The Warlord Era was the period in the history of the Republic of China between 1916 and 1928, when control of the country was divided between military cliques of the Beiyang Army and other regional factions. The era began after the death of Yuan Shikai, the de facto dictator of China after the Xinhai Revolution had overthrown the Qing dynasty and established the Republic of China in 1912. Yuan's death on 6 June 1916 created a power vacuum which was filled by warlordism and widespread violence, chaos, and oppression. The Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) government of Sun Yat-sen, based in Guangzhou, began to contest Yuan's Beiyang government based in Beijing for recognition as the legitimate government of China.

| Warlord Era | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

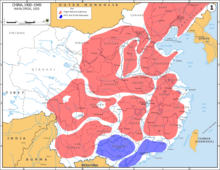

Major Chinese warlord coalitions in 1925. The blue area was controlled by the Kuomintang, which later formed the Nationalist government in Guangzhou. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 軍閥時代 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 军阀时代 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The most powerful cliques were the Zhili clique led by Feng Guozhang, who controlled several northern provinces; the Anhui clique led by Duan Qirui, based in several southeastern provinces; and the Fengtian clique led by Zhang Zuolin, based in Manchuria. The three cliques often engaged in war for expansion of their territories and for hegemony. In mid-1917, after Yuan's successor Li Yuanhong attempted to remove Duan as premier, the general Zhang Xun forced Li to resign and made a brief attempt to restore the Qing dynasty, which was quashed by Duan's troops. Feng became acting president, but was forced to step down by Duan in late 1918 and was replaced by Xu Shichang. In mid-1920, the new Zhili leader, Cao Kun, defeated Duan in the Zhili–Anhui War, in an alliance with Zhang. A power struggle broke out between Cao and Zhang, which ended with Cao's victory in the First Zhili–Fengtian War in 1922. Cao became president until 1924, when during the Second Zhili–Fengtian War he was betrayed by his subordinate Feng Yuxiang, who joined with Zhang to stage a coup against Cao. They shared power and brought back Duan to serve as president before Zhang removed them both in 1926; Zhang then led the Beiyang government until 1928.

The warlords of southern China, who had cooperated against Yuan's dictatorship and then Duan's attempt to extend Beiyang control to the south, were divided between the Yunnan, Guangxi, Guizhou, and Sichuan cliques.[1][2] Sun Yat-sen created an alternative government based in Guangzhou to oppose the Beiyang warlords, but Lu Rongting's Guangxi clique rivaled him for control, leading Sun to abandon it in 1918. In 1920, the warlord Chen Jiongming invaded Guangdong and ended Lu's control in the Guangdong–Guangxi War, after which Sun returned. Chen soon turned on Sun over disagreements on strategy, after which the Yunnan warlord Tang Jiyao helped Sun regain power in 1923. To resolve the problem of being dependent on warlords, Sun accepted Soviet assistance in building a party and military infrastructure of his own, creating the Whampoa Military Academy and the National Revolutionary Army (NRA). After Sun died in 1925, the head of the Whampoa Academy, Chiang Kai-shek, emerged as the military leader of the NRA.[3] In 1926, he launched the Northern Expedition, which destroyed the troops of the Zhili and Anhui cliques. On 29 December 1928, Fengtian clique leader Zhang Xueliang retreated from Beijing and accepted the leadership of Chiang's Nationalist government, thus reunifying China and beginning the Nanjing decade.

Despite the official end of the Warlord Era in 1928, several continued to maintain their influence throughout the 1930s and 1940s, resulting in events such as the Central Plains War of 1929–1930, in which warlords Yan Xishan, Feng Yuxiang, and Li Zongren rebelled against Chiang. Continued control by former warlords over their regions was problematic for the Nanjing government during the Second Sino-Japanese War and Chinese Civil War. Other major warlords included Ma Hongkui and Ma Bufang in the far west; Liu Xiang and Liu Wenhui in Sichuan; Long Yun in Yunnan; Han Fuju in Shandong; and Sheng Shicai in Xinjiang.

Terminology

editDuring the New Culture Movement, Chen Duxiu introduced the term Junfa (軍閥), taken from the Japanese gunbatsu. It was not widely used until the 1920s, when it was taken up by left-wing groups to excoriate local militarists.[4] Previously, these militarist leaders were known as a Tuchun (督軍), or provincial military governor, owing to the system Yuan Shikai introduced after his centralization of power.

Origins

editThe origins of the armies and leaders which dominated politics after 1912 lay in the military reforms of the late Qing dynasty. During the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), the Qing dynasty was forced to allow provincial governors to raise their own armies, the Yong Ying, to fight against the Taiping rebels; many of these provincial forces were not disbanded after the Taiping rebellion was over, like Li Hongzhang's Huai Army.[5]

Strong bonds, family ties, and respectful treatment of troops were emphasized.[6] The officers were never rotated, and the soldiers were hand-picked by their commanders, and commanders by their generals, so personal bonds of loyalty formed between local officers and the troops, unlike Green Standard and Banner forces.[7] The late Qing reforms did not establish a national army; instead, they mobilized regional armies and militias that had neither standardization nor consistency. Officers were loyal to their immediate superiors and formed cliques based upon their place of origins and background. Units were composed of men from the same province. This policy was meant to reduce dialectal miscommunication, but had the side effect of encouraging regionalist tendencies.

