Waco (/ˈweɪkoʊ/ WAY-koh) is a city in and the county seat of McLennan County, Texas, United States.[8] It is situated along the Brazos River and I-35, halfway between Dallas and Austin. The city had a U.S. census estimated 2023 population of 144,816, making it the 24th-most populous city in the state.[9][10] The Waco metropolitan statistical area consists of McLennan, Falls and Bosque counties, which had a 2020 population of 295,782.[11] Bosque County was added to the Waco MSA in 2023. The 2023 U.S. census population estimate for the Waco metropolitan area was 304,865 residents.[12]

Waco | |

|---|---|

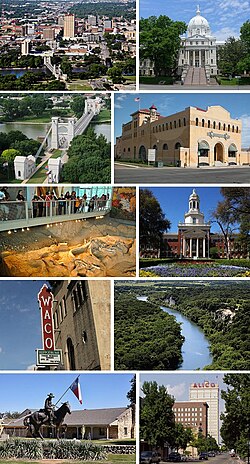

From left to right, top to bottom: Downtown, McLennan County Courthouse, Waco Suspension Bridge, Dr. Pepper Museum, Waco Mammoth National Monument, Baylor University, Waco Hippodrome, Cameron Park, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, and Austin Avenue in Downtown | |

| Nickname(s): "Heart of Texas" "Buckle of the Bible Belt"[1] | |

Location within McLennan County and Texas | |

| Coordinates: 31°33′5″N 97°9′21″W / 31.55139°N 97.15583°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | McLennan |

| Named for | The Waco people |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| Area | |

• City | 101.15 sq mi (261.98 km2) |

| • Land | 88.73 sq mi (229.82 km2) |

| • Water | 12.42 sq mi (32.16 km2) 11.85% |

| Elevation | 522 ft (159 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 138,486 |

• Estimate (2023)[4] | 144,816 |

| • Density | 1,569.16/sq mi (605.86/km2) |

| • Urban | 192,844 (US: 201st) |

| • Urban density | 2,145.6/sq mi (828.4/km2) |

| • Metro | 304,865 (US: 168th) |

| Demonym | Wacoan |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | $27.539 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (Central) |

| ZIP Codes | 76701-76708, 76710-76712, 76714-76716, 76797-76799 |

| Area code | 254 |

| FIPS code | 48-76000[7] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2412162[3] |

| Website | Waco-Texas.com |

History

edit1824–1865

editIndigenous peoples occupied areas along the river for thousands of years. In historic times, the area of present-day Waco was occupied by the Wichita Indian tribe known as the "Waco" (Spanish: Hueco or Huaco).

In 1824, Thomas M. Duke was sent to explore the area after violence erupted between the Waco people and the European settlers. His report to Stephen F. Austin, described the Waco village:[13]

This town is situated on the West Bank of the river. They have a spring almost as cold as ice itself. All we want is some Brandy and Sugar to have Ice Toddy. They have about 400 acres (1.6 km2) planted in corn, beans, pumpkins, and melons and that tended in good order. I think they cannot raise more than One Hundred Warriors.

— Thomas M. Duke, Stephen F. Austin Papers

After further violence, Austin halted an attempt to destroy their village in retaliation. In 1825, he made a treaty with them. The Waco were eventually pushed out of the region, settling north near present-day Fort Worth. In 1872, they were moved onto a reservation in Oklahoma with other Wichita tribes. In 1902, the Waco received allotments of land and became official US citizens. Neil McLennan settled in an area near the South Bosque River in 1838.[14] Jacob De Cordova bought McLennan's property[15] and hired a former Texas Ranger and surveyor named George B. Erath to inspect the area.[16] In 1849, Erath designed the first block of the city. Property owners wanted to name the city Lamartine, but Erath convinced them to name the area Waco Village, after the Indians who had lived there.[17] In March 1849, Shapley Prince Ross, the father of future Governor Lawrence Sullivan Ross, built the first house in Waco, a double-log cabin, on a bluff overlooking the springs. His daughter Kate was the first settler child born in Waco. Because of this, Ross is considered to have been the founder of Waco, Texas.[18]

1866–1900

editIn 1866, Waco's leading citizens embarked on an ambitious project to build the first bridge to span the wide Brazos River. They formed the Waco Bridge Company to build the 475-foot (145 m) brick Waco Suspension Bridge, which was completed in 1870. The company commissioned a firm owned by John Augustus Roebling in Trenton, New Jersey, to supply the bridge's cables and steelwork and contracted with Mr. Thomas M. Griffith, a civil engineer based in New York, for the supervisory engineering work.[19] The economic effects of the Waco bridge were immediate and large. The cowboys and cattle-herds following the Chisholm Trail north, crossed the Brazos River at Waco. Some chose to pay the Suspension Bridge toll, while others floated their herds down the river. The population of Waco grew rapidly, as immigrants now had a safe crossing for their horse-drawn carriages and wagons. Since 1971, the bridge has been open only to pedestrian traffic and is in the National Register of Historic Places.

Waco was the original intended western terminus of the Texas and St. Louis Railway, with the town having been reached in 1881.[20] However, the line was extended further west to Gatesville a year later.[21][22] This trackage later became the core of the St. Louis Southwestern Railway Company, commonly known as the Cotton Belt.[23]

In the late 19th century, a red-light district called the "Reservation" grew up in Waco, and prostitution was regulated by the city. The Reservation was suppressed in the early 20th century. In 1885, the soft drink Dr Pepper was invented in Waco at Morrison's Old Corner Drug Store.[24]

In 1845, Baylor University was founded in Independence, Texas. It moved to Waco in 1886 and merged with Waco University, becoming an integral part of the city. The university's Strecker Museum was also the oldest continuously operating museum in the state until it closed in 2003, and the collections moved to the new Mayborn Museum Complex. In 1873, AddRan College was founded by brothers Addison and Randolph Clark in Fort Worth. The school moved to Waco in 1895, changing its name to Add-Ran Christian University and taking up residence in the empty buildings of Waco Female College. Add-Ran changed its name to Texas Christian University in 1902 and left Waco after the school's main building burned down in 1910.[25] TCU was offered a 50-acre (200,000 m2) campus and $200,000 by the city of Fort Worth to relocate there.[25]

Racial segregation was common in Waco. For example, Greenwood Cemetery was established in the 1870s as a segregated burial place. Black graves were divided from white ones by a fence which remained standing until 2016.[26]

In the 1890s, William Cowper Brann published the highly successful Iconoclast newspaper in Waco. One of his targets was Baylor University. Brann revealed Baylor officials had been trafficking South American children recruited by missionaries and making house-servants out of them. Brann was shot in the back by Tom Davis, a Baylor supporter. Brann then wheeled, drew his pistol, and killed Davis. Brann was helped home by his friends, and died there of his wounds.

