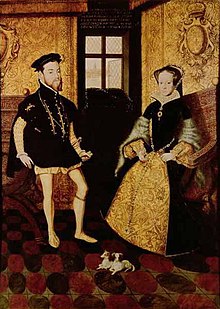

Wedding of Mary I of England and Philip of Spain

Mary I of England (1516–1558) and Philip of Spain (later Philip II; 1527–1598) married at Winchester Cathedral on Wednesday 25 July 1554.[2]

Making a marriage

editThere was some opposition in England to the new Queen marrying a foreign prince. A Spanish chronicle refers to the xenophobic beliefs of the English people, and Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, Bishop of Arras (who had obtained the oil used to anoint Mary at her coronation) wrote that the English would only accept the marriage with the greatest difficulty. Attitudes however were much more nuanced, especially in London and other centres of international trade hosting immigrant communities.[3] Opponents of the marriage plan among the privy counsellors and royal household included Robert Rochester, Francis Englefield, and Edward Waldegrave.[4]

In November, Mary of Hungary, Governor of the Netherlands, agreed to send a portrait by Titian of Philip dressed in wolfskin to Mary. She had not yet seen her intended husband. The picture was possibly brought to England a few months later, in March 1554, by Juan Hurtado de Mendoza.[5]

In December 1553, the Privy Council of England discussed a draft of articles for the marriage. Philip would share in Mary's titles and aid her administration. Mary, if Philip died before her, would enjoy a dowry or jointure income from Spanish lands and territories including Brabant, Flanders, Hainault and Holland. Margaret of York had the same jointure in 1468. Possibly, the final articles would include a contract preventing Philip appointing foreigners to English offices. He would accept a number of English courtiers in his household. He would not be allowed to take Mary or their children abroad, or send English treasure, ships, or military equipment abroad.[6] During their marriage, Philip had a council in England, and intervened in diplomacy with Scotland and other matters.[7]

Opposition to the wedding found leaders in Thomas Wyatt the Younger and his companions who organised a rebellion against Mary. Wyatt brought an armed force to London in February 1554. Mary made a speech in London's Guildhall, showing that by her coronation ring she was "wedded to the realm and law".[8] Wyatt surrendered at Ludgate. Lady Jane Grey, a Protestant figurehead, was executed on 12 February and Wyatt on 11 April.[9] Elizabeth was sent to the Tower of London on 18 March,[10] and according to John Foxe, made her famous speech at Traitors' Gate.[11]

An English household for Philip

editA commission in England organised an English household for Philip. 350 servants and courtiers were nominated. The Earl of Arundel would be its head, and he would Lord Steward of both households. John Williams was to be his Chamberlain, and John Huddlestone, his Vice-Chamberlain. The gentlemen of the Privy Chamber would be sons of peers of England, including Thomas Radclyffe, Baron FitzWalter. Philip would organise his own chapel.[12] According to the marriage contract, pensions and rewards for a "convenient number" of his English servants would come from Spanish revenues.[13]

Parliament and the marriage contract

editThe English Parliament made provision for the marriage by the Act for the Marriage of Queen Mary to Philip of Spain passed in April 1554.[14] Mary's dowry was appointed to be "in the like manner" as Margaret of York who married Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy in 1468. The marriage contract acknowledged Anglo-Imperial treaties of 1542 and 1546, which facilitated trade in the North Sea to Flanders and other markets. The contract instructed Philip not to innovate or reform the old established law and customs of England and its realms. If there were no children, and Mary died, Philip had no particular rights in the succession.[15] Philip was not completely happy with these details and delayed his departure, and Mary did not wish to marry in Lent.[16]

According to a French report, Mary began a partial reconciliation with Elizabeth, calling her "sister" and restoring her portrait to a gallery in the palace placed next to hers. Elizabeth was taken to Woodstock Palace.[17]

Surrey and Hampshire

editThe Spanish courtier Pedro Dávila y Zúñiga, Marques de las Navas (1498–1567) arrived in England at Plymouth in June and was met by the Earl of Pembroke. Edward Sutton, 4th Baron Dudley, wrote to the royal council in London from Basing describing the reception of the Marquess de las Navas, who had travelled to Shaftesbury and to Wilton House, where he enjoyed hare coursing and planned to meet Mary at Guildford Castle.[18] He brought a gift of a diamond jewel from Philip.[19][20][21] A courtier, Juan de Varaona, recorded that Mary wore the diamond and ruby presented by de las Navas on the wedding day.[22] Mary wrote to the Mayor of Exeter from Guildford on 22 June, thanking him for looking after the Marquess.[23] The Marquess would act as Mary's interpreter for her Spanish guests.[24]

Philip left La Coruña on 12 July 1554. He sailed in the Espíritu Santo commanded by Martín Jimenez de Bertendona.[25] His fleet was escorted by 31 English ships, including the Mary Willoughby and the Salamander.[26]

Mary went to Farnham Castle,[27] then stayed a night at John Norton's house at Tisted (Norton was a steward of the Bishop of Winchester), and then to the Palace at Bishop's Waltham.[28] She heard news of Philip's embarkation by 17 July and wrote to Lord Clinton to approach her court and await the king at Guildford, Farnham, or Alton.[29]

Arriving at Southampton on 20 July,[30] Philip went first to the Holyrood Church to give thanks for his safe voyage.[31] Philip was greeted by Anthony Browne, who told him that Mary had appointed him his master of his horse.[32] Mary and her council had made plans for the wedding and Philip's arrival, and he was perhaps not fully informed. He sent the diplomat Simon Renard to find out more details. His entourage found that Philip was accorded second place to Mary, and this reflection seems to colour their accounts of the festivities.[33]