Although the post–Taiping Rebellion governors are generally not recognized as the direct predecessors of the warlords, their combined military-civil authority and somewhat greater powers as compared to earlier governors provided a model for Republic-era provincial leaders. The fragmentation of military power due to the late Qing's lack of a unified military force, exacerbated by the rise of provincialism during the revolution, was also a strong factor behind the proliferation of warlords. Apart from administrative and financial obstacles, the late Qing government seemed to have relied on this divided military structure to maintain political control.[8]

The rising necessity of military professionalism, with scholars becoming heavily militarized, led to many officers from non-scholarly backgrounds rising to high command and even high office in civil bureaucracy. At this time, the military upstaged the civil service.[9] The influence of German and Japanese ideas of military predominance over the nation, coupled with the absence of national unity amongst the various cliques in the officer class, led to the fragmentation of power.[10]

The most powerful regional army was the northern-based Beiyang Army under Yuan Shikai, which received the best in training and modern weaponry.[11] The Xinhai Revolution in 1911 brought widespread mutiny across southern China. The revolution began with the Wuchang Uprising in October 1911, where soldiers began to mutiny and defect to a political opposition. These revolutionary forces established a provisional government in Nanjing the following year under Sun Yat-sen, who had returned from his long exile to lead the revolution. It became clear that the revolutionaries were not strong enough to defeat the Beiyang army and continued fighting would almost certainly lead to defeat. Instead, Sun negotiated with Beiyang commander Yuan Shikai to bring an end to the Qing and reunify China. In return, Sun would hand over his presidency and recommend Yuan to be the president of the new republic. Yuan refused to move to Nanjing and insisted on maintaining the capital in Beijing, where his power base was secure.

Reacting to Yuan's growing authoritarianism, the southern provinces rebelled in 1913 but were effectively crushed by Beiyang forces. Civil governors were replaced by military ones. In December 1915, Yuan stated his intention to become emperor of China at the head of a new dynasty. The southern provinces rebelled again in the National Protection War; but this time the situation was far more serious because most Beiyang commanders refused to recognize the monarchy. Yuan renounced his plans for restoring the monarchy to woo back his lieutenants; however, by the time of his death in June 1916, China had fractured politically. The North-South split would persist throughout the entire Warlord Era.

Yuan Shikai cut back on many government institutions in the beginning of 1914 by suspending parliament, followed by the provincial assemblies. His cabinet soon resigned, effectively making Yuan dictator of China.[12] After Yuan Shikai curtailed many basic freedoms, the country quickly spiraled into chaos and entered a period of warlordism. "Warlordism did not substitute military force for the other elements of government; it merely balanced them differently. This shift in balance came partly from the disintegration of the sanctions and values of China's traditional civil government."[13] During this period, there was a general shift from a state-dominated civil bureaucracy held by a central authority to a military-dominated culture held by many groups, with power shifting from warlord to warlord. A theme identified by C. Martin Wilbur was "that a great majority of regional militarists were 'static', that is to say that their principal aim was to secure and maintain control of a particular tract of territory."[14]

Warlords, in the words of American political scientist Lucian Pye, were "instinctively suspicious, quick to suspect that their interests might be threatened, hard-headed, devoted to the short run and impervious to idealistic abstractions".[15] Warlords usually came from strict military background, and were brutal in their treatment toward both their soldiers and the general population. In 1921, the North China Daily News reported that in Shaanxi, robbery and violent crimes were prevalent and frightened the farmers. Wu Peifu of the Zhili clique was known for suppressing strikes by railroad workers by terrorizing them with execution. A British diplomat in Sichuan witnessed two mutineers being publicly hacked to death with their hearts and livers hung out; another two being publicly burned to death; while others had slits cut into their bodies into which were inserted burning candles before they were hacked to pieces.[16]

Warlords placed great stress on personal loyalty, yet subordinate officers often betrayed their commanders in exchange for bribes known as "silver bullets", and warlords often betrayed allies. Promotion had little to do with competence, and instead warlords attempted to create an interlocking network of familial, institutional, regional, and master-pupil relationships together with membership in sworn brotherhoods and secret societies. Subordinates who betrayed their commanders could suffer harshly. In November 1925, Guo Songling, the leading general loyal to Marshal Zhang Zuolin—the "Old Marshal" of Manchuria—made a deal with Feng Yuxiang to revolt, which nearly toppled the "Old Marshal", who had to promise his rebel soldiers a pay increase; that, together with signs that the Japanese still supported Zhang, caused them to go back on their loyalty to him. Guo and his wife were both publicly shot and their bodies left to hang for three days in a marketplace in Mukden. After Feng betrayed his ally Wu to seize Beijing for himself, Wu complained that China was "a country without a system; anarchy and treason prevail everywhere. Betraying one's leader has become as natural as eating one's breakfast".[17]

"Alignment politics" prevented any one warlord from dominating the system. When one warlord started to become too powerful, the rest would ally to stop him, then turn on each other. The level of violence in the first years was restrained, as no leader wanted to engage in too much serious fighting. War brought the risk of damage to one's own forces. For example, when Wu Peifu defeated the army of Zhang Zuolin, he provided two trains to take his defeated enemies home, knowing that if in the future Zhang were to defeat him, he could count on the same courtesy. Furthermore, warlords did not have the economic or logistical capabilities required to achieve decisive victories, and were generally concerned instead with taking over smaller pieces of territory. The violence increased in intense as the 1920s went on, with the object being to damage the enemy and improve one's bargaining power within the "alignment politics".[18]

As the infrastructure in China was very poor, control of the railway lines and rolling stock were crucial in maintaining a sphere of influence. Railroads were the fastest and cheapest way of moving large number of troops, and most battles during this era were fought within a short distance of railways. Armoured trains, full of machine guns and artillery, offered fire support for troops going into battle. In 1925–1927, the largest detachment of armored trains, numbering 7 units, was in the service of Marshal Zhang Zongchang. The armored trains were built according to the World War I model by Russian designers who arrived from Harbin to Jinan, where they had railway workshops.[19] The constant fighting around the railroads caused much economic harm. In 1925, at least 50% of the locomotives being used on the line connecting Nanjing and Shanghai had been destroyed, with the soldiers of one warlord using 300 freight cars as sleeping quarters, all inconveniently parked directly on the rail line. To hinder pursuit, defeated troops tore up the railroads as they retreated; in 1924, damages amounted to 100 million Mexican silver dollars (the main currency used in China at the time). Between 1925 and 1927, fighting in eastern and southern China caused non-military railroad traffic to decline by 25%, raising the prices of goods and causing inventory to build up at warehouses.[20]