In 1894, the first Cotton Palace fair and exhibition center was built to reflect the dominant contribution of the agricultural cotton industry in the region. Since the end of the Civil War, cotton had been cultivated in the Brazos and Bosque valleys, and Waco had become known nationwide as a top producer. Over the next 23 years, the annual exposition would welcome over eight million attendees. The opulent building which housed the month-long exhibition was destroyed by fire and rebuilt in 1910. In 1931, the exposition fell prey to the Great Depression, and the building was torn down. However, the annual Cotton Palace Pageant continues, hosted in late April in conjunction with the Brazos River Festival.

On September 15, 1896, "The Crash" took place about 15 miles (24 km) north of Waco. "The Crash at Crush" was a publicity stunt done by the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad company (known as M-K-T or "Katy"), featuring two locomotives intentionally set to a head-on collision. Meant to be a family fun event with food, games, and entertainment, the Crash turned deadly when both boilers exploded simultaneously, sending metal flying in the air. Three people died and dozens were injured.[27]

20th century

editAn African American man named Sank Majors was hanged from the Washington Avenue Bridge by a white mob in 1905. Another man, Jim Lawyer, was attacked with a whip because he objected to the lynching. In both cases the mob was assisted by Texas Rangers.[28]

In 1916, a Black teenager named Jesse Washington was tortured, mutilated, and burned to death in the town square by a mob that seized him from the courthouse, where he had been convicted of murdering a white woman, to which he confessed. About 15,000 spectators, mostly citizens of Waco, were present. The commonly named Waco Horror drew international condemnation and became the cause célèbre of the nascent NAACP's anti-lynching campaign. In 2006, the Waco City Council officially condemned the lynching, which took place without opposition from local political or judicial leaders; the mayor and chief of police were spectators. On the centenary of the lynching, May 15, 2016, the mayor apologized in a ceremony to some of Washington's descendants. A historical marker is being erected.[29]

In the 1920s, despite the popularity of the Ku Klux Klan and high numbers of lynchings throughout Texas, Waco's authorities attempted to respond to the NAACP's campaign and institute more protections for African Americans or others threatened with mob violence and lynching.[30] On May 26, 1922, Jesse Thomas was shot, his body dragged down Franklin street by a crowd some 6,000 strong and the corpse then burned in the public square behind city hall.[31] In 1923, Waco's sheriff Leslie Stegall protected Roy Mitchell, an African American coerced into confessing to multiple murders, from mob lynching. Mitchell was the last Texan to be publicly executed in Texas, and also the last to be hanged before the introduction of the electric chair.[30] In the same year, the Texas Legislature created the Tenth Civil Court of Appeals and placed it in Waco; it is now known as the 10th Court of Appeals.

In 1937, Grover C. Thomsen and R. H. Roark created a soft-drink called "Sun Tang Red Cream Soda". This would become known as the soft drink Big Red.

On May 5, 1942, Waco Army Air Field opened as a basic pilot training school, and on June 10, 1949, the name was changed to Connally Air Force Base in memory of Col. James T. Connally, a local pilot killed in Japan in 1945. The name changed again in 1951 to the James Connally Air Force Base. The base closed in May 1966 and is now the location of Texas State Technical College, formerly Texas State Technical Institute, since 1965. The airfield is still in operation, now known as TSTC Waco Airport, and was used by Air Force One when former US President George W. Bush visited his Prairie Chapel Ranch, also known as the Western White House, in Crawford, Texas.

In 1951, Harold Goodman founded the American Income Life Insurance Company.

On May 11, 1953, a violent F5 tornado hit downtown Waco, killing 114.[32] As of 2011, it remains the 11th-deadliest tornado in U.S. history and tied for the deadliest in Texas state history.[33] It was the first tornado tracked by radar and helped spur the creation of a nationwide storm surveillance system. A granite monument featuring the names of those killed was placed downtown in 2004.[34]

In 1964, the Texas Department of Public Safety designated Waco as the site for the state-designated official museum of the legendary Texas Rangers law enforcement agency founded in 1823. In 1976, it was further designated the official Hall of Fame for the Rangers and renamed the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum. Renovations by the Waco government earned this building green status, the first Waco government-led project of its nature. The construction project has fallen under scrutiny for expanding the building over unmarked human graves.

In 1978, bones were discovered emerging from the mud at the confluence of the Brazos and Bosque Rivers. Excavations revealed the bones were 68,000 years old and belonged to a species of mammoth. Eventually, the remains of at least 24 mammoths, one camel, and one large cat were found at the site, making it one of the largest findings of its kind. Scholars have puzzled over why such a large herd had been killed at once. The bones are on display at the Waco Mammoth National Monument, part of the National Park Service.

Waco siege

editOn February 28, 1993, a shootout occurred in which six Branch Davidians and four agents of the United States Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms died. After 51 days, on April 19, 1993, the standoff ended when the Branch Davidians' facility, referred to as Mt. Carmel, was set ablaze, thirteen miles from Waco.[35] 74 people, including leader David Koresh, died in the blaze.

21st century

editDuring the presidency of George W. Bush, Waco was the home to the White House Press Center. The press center provided briefing and office facilities for the press corps whenever Bush visited his "Western White House" Prairie Chapel Ranch near Crawford, about 25 miles (40 km) northwest of Waco.

On May 17, 2015, a violent dispute among rival biker gangs broke out at Twin Peaks restaurant. The Waco police intervened, with nine dead and 18 injured in the incident. More than 170 were arrested.[36] No bystanders, Twin Peak employees, or officers were killed. This was the most high-profile criminal incident since the Waco siege, and the deadliest shootout in the city's history.

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 95.5 square miles (247 km2), of which 84.2 square miles (218 km2) is land and 11.3 square miles (29 km2) is covered by water. The total area is 11.85% water.

