue a career as a composer.[2]

At the age of 19, during the Franco-Prussian War, d'Indy enlisted in the National Guard, but returned to musical life as soon as the hostilities were over. He entered Franck's organ class at the Conservatoire de Paris in 1871 remaining there until 1875, when he joined the percussion section of the orchestra at the Châtelet Theatre to gain practical experience. He also served as chorus-master to the Concerts Colonne.[2]

The first of his works he heard performed was a Symphonie italienne, at an orchestral rehearsal under Jules Pasdeloup; the work was admired by Georges Bizet and Jules Massenet, with whom he had already become acquainted.[1]

During the summer of 1873 he visited Germany, where he met Franz Liszt and Johannes Brahms. On 25 January 1874, his overture Les Piccolomini was performed at a Pasdeloup concert, sandwiched between works by Bach and Beethoven.[1] Around this time he married Isabelle de Pampelonne, one of his cousins. In 1875 his symphony dedicated to János Hunyadi was performed. That same year he played a minor role – the prompter – at the premiere of Bizet's opera Carmen.[1] In 1876 he was present at the first production of Richard Wagner's Ring cycle at Bayreuth. This made a great impression on him and he became a fervent Wagnerian.[3]

In 1878 d'Indy's symphonic ballad La Forêt enchantée was performed.[4] In 1882 he heard Wagner's Parsifal. In 1883 his choral work Le Chant de la cloche appeared. In 1884 his symphonic poem Saugefleurie was premiered. His piano suite ("symphonic poem for piano") called Poème des montagnes came from around this time. In 1887 appeared his Suite in D for trumpet, 2 flutes and string quartet. That same year he was involved in Lamoureux's production of Wagner's Lohengrin as choirmaster. His music drama Fervaal occupied him between 1889 and 1895.[3]

Inspired by his studies with Franck and yet dissatisfied with the standard of teaching at the Conservatoire, d'Indy, together with Charles Bordes and Alexandre Guilmant, founded the Schola Cantorum de Paris in 1894.[3] D'Indy taught there until his death, becoming principal in 1904.[3] Of the teaching at the Schola Cantorum, The Oxford Companion to Music says, "A solid grounding in technique was encouraged, rather than originality", and comments that few graduates could stand comparison with the best Conservatoire students.[5] D'Indy later taught at the Conservatoire and privately, while retaining his post at the Schola Cantorum.[3]

Among d'Indy's renowned pupils were Albéric Magnard, Albert Roussel, Joseph Canteloube (who later wrote d'Indy's biography), Celia Torra,[6] Arthur Honegger and Darius Milhaud.[n 1] Two atypical students were Cole Porter, who signed up for a two-year course at the Schola, but left after a few months,[7] and Erik Satie, who studied there for three years and later wrote, "Why on earth had I gone to d'Indy? The things I had written before were so full of charm. And now? What nonsense! What dullness!"[8] Nonetheless, according to Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, d'Indy's influence as a teacher was "enormous and wide-ranging, with benefits for French music far outweighing the charges of dogmatism and political intolerance".[3]

D'Indy played an important part in the history of the Société nationale de musique, of which his teacher, Franck, had been a founding member in 1871.[9] Like Franck, d'Indy revered German music, and he resented the society's exclusion of non-French music and composers.[9] He became the society's joint secretary in 1885,[3] and succeeded in overturning its French-only rule the following year. The founders of the society, Romain Bussine and Camille Saint-Saëns resigned in protest.[9] Franck refused the formal title of president of the society, but when he died in 1890, d'Indy took the post. His regime, however, alienated a younger generation of French composers, who, led by Maurice Ravel, founded the breakaway Société musicale indépendante in 1910, which attracted leading young composers from France and other countries.[10] In an attempt to further a proposed merger of the two organisations during the First World War d'Indy stepped down as president of the Société nationale to make way for the more "progressive" Gabriel Fauré, but the plan came to nothing.[10]

According to the biographer Robert Orledge, the death of d'Indy's first wife in 1905 removed the stabilising influence in the composer's life, and he became "increasingly vulnerable to politically motivated attacks on the Schola Cantorum and apprehensive of dangerously decadent trends in contemporary music in both France and Germany". His aesthetic ideas, Orledge argues, became "increasingly reactionary and dogmatic" and his political views right-wing and anti-Semitic. He joined the Ligue de la patrie française (League of the French Fatherland) during the Dreyfus affair.[3]

During the First World War d'Indy served on cultural missions to allied countries, and completed his third music drama, La Légende de Saint-Christophe, in Orledge's view "a celebration of traditional Catholic regionalism as opposed to modern liberal democracy and capitalist values".[3] After the war he increased his activities as a conductor, giving concert tours throughout Europe and the US. 1920 he married the much younger Caroline Janson; Orledge writes that this "brought a true creative rebirth, witnessed in the serene Mediterranean-inspired compositions of his final decade".[3]

D'Indy died on 2 December 1931 in his native Paris, aged 80, and was buried in the Montparnasse Cemetery.[11]

Works

editFew of d'Indy's works are performed regularly in concert halls today. Grove comments that his famed veneration for Beethoven and Franck "has unfortunately obscured the individual character of his own compositions, particularly his fine orchestral pieces descriptive of southern France".[3] Among his best known pieces are the Symphony on a French Mountain Air for piano and orchestra (1886), and Istar (1896), a symphonic poem in the form of a set of variations in which the theme appears only at the end.[1]

Among d'Indy's other works are more orchestral pieces, including a Symphony in B♭, a vast symphonic poem, Jour d'été à la montagne, and another, Souvenirs, written on the death of his first wife. The Times said of his music that the influence of Berlioz, Franck, and Wagner is strong in almost all his work, "that of Franck showing itself chiefly in the shapes of his tunes, that of Wagner in their development, and that of Berlioz in their orchestration".[2]