China's disunity during this period resulted in varied political experiments in different regions. Some regions experimented with aspects of democracy, including different mechanisms for election of city and provincial council elections. In Hunan, for example, a constitution and universal suffrage was established, and several levels of council were elected by popular vote. These experiments with partial democracy were not long-lasting.[21]: 66

Warlord profiles

editFew of the warlords had any sort of ideology. Yan Xishan, the "Model Governor" of Shanxi, professed a syncretic creed that merged elements of democracy, militarism, individualism, capitalism, socialism, communism, imperialism, universalism, anarchism, and Confucian paternalism into one. A friend described Yan as "a dark-skinned, mustached man of medium height who rarely laughed and maintained an attitude of great reserve; Yan never showed his inner feelings." He kept Shanxi on a different railroad gauge from the rest of China to make it difficult to invade his province, though that tactic also hindered the export of coal and iron, the main source of Shanxi's wealth. Feng Yuxiang, the "Christian General", promoted Methodism together with a vague sort of left-leaning Chinese nationalism, which led the Soviets to support him for a time. He banned alcohol, lived simply and wore the common uniform of an infantryman to show his concern for his men.[22]

Wu Peifu, the "Philosopher General", was a mandarin who passed the Imperial Civil Service exam, billing himself as the protector of Confucian values, usually appearing in photographs with the scholar's brush in his hand (the scholar's brush is a symbol of Confucian culture). Doubters noted, however, that the quality of Wu's calligraphy markedly declined when his secretary died. Wu liked to appear in photos taken in his office with a portrait of his hero George Washington in the background to reflect the supposed democratic militarism he was attempting to bring to China. Wu was famous for his capacity to absorb vast quantities of alcohol and still keep drinking.[23] When he sent Feng a bottle of brandy, Feng replied by sending him a bottle of water, a message that Wu failed to take in. An intense Chinese nationalist, Wu Peifu refused to enter the foreign concessions in China, a stance that was to cost him his life when he refused to go to the International Settlement or the French Concession in Shanghai for medical treatment.[23]

More typical was Marshal Zhang Zuolin, a "graduate of the University of the Green Forest" (i.e., a bandit), an illiterate who had a forceful, ambitious personality that allowed him to rise up from the leader of a bandit gang, be hired by the Japanese to attack the Russians during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–05 and become the warlord of Manchuria by 1916. He worked openly for the Japanese in ruling Manchuria. Zhang controlled only 3% of China's population but 90% of its heavy industry. The wealth of Manchuria, the support of the Japanese, and Zhang's hard-hitting, swift-moving cavalry made him the most powerful of the warlords.[22] His Japanese patrons insisted that he ensure a stable economic climate to facilitate Japanese investment, making him one of the few warlords who sought to pursue economic growth instead of just plundering.[23]

Zhang Zongchang, known as the "Dogmeat General" because of his love for the gambling game of that name, was described as having "the physique of an elephant, the brain of a pig and the temperament of a tiger". Writer Lin Yutang called Zhang "the most colorful, legendary, medieval, and unashamed ruler of modern China". Former Emperor Puyi remembered Zhang as "a universally detested monster" whose ugly, bloated face was "tinged with the livid hue induced by heavy opium smoking". A brutal man, Zhang was notorious for his hobby of smashing in the heads of prisoners with his sword, which he called "smashing melons". He loved to boast about the size of his penis, which became part of his legend. He was widely believed to be the most well endowed man in China, nicknamed "General Eighty-Six" as his penis when erect was said to measure up to a pile of 86 Mexican silver dollars (25.8 cm or 10.16 in). His harem consisted of Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Russian and two French women. He gave them numbers, as he could not remember their names, and then usually forgot the numbers.[23]

Other notable information on some of the above-mentioned major warlords:

- Zhang Zuolin, "Warlord of Manchuria", became Japan's ally against Russia during the Russo-Japanese War. He had also served as the military governor of Mukden since 1911.

- Feng Yuxiang was a soldier since childhood and like Wu, was a graduate of Paoting. He was baptized by a YMCA leader in 1913; he was known as the "Christian General" as he encouraged his troops to pursue Christianity. He seized Beijing in 1924 and demonstrated how easily a major Chinese city could be overthrown.[24]

The great ideological flexibility of warlords and politicians during this era can be well exemplified in the activities of Bai Lang, an important bandit leader. Even though he initially fought in support of the Qing dynasty with ultraconservative monarchists as well as warlords, Bai Lang later formed an alliance with republicans,[25] declared himself loyal to Sun Yat-sen and formed a "Citizen's Punitive Army" to rid China of all the warlords.[26]

Warlord armies

editGood iron does not make nails, good men do not make soldiers.

—Chinese proverb[27]

Many of the common soldiers in warlord armies were also bandits who took up service for a campaign and then reverted to banditry when the campaign was over. One politician remarked that when the warlords went to war with each other, the bandits become soldiers and when the war ended, the soldiers became bandits.[28] Warlord armies commonly raped or took many women into sexual slavery.[29] The system of looting was institutionalized, as many warlords lacked the money to pay their troops. Some took to kidnapping, and might send a hostage's severed fingers along with the ransom demand as a way of encouraging prompt payment.[26]

Besides bandits, the rank-and-file of the warlord armies tended to be village conscripts. They might take service in one army, get captured, then join the army of their captors before being captured yet again. Warlords usually incorporated their prisoners into their armies; at least 200,000 men who were serving in the army of Gen. Wu were prisoners he had incorporated into his own army.[citation needed] A survey of one warlord garrison in 1924 revealed that 90% of the soldiers were illiterate. In 1926 U.S. Army officer Joseph Stilwell inspected a warlord unit and observed that 20% were less than 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 m) tall, the average age was 14 and most walked barefoot. Stilwell wrote that this "scarecrow company" was worthless as a military unit. A British army visitor commented that, provided they had proper leadership, the men of northern China were "the finest Oriental raw material with a physique second to none, and an iron constitution". However, such units were the exception rather than the rule.[31]