The arrival of Philip at Southampton was proclaimed in London on Saturday 21 July. The Mayor of London ordered celebratory bonfires. Aristocrats were summoned to Winchester.[34]

Mary went to Winchester, where the Mayoress Helen Lawrence (wife of William Lawrence) and her sisters, who were standing in line on a carpet, presented her with a gold cup. After attending a service in the cathedral she went to her lodging at Wolvesey Castle, "with a right goodly company of noblewomen and ladies".[35] On 22 July, Philip's favourites Ruy Gómez de Silva and Juan Rodriguez de Figueroa came to Winchester bringing Mary another jewel.[36]

Preparations at Winchester

editThe surveyor of royal works, Laurence Bradshawe was ordered to make some modifications at the Bishop's Palace in Winchester, Wolvesey Castle, making a new door from the hall to an audience chamber for the queen.[37]

Mary's usher, John Norris, was asked to build the dais and stages and decorate the cathedral with hangings and tapestry.[38] He later wrote a treatise describing the usher's duties,[39] and included a sketch of the stage at Winchester.[40]

Wedding at Winchester

editAn account of the wedding was written by a Scottish observer, John Elder, as a letter to Robert Stewart, Bishop of Caithness.[41] Elder is best known as a tutor of Lord Darnley.[42] Elder's letter shares some material with an account of the wedding included in editions of Robert Fabyan's New Chronicle.[43] There were several narratives of the marriage, published in English, Spanish, Italian, German and Dutch. The publications were intended to celebrate to glory of the Habsburgs and the benefits of the marriage to England and Catholic Europe. Subsequent chronicles seem to follow the narratives closely, though English versions are less enthusiastic about the match.[44]

Philip arrived in Winchester on 23 July riding through the rain on a white horse. He changed horses at the Hospital of St Cross.[45] He went to the cathedral and then to his lodgings in the Dean's House, adjacent to Wolvesey Castle. They met for half-an-hour. Juan de Barahona, Philp's steward, wrote that Philip reached Mary by a spiral stair from the castle garden.[46] Both Elder and Muñoz relate that Mary taught Philip how to say "Goodnight" to the English lords.[47] Although Mary's mother was Spanish, it is not known for sure how well she spoke the language. A Venetian diplomat Giovanni Michieli, later mentioned that she understood Spanish but did not speak it.[48]

Andrés Muñoz, a servant in the Spanish entourage,[49] wrote that the couple walked in the water meadows by the River Itchen. The Spanish courtiers identified their experience of England with the locations of romance stories in books of chivalry.[50] Juan de Barahona noted the Isle of Wight as the "Insula Firme" in the Castilian romance Amadís de Gaula.[51]

On Tuesday, Mary sent her tailor Richard Tisdale to Philip with a choice of cloaks to wear for the wedding.[52] They met again in the great hall of Wolvesey Castle.[53] The room was called "Poncia", according to Muñoz. The name may derive from John of Pontoise, a Bishop of Winchester.[54] Mary's gentlewomen wore purple velvet.[55] On this occasion Philip wore a black coat embroidered with silver, and white hose on his legs.[56]

Winchester Cathedral

editThey were married on Wednesday 25 July, the Feast of Saint James, patron saint of Spain. Philip entered the church at 11 o'clock, Mary came half an hour after. According to Jean de Vandenesse, both were dressed in rich cloth of gold (drap d'or frizé bien riche), and Mary wore many valuable jewels on her head and body.[57]

The Earl of Derby carried a sword of state. Don Juan de Figueroa, Regent of Naples, gave Bishop Gardiner a document from Charles V declaring that Philip was the sovereign of Naples, and Duke of Milan, and had the status of a monarch.[58] Mary seems to have made the decision for this public announcement to be part of the ceremony.[59]

Mary had chosen a plain gold ring with no stone, saying that had been the custom with maidens of old.[60] Edward Stanley, 3rd Earl of Derby gave the bride away. After the marriage with the ring, Philip and Mary processed to the high altar in the quire of the cathedral.[61]

At the conclusion of the service, Philip and Mary were proclaimed joint rulers.[62] The herald, Garter King of Arms, Gilbert Dethick, proclaimed their titles in Latin, French, and English, as "King and Queen of England, France, Naples, Jerusalem, and Ireland. Defenders of the Faith, Princes of Spain and Sicily, Archdukes of Austria, Dukes of Milan, Burgaundy, and Brabant, Counts of Habsbury, Flanders and Tyrol".[63]

A story about Mary's death and Nicholas Throckmorton mentions a gold ring decorated with black enamel, described (in verse) as Mary's espousal ring, a gift from Philip. It is not clear if this was the ring used in the ceremony or a betrothal gift.[64][65]

Costume for a co-monarchy

editDescriptions of the costumes in the narrative accounts seem to vary in detail, evoking primarily the cost and luxury of fabrics and embroidery. A gown of Mary's described in a later royal inventory may have been the one worn on her wedding day; a French gown of rich gold tissue, with a border of purple satin, all over embroidered with purls of damask gold and pearls, lined with purple taffeta. The embroiderer was called Guilliam Brallot. Elizabeth I's tailors unpicked the small pearls from this garment for re-use.[66] The pearls from the gown seem to have been appraised for sale in October 1600, including 250 oriental pearls worth £206 and "meaner" sized pearls worth £40.[67]

The French diplomat Antoine de Noailles wrote of Mary's costume at Winchester embroidered with "infinite jewels", elle a prins bonne part sa coustume suivant ses habits et personne couverts de pierreries infinies.[68] Noailles had previously noted that the ladies of Mary's court had discarded the sombre garments worn at the court of Edward VI and were dressed in gowns of rich cloth and colour in French fashions (apparently a comment on Protestant tastes in dress).[69] The Venetian ambassador Giacomo Soranzo wrote that on state occasions Mary wore wide sleeves in the French fashion.[70] The costume of Englishwomen in general, he thought, was French in character.[71] One of the Spanish accounts mentions that women in London wore masks or veils when walking outside, and black stockings.[72]