Cityscape

editDowntown Waco is relatively small when compared to other larger Texas cities, such as Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, or even Fort Worth, El Paso, or Austin. The 22-story ALICO Building, completed in 1910, is the tallest building in Waco.[37]

Climate

editWaco experiences a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa), characterized by hot summers and generally mild winters. Some 90 °F (32 °C) temperatures have been observed in every month of the year. The record low temperature is −5 °F (−21 °C), set on January 31, 1949; the record high temperature is 114 °F (46 °C), set on July 23, 2018.[38]

| Climate data for Waco Regional Airport, Texas, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1901–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 90 (32) |

96 (36) |

100 (38) |

101 (38) |

102 (39) |

109 (43) |

114 (46) |

112 (44) |

111 (44) |

104 (40) |

92 (33) |

91 (33) |

114 (46) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 78.3 (25.7) |

81.5 (27.5) |

85.7 (29.8) |

89.9 (32.2) |

94.5 (34.7) |

99.1 (37.3) |

103.0 (39.4) |

103.8 (39.9) |

99.9 (37.7) |

93.6 (34.2) |

84.3 (29.1) |

79.0 (26.1) |

105.1 (40.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 59.1 (15.1) |

63.1 (17.3) |

70.2 (21.2) |

77.9 (25.5) |

85.3 (29.6) |

92.7 (33.7) |

96.7 (35.9) |

97.1 (36.2) |

90.8 (32.7) |

80.7 (27.1) |

68.8 (20.4) |

60.4 (15.8) |

78.6 (25.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 47.4 (8.6) |

51.6 (10.9) |

58.8 (14.9) |

66.2 (19.0) |

74.3 (23.5) |

81.9 (27.7) |

85.6 (29.8) |

85.5 (29.7) |

78.7 (25.9) |

68.4 (20.2) |

57.2 (14.0) |

49.2 (9.6) |

67.1 (19.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 35.8 (2.1) |

40.1 (4.5) |

47.4 (8.6) |

54.6 (12.6) |

63.3 (17.4) |

71.1 (21.7) |

74.4 (23.6) |

73.9 (23.3) |

66.7 (19.3) |

56.2 (13.4) |

45.6 (7.6) |

37.9 (3.3) |

55.6 (13.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 20.6 (−6.3) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

28.4 (−2.0) |

37.2 (2.9) |

47.5 (8.6) |

61.2 (16.2) |

68.1 (20.1) |

66.5 (19.2) |

52.6 (11.4) |

38.2 (3.4) |

27.6 (−2.4) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

18.2 (−7.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −5 (−21) |

−1 (−18) |

15 (−9) |

26 (−3) |

34 (1) |

52 (11) |

58 (14) |

53 (12) |

39 (4) |

25 (−4) |

17 (−8) |

−4 (−20) |

−5 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.59 (66) |

2.68 (68) |

3.31 (84) |

3.30 (84) |

4.44 (113) |

3.35 (85) |

1.82 (46) |

2.05 (52) |

2.87 (73) |

4.41 (112) |

2.71 (69) |

2.87 (73) |

36.40 (925) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.7 (1.75) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.2 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 7.1 | 8.3 | 6.5 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 80.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Source 1: NOAA[39] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[40] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 3,008 | — | |

| 1880 | 7,295 | 142.5% | |

| 1890 | 14,445 | 98.0% | |

| 1900 | 20,686 | 43.2% | |

| 1910 | 26,425 | 27.7% | |

| 1920 | 38,500 | 45.7% | |

| 1930 | 52,848 | 37.3% | |

| 1940 | 55,982 | 5.9% | |

| 1950 | 84,706 | 51.3% | |

| 1960 | 97,808 | 15.5% | |

| 1970 | 95,326 | −2.5% | |

| 1980 | 101,261 | 6.2% | |

| 1990 | 103,590 | 2.3% | |

| 2000 | 113,726 | 9.8% | |

| 2010 | 124,805 | 9.7% | |

| 2020 | 138,486 | 11.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[41] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[42] | Pop 2010[43] | Pop 2020[44] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 58,096 | 57,217 | 58,644 | 51.08% | 45.85% | 42.35% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 25,477 | 26,184 | 26,844 | 22.40% | 20.98% | 19.38% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 307 | 310 | 408 | 0.27% | 0.25% | 0.29% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 1,542 | 2,148 | 3,525 | 1.36% | 1.72% | 2.55% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 43 | 49 | 84 | 0.04% | 0.04% | 0.06% |

| Other Race alone (NH) | 82 | 176 | 704 | 0.07% | 0.14% | 0.51% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 1,294 | 1,774 | 4,420 | 1.14% | 1.42% | 3.19% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 26,885 | 36,947 | 43,857 | 23.64% | 29.60% | 31.67% |

| Total | 113,726 | 124,805 | 138,486 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 138,486 people, 50,108 households, and 29,014 families residing in the city.

At the census of 2010,[7] 124,805 people resided in the city, organized into 51,452 households and 27,115 families. The population density was recorded as 1,350.6 people per square mile (521.5/km2), with 45,819 housing units at an average density of 544.2 per square mile (210.1/km2). The 2000 racial makeup of the city was 60.8% White, 22.7% African American, 1.4% Asian, 0.5% Native American, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 12.4% from other races, and 2.3% from two or more races. About 23.6% of the population was Hispanic or Latino of any race. Non-Hispanic Whites were 45.8% of the population in 2010,[45] down from 66.6% in 1980.[46]

In 2000, the census recorded 42,279 households, of which 29.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.4% were married couples living together, 16.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.4% were not families. Around 31.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.9% had someone living alone at 65 years of age or older. The average household size was calculated as 2.49 and the average family size 3.19.

In 2000, 25.4% of the population was under the age of 18, 20.3% from 18 to 24, 25.0% from 25 to 44, 16.0% from 45 to 64, and 13.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 28 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $26,264, and for a family was $33,919. Males had a median income of $26,902 versus $21,159 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,584. About 26.3% of the population and 19.3% of families lived below the poverty line. Of the total population, 30.9% of those under the age of 18 and 13.0% of those 65 and older lived below the poverty line.

A 2020 census showed on a heat map that McLennan County displayed an estimated 1.3% of partnered households that are same-sex.[47]

Economy

editAccording to the Greater Waco Chamber of Commerce, the top employers in McLennan County are:[48][49]

| # | Employer | Employees 2015 | Employees 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baylor University | 2,675 | 3,253 |

| 2 | Ascension Providence | 2,397 | 3,075 |

| 3 | Waco Independent School District | 2,500 | 2,373 |

| 4 | H-E-B | 1,500 | 2,000 |

| 5 | Baylor Scott & White Health (Hillcrest) | 1,800 | 1,736 |

| 6 | Texas State Technical College | 1,706 | |

| 7 | Veterans Affairs | 1,682 | |

| 8 | City of Waco | 1,506 | 1,518 |

| 9 | Sanderson Farms, Inc. | 1,041 | 1,200 |

| 10 | Walmart | 1,656 | 1,174 |

| 11 | McLennan County | 1,157 | |

| 12 | Midway Independent School District | 1,067 | 1,081 |

| 13 | AbbVie | 785 | |

| 14 | L3 Technologies | 2,300 | 774 |

| 14 | McLennan Community College | 719 | |

| 15 | Mars Wrigley | 700 | |

| 16 | Aramark | 696 | |

| 17 | American Income Life | 693 | |

| 18 | Magnolia Network | 675 | |

| 19 | Texas Materials | 672 | |

| 20 | Cargill Value Added Meats | 646 | |

| 21 | Tractor Supply | 640 | |

| 22 | SpaceX | 590 |

Arts and culture

editLibraries and museums

editWaco is served by the Waco-McLennan County Library system.[50] The Armstrong Browning Library, on the campus of Baylor University, houses collections of English poets Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning.[51] The Red Men Museum and Library houses the archives of the Improved Order of Red Men.[52] The Lee Lockwood Library and Museum is home to the Waco Scottish Rite of Freemasonry.[53] The Waco Mammoth National Monument is a paleontological site and museum managed by the National Park Service in conjunction with the City of Waco and Baylor University.[54]

Other museums in Waco include the Dr Pepper Museum, Texas Sports Hall of Fame, Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Historic Waco [55]and the Mayborn Museum Complex.