Grove says of his chamber works: "D'Indy's somewhat academic corpus of chamber music (including three completed string quartets) is generally less interesting than his orchestral works". He also wrote piano music (including a Sonata in E minor), songs and a number of operas, including Fervaal (1897) and L'Étranger (1902). His music drama Le Légende de Saint Christophe, based on themes from Gregorian chant, was premiered at the Paris Opéra on 6 June 1920.[2][3]

D'Indy helped revive a number of then largely forgotten Baroque works, for example making his own edition of Monteverdi's opera L'incoronazione di Poppea.[3] D'Indy also contributed to the incipient revival of the works of Antonio Vivaldi, whose sonatas for cello and basso continuo (op. 14) were edited by d'Indy as cello concerti and published by Maurice Senart in 1922.[12] His musical writings include the three-volume Cours de composition musicale as well as studies of Franck and Beethoven.[3] The Times commented that his study of the former was "one of the most vivid and individual of modern French biographies", and the latter, published in 1912, showed "the closeness of the lifelong study which he devoted to that master".[2]

Commemorations

editThe private music college École de musique Vincent-d'Indy in Montreal, Canada, is named after the composer,[13] as is the asteroid 11530 d'Indy, discovered in 1992.[14]

Notes, references and sources

editNotes

edit- ^ Other students included Pierre Capdevielle, Léon Destroismaisons, Déodat de Séverac, Eugène Lapierre, Leevi Madetoja, Rodolphe Mathieu, Helena Munktell, Ahmet Adnan Saygun, Anne Terrier Laffaille, Emiliana de Zubeldia and Xian Xinghai.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e "Indy, Vincent d'",Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th edition, 1954, volume V, Eric Blom ed.

- ^ a b c d e f "M. Vincent d'Indy", The Times, 4 December 1931, p. 16

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Orledge, Robert, and Andrew Thomson. "Indy, (Paul Marie Théodore) Vincent d'", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001 (subscription required)

- ^ "Courrier des théâtres", Le Figaro, 22 March 1878, p. 3

- ^ "Schola Cantorum", The Oxford Companion to Music, edited by Alison Latham, Oxford University Press, 2011.

- ^ Cohen, Aaron I. (1987). International encyclopedia of women composers (Second edition, revised and enlarged ed.). New York. ISBN 0-9617485-2-4. OCLC 16714846.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ McBrien, p 94; and Citron, p. 56

- ^ Templier, p. 32

- ^ a b c Cochard, Alain. "150ème anniversaire de la naissance de la Société nationale de musique", Concertclassic.com. Retrieved 13 May 2021

- ^ a b Duchesneau, Michel. "Maurice Ravel et la Société Musicale Indépendante: 'Projet Mirifique de Concerts Scandaleux'", Revue de Musicologie, vol. 80, no. 2, 1994, pp. 251–281 (subscription required); and "La musique française pendant la Guerre 1914–1918: Autour de la tentative de fusion de la Société Nationale de Musique et de la Société Musicale Indépendante", Revue de Musicologie, 1996, T. 82, No. 1, p. 148 (subscription required)

- ^ "Les obsèques de Vincent d'Indy", Comoedia, 5 December 1931, p. 2

- ^ Sonates en concert: Sonate 5, Paris: Senart, 1922, OCLC 1114800864, retrieved 18 July 2022

- ^ "Historique", École de musique Vincent-d'Indy, 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021

- ^ "(11530) d'Indy", International Astronomical Union Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 15 May 2021

Sources

edit- Blom, Eric (1954). Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (fifth ed.). New York: St Martin's Press. OCLC 1192249.

- Citron, Stephen (1993). Noël and Cole: The Sophisticates. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508385-9.

- McBrien, William (1998). Cole Porter. New York: Knopf. OCLC 1148597196.

- Templier, Pierre-Daniel (1969). Erik Satie. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. OCLC 1034659768.

Further reading

edit- Norman Demuth, Vincent d'Indy: Champion of Classicism (London, 1951)

- Steven Huebner, Vincent d'Indy and Moral Order' and 'Fervaal': French Opera at the Fin de Siècle (Oxford, 1999), pp. 301–08 and 317–50

- Vincent d'Indy (Marie d'Indy, ed.), Vincent d'Indy: Ma Vie. Journal de jeunesse. Correspondance familiale et intime, 1851–1931 (Paris, 2001). ISBN 2-84049-240-7

- James Ross, 'D'Indy's "Fervaal": Reconstructing French Identity at the Fin-de-Siècle', Music and Letters 84/2 (May 2003), pp. 209–40

- Manuela Schwartz (ed.), Vincent d'Indy et son temps (Sprimont, 2006). ISBN 2-87009-888-X

- Andrew Thomson, Vincent d'Indy and his World (Oxford, 1996)

- Robert Trumble, Vincent d'Indy: His Greatness and Integrity (Melbourne, 1994)

- Huebner, Steven (2006). French Opera at the Fin de Siècle: Vincent d'Indy. Oxford Univ. Press, US. pp. 301–350. ISBN 978-0-19-518954-4.

External links

edit- Works by or about Vincent d'Indy at the Internet Archive

- D'Indy Trio for Clarinet, Cello & Piano, Op. 29, Piano Quartet Op. 7, String Quartet No. 1 and String Sextet, Op. 92 soundbites and discussion of works

- Free scores by Vincent d'Indy at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Vincent d'Indy in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Performance of Lied for cello and orchestra on YouTube by Julian Lloyd Webber and the English Chamber Orchestra conducted by Yan Pascal Tortelier