An Italian account of the wedding, published by Guido Raviglio Rosso in 1558, described her costume as French in style, with gown and robe of piled velvet brocade (black velvet according to Andrés Muňoz), with a long train, and embellished with very large pearls and diamonds of great size. Her turned-back lined sleeves were dressed with gold, enriched with pearls and with diamonds; her veil with two diamond-set borders. On her breast she wore the costly diamond sent to her by Philip from Spain. Her skirts were of white satin, embroidered with silver, the stockings scarlet, she wore black velvet shoes.[73]

Raviglio Rosso's description is related to other similarly worded Italian accounts of Mary's costume printed as festival books, Il trionfo delle superbe nozze fatte nel sposalitio del principe di il Spagna [et] la regina d'Inghilterra, and the Narratione assai piu particolare. The Narratione says Mary's hair was dressed and ornamented in French or Flemish style.[74] The spelling differs slightly, and the version printed as Il trionfo delle superbe nozze does not mention shoes or stockings.[75] These texts describe the brocade of Mary's gown as "riccio sopra riccio".[76]

The jewel sent by Philip was a "diamond mounted on a setting in the form of a rose, with a huge pearl hanging down onto the chest".[77] This jewel, including a square "table diamond" and a pendant pearl may be represented in her portraits by Hans Eworth and Anthonis Mor.[78] A large pearl with a complex history known as "La Peregrina", once owned by Elizabeth Taylor, was thought to have been Mary's.[79] Estimates of the values of the diamond, at 60,000 scudi, and the pendant pearl, at 5,000 scudi, were given in the Italian Narratione.[80]

Juan de Varaona said she wore the jewel brought by the Marquess de las Navas between her breasts, including a ruby and a diamond, "en medios de los pechos el diamente y rubí que le invió el Rey con el Marques de las Navas". Mary included the table diamond in her will.[81] Varaona also states that their cloaks were in the French style, while Mary's hair and hat or headdress of black velvet embroidered with pearls was in the English fashion.[82]

Their matching brocade clothes were white cloth of gold, or made of white brocade with matching cloaks or mantles of cloth of gold trimmed with velvet.[83] Some part of Philip's outfit had been selected by Mary, as gifts of English-style dress which may have helped to define him as Mary's husband.[84] She had sent him alternative cloaks or robes, a French despatch mentions tissue of cloth of gold and of silver,[85] and he had chosen one that was less ostentatious. Philip later recorded these garments in an inventory of precious goods remaining at Whitehall Palace;

A French robe of cloth of gold adorned with crimson velvet and thistles of curled gold, lined in crimson satin, with twelve buttons made of four pearls each on each sleeve, making twenty-four in all. I wore this at my wedding, and the Queen sent it to me for that purpose.

Another French robe of cloth of gold, with the roses of England and pomegranates [an embem of Catherine of Aragon] embroidered on it, adorned with drawn gold beads and seed pearls. The sleeves carry eighteen buttons, nine on each, made of table diamonds. The lining is of purple satin. This was given to me by the Queen for me to wear on our wedding day in the afternoon, but I do not think I wore it because it seemed to me ornate.[86]

Philip wore a jewelled collar of the Order of the Garter which she had commissioned for 7 or 8,000 crowns. The clothes emphasised their co-monarchy and political union.[87] The French fashion was not particularly to the taste of Spanish observers, being the costume of their political rivals in Europe.[88]

Dancing at Wolvesey Castle

editAfter the wedding, the royal couple dined in the Bishop's Palace, Wolvesey Castle.[89] There was a tall buffet or cupboard displaying 120 pieces of gold and silver plate. The buffet had six shelves or degrees, a mark of high honour.[90]

Mary and Philip sat on a raised dais under a canopy. On the right side of the hall there was a table for lords and gentlemen, ladies and gentlewomen sat on the left side.[91] Muñoz says the diners were Spanish, English, German, Hungarian, Bohemian, Polish, Flemish, Italian and Irish, and there was an Indian, hasta un seňor indiano, porque hubiese indio.[92] After the meal the Spanish guests chatted with the ladies in such Latin as they could muster. They had brought perfumed gloves as gifts but the language barrier hindered the customary formalities of gift giving.[93]

Edward Underhill wrote about his experience as a server at the meal. His presence at Winchester was questioned by the usher John Norris. One of Mary's valets, John Calverley (a brother of Underhill's fellow veteran Sir Hugh Calverley of Cheshire, whose ancestor was reputed to have married an Aragonese princess),[94] and Humphrey Radcliffe spoke in his favour.[95] Underhill managed to secure a whole venison pie for himself.[96] He wrote that the Spanish lords were jealous of the dance moves of Lord Braye and Master Carew.[97][98] John Elder described the Spanish nobles dancing with "the faire ladyes and the moste beutifull nimphes of England" as a sight from "an other worlde".[99]

A Spanish account says that Philip ordered two diplomats, Pedro Lasso de Castilla and Hernando de Gamboa, to dance a Spanish Alemana, and then Mary and Philip followed. After this there were other dances, following by supper.[100] Munoz thought the English gentlewomen's Spanish-style dancing was not quite as splendid as their English dance.[101] The Alemana was a popular dance at the Spanish court. Twelve male masquers dressed as gods and nymphs had danced an Alemana before Philip at Brussels at Mardi Gras in February 1550, including his favourite Ruy Gómez de Silva who was present at Winchester.[102] There was another ball on Sunday evening, and on subsequent days, the ladies of the court who were not attending in the queen's chamber were in the hall or antechamber of Wolvesey Castle dancing or conversing with guests.[103]