Attractions

editNotable attractions in Waco include the Hawaiian Falls water park and the Grand Lodge of Texas, one of the largest Grand Lodges in the world.[56] The Waco Suspension Bridge is a single-span suspension bridge built in 1870, crossing the Brazos River.[57] Indian Spring Park marks the location of the origin of the town of Waco, where the Huaco Indians had settled on the bank of the river, at the location of an icy cold spring.[58] The Doris Miller Memorial is a public art installation along the banks of the Brazos River.[59] A nine-foot bronze statue of Miller was unveiled on December 7, 2017, temporarily located at nearby Bledsoe-Miller Park.[60]

Waco Mammoth National Monument is a partnership between the City of Waco, Baylor University, the Waco Mammoth Foundation and the National Park Service. The site contains the fossils of 24 Columbian mammoths and other animals, including a tortoise, a camel and a sabretooth tiger.

Downtown Waco is home to Magnolia Market, a shopping complex containing specialty stores, food trucks, and event space, set in repurposed grain silos originally built in 1950 for the Brazos Valley Cotton Oil Company.[61] The Magnolia Market, operated by Chip and Joanna Gaines of the HGTV TV series Fixer Upper, saw 1.2 million visitors in 2016.[62]

Sports

editThe Baylor Bears athletics teams compete in Waco. The football team has won or tied for nine conference titles, and have played in 24 bowl games, garnering a record of 13–11. The women's basketball team won the NCAA Division I women's basketball tournament in 2005, 2012 and 2019. The men's basketball team won the NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament in 2021.

The Waco BlueCats, an independent minor league baseball team, planned to play in the inaugural season of the Southwest League of Professional Baseball in 2019. A new ballpark was planned for the suburb of Bellmead.[63]

The American Basketball Association had a franchise for part of the 2006 season, the Waco Wranglers. The team played at Reicher Catholic High School and practiced at Texas State Technical College.

Previous professional sports franchises in Waco have proven unsuccessful. The Waco Marshals of the National Indoor Football League lasted less than two months amidst a midseason ownership change in 2004. (The team became the beleaguered Cincinnati Marshals the following year.) The Waco Wizards of the now-defunct Western Professional Hockey League fared better, lasting into a fourth season before folding in 2000. Both teams played at the Heart O' Texas Coliseum, one of Waco's largest entertainment and sports venues.

The Southern Indoor Football League announced that Waco was an expansion market for the 2010 season. It was rumored they would play in the Heart O' Texas Coliseum. However, the league broke up into three separate leagues, and subsequently, a team did not come to Waco in any of the new leagues.

Professional baseball first came to Waco in 1889 with the formation of the Waco Tigers, a member of the Texas League. The Tigers were renamed the Navigators in 1905, and later the Steers. In 1920, the team was sold to Wichita Falls. In 1923, a new franchise called the Indians was formed and became a member of the Class D level Texas Association. In 1925, Waco rejoined the Texas League with the formation of the Waco Cubs.

On June 20, 1930, the first night game in Texas League history was played at Katy Park in Waco. The lights were donated by Waco resident Charles Redding Turner, who owned a local farm team for recruits to the Chicago Cubs.

On the night of August 6, 1930, baseball history was made at Katy Park: in the eighth inning of a night game against Beaumont, Waco left fielder Gene Rye became the only player in the history of professional baseball to hit three home runs in one inning.

The last year Waco had a team in the Texas League was 1930, but fielded some strong semipro teams in the 1930s and early 1940s. During the World War II years of 1943–1945, the powerful Waco Army Air Field team was probably the best in the state; many major leaguers played for the team, and it was managed by big-league catcher Birdie Tebbetts.

In 1947, the Class B level Big State League was organized with Waco as a member called the Waco Dons.

In 1948, A.H. Kirksey, owner of Katy Park, persuaded the Pittsburgh Pirates club to take over the Waco operation, and the nickname was changed to Pirates. The Pirates vaulted into third place in 1948. They dropped a notch to fourth in 1949, but prevailed in the playoffs to win the league championship. The Pirates then tumbled into the second division, bottoming out with a dreadful 29–118, 0.197 club in 1952. This mark ranks as one of the 10 worst marks of any 20th-century full-season team. When the tornado struck in 1953, it destroyed the park. The team relocated to Longview to finish the season and finished a respectable third with a 77–68 record.

Waco has many golf clubs and courses, including Cottonwood Creek Golf Course.[64]

In 2018, Bicycle World Texas IronMan 70.3 Waco held its inaugural event in the city on October 26.[65]

Parks and recreation

editA seven-mile scenic riverwalk along the east and west banks of the Brazos River stretches from the Baylor campus to Cameron Park Zoo. This multiuse walking and jogging trail passes underneath the Waco Suspension Bridge and captures the peaceful charm of the river.[66] Lake Waco is a reservoir along the western border of the city.

Cameron Park is a 416-acre (168 ha) urban park featuring playgrounds, picnic areas, a cross-country running track, and a disc golf course.[67] In 2009, the US Department of the Interior designated the Cameron Park Trail System as a National Recreation Trail.[68] The park also contains Waco's 52-acre (21 ha) zoo, the Cameron Park Zoo.[68]

Government

editWaco has a council-manager form of government. Citizens are represented on the City Council by six elected members; five from single-member districts and a mayor who is elected at-large.[69] The city offers a full line of city services typical of an American city this size, including: police, fire, Waco Transit buses, electric utilities, water and wastewater, solid waste, and the Waco Convention and Visitors Bureau.

The Heart of Texas Council of Governments is headquartered in Waco on South New Road. This regional agency is a voluntary association of cities, counties, and special districts in the Central Texas area.

The Texas Tenth Court of Appeals is in the McLennan County Courthouse in Waco.[70]

The Waco Fire Department operates 13 fire stations throughout the city.[71]

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice operates the Waco Parole Office in Waco.[72]

The United States Postal Service operates the Waco Main Post Office along Texas State Highway 6.[73] In addition, it operates other post offices throughout Waco.