Finances

editIn 1916 there were about a half-million soldiers in China. By 1922 the numbers had tripled, then tripled again by 1924; more than the warlords could support. For example, Marshal Zhang, the ruler of industrialized Manchuria, took in $23 million in tax revenues in 1925 while spending some $51 million. Warlords in other provinces were even more hard-pressed. One way of raising funds were taxes called lijin that were often confiscatory and inflicted much economic harm. For example, in Sichuan province there were 27 different taxes on salt, and one shipload of paper that was sent down the Yangtze River to Shanghai was taxed 11 different times by various warlords to the sum total of 160% of its value. One warlord imposed a tax of 100% on railroad freight, including food, even though there was a famine in his province. Taxes owed to the central government in Beijing on stamp and salt were usually taken by regional authorities. Despite all of the wealth of Manchuria and the support of the Japanese army, Marshal Zhang had to raise land taxes by 12% between 1922 and 1928 to pay for his wars.[32]

The warlords demanded loans from the banks. The other major revenue source besides taxes, loans and looting was the selling of opium, with the warlords selling the rights to grow and sell opium within their provinces to consortia of gangsters. Despite his ostensible anti-opium stance, Gen. Feng Yuxiang, "the Christian General", took in some $20 million per annum from opium sales. Inflation was another means of paying for their soldiers. Some warlords simply ran the money printing presses, and some resorted to duplicating machines to issue new Chinese dollars. The warlord who ruled Hunan province printed 22 million Chinese dollars on a silver reserve worth only one million Chinese dollars in the course of a single year, while Zhang in Shandong province printed 55 million Chinese dollars on a silver reserve of 1.5 million Chinese dollars during the same year. The illiterate Marshal Zhang Zuolin, who engaged in reckless printing of Chinese dollars, did not understand it was him who was causing the inflation in Manchuria, and his remedy was simply to summon the leading merchants of Mukden, accuse them of greed because they were always raising their prices, had five of them selected at random publicly shot and told the rest to behave better.[33]

Despite their constant need for money, the warlords lived in luxury. Marshal Zhang owned the world's biggest pearl, while Gen. Wu owned the world's biggest diamond. Marshal Zhang, the "Old Marshal", lived in a lavish palace in Mukden with his five wives, old Confucian texts and a cellar full of fine French wines, and needed 70 cooks in his kitchen to make enough food for him, his wives and his guests. Gen. Zhang, the "Dogmeat General", ate his meals off a 40-piece Belgian dinner service, and an American journalist described dinner with him: "He gave a dinner for me where sinful quantities of costly foods were served in a starving country. There was French champagne and sound brandy".[16]

Equipment

editThe warlords bought machine guns and artillery from abroad, but their uneducated and illiterate soldiers could not operate or service them. A British mercenary complained in 1923 that Wu Peifu had about 45 European artillery pieces that were inoperable because they had not been properly maintained.[34] At the Battle of Urga, the army of Gen. Xu Shuzheng, which had seized Outer Mongolia, was attacked by a Russian-Mongol army under the command of Gen. Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg. The Chinese might have stopped Ungern had they been capable of firing their machine guns properly, to adjust for the inevitable upward jerk caused by the firing; they did not, and this caused the bullets to overshoot their targets. The inability to use their machine guns properly proved costly: after taking Urga in February 1921, Ungern had his Cossacks and Mongol cavalry hunt down the remnants of Xu's troops as they attempted to flee south on the road back to China.[35] Chinese forces slaughtered most of a 350 strong White Russian forces in June 1921 under Colonel Kazagrandi in the Gobi desert, with only two batches of 42 men and 35 men surrendering separately as Chinese were wiping out White Russian remnants following the Soviet Red army defeat of Ungern Sternberg, and other Buryat and White Russian remnants of Ungern-Sternberg's army were massacred by Soviet Red Army and Mongol forces.[36]

During the crossing of the Russian-Chinese border in November 1922 and the disarmament, the Chinese authorities of Marshal Zhang Zuolin bought or received for free almost all the weapons of the Russian White Army, which left Vladivostok. In the border city of Kirin, the Chinese received a large number of the rifles, the machine guns, the cartridges and the grenades, the artillery pieces were sent immediately to the city of Changchun.[37]

When importing weapons became impractical, warlord armies either used locally-made copies of Western firearms (including ones in uncommon use such as the Franz Stock Pistol) or indigenous designs.[38][39]

Other forces

editBecause their soldiers were not able to use or take proper care of modern weapons, the warlords often hired foreign mercenaries, who were effective but always open to other offers. Russian émigrés who fled to China after the victory of the Bolsheviks were widely employed. One of the Russian mercenaries claimed that they went through Chinese troops like a knife through butter during one battle. The most highly paid of the Russian units was led by Gen. Konstantin Nechaev, who fought for Zhang Zongchang, the "Dogmeat General" who ruled Shandong province. Zhang Zongchang had Russian women as concubines.[40][41] Nechaev and his men were much feared. In 1926 they drove three armoured trains through the countryside, gunning down everyone they met and taking everything moveable. The rampage was stopped only when the peasants pulled up the train tracks, which led Nechaev to sack the nearest town.[42] Nechaev suffered a huge defeat at the hands of Chinese, when he and one armoured train under his command were trapped near Suichzhou in 1925. Their Chinese adversaries had pulled up the rail, and took this opportunity to massacre almost all Russian mercenaries on board the train. Nechaev managed to survive this incident, but lost a part of his leg during the bitter fighting.[43] In October 1926, Nechaev had 6 good armored trains, representing a significant military force.[44] In 1926 Chinese warlord Sun Chuanfang inflicted bloody death tolls upon the White Russian mercenaries under Nechaev's brigade in the 65th division serving Zhang Zongchang, reducing the Russian numbers from 3,000 to only a few hundred by 1927 and the remaining Russian survivors fought in armored trains.[45] During the Northern Expedition Chinese Nationalist forces captured an armoured train of Russian mercenaries serving Zhang Zongchang and brutalized the Russian prisoners by piercing their noses with rope and marching them in public through the streets in Shandong in 1928, described as "stout rope pierced through their noses".[46][47][48][49][50]