Festival decoration: a marriage of sable and silver

editA 16th-century chair in Winchester Cathedral covered with velvet (velvet not original) is thought to have been used at the wedding.[104] A fragment of painted decoration on timber boards painted in white and black, now displayed in the Westgate Museum, with portrait medallions and the motto 'Vive le Roi' and the initials of John White, warden of Winchester College, is probably connected with the wedding festivities.[105] The design was recreated at Stirling castle in 2010.[106]

John Elder mentions other painted inscriptions in black and white, and he equates these colours with sable and silver in heraldry, an association which likely held with the use of black and white in the wedding costume.[107] Andrés Muňoz developed a theme of gold and white or silver in his account. Philip was silver in deference to Mary's gold. During the service in the cathedral, Mary was always placed to the right, and Philip to the left, considered the secondary position.[108] at dinner, Philip was served with silver plates, while Mary's were gold.[109]

Progress to London and the Royal Entry

editThe Spanish party went to Winchester Castle to see King Arthur's Round Table displayed in the Great Hall, where it remains.[110] On 28 July, the ambassador of Charles V, Pedro Lasso de Castilla gave Mary a diamond jewel and a large pearl. This pearl was perhaps worn as a pendant with the other jewels and depicted in Mary's portraits.[111] One of the Italian accounts, the Narratione assai piu particolare, says that Mary wore a pendant pearl on her wedding day.[112]

After continuing the festivities at Winchester with masques and sports, Mary and Philip went to Basing House, and in August progressed to Reading, and Windsor Castle.[113] Philip was installed as a member of the Order of the Garter.[114] On Tuesday 7 August there was hunting in Windsor forest over a four or five mile long course or "toyle", probably in the Little Park where deer were killed with crossbows.[115] From Richmond Palace they went by boat to Suffolk Place in Southwark. On 19 August, they made their Royal Entry to London.[116] Some details of these days are known from a journal written by Jean de Vandenesse.[117] Noailles was invited to Southwark at short notice and made his excuses.[118]

The ceremonial route and shows in the city were similar to previous royal entries, including Mary's entry before her coronation in September 1553, but celebrated both Philip and Mary and an international outlook.[119] The first pageant in Gracechurch Street included the Nine Worthies and an image of Henry VIII with a book and the caption verbum dei, the word of God. Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, objected to this image as it appeared to be Protestant in character, and the painter was asked to make changes.[120] One of the organisers, John Sturgeon, was a haberdasher and Protestant, a friend of Hugh Latimer, who had contributed to Philip's entry to Antwerp in 1549. Other imagery presented included Gogmagog and Corineus Britannus, a legendary archer who had fought with the Trojan leader Brutus to defeat the primitive giants of Albion.[121] Pageants in the leather tanner's street and Cornhill represented other famous Philips, from the Apostle to the husband of Joanna of Castile.[122]

Mary and Philip ended their ceremonial route at St Paul's Cathedral and retired to Westminster Palace. On Tuesday 21 August they rode to Westminster Abbey. As Mary entered the church her train was carried by Elizabeth, Marchioness of Winchester and (according to a manuscript held by the Ashmolean Museum) Anne of Cleves.[123] Anne of Cleves had written to Mary from Hever on 4 August asking to attend the King and Queen in London.[124] Anne of Cleves had attended Mary's coronation in the Abbey on 1 October 1553. After the service in the Abbey was sung by the Spanish men of the chapel, Philip visited the tomb of Henry VII.[125]

Another pageant represented Mary and Philip's common descent from Edward III of England, as a literal family tree.[126] Andrés Muñoz did not describe the Royal Entry, but he concluded his account with remarks on the history of Britain, mentioning King Arthur's round table, Brutus, and the giants.[127]

A masque at court in October involved courtiers dressed as mariners.[128] Preparations were made for a Spanish-style bullfight at Smithfield in October, on St Luke's Day, but this entertainment was postponed.[129] A huge quantity of Spanish silver was coined in the Tower of London in October, Philip's commitment of treasure to the English money supply and the financing of his English household.[130] On 25 November, near St Pauls or at the court gate of Westminster Palace, Philip took part in the traditional Spanish pastime of juegó de cañas, an equestrian team sport possibly of Arabic origin.[131]

References

edit- ^ Martin Biddle, Beatrice Clayre, Michael Morris, 'The Setting of the Round Table', Martin Biddle, King Arthur's Round Table: An Archaeological Investigation (Boydell, 2000), p. 69.

- ^ Mitchell Gould, 'Philip II of Spain: King, Consort, Son', Aidan Norrie, Carolyn Harris, J. L. Laynesmith, Danna R. Messer, Elena Woodacre, Tudor and Stuart Consorts: Power, Influence, and Dynasty (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), p. 167.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), pp. 57, 140–146.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), p. 59.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), p. 106.

- ^ C. S. Knighton, Calendar State Papers Domestic, Mary (London: HMSO, 1998), pp. 13–15 no. 24.

- ^ Gonzalo Velasco Berenguer, 'The Select Council of Philip I: A Spanish Institution in Tudor England, 1555–1558', The English Historical Review, 139:597 (April 2024), pp. 326–359. doi:10.1093/ehr/cead216

- ^ Alice Hunt, The Drama of Coronation: Medieval Ceremony in Early Modern England (Cambridge, 2008), p. 133: Sarah Duncan, Mary I: Gender, Power, and Ceremony in the Reign of England's First Queen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 36: Richard Grafton, Chronicle at Large, vol. 2 (London, 1809), p. 539: David Loades, Mary Tudor (Basil Blackwell, 1989), p. 214.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), pp. 86, 90.