Politics

editThough the rest of McLennan County is deeply Republican, in statewide elections, Waco is a swing city. It voted for Republican Donald Trump in 2016, but flipped to Joe Biden in 2020.

| Election | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

| 2022 Governor | 53.0% | 45.5% |

| 2020 President | 48.0% | 50.0% |

| 2020 Senator | 50.2% | 46.4% |

| 2018 Governor | 52.7% | 45.7% |

| 2018 Senator | 47.5% | 51.7% |

| 2016 President | 47.6% | 46.6% |

Education

editWaco Independent School District serves most of the city of Waco. Portions of the city also lie in the boundaries of Midway Independent School District, Bosqueville ISD, China Spring ISD, Connally ISD, and La Vega ISD. Three large public high schools are in the Waco city limits: Waco High School (Waco ISD), University High School (Waco ISD), and Midway High School (Midway ISD). The schools are all rivals in sports, academics, and pride. Former high schools in Waco ISD were A.J. Moore High School, G.W. Carver High School, Richfield High School, Jefferson-Moore High School, and a magnet school known as A.J. Moore Academy.

Charter high schools in Waco include Harmony Science Academy, Methodist Children's Home, Premier High School of Waco, Rapoport Academy Public School, and Waco Charter School (EOAC). Local private and parochial schools include Live Oak Classical School, Parkview Christian Academy, Reicher Catholic High School, Texas Christian Academy, Vanguard College Preparatory School, and Waco Montessori School.

The three institutions of higher learning in Waco are:

In the past, several other higher education institutions were in Waco:[75]

- A&M College

- AddRan Male & Female College (relocated to Fort Worth, now Texas Christian University)

- The Catholic College

- Central Texas College (HBCU)

- The Gurley School

- The Independent Biblical and Industrial School

- Paul Quinn College (HBCU) (relocated to Dallas)

- Provident Sanatarium

- Toby's Practical Business College

- The Training School

- Waco Business College

Media

editThe major daily newspaper is the Waco Tribune-Herald. Other publications include The Waco Citizen, The Anchor News, The Baylor Lariat, Tiempo, Wacoan, and Waco Today Magazine.

The Waco television market (shared with the Killeen/Temple and Bryan/College Station areas) is the 89th-largest television market in the US and includes these stations:[76]

- KCEN 6 (NBC)

- KWTX 10 (CBS, Telemundo on DT2)

- KAMU 12 (PBS)

- KXXV 25 (ABC)

- KWKT 44 (Fox)

- KNCT 46 (CW)

- KAKW 62 (Univision)

The Waco radio market is the 190th-largest radio market in the US and includes:

- KRMX-FM 92.9 (Country)

- KWBT-FM 94.5 (Urban adult contemporary)

- KBGO-FM 95.7 (Classic Hits)

- KBGO-FM 95.7 HD-2 (Rhythmic Top-40) (Z-95.1)

- KWRA-FM 96.7 (Spanish Religious)

- KWTX-FM 97.5 (Pop)

- WACO-FM 99.9 (Country)

- KXZY-FM 100.7 (Spanish religious)

- KBRQ-FM 102.5 (Rock)

- KWBU-FM 103.3 (NPR)

- KWOW-FM 104.1 (Spanish)

- KBHT-FM 104.9 (Variety Hits)

- KIXT-FM 106.7 (Classic Rock)

- KWPW-FM 107.9 (Pop)

- KBBW-AM 1010 / FM 105.9 (Religious/Talk Radio)

- KWTX-AM 1230 (News talk)

- KRZI-AM 1660 / FM 92.3 (ESPN)

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editInterstate 35 is the major north–south highway serving Waco. It directly connects the city with Dallas (I-35E), Fort Worth (I-35W), Austin, and San Antonio. Texas State Highway 6 runs northwest–southeast and connects Waco to Bryan/College Station and Houston. US Highway 84 is the major east–west thoroughfare in the area. It is also known as Waco Drive, Bellmead Drive (as it passes through the city of Bellmead), Woodway Drive or the George W. Bush Parkway. Loop 340 bypasses the city to the east and south. State Highway 31 splits off US 84 just east of Waco and connects the city to Tyler, Longview, and Shreveport, Louisiana.

The first traffic circle in Texas was constructed in Waco in 1933 at the intersections of US 81 and US 77.[77] It was later expanded to include intersections with Valley Mills Dr. and La Salle Ave. Drivers were confused and upset by the circle when it was first constructed, which even led to lawsuits. In 2013 a lone star was added to the center of the circle. Lane markings and new signage were added in 2018 to improve traffic flow and to help guide drivers.[78]

The Waco area is home to three airports. Waco Regional Airport (ACT) serves the city with daily flights to Dallas/Fort Worth International via American Eagle. TSTC Waco Airport (CNW) is the site of the former James Connally AFB and was the primary fly-in point for former President George W. Bush when he was visiting his ranch in Crawford. It also serves as a hub airport for L3 and several other aviation companies. McGregor Executive Airport (PWG) is a general-aviation facility west of Waco.

Local transportation is provided by the Waco Transit System, which offers bus service Monday–Saturday to most of the city. Nearby passenger train service is offered via Amtrak. The Texas Eagle route includes daily stops in McGregor, 20 miles west of the city.

Notable people

editSports

edit- Lee Ballanfant, born in Waco, was a Major League Baseball umpire

- Kwame Cavil, born in Waco, is a Canadian Football League wide receiver for the Edmonton Eskimos[79]

- Perrish Cox, former NFL cornerback for the Tennessee Titans, was born in Waco, grew up in Waco, and went to University High School[80]

- Zach Duke, graduated from Midway High School in Waco, is a former major league baseball pitcher for nine teams between 2005 and 2019

- Dave Eichelberger, born in Waco, is a professional golfer who has won several tournaments on the PGA Tour and Champions Tour levels[81]

- Casey Fossum, graduated from Midway High School in Waco, pitched in Major League Baseball player for five different teams over nine seasons[82]

- Ken Grandberry, born in Waco, is a former NFL running back for the Chicago Bears[83]

- Rufus Granderson, born in Waco, is a former AFL defensive tackle for the Dallas Texans[84]

- Ty Harrington is the head coach for the Texas State University baseball team. He was born in Waco and attended Midway High School[85]

- Andy Hawkins, born in Waco, is a former MLB pitcher[86]

- Sherrill Headrick, born in Waco, came to the American Football League's Dallas Texans as an undrafted linebacker[87]

- Dwight Johnson, born and raised in Waco, was an NFL Defensive lineman for the Philadelphia Eagles and the New York Giants

- Derrick Johnson, born and raised in Waco, was an NFL Linebacker for the Kansas City Chiefs

- Michael Johnson, United States sprinter; graduated from Baylor University in 1990[88]

- Jim Jones, born in Waco, American football player[89]