White Russian mercenaries defeated Muslim Uighurs in melee fighting when Uighurs tried to take Ürümqi on 21 February 1933 in the Battle of Ürümqi (1933).[51] Wu Aitchen mentioned that 600 Uyghurs were slaughtered in a battle by White Russian mercenaries in the service of the Xinjiang clique warlord Jin Shuren.[52][53] Jin Shuren would take Russian women as hostages to force their husbands to serve as his mercenaries.[54]

Hui Muslims fought brutal battles against White Russians and Soviet Red Army Russians at the Battle of Tutung and Battle of Dawan Cheng inflicting heavy losses on the Russian forces.[55]

Chinese forces killed many White Russian soldiers and Soviet soldiers in 1944–1946 when the White Russians of Ili and Soviet Red Army served in the Second East Turkestan Republic Ili national army during the Ili Rebellion.[56]

To defend themselves from the attacks of the warlord factions and armies, peasants organized themselves into militant secret societies and village associations which served as self-defense militias as well as vigilante groups. As the peasants usually had neither money for guns nor military training, these secret societies relied on martial arts, self-made weapons such as swords and spears, as well as the staunch belief in protective magic.[57][58] The latter was especially important, as the conviction of invulnerability was "a powerful weapon for bolstering the resolve of people who possessed few alternative resources with which to defend their meager holdings".[59] Magical rituals practiced by the peasants ranged from rather simple ones, such as swallowing charms,[60] to much more elaborate practices. For example, elements of the Red Spear Society performed secret ceremonies to confer invulnerability from bullets to channel the power of Qi and went into battle naked with supposedly bulletproof red clay smeared over their bodies.[26] The Mourning Clothes Society would perform three kowtows and weep loudly before each battle.[60] There were also all-female self-defense groups, such as the Iron Gate Society[26] or the Flower Basket Society.[60] The former would dress entirely in white (the color of death in China) and waved fans that they believed would deflect gunfire,[26] while the latter fought with a sword and a magical basket to catch their opponents' bullets.[60] Disappointed with the Republic of China and despairing due to the warlords deprivations, many peasant secret societies adopted millenarian beliefs,[59] and advocated the restoration of the monarchy, led by the old Ming dynasty. The past was widely romanticized, and many believed that a Ming emperor would bring a "reign of happiness and justice for all".[61][62]

Factions

editNorthern factions

editSouthern factions

edit- Kuomintang

- Chinese Communist Party

- Yunnan clique

- Guizhou warlords

- Old Guangxi clique

- New Guangxi clique

- Guangdong warlords

- Sichuan clique (Liu Wenhui until 1932 Liu Xiang post Two-Liu war)

- Hunan warlords

North

editThe death of Yuan Shikai split the Beiyang Army into two main factions. The Zhili and Fengtian clique were in alliance with one another, while the Anhui clique formed their own faction. International recognition was based on the presence in Beijing, and every Beiyang clique tried to assert their dominance over the capital to claim legitimacy.

Duan Qirui and Anhui dominance (1916–1920)

editWhile Li Yuanhong replaced Yuan Shikai as the President after his death, the political power was in the hands of Premier Duan Qirui. The government worked closely with the Zhili clique, led by Vice President Feng Guozhang, to maintain stability in the capital. Continuing military influence over the Beiyang government led to provinces around the country refusing to declare their allegiance. The debate between the President and the Premier on whether or not China should participate in the First World War was followed by political unrest in Beijing. Both Li and Duan asked Beiyang general Zhang Xun, stationed in Anhui, to militarily intervene in Beijing. As Zhang marched into Beijing on 1 July, he quickly dissolved the parliament and proclaimed a Manchu Restoration. The new government quickly fell to Duan after he returned to Beijing with reinforcements from Tianjin. As another government formed in Beijing, Duan's fundamental disagreements over national issues with the new President Feng Guozhang led to Duan's resignation in 1918. The Zhili clique forged an alliance with the Fengtian clique, led by Zhang Zuolin, and defeated Duan in the critical Zhili–Anhui War in July 1920.

Cao Kun and Zhili dominance (1920–1924)

editAfter the death of Feng Guozhang in 1919, the Zhili clique was led by Cao Kun. The alliance with the Fengtian was only one of convenience and war broke out in 1922 (the First Zhili–Fengtian War), with Zhili driving Fengtian forces back to Manchuria. Next, they wanted to bolster their legitimacy and reunify the country by returning Li Yuanhong to the presidency and restoring the National Assembly. They proposed that Xu Shichang and Sun Yat-sen resign their rival presidencies simultaneously in favour of Li. When Sun issued strict stipulations that the Zhili could not stomach, they caused the defection of KMT Gen. Chen Jiongming by recognizing him as governor of Guangdong. With Sun driven out of Guangzhou, the Zhili clique superficially restored the constitutional government that existed prior to Zhang Xun's coup. Cao bought the presidency in 1923 despite opposition by the KMT, Fengtian, Anhui remnants, some of his lieutenants and the public. In the autumn of 1924 the Zhili appeared to be on the verge of complete victory in the Second Zhili–Fengtian War until Feng Yuxiang betrayed the clique, seized Beijing and imprisoned Cao. Zhili forces were routed from the north but kept the center.