- ^ John Gough Nichols, Chronicle of the Grey Friars of London (London: Camden Society, 1852), p. 88.

- ^ The Acts and Monuments of John Foxe, 8 (London, 1839), p. 609

- ^ David Loades, Mary Tudor: A Life (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989), p. 204.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), pp. 68, 70–71.

- ^ Robert Tittler & Judith Richards, The Reign of Mary I (Routledge, 1983), p. 24: Judith M. Richards, 'Mary Tudor as Sole Quene?: Gendering Tudor Monarchy', The Historical Journal, 40:4 (December 1997), p. 908.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), pp. 71–73.

- ^ David Loades, Mary Tudor (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989), pp. 210, 216.

- ^ Vertot, Ambassades, 3 (Leyden, 1763), 206, 237.

- ^ C. S. Knighton, Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the reign of Mary I (London, 1998), p. 57 no. 117: James E. Nightingale, 'Some Notice of William Herbert', Wiltshire Archeological and Natural History Magazine, 18 (Devizes, 1879), pp. 108–109: Patrick Fraser Tytler, England Under the Reigns of Edward VI and Mary, vol. 2 (London, 1839), pp. 419–420: Rawdon Brown, Calendar State Papers Venice, vol. 5 (London, 1873), pp. 516 no. 904, 520 no. 915.

- ^ David Loades, Mary Tudor (Basil Blackwell, 1989), p. 221: Rayne Allinson & Geoffrey Parker, 'A King and Two Queens', Helen Hackett, Early Modern Exchanges: Dialogues Between Nations and Cultures (Ashgate, 2015), p. 99.

- ^ Mary Jean Stone, History of Mary I, Queen of England (London, 1901), pp. 312–313

- ^ Sarah Duncan, Mary I: Gender, Power, and Ceremony in the Reign of England's First Queen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 64.

- ^ 'Marriage of Philip II and Mary', Bentley's Miscellany, 22 (London, 1847), p. 466.

- ^ George Oliver, History of the City of Exeter (Exeter 1861), p. 102.

- ^ 'Marriage of Philip II and Mary', Bentley's Miscellany, 22 (London, 1847), p. 467.

- ^ Martin A. S. Hume, 'The Visit of Philip II', The English Historical Review, 7:26 (April 1892), pp. 264–265.

- ^ C. S. Knighton & David Loades, Navy of Edward VI and Mary I (Navy Records Society, 2011), pp. 276, 436, 440–441.

- ^ Abbé de Vertot, Ambassades de Messieurs de Noailles en Angleterre, vol. 3 (Leyden, 1763), p. 262.

- ^ William Henry Black, Illustrations of Ancient State and Chivalry from MSS in the Ashmolean Museum (London: Roxburghe Club, 1839), pp. 44–46.

- ^ HMC 13th Report Part II, Portland, vol. 2 (London, 1893), p. 10.

- ^ Judith M. Richards, 'Mary Tudor as Sole Quene?: Gendering Tudor Monarchy', The Historical Journal, 40:4 (December 1997), p. 909.

- ^ Mary Jean Stone, History of Mary I, Queen of England (London, 1901), p. 321: Henry Ellis, New Chronicles of England and France, in Two Parts; by Robert Fabyan (London, 1811), p. 715: Ambassades de messieurs de Noailles en Angleterre, vol. 3 (Leyden, 1763), p. 286.

- ^ Martin A. S. Hume, 'The Visit of Philip II', The English Historical Review, 7:26 (April 1892), p. 267.

- ^ Sarah Duncan, Mary I: Gender, Power, and Ceremony in the Reign of England's First Queen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 78–79.

- ^ John Strype, Ecclesiastical Memorials, Queen Mary, vol. 3 (London, 1721), pp. 127–128: John Gough Nichols, The Chronicle of Queen Jane (London: Camden Society, 1850), p. 77: Diary of Henry Machyn (London, 1848), p. 66: William Douglas Hamilton, A Chronicle of England by Charles Wriothesley (London, 1877), p. 118: Charles Lethbridge Kingsford, Camden Miscellany XII: Two London Chronicles from the Collections of John Stow (London, 1910), p. 37

- ^ William Henry Black, llustrations of Ancient State and Chivalry (London, 1840), pp. 46–49: Calendar State Papers Foreign Mary (London, 1861), p. 107 no. 241.

- ^ Samson (2020), p. 105: Hilton (1938), p. 49.

- ^ Hilton (1968), pp. 46–47: Chronicle of Queen Jane (London, 1850), p. 135.

- ^ John Gough Nichols, Chronicle of Queen Jane (London: Camden Society, p. 134.

- ^ Eleri Lynn, Tudor Textiles (Yale, 2020), pp. 75–76.

- ^ Fiona Kisby, 'Religious Ceremonial at the Tudor Court', Religion, Politics, and Society in Sixteenth-Century England (Cambridge, 2003), p. 7.

- ^ Judith M. Richards, 'Mary Tudor as Sole Quene?: Gendering Tudor Monarchy', The Historical Journal, 40:4 (December 1997), p. 910.

- ^ John Gough Nichols, The Chronicle of Queen Jane (London: Camden Society, 1850), p. 136.

- ^ Henry Ellis, New Chronicles of England and France, in Two Parts; by Robert Fabyan (London, 1811), pp. 715–717.

- ^ Corinna Streckfuss, 'Spes maxima nostra: European propaganda and the Spanish match', Alice Hunt & Anna Whitelock, Tudor Queenship (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), pp. 146, 152, 251–252: Johanna C. E. Strong, 'Happily Ever After? Elizabethan Representations of Mary I and Philip II's Marriage', Valerie Schutte & Jessica S. Hower, Mary I in Writing: Letters, Literature, and Representation (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), pp. 221–245.

- ^ Hilton (1938), p. 50.