- Rob Powell, fitness coach who has two certificates of Guinness World Records

- Dominic Rhodes, born in Waco, is a professional football running back who played for the Virginia Destroyers of the United Football League[90]

- John Richards, born in Waco, is a former racing driver and motorcycle racer

- Bill Rogers, born in Waco, is a professional golfer who won the 1981 Open Championship and was voted 1981 PGA Tour Player of the Year

- LaDainian Tomlinson is a former NFL football player for the New York Jets and San Diego Chargers; born in Rosebud, he grew up in Waco, and went to University High School[91]

- D. L. Wilson, born in Waco, is an American professional stock car racing driver

Former pro baseball players from Waco

edit- Kevin Belcher August 8, 1967, CF-RF MLB 1990–1990[92]

- Lance Berkman October 2, 1976, LF-RF MLB 1999–2011[93]

- Andy Cooper April 24, 1898 P NLB 1920–1939[94]

- Buzz Dozier August 31, 1927, P MLB 1947–1949[95]

- Louis Drucke March 12, 1888, P MLB 1909–1912[96]

- Boob Fowler November 11, 1900, SS MLB 1923–1926[97]

- Charlie Gorin June 2, 1928, P MLB 1954–1955[98]

- Donald Harris December 11, 1967, CF-RF MLB 1991–1993[99]

- Al Jackson December 25, 1935, P MLB 1959–1969[100]

- Scott Jordan May 27, 1963, CF MLB 1988–1988[101]

- Rudy Law July 10, 1956, OF MLB 1978–1986[102]

- Dutch Meyer June 10, 1915, 2B MLB 1940–1946[citation needed]

- Arthur Rhodes October 24, 1969, P MLB 1991–2011[103]

- Schoolboy Rowe November 1, 1910, P MLB 1933–1949[104]

- Ted Wilborn December 16, 1958, OF MLB 1979–1980[105]

Movies and television

edit- Jules Bledsoe, stage and screen actor and singer. When the Broadway premiere of Show Boat was delayed in 1927 by Ziegfeld, Paul Robeson became unavailable, so Bledsoe stepped in. He played and sang the role of Joe, introducing "Ol' Man River"[106]

- Shannon Elizabeth, actress of American Pie fame, was born in Houston and grew up in Waco[107]

- Chip and Joanna Gaines, Waco area home renovators and remodelers came to national attention with their TV show Fixer Upper. They have since expanded into a variety of local developments, including Magnolia Market, Hotel 1928 and are a major tourism draw for the Waco area

- Peri Gilpin, actress, best known for her television character Roz Doyle on the series Frasier, was born in Waco and raised in Dallas[108]

- Texas Guinan, Hollywood actress from 1917 to 1933. She was active in vaudeville and theater, and was in many movies (often as the gun-toting hero in silent westerns, more than a match for any man). She also had a successful career as a hostess in nightclubs and speakeasies in New York City[109]

- Anne Gwynne, Hollywood actress who starred in a number of films of the 1940s; she was born in Waco

- Thomas Harris, author of The Silence of the Lambs, was a student at Baylor University, and covered the police beat for the Waco Tribune-Herald[110]

- Jennifer Love Hewitt, actress, was born in Waco[111]

- Terrence Malick, director of The Thin Red Line, was raised in Waco. He also directed The Tree of Life, which was set in the town of Waco in the 1950s[112]

- Steve Martin, comedian, actor, author and musician, was born in Waco[113]

- Kevin Reynolds, director (Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, The Count of Monte Cristo, Waterworld), born and raised in Waco[114]

Music

edit- Wade Bowen, Texas country artist and former lead singer of Wade Bowen and West 84, was born and raised in Waco[115]

- David Crowder Band (1996–2012), a Christian worship band, is from Waco[116]

- Johnny Gimble, two time Grammy Award winning pioneer in Texas Swing and country music * Pat Green, country music singer-songwriter, was raised in Waco[117]

- Roy Hargrove, a Grammy Award-winning jazz trumpeter, born and raised in Waco[118]

- Kari Jobe, a two-time Dove Award-winning Christian singer-songwriter was born in Waco[119]

- Willie Nelson, country music singer-songwriter, born in nearby Abbott[120]

- Ted Nugent, guitarist, along with his wife Shemane and son Rocco Nugent, live in Waco[121] He filmed his VH1 show Surviving Nugent on his ranch in nearby China Spring.

- Domingo Ortiz, percussionist for the band Widespread Panic, grew up in Waco[122]

- Bill Payne, keyboardist for the rock band Little Feat, was born and raised in the Waco area[123]

- Billy Joe Shaver, Country songwriter ("Honky Tonk Heroes") and singer ("Old Chunk of Coal")[124]

- Ashlee Simpson, pop music singer, was born in Waco[125]

- Jessica Simpson, pop music singer, was born in Abilene and raised in Waco

- Strange Fruit Project, an underground hip hop trio, is from Waco[126]

- Hank Thompson, was born in Waco inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame and Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame[127]

- Holly Tucker was born in Waco[128][129][130]

- Mercy Dee Walton was born in Waco[131]

- Tom Wilson, record producer, grew up in Waco

- Forrest Frank, a two-time Dove Award - winning Christian artist was born and raised in Waco.

Politics

edit- Kip Averitt, State senator from District 22 from 2002 to 2010,[132] and State Representative from District 56 from 1994 to 2002, and currently is a lobbyist

- Joe Barton, former US congressman representing Texas's 6th congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1985 to 2019, was born and reared in Waco[133]

- Leon Jaworski, who prosecuted Nazi war criminals during the Nuremberg trials and then was the special prosecutor who brought down the Nixon administration during the Watergate scandal, was born and raised in Waco

- Charles R. Matthews, former mayor of Garland, Texas, member of the Texas Railroad Commission, and chancellor of the Texas State University System, is a Waco native[134]

- Lyndon Lowell Olson Jr., former U.S. Ambassador to Sweden under President Bill Clinton, was born and raised in Waco

- William R. Poage, US Congressman who represented Texas's 11th congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1937 to 1978, was born in Waco

- Ann Richards, former governor of Texas and keynote speaker at the 1988 Democratic National Convention, was born in the Waco suburb of Lacy Lakeview and graduated from Baylor University[135]

- Pete Sessions, US congressman who represented Texas's 32nd and 5th congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1997 to 2019, was born and raised in Waco

- Ralph Sheffield, member of the Texas House of Representatives from Bell County and restaurateur in Temple, was born in Waco in 1955[136]

- David McAdams Sibley Sr., former state senator (1991–2002), was mayor of Waco (1987–1988)[137]

Other

edit- Shawn Achor, born in Waco, is a best-selling author of The Happiness Advantage. He was featured on Oprah Winfrey's Super Soul Sunday. He also co-authored a best-selling children's book with his sister Amy Blankson called How to Make a Shark Smile.