Duan Qirui return as chief executive (1924–1926)

editFeng Yuxiang's defection resulted in the defeat of Wu Peifu and the Zhili clique and forced them to withdraw to the south. The victorious Zhang Zuolin unpredictably named Duan Qirui as the new Chief Executive of the nation on 24 November 1924. Duan's new government was grudgingly accepted by the Zhili clique because, without an army of his own, Duan was now considered a neutral choice. In addition, instead of "President" Duan was now called the "Chief Executive", implying that the position was temporary and therefore politically weak. Duan called on Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang in the south to restart negotiations towards reunification. Sun demanded that the "unequal treaties" with foreign powers be repudiated and that a new national assembly be assembled. Bowing to public pressure, Duan promised a new national assembly in three months; however he could not unilaterally discard the "unequal treaties", since the foreign powers had made official recognition of Duan's regime contingent upon respecting these very treaties. Sun died on 12 March 1925 and the negotiations fell apart.

With his clique's military power in a shambles, Duan's government was hopelessly dependent on Feng Yuxiang and Zhang Zuolin. Knowing that those two did not get along, he secretly tried to play one side against the other. On 18 March 1926, a protest march was held against continued foreign infringement on Chinese sovereignty and a recent incident in Tianjin involving a Japanese warship. Duan dispatched military police to disperse the protesters, and in the resulting melee 47 protesters were killed and over 200 injured, including Li Dazhao, co-founder of the Communist Party. The event came to be known as the 18 March Massacre. The next month Feng Yuxiang again revolted, this time against the Fengtian clique, and deposed Duan, who was forced to flee to Zhang for protection. Zhang, tired of his double dealings, refused to restore him after re-capturing Beijing. Most of the Anhui clique had already sided with Zhang. Duan Qirui exiled himself to Tianjin and later moved to Shanghai where he died on 2 November 1936.

Zhang Zuolin and Fengtian (1924–1928)

editDuring the Second Zhili–Fengtian War, Feng Yuxiang changed his support from Zhili to Fengtian and forced the Beijing Coup which resulted in Cao Kun being imprisoned. Feng soon broke off from the Zhili clique again and formed Guominjun and allied himself with Duan Qirui. In 1926, Wu Peifu from the Zhili clique launched the Anti-Fengtian War. Zhang Zuolin took advantage of the situation, and entered Shanhai Pass from the Northeast and captured Beijing. The Fengtian clique remained in control of the capital until the Northern Expedition led by Chiang Kai-shek's National Revolutionary Army forced Zhang out of power in June 1928.

South

editThis section needs expansion with: More information regarding the 'Nanjing-Wuhan' split and the divisions inside the KMT. You can help by adding to it. (May 2020) |

The southern provinces of China were notably against the Beiyang government in the north, having resisted the restoration of monarchy by Yuan Shikai and the subsequent government in Peking after his death. Sun Yat-sen along with other southern leaders had formed a government in Guangzhou to resist the rule of the Beiyang warlords, and the Guangzhou government came to be known as part of the Constitutional Protection War.

Sun Yat-sen and "Constitutional protection" military junta in Guangzhou (1917–1922)

editIn September Sun was named generalissimo of the military government with the purpose of protecting the provisional constitution of 1912. The southern warlords assisted his regime solely to legitimize their fiefdoms and challenge Beijing. In a bid for international recognition, they also declared war against the Central Powers but failed to garner any recognition. In July 1918 southern militarists thought Sun was given too much power and forced him to join a governing committee. Continual interference forced Sun into self-imposed exile. While away, he recreated the Chinese Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang. With the help of KMT Gen. Chen Jiongming, committee members Gen. Cen Chunxuan, Adm. Lin Baoyi and Gen. Lu Rongting were expelled in the 1920 Guangdong–Guangxi War. In May 1921 Sun was elected "extraordinary president" by a rump parliament despite protests by Chen and Tang Shaoyi, who complained of its unconstitutionality. Tang left while Chen plotted with the Zhili clique to overthrow Sun in June 1922 in return for recognition of his governorship over Guangdong.

Reorganization of military junta in Guangzhou (1923–1925)

editAfter Chen was driven out of Guangzhou, Sun returned again to assume leadership in March 1923. The party was reorganized along Leninist democratic centralism, and the alliance with the Chinese Communist Party came to be known as First United Front. The Guangzhou government focused on training new officers through the newly created Whampoa Military Academy. In 1924, the Zhilii clique fell out of power, and Sun travelled to Beiping to negotiate terms of reunification with leaders from Guominjun, Fengtian and Anhui clique. He was unable to secure the terms as he died in March 1925 from illness. Power struggles within the KMT ensued after the death of Sun. The Yunnan–Guangxi War broke out as Tang Jiyao tried to claim party leadership. In the north, there were struggles led by Guominjun against Fengtian-Zhili alliance from November 1925 to April 1926. The defeat of Guominjun ended their reign in Beiping.

Nanjing-Wuhan Split (1927)

editIn April 1927, Commander-in-Chief of the NRA (National Revolutionary Army) Chiang Kai-Shek began a purge of leftists and communists in what is known as the Shanghai massacre. As a result of the massacre the Wuhan government chose to split from Chiang which resulted in him forming a new nationalist government in Nanjing.

Reunification

editChiang Kai-shek emerged as the protégé of Sun Yat-sen following the Zhongshan Warship Incident. In the summer of 1926, Chiang and the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) began the Northern Expedition with the hopes to reunify China. Wu Peifu and Sun Chuanfang of the Zhili clique were subsequently defeated in central and eastern China. In response to the situation, the Guominjun and Yan Xishan of Shanxi formed an alliance with Chiang to attack the Fengtian clique together. In 1927, Chiang initiated a violent purge of Communists in the Kuomintang, which marked the end of the First United Front.

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA) formed by the KMT swept through southern and central China until it was checked in Shandong, where confrontations with the Japanese garrison escalated into armed conflict. The conflicts were collectively known as the Jinan incident of 1928.