- ^ Bentley's Miscellany, 22, p. 464: Himsworth (1962), p. 97.

- ^ John Gough Nichols, The Chronicle of Queen Jane (London: Camden Society, 1850), p. 140: Ducie, p. 723: Bentley's Miscellany, 22, p. 466.

- ^ David Loades, Mary Tudor: A Life (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989), p. 225.

- ^ Teofilo F. Ruiz, A King Travels: Festive Traditions in Late Medieval and Early Modern Spain (Princeton, 2012), p. 1.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), pp. 107–108, citing Andrés Muñoz, Viaje de Felipe II a Inglaterra (Zaragoza, 1554): Ducie, 'Expedition of Philip II to England', The Fortnightly, 25/31 (London, 1879), pp. 723, 726.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), p. 108.

- ^ Himsworth (1962), p. 91: Alison J. Carter, 'Mary Tudor's Wardrobe', Costume, 18 (1984), p. 28.

- ^ llustrations of Ancient State and Chivalry (London, 1840), p. 50.

- ^ Ducie (1879), pp. 723–724: Himsworth (1962), p. 84.

- ^ Himsworth (1962), p. 91.

- ^ John Gough Nichols, The Chronicle of Queen Jane (London: Camden Society, 1850), p. 140: New Chronicles of England and France, in Two Parts; by Robert Fabyan (London, 1811), p. 715.

- ^ Gachard & Piot, Collection des voyages des souverains des Pays-Bas, 4 (Bruxelles, 1881), p. 17

- ^ Mary Jean Stone, History of Mary I, Queen of England (London, 1901), p. 326: Darcy Kern, 'Mary I as Mediterranean Queen', Valerie Schutte & Jessica S. Hower, Writing Mary I: History, Historiography, and Fiction (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), pp. 93–94: Judith M. Richards, 'Mary Tudor as Sole Quene?: Gendering Tudor Monarchy', The Historical Journal, 40:4 (December 1997), p. 911.

- ^ Sarah Duncan, Mary I: Gender, Power, and Ceremony in the Reign of England's First Queen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 81.

- ^ Sarah Duncan, Mary I: Gender, Power, and Ceremony in the Reign of England's First Queen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 82: Judith M. Richards, 'Mary Tudor as Sole Quene?: Gendering Tudor Monarchy', The Historical Journal, 40:4 (December 1997), pp. 911–912.

- ^ Sarah Duncan, Mary I: Gender, Power, and Ceremony in the Reign of England's First Queen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 83.

- ^ John Gough Nichols, The Chronicle of Queen Jane (London: Camden Society, 1850), p. 141: William Douglas Hamilton, A Chronicle of England by Charles Wriothesley (London, 1877), p. 121.

- ^ David Loades, Mary Tudor: A Life (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989), p. 226.

- ^ Agnes Strickland, Lives of the Queens of England, vol. 3 (London, 1864), pp. 101–102.

- ^ John Gough Nichols, The legend of Sir Nicholas Throckmorton, or Throckmorton's Ghost (London, 1874), p. 36, verse 141.

- ^ Maria Hayward, 'Dressed to Impress', Alice Hunt & Anna Whitelock, Tudor Queenship: The Reigns of Mary and Elizabeth (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), pp. 84–85: Maria Hayward, Dress at the court of Henry VIII (Maney, 2007), p. 52: Janet Arnold, Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd (Maney, 1993), p. 254: Alison J. Carter, 'Mary Tudor's Wardrobe', Costume, 18 (1984), p. 16.

- ^ HMC Salisbury Hatfield, vol. 10 (Dublin, 1906), pp. 356–357

- ^ Abbé de Vertot, Ambassades de Messieurs de Noailles en Angleterre, vol. 3 (Leyden, 1763), p. 290.

- ^ Abbé de Vertot, Ambassades de Messieurs de Noailles en Angleterre, vol. 2 (Leyden, 1763), p. 104.

- ^ Janet Arnold, Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd (Maney, 1988), pp. 55, 113.

- ^ Alexander Samson, 'Changing Places: The Marriage and Royal Entry of Philip, Prince of Austria, and Mary Tudor, July–August 1554', Sixteenth Century Journal, 36:3 (Fall 2005), p. 764: Rawdon Brown, Calendar State Papers Venice, vol. 5 (London, 1873), pp. 533, 544, no. 934: Hilary Doda, 'Lady Mary to Queen of England: Transformation, Ritual, and the Wardrobe of the Robes', Sarah Duncan & Valerie Schutte, The Birth of a Queen: Essay on the Quincentenary of Mary I (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), p. 51: Alison J. Carter, 'Mary Tudor's Wardrobe', Costume, 18 (1984), p. 15.

- ^ Viaje de Felipe Segundo á Inglaterra (Madrid, 1877), p. 77: M. Channing Linthicum, Costume in the Drama of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries (Oxford, 1936), p. 272.

- ^ Frederick Madden, Privy Purse Expenses of the Princess Mary (London, 1831), p. cxliii, citing Guido Raviglio Rosso, Historia Delle Cose Occorse Nel Regno D'Inghilterra (Venice, 1558), p. 68: Hilary Doda, 'Lady Mary to Queen of England: Transformation, Ritual, and the Wardrobe of the Robes', Sarah Duncan & Valerie Schutte, The Birth of a Queen: Essay on the Quincentenary of Mary I (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), pp. 49–66.

- ^ Corinna Streckfuss, 'Spes maxima nostra: European propaganda and the Spanish match', Alice Hunt & Anna Whitelock, Tudor Queenship (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), p. 148.

- ^ Il trionfo delle superbe nozze fatte nel sposalitio del principe di il Spagna, British Library Festival Books

- ^ Alison J. Carter, 'Mary Tudor's Wardrobe', Costume, 18 (1984), p. 16.