- T. Berry Brazelton, born in Waco, was a pediatrician and author. He developed the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale

- Tony Castro, bestselling author of several books and syndicated columnist, was born in Waco. He graduated from Baylor University and was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard

- Brigham Paul Doane, born in Waco, is a professional wrestler. Under the ring name "Masada", Doane achieved international recognition in the Hardcore wrestling scene

- Hallie Earle (1880–1963) was the first licensed female physician in Waco, a 1902 M.S. from Baylor, and the only female graduate of 1907 Baylor University Medical School in Dallas

- Frank Shelby Groner (1877–1943) pastor of Columbus Avenue Baptist Church

- Heloise, of the "Hints from Heloise" column, was born in Waco. Her column addresses lifestyle hints, including consumer issues, pets, travel, food, home improvement, health, and much more

- Allene Jeanes (1906–1995), a chemical engineer whose work included the development of Dextran and Xanthan gum, was born in Waco and received her bachelor's degree from Baylor University in 1928

- Reh Jones, born in Waco, American YouTube personality, owner, producer

- David Koresh, leader of the Branch Davidians, died along with 75 others in the blaze during the Waco siege

- Robert L. Leuschner Jr. was born in Waco. He attended Rice University, followed a career in the U.S. Navy and retired as a Rear Admiral

- Vivienne Malone-Mayes, Waco-born mathematician, the first African-American faculty member of Baylor University who developed novel methods of teaching mathematics

- Robert W. McCollum (1925–2010), virologist who made important discoveries regarding polio and hepatitis[138]

- Glenn McGee, born in Waco, is a bioethicist, syndicated columnist[139] for Hearst Newspapers and for The Scientist and scholar.

- Doris (Dorie) Miller, born in Waco, was an African American cook in the United States Navy and a hero during the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He was the first African American to be awarded the Navy's second-highest honor, the Navy Cross. Portrayed in the 2001 movie Pearl Harbor

- C. Wright Mills, born in Waco, was a sociologist. Among other topics, he was concerned with the responsibilities of intellectuals in post-World War II society, and advocated relevance and engagement over disinterested academic observation

- Mark W. Muesse, born in Waco, is a philosopher and author

- William R. Munroe, born in Waco, vice admiral in the U.S. Navy, Commander-in-Chief, United States Fourth Fleet during World War II

- Felix Huston Robertson, born in Washington-on-the-Brazos, was a former Confederate Civil War general who became a wealthy lawyer, railroad director, and land speculator in Waco during Reconstruction

- Ford O. Rogers, born in Waco, major general in the United States Marine Corps during World War II, recipient of the Navy Cross

- Fred I. Stalkup, chemical engineer, graduated from Rice University and became a recognized expert in enhanced oil recovery

- John Willingham, a writer and historian born in Waco, served as McLennan County elections administrator from 1984 through 1992[140]

- Robert Wilson, born in Waco, is a stage director

- Ben Christie, better known online as Uncle Ben, the owner of the Urban Rescue Ranch[1]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ "How Many of These Texas City Nicknames Do You Know?". Texas Standard. July 29, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Waco, Texas

- ^ Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places of 50,000 or More, Ranked by July 1, 2023 Population: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023 (SUB-IP-EST2023-ANNRNK) Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division Release Date: May 2023

- ^ "List of 2020 Census Urban Areas". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product: All Industries in McLennan County, TX". Federal Reserve Economic Data. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "QuickFacts : Waco city, Texas". Census.gov. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ^ Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places of 50,000 or More, Ranked by July 1, 2022 Population: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023 (SUB-IP-EST2023-ANNRNK) Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division Release Date: May 2024

- ^ American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau Archived June 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ Annual and Cumulative Estimates of Resident Population Change for Metropolitan Statistical Areas in the United States and Puerto Rico and Metropolitan Statistical Area Rankings: April 1, 2020, to July 1, 2023 (CBSA-MET-EST2023-CHG)

- ^ "Thomas M. Duke to Stephen F. Austin, 06-xx-1824". Digital Austin Papers. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ Clark, Longwell, Evelyn (June 15, 2010). "McClennan, Neil". www.tshaonline.org.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Natalie, Ornish (June 12, 2010). "De Cordova, Jacob Raphael". www.tshaonline.org.

- ^ Erath, Lucy (1923). The Memoirs of Major George B. Erath. Austin, Texas: Texas State Historical Association.

- ^ Kelley, Dayton (1966). Waco, & McLennan County, Texas: 1876. Waco, Texas: Texian Press. p. 12.

- ^ Davis, Joe Tom (1989). Legendary Texians, Vol. 4. Austin, Texas: Eakin Press. p. 151. ISBN 0890156697.

- ^ Roger, Conger (1992). The Waco Suspension Bridge. Friends of the Texas Ranger Library. p. 224.

- ^ "St. Louis Southwestern Railway, "The Cotton Belt Route"". American-Rails, June 12, 2023. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ "Texas and St. Louis Railway". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ "Gatesville, TX". Texas State Historical Society. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ "St. Louis Southwestern Railroad History". Arkansas Railroad Museum. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ Perez, Samara (April 13, 2020). "Made in Texas: The man who created Dr Pepper wanted his drink to smell like a drug store he liked". KPRC. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Waters, Rick (March 1, 2010). "A fateful fire". TCU Magazine. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Strouse, Dalton; Sawyer, Amanda. "Greenwood Cemetery". Waco History. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "The Deadly Crashat Crush". Texas Co-op Power Magazine. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Minutaglio, Bill (2021). A Single Star and Bloody Knuckles: A History of Politics and Race in Texas. University of Texas Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1477310366.

- ^ Lichtenstein, Andrew; Lichtenstein, Alex (2017). Marked Unmarked Remembered. A Geography of American Memory. West Virginia University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-1943665891.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Patricia (2005). The First Waco Horror. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. pp. 185–91.

- ^ "Suspect Killed; Waco mob burns body". The Dallas Express. Dallas, Houston, Texas: W.E. King. June 3, 1922. pp. 1–8. ISSN 2331-334X. OCLC 9839625. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Pohlen, Jerome (2006). Oddball Texas: A Guide to Some Really Strange Places. Chicago Review Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-1569764725.

- ^ "Top Ten US Killer Tornadoes". Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ^ "Twister Memorial to be Displayed". The Victoria Advocate. June 27, 2004.

- ^ "The Waco tragedy, explained". April 19, 2018.