Although Chiang had consolidated the power of the KMT in Nanking, it was still necessary to capture Beiping (Beijing) to claim the legitimacy needed for international recognition. Yan Xishan moved in and captured Beiping on behalf of his new allegiance after the death of Zhang Zuolin in 1928. His successor, Zhang Xueliang, accepted the authority of the KMT leadership, and the Northern Expedition officially concluded.

The politics of the Nanjing Decade of Kuomintang leadership over China were deeply shaped by the compromises with warlords that had allowed the victory of the Northern expedition. Most provincial leaders were military commanders who joined the party only during the expedition itself, when the warlords and their administrators were absorbed wholesale by Chiang. Although dictatorial, Chiang did not have absolute power as party rivals and local warlords posed a constant challenge.[63]

Despite the reunification, there were still ongoing conflicts across the country. Remaining regional warlords across China chose to cooperate with the Nationalist government, but disagreements with the Nationalist government and regional warlords soon broke out into the Central Plains War in 1930. Northwest China erupted into a series of wars in Xinjiang from 1931 to 1937. Following the Xi'an Incident in 1936, efforts began to shift toward preparation of war against the Japanese Empire.

The warlords continued posing problems for the National Government up until the communist victory in 1949, when many turned on the KMT and defected to the CCP, such as Yunnanese warlord Lu Han, whose troops had earlier been responsible for receiving the surrender of the Japanese in Hanoi and had engaged in widespread looting.[64]

Although Chiang was generally not considered personally corrupt, his power was dependent on balancing between the various warlords. Although he understood and expressed hatred at the fact that KMT corruption was driving the public to the communists, he continued dealing with warlords, tolerating incompetence and corruption while undermining subordinates who became too strong so as to preserve unity. After the Japanese surrender, warlords turned against the KMT.[65]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ McCord 1993, pp. 245–250.

- ^ McCord 1993, p. 288.

- ^ Jordan, Donald A. (1976). The Northern Expedition: China's National Revolution of 1926–1928. University of Hawaiʻi Press. pp. 4–6, 32–39. ISBN 9780824880866.

- ^ Waldron, Arthur (1991). "The Warlord: Twentieth-century Chinese Understandings of Violence, Militarism, and Imperialism". American Historical Review. 96 (4): 1085–1086. JSTOR 2164996.

- ^ Henry McAleavy, "China Under The Warlords, Part I". History Today (April 1962) 12#4 pp. 227–233; and "Part II" (May 1962), 12#5 pp 303–311.

- ^ Maochun Yu (2002), "The Taiping Rebellion: A Military Assessment of Revolution and Counterrevolution", in David A. Graff & Robin Higham (eds.), A Military History of China 149

- ^ Kwang-ching Liu; Richard J. Smith (1980). "The Military Challenge: The North-west and the Coast". In John King Fairbank; Kwang-Ching Liu; Denis Crispin Twitchett (eds.). Late Ch'ing, 1800–1911. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 11, Part 2 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- ^ McCord, Edward A. (1993). The Power of the Gun: The Emergence of Modern Chinese Warlordism. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 29, 39, 44.

- ^ John King Fairbank; Kwang-Ching Liu; Denis Crispin Twitchett, eds. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800–1911. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 11, Part 2 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 540–542, 545. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- ^ John King Fairbank; Kwang-Ching Liu; Denis Crispin Twitchett, eds. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800–1911. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 11, Part 2 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- ^ Patrick Fuliang Shan, Yuan Shikai: A Reappraisal (University of British Columbia Press, 2018, ISBN 978-0-7748-3778-1)

- ^ Fairbank, John; Reischauer, Edwin; Craig, Albert (1978). East Asia: Tradition and Transformation. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 754. ISBN 978-0-395-25812-5.

- ^ Fairbank, John; Reischauer, Edwin; Craig, Albert (1978). East Asia: Tradition and Transformation. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 758. ISBN 978-0-395-25812-5.

- ^ Roberts, J. A. G. (1989). "Warlordism in China". Review of African Political Economy. 45/46 (45/46): 26–33. doi:10.1080/03056248908703823. JSTOR 4006008.

- ^ Pye, Lucian W. (1971). Warlord politics: conflict and coalition in the modernization of Republican China. Praeger. p. 168. ISBN 9780275281809.

- ^ a b Fenby (2004), p. 104.

- ^ Fenby (2004), p. 107.

- ^ Fenby (2004), pp. 107–108.

- ^ "Chinese Civil War Russian Armored Trains - Paris Tour Guide". Retrieved 23 May 2024.[better source needed]

- ^ Fenby (2004), p. 112.

- ^ Laikwan, Pang (2024). One and All: The Logic of Chinese Sovereignty. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503638815.

- ^ a b Fenby (2004), p. 103.

- ^ a b c d Fenby (2004), p. 102.

- ^ Fairbank, John; Reischauer, Edwin; Craig, Albert (1978). East Asia: Tradition and Transformation. Boston: Hougton Mifflin Company. pp. 761–762. ISBN 978-0-395-25812-5.

- ^ Billingsley (1988), pp. 56, 57, 59.

- ^ a b c d e Fenby (2004), pp. 105–106.

- ^ Lary (1985), p. 83.

- ^ Fenby (2004), pp. 104–106, 110–111.

- ^ Fenby (2004), p. 106.

- ^ Jowett (2014), pp. 87, 88.

- ^ Fenby (2004), pp. 110–111.

- ^ Fenby (2004), p. 108.

- ^ Fenby (2004), pp. 109–110.

- ^ Fenby (2004), p. 110.

- ^ Palmer, James The Bloody White Baron The Extraordinary Story of the Russian Nobleman Who Become the Last Khan of Mongolia, New York: Basic Books, 2009 pages 149, 158.

- ^ Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian (illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 339. ISBN 1135765960.