- ^ Viaje de Felipe segundo á Inglaterra, por Andrés Muñoz (Madrid, 1877), p. 74.

- ^ Karen Hearn, Dynasties (London, 1995), pp. 66–67: Roy Strong, Tudor and Jacobean Portraits, vol. 1 (London, 1969), p. 212: Martin A. S. Hume, 'The Visit of Philip II', The English Historical Review, 7:26 (April 1892), p. 262.

- ^ Maureen Quilligan, When Women Ruled the World: Making the Renaissance in Europe (Liveright, 2021): Fiona Lindsay Shen, Pearl: Nature's Perfect Gem (London: Reaktion Books, 2022), p. 242.

- ^ Corinna Streckfuss, 'Spes maxima nostra: European propaganda and the Spanish match', Alice Hunt & Anna Whitelock, Tudor Queenship (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), p. 148.

- ^ Frederick Madden, Privy Purse Expenses of Princess Mary (London, 1831), p. cxcviii: Felicity Heal, The Power of Gifts: Gift-exchange in Early Modern England (Oxford, 2014), pp. 152–153.

- ^ Bentley's Miscellany, 22, p. 466: Colección de documentos inéditos para la historia de España, vol. 1 (Madrid, 1842), p. 573: Himsworth (1962), p. 99.

- ^ Patrick Fraser Tytler, England Under the Reigns of Edward VI and Mary, vol. 2 (London, 1839), p. 431.

- ^ Sarah Duncan, Mary I: Gender, Power, and Ceremony in the Reign of England's First Queen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 80-81: Alison J. Carter, 'Mary Tudor's Wardrobe', Costume, 18 (1984), p. 21.

- ^ Vertot, Ambassades, 3 (Leyden, 1763), p. 204.

- ^ Royall Tyler, Calendar of State Papers, Spain, 1554–1558, vol. 13 (London, 1954), no. 503 translated from Spanish.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), pp. 110–111: Patrick Fraser Tytler, England Under the Reigns of Edward VI. and Mary, vol. 2 (London, 1839), pp. 416, 431: Alexander Samson, 'Changing Places: The Marriage and Royal Entry of Philip, Prince of Austria, and Mary Tudor, July–August 1554', Sixteenth Century Journal, 36:3 (Fall 2005), p. 764 quoting Ocampo, Sucesos Acaesidos.

- ^ Alexander Samson, 'Changing Places: The Marriage and Royal Entry of Philip, Prince of Austria, and Mary Tudor, July–August 1554', Sixteenth Century Journal, 36:3 (Fall 2005), p. 765.

- ^ John Strype, Ecclesiastical Memorials, vol. 3 (London, 1721), p. 130.

- ^ Gachard & Piot, Collection des voyages des souverains des Pays-Bas, 4 (Bruxelles, 1881), p. 17.

- ^ Himsworth (1962), p. 99.

- ^ Hilton (1938), p. 58: Viaje (1877), p. 75.

- ^ Anne Somerset, Ladies-in-waiting : from the Tudors to the present day (Castle Books, 2004), p. 56: Himsworth (1962), p. 87: Martin A. S. Hume, 'The Visit of Philip II', The English Historical Review, 7:26 (April 1892), p. 274.

- ^ Alfred Pollard, Tudor Tracts (London, 1903), pp. 192–193

- ^ John Gough Nichols, Narratives of the Reformation (London: Camden Society, 1859), pp. 169–171: Stephen Hyde Cassan, The Lives of the Bishops of Winchester vol. 1 (London, 1827), p. 505.

- ^ David Loades, Mary Tudor: A Life (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989), p. 226.

- ^ John Gough Nichols, The Chronicle of Queen Jane (London: Camden Society, 1850), p. 170.

- ^ Mary Jean Stone, History of Mary I, Queen of England (London, 1901), p. 328

- ^ Sydney Anglo, Spectacle Pageantry, and Early Tudor Policy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), p. 325.

- ^ Bentley's Miscellany, 22, p. 467: Colección de documentos inéditos para la historia de España, vol. 1 (Madrid, 1842), p. 573: Himsworth (1962), pp. 87–88, 92, 99.

- ^ Himsworth (1962), pp. 87–88.

- ^ Jennifer Neville, Footprints of the Dance: An Early Seventeenth-Century Dance Master’s Notebook (Brill, 2018), pp. 49–50: Richard Hudson, The Allemande and the Tanz, vol. 1 (Cambridge, 1986), p. 53: Daniel Heartz, 'A Spanish Masque of Cupid', Musical Quarterly, vol. 49 (1963), p. 69.

- ^ Himsworth (1962), pp. 88, 93, 94.

- ^ Maria Hayward, 'Seat Furniture at the Court of Henry VIII', Dinah Eastop & Kathryn Gill, Upholstery Conservation: Principles and Practice (Butterworth, 2001), pp. 124, 128.

- ^ Elizabeth Lewis, 'A sixteenth century painted ceiling from Winchester College', Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club Archaeological Society 51 (1995), pp. 137–165

- ^ Anne Crone, Michael Bath, Michael Pearce, The dendrochronology and art history of a sample of 16th and 17th Century painted ceilings (Historic Environment Scotland, 2017), p. 27.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), pp. 112–113: The Chronicle of Queen Jane, p. 144.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), p. 110: Sarah Duncan, Mary I: Gender, Power, and Ceremony in the Reign of England's First Queen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 83.

- ^ Mitchell Gould, "Philip II of Spain: King, Consort, and Son", Aidan Norrie et al, Tudor and Stuart Consorts: Power, Influence, and Dynasty (palgrave Macmillan, 2022), p. 169.

- ^ Himsworth (1962), p. 93.