- ^ "9 Dead, 192 Charged in Waco Biker Gang Shooting". May 17, 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ "History of the ALICO Building". ALICO Building. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Waco RGNL AP, TX". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Dallas". National Weather Service. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Waco city, Texas". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Waco city, Texas". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Waco city, Texas". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Waco (city), Texas". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ "Texas – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. census and other surveys likely undercount the number of LGBTQ+ people living in Texas". data.census.gov. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ "Customized Report". wacochamber.com.

- ^ "Top 2023 Waco Employers". January 7, 2022.

- ^ "Waco-McLellan County Library". City of Waco, Texas. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ "Armstrong Browning Library". Waco Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ Masters, Claire (April 2014). "Portals to the past: Red Men plate exhibit at Waco library". Waco Today Magazine. Waco Tribune-Herald. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ "Lee Lockwood Library and Museum – Waco's Best Kept Secret". www.srftx.org.

- ^ Office of the Press Secretary (July 10, 2015). "President Obama Designates New National Monuments". whitehouse.gov – via National Archives.

- ^ "Historic Waco". Historic Waco. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ "Masonic Membership Statistics". www.msana.com. Archived from the original on November 6, 2006.

- ^ "Historic Bridge Foundation". Historic Bridge Foundation. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ "Waco History". Wacocvb.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ "Doris Miller Memorial". dorismillermemorial.org. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ Smith, J. B. (December 7, 2017). "Pearl Harbor Hero". Waco Tribune-Herald. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ "Brazos Valley Cotton Oil Mill | Waco History". Waco History. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ J.B. Smith. "Tourism boom of 2016 puts Waco on map of travel destinations". WacoTrib.com. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ^ "New for 2018: Waco BlueCats". Ballpark Digest. August Publications. November 30, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2022.

- ^ "Cottonwood Creek Golf Course". waco-texas.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ "IronMan 70.3 Waco". ironman.co. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ "Suspension Bridge & Riverwalk – Parks & Recreation – City of Waco, Texas". waco-texas.com.

- ^ Ryan, Terri (May 2010). "The man behind Cameron Park". WacoTrib. Waco Tribune-Herald. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ a b "Cameron Park Trails". www.nrtapplication.org. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "City Council – City of Waco, Texas". waco-texas.com.

- ^ "Contact Information." Texas Tenth Court of Appeals. Retrieved on March 10, 2010.

- ^ "Waco Fire Stations". waco-texas.com. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ "Directory – Region and District Parole Offices". Texas Department of Criminal Justice. May 28, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ "Find Locations: Waco". United States Postal Service. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ "TX 2022 Congressional". Dave's Redistricting. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ "The Waco Horror" (PDF). The Crisis. June 1916. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ "Local Television Market Universe Estimates" (PDF). The Nielsen Company. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 17, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ Luna, Melinda. "The Waco Traffic Circle: An Early Texas Roundabout". ASCE. Archived from the original on December 1, 2023. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ "Waco: Traffic circle sees improvements for drivers". KWTX. May 30, 2018. Archived from the original on June 2, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ "Kwame Cavil". Pro-Football Reference.com. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Perrish Cox". Pro-Football Reference.com. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Dave Eichelberger". pgatour.com. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Casey Fossum". BaseballReference.com. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Ken Grandberry". Pro-Football Reference.com. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Rufus Granderson". profootballarchives.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Ty Harrington – Baseball Coach". Texas State Athletics. Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- ^ "Andy Hawkins". BaseballReference.com. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Sherrill Headrick". Pro-Football Reference.com. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Michael Johnson". baylorbears.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Jim Jones". pro-football-reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

- ^ "Dominic Rhodes". Pro-Football Reference.com. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "LaDainian Tomlinson". gamedayr.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ "Kevin Belcher". BaseballReference.com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Lance Berkman". BaseballReference.com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Andy Cooper". Baseball Reference.Com. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ "Buzz Dozier". BaseballReference.com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Louis Drucke". BaseballReference.com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Boob Fowler". BaseballReference.com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Charlie Gorin". Baseball Reference.Com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Donald Harris". Baseball Reference.Com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Al Jackson". Baseball Reference.Com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Scott Jordan". Baseball Reference.Com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Rudy Law". Baseball Reference.Com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Arthur Rhodes". Baseball Reference.Com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Schoolboy Rowe". Baseball Reference.Com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Ted Wilborn". Baseball Reference.Com. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Geary, Lynnette. "Jules Bledsoe's voice still rings". Waco History Project. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Shannon Elizabeth". IMDb. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Peri Gilpin". IMDb. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Texas Guinan". IMDb. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Thomas Harris". IMDb. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Jennifer Love Hewitt". IMDb. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Terrence Malick". Answers Corporation facebook. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Steve Martin". IMDb. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "Kevin Reynolds". IMDb. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Hoover, Carl (May 30, 2013). "Smaller Wade Bowen Classic brings stars to help West". Waco Tribune-Herald. Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "David Crowder Band". Baylor® University. December 13, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "Pat Green". Scripps Interactive Newspapers Group. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "Roy Hargrove". The Dallas Morning News Inc. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "Kari Jobe". Athens Publishing. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "Willie Nelson". BeenVerified. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "Ted Nugent". WorldNow and KCEN. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ Rossiter, Erin. "Ortiz: 'I've been blessed'". Online Athens. Athens Banner-Herald. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ "Bill Payne of Little Feat". Highline Ballroom. Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ "Billy Joe Shaver". Waco Tribune Herald. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ "Ashlee Simpson". IMDb. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ "Strange Fruit Project". The Dallas Morning News Inc. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ "Hank Thompson". Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ "Holly Tucker". AllMusic. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ Staff (August 15, 2017). "Waco: Holly Tucker nominated for 2 TCMA Awards". KWTX.

- ^ Melson, Kayla (September 9, 2017). "'The Voice' contestant Holly Tucker visits NC9". elpasoproud.com.

- ^ "Mercy Dee Walton". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ "Kip Averitt". Vote Smart.com. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "Joe Barton". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Texas, Railroad Commission of. "Railroad Commission of Texas: An Inventory of Railroad Commission Commissioners Records at the Texas State Archives, 1898–1901, 1906–1908, 1916, 1920–1967, 1978–1980, 1997–2005, undated, bulk about 1930 – about 1960". legacy.lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ "Ann Richards". tsl.state.tx.us. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "Ralph Sheffield Biography" (PDF). Legislative Reference Library. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ "David Sibley" (PDF). waco-texas.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 3, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis. "Robert W. McCollum, Dean of Dartmouth Medical School, Dies at 85", The New York Times, September 25, 2010. Accessed September 26, 2010.

- ^ "Glenn McGee". Times Union. Archived from the original on August 29, 2006. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ Smith, J.B. (March 16, 2011). "Former McLennan Elections Official John Willingham to Sign Copies of His Book". Waco Tribune-Herald. BH Media Group. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

Bibliography

editExternal links

edit- Official website

- Waco, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Waco History Project