- ^ M.Blinov. "Chinese Civil War Armies". Paris Guide – France in the old photos: famous sights, museums and WW1 – WW2 battlefields. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ McCollum, Ian (2021). Pistols of the Warlords: Chinese Domestic Handguns, 1911 – 1949. Headstamp Publishing. pp. 28–515. ISBN 9781733424639.

- ^ Duan, Lei (August 2017). The Prism of Violence: Private Gun Ownership in Modern China, 1860-1949 (PhD thesis). Syracuse University. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022.

- ^ Weirather, Larry (2015). Fred Barton and the Warlords' Horses of China: How an American Cowboy Brought the Old West to the Far East. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 42. ISBN 978-0786499137.

- ^ "CHINA: Potent Hero". TIME. 24 September 1928. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Fenby (2004), p. 111.

- ^ Bisher, Jamie (2005). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 297. ISBN 0714656909.

- ^ "Chinese Civil War Russian Armored Trains - Paris Tour Guide". Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Kwong, Chi Man (2017). War and Geopolitics in Interwar Manchuria: Zhang Zuolin and the Fengtian Clique during the Northern Expedition. Vol. 1 of Studies on Modern East Asian History (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 155. ISBN 978-9004340848.

- ^ Fenby, Jonathan (2003). Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the China He Lost (illustrated ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 176. ISBN 0743231449.

- ^ Fenby, Jonathan (2009). Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the China He Lost (reprint ed.). Hachette Books. p. 176. ISBN 978-0786739844.

- ^ Fenby, Jonathan (2010). The General: Charles De Gaulle and the France He Saved. Simon and Schuster. p. 176. ISBN 978-0857200679.

- ^ Fenby, Jonathan (2008). Generalissimo: Modern China: The Fall and Rise of a Great Power, 1850 to the Present. HarperCollins. p. 194. ISBN 978-0061661167.

- ^ Fenby, Jonathan (2013). The Penguin History of Modern China: The Fall and Rise of a Great Power, 1850 to the Present (2, illustrated ed.). Penguin Books. p. 194. ISBN 978-0141975153.

- ^ Forbes, Andrew D. W. (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949 (illustrated ed.). CUP Archive. pp. 101–103. ISBN 0521255147.

- ^ Forbes, Andrew D. W. (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949 (illustrated ed.). CUP Archive. p. 294. ISBN 0521255147.

- ^ Wu, Aichen (1984). Turkistan Tumult. Oxford in Asia paperbacks (illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 0195838394.

- ^ Forbes, Andrew D. W. (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949 (illustrated ed.). CUP Archive. p. 100. ISBN 0521255147.

- ^ Forbes, Andrew D. W. (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949 (illustrated ed.). CUP Archive. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0521255147.

- ^ Forbes, Andrew D. W. (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949 (illustrated ed.). CUP Archive. p. 178. ISBN 0521255147.

- ^ Chesneaux (1972), pp. 5, 6.

- ^ Perry (1980), pp. 203, 204.

- ^ a b Perry (1980), p. 195.

- ^ a b c d Perry (1980), p. 204.

- ^ Novikov (1972), pp. 61–63.

- ^ Perry (1980), p. 232.

- ^ Zarrow, Peter (2006). China in War and Revolution, 1895–1949. Routledge. pp. 248–249. ISBN 1134219768.

- ^ Gibson, Richard Michael (2011). "1". The Secret Army: Chiang Kai-shek and the Drug Warlords of the Golden Triangle. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470830215.

- ^ Kurtz-Phelan, Daniel (2019). "3, 5". The China Mission: George Marshall's Unfinished War, 1945–1947. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393243086.

Works cited

edit- Billingsley, Phil (1988). Bandits in Republican China. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- Chan, Anthony B. (1 October 2010). Arming the Chinese: The Western Armaments Trade in Warlord China, 1920–28, Second Edition. UBC Press. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-0-7748-1992-3.

- Chesneaux, Jean (1972). "Secret Societies in China's Historical Evolution". In Jean Chesneaux (ed.). Popular Movements and Secret Societies in China 1840-1950. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 1–21.

- McCord, Edward A. (1993), The Power of the Gun: The Emergence of Modern Chinese Warlordism, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

- Fenby, Jonathan (2004). Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the China He Lost. London. ISBN 9780743231442.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jowett, Philip. Chinese Warlord Armies 1911–30 (Men-at-Arms Series 2010)

- Lary, Diana. “Warlord Studies.” Modern China 6#4 (1980), pp. 439–470. online

- Lary, Diana (1985). Warlord Soldiers: Chinese Common Soldiers 1911–1937. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-13629-7.

- McAleavy, Henry. "China Under The Warlords, Part I." History Today (Apr 1962) 12#4 pp 227–233; and "Part II" (May 1962), 12#5 pp 303–311.

- Michael, Franz H. “Military Organization and Power Structure of China during the Taiping Rebellion.” Pacific Historical Review 18#4 (1949), pp. 469–483. online

- Novikov, Boris (1972). "The Anti-Manchu Propaganda of the Triads, ca. 1800–1860". In Jean Chesneaux (ed.). Popular Movements and Secret Societies in China 1840–1950. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 49–63.

- Sheridan, James E. (1975). China in Disintegration: The Republican Era in Chinese History, 1912–1949. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0029286104.

- Waldron, Arthur (1991). "The Warlord: Twentieth Chinese Understandings of Violence, Militarism, and Imperialism". American Historical Review. 96 (4): 1073–1100. doi:10.2307/2164996. JSTOR 2164996.

- —— (1995). From War to Nationalism: China's Turning Point, 1924–1925. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52332-5.

- Jowett, Philip S. (1997). Chinese Civil War Armies 1911–49. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-665-1.[permanent dead link]

- Jowett, Philip S. (2014). The Armies of Warlord China 1911–1928. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0764343452.

- Jowett, Philip S. (2017). The Bitter Peace. Conflict in China 1928–37. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445651927.

- Perry, Elizabeth J. (1980). Rebels and Revolutionaries in North China, 1845-1945. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.