- ^ Himsworth (1962), pp. 94, 100.

- ^ Corinna Streckfuss, 'Spes maxima nostra: European propaganda and the Spanish match', Alice Hunt & Anna Whitelock, Tudor Queenship (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), p. 148.

- ^ David Loades, Mary Tudor (Basil Blackwell, 1989), p. 226.

- ^ Sarah Duncan, Mary I: Gender, Power, and Ceremony in the Reign of England's First Queen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 100.

- ^ William Douglas Hamilton, A Chronicle of England by Charles Wriothesley (London, 1877), p. 121.

- ^ John Strype, Ecclesiastical Memorials, vol. 3 (London, 1721), pp. 130–131: John Gough Nichols, The Chronicle of Queen Jane (London: Camden Society, 1850), pp. 77, 144–145: John Gough Nichols, Chronicle of the Grey Friars of London (London: Camden Society, 1852), p. 91.

- ^ Royall Tyler, Calendar State Papers Spain, 13 (London, 1954), pp. 443–444: Gachard & Piot, Collection des voyages des souverains des Pays-Bas, 4 (Bruxelles, 1881), pp. 15-20

- ^ Vertot, Ambassades des Noailles, 3, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Alexander Samson, 'Images of co-monarchy in the London entry of Philip and (1554)', Jean Andrews, Marie-France Wagner, Marie-Claude Canova Green, Writing Royal Entries in Early Modern Europe (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013), pp. 113–128.

- ^ Mary Jean Stone, History of Mary I, Queen of England (London, 1901), p. 330

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), pp. 126–127.

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), pp. 122–128: Alexander Samson, 'Images of co-monarchy in the London entry of Philip and Mary, 1554', Jean Andrews, Marie-France Wagner, Marie-Claude Canova-Green, Writing Royal Entries in Early Modern Europe (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013), pp. 113–128.

- ^ William Henry Black, Illustrations of Ancient State and Chivalry from MSS in the Ashmolean Museum (London, 1840), pp. 64–65.

- ^ C. S. Knighton, Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the reign of Mary I (London, 1998), p. 59 no. 122: Patrick Fraser Tytler, England Under the Reigns of Edward VI and Mary, vol. 2 (London, 1839), pp. 433–434.

- ^ Retha M. Warnicke, The Marrying of Anne of Cleves: Royal Protocol in Early Modern England (Cambridge, 2000), p. 253: The 19th-century biographer Agnes Strickland asserted that Anne of Cleves last saw Mary at her coronation, Lives of the Queens of England, vol. 2 (London, 1864), p. 330, cited by Valerie Schutte, 'Anne of Cleves: Survivor Queen', Aidan Norrie, Tudor and Stuart Consorts: Power, Influence, and Dynasty (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), p. 116.

- ^ Sydney Anglo, Spectacle Pageantry and Early Tudor Policy (Oxford, 1969). pp. 334–335.

- ^ Viaje de Felipe segundo á Inglaterra, por Andrés Muñoz (Madrid, 1877), p. 80: Hilton (1938), p. 59.

- ^ David Loades, Mary Tudor: A Life (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989), p. 232.

- ^ Charles Lethbridge, Two London chronicles from the collections of John Stow (London: Camden Society, 1910), p. 38

- ^ Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester, 2020), p. 173: Glyn Redworth, 'Philip I of England, embezzlement, and the quantity theory of money', Economic History Review, 55 (2002), pp. 248–261.

- ^ David Loades, Intrigue and Treason: The Tudor Court, 1547-1558 (Pearson, 2004), p. 191: David Sánchez Cano, 'Entertainments in Madrid', Alexander Samson, The Spanish Match: Prince Charles's Journey to Madrid, 1623 (Ashgate, 2006), p. 61: Charles Lethbridge, Two London chronicles from the collections of John Stow (London: Camden Society, 1910), pp. 39–40.

External links and sources

edit- Mary Tudor and her wedding, video: Winchester Cathedral learning team

- Gonzalo Velasco Berenguer, 'When England had a Spanish king, and what that tells us about Camilla’s title', The Conversation, 23 April 2023

- Sheila Himsworth, 'Marriage of Philip II of Spain with Mary Tudor', Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club, 22:2 (1962), pp. 82–100, three primary sources

- Ronald Hilton, 'Marriage of Queen Mary and Philip of Spain', Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club, 14:1 (1938), pp. 46–62

- Elizabeth Lewis, 'A Sixteenth Century Painted Ceiling from Winchester College', Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club, 51 (1995/6), pp. 137–165

- Earl of Ducie, 'Expedition of Philip II to England', The Fortnightly Review, 25/31 (London, 1879), pp. 718–734, English commentary on the Muñoz account

- Andrés Muñoz, Viaje de Felipe Segundo á Inglaterra (Madrid, 1877), the Muñoz account

- 'Marriage of Philip and Mary', Bentley's Miscellany, 22 (1847), pp. 459–468, includes a translation of the account by Juan de Varaona or Barahona

- Juan de Varaona, or Barahona, 'Viaje de Felipe II', Colección de documentos inéditos para la historia de España, vol. 1 (Madrid, 1842), pp. 564–574

- Il trionfo delle superbe Nozze fatte nel Sposalitio del Principe di il Spagna & la Regina d'Inghilterra, British Library Festival Books

- Thomas Hearne, De rebus Britannicis collectanea, vol. 4 (London, 1774), pp. 398–400 'Marriage of Queene Marye unto Phillip Prince of Spayne'.

- Fragment of a Latin wardrobe account of Mary, BnF Gallica Anglais 176

- Bethany Pleydell, "The Spanish Tudors: Fashioning the Anglo-Spanish Elite through Dress, c.1553-1603, and beyond", PhD thesis, University of Bristol, 2019