This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The welfare state of the United Kingdom began to evolve in the 1900s and early 1910s, and comprises expenditures by the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland intended to improve health, education, employment and social security. The British system has been classified as a liberal welfare state system.[1]

History

editBefore the official establishment of the modern welfare state, clear examples of social welfare existed to help the poor and vulnerable within British society. A key date in the welfare state's history is 1563; when Queen Elizabeth I's government encouraged the wealthier members of society to give to the poor,[2] by passing the Poor Act 1562.

The welfare state in the modern sense was anticipated by the Royal Commission into the Operation of the Poor Laws 1832 which found that the Poor Relief Act 1601 (a part of the English Poor laws) was subject to widespread abuse and promoted squalor, idleness and criminality in its recipients, compared to those who received private charity. Accordingly, the qualifications for receiving aid were tightened up, forcing many recipients to either turn to private charity or accept employment.

Opinions began to be changed late in the century by reports drawn up by men such as Seebohm Rowntree and Charles Booth into the levels of poverty in Britain. These reports indicated that in the massive industrial cities, between one-quarter and one-third of the population were living below the poverty line.

A 2022 study linked trade shocks during the first globalization (1870–1914) with increased support for a welfare state and reduced support for the Conservative Party.[3]

Liberal reforms

edit

The late nineteenth century saw the emergence of New Liberalism within the Liberal Party, which advocated state intervention as a means of guaranteeing freedom and removing obstacles to it such as poverty and unemployment. The policies of the New Liberalism are now known as social liberalism.[4]

The New Liberals included intellectuals like L. T. Hobhouse, and John A. Hobson. They saw individual liberty as something achievable only under favourable social and economic circumstances.[5] In their view, the poverty, squalor, and ignorance in which many people lived made it impossible for freedom and individuality to flourish. New Liberals believed that these conditions could be ameliorated only through collective action coordinated by a strong, welfare-oriented, and interventionist state.[6]

After the historic 1906 victory, the Liberal Party launched the welfare state with a series of major welfare reforms in 1906–1914.[7] The reforms were greatly extended over the next forty years.[7] The Liberal Party introduced multiple reforms on a range of issues, including health insurance, unemployment insurance, and pensions for elderly workers, thereby laying the groundwork for the future British welfare state. Some proposals failed, such as licensing fewer pubs, or rolling back Conservative educational policies. The People's Budget of 1909, championed by David Lloyd George and fellow Liberal Winston Churchill, introduced unprecedented taxes on the wealthy in Britain and radical social welfare programmes to the country's policies.[8] In the Liberal camp, as noted by one study, "the Budget was on the whole enthusiastically received."[9] It was the first budget with the expressed intent of redistributing wealth among the public. It imposed increased taxes on luxuries, liquor, tobacco, high incomes, and land – taxation that fell heavily on the rich. The new money was to be made available for new welfare programmes as well as new battleships. In 1911 Lloyd George succeeded in putting through Parliament his National Insurance Act, making provision for sickness and invalidism, and this was followed by his Unemployment Insurance Act.[10]

The minimum wage was introduced in Great Britain in 1909 for certain low-wage industries and expanded to numerous industries, including farm labour, by 1920. However, by the 1920s, a new perspective was offered by reformers to emphasise the usefulness of family allowance targeted at low-income families was the alternative to relieving poverty without distorting the labour market.[11][12] The trade unions and the Labour Party adopted this view. In 1945, family allowances were introduced; minimum wages faded from view.[citation needed]

The experience of almost total state control during the Second World War had encouraged the belief that the state might be able to solve problems in wide areas of national life.[13]

The Liberal government of 1906–1914 implemented welfare policies concerning three main groups in society: the old, the young and working people.[7]

| Young | Old | Working |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Beveridge Report and Labour

editThe aftermath of the First World War boosted demands for social reform, and led to a permanent increase in the role of the state in British society. The end of the war also brought a period of unemployment and poverty, particularly in northern industrial towns, that deepened into the Great Depression by the 1930s.[13]

During the war, the government became much more involved in people's lives via governmental organisation of the rationing of foodstuffs, clothing and fuel and extra milk and meals being given to expectant mothers and children.[13] The wartime coalition, and the introduction of family allowances.[19] Many people welcomed this government intervention and wanted it to go further.[13]

The Beveridge Report of 1942, (which identified five "Giant Evils" in society: squalor, ignorance, want, idleness and disease) essentially recommended a national, compulsory, flat rate insurance scheme which would combine unemployment, widows benefit, child benefit and retirement benefits into one central government support scheme. In regards to healthcare Beveridge preferred the contemporary healthcare system of voluntary and private hospitals "more than that of a taxpayer funded healthcare"[20] believing more people would access healthcare when they need it if they were voluntarily involved in their own healthcare. But it is key to note Beveridge still emphasised that healthcare should be accessible for everyone in the United Kingdom and that people should give what they can according to their means when receiving healthcare in voluntary hospitals. Beveridge himself was careful to emphasise that unemployment benefits should be held to a subsistence level, and after six months would be conditional on work or training, so as not to encourage abuse of the system.[21] That was however predicated on the concept of the "maintenance of employment" which meant 'it should be possible to make unemployment of any individual for more than 26 weeks continuously a rare thing in normal times' [21] and recognised that the imposition of a training condition would be impractical if the unemployed were numbered by the million.[21] After its victory in the 1945 general election, the Labour Party pledged to eradicate the Giant Evils, and undertook policy measures to provide for the people of the United Kingdom "from the cradle to the grave." While the original intention of the report was to abolish these Giant Evils, the implementation of these suggested policies aimed to reduce income, health, and educational inequalities.[22] However, the lack of real follow-through on Beveridge's recommended strategies meant that the Labour government ultimately failed to abolish poverty with their welfare reforms.[22]

Included among the laws passed were the National Assistance Act 1948 (11 & 12 Geo. 6. c. 29), National Insurance Act 1946, and National Insurance (Industrial Injuries) Act 1946.

Impact

editThis policy resulted in increased expenditure and a widening of what was considered to be the state's responsibility. In addition to the central services of education, health, unemployment and sickness allowances, the welfare state also included the idea of increasing redistributive taxation, and increasing regulation of industry, food, and housing (better safety regulations, weights and measures controls, etc.)

The foundation of the National Health Service (NHS) did not involve building new hospitals, but nationalisation of existing municipal provision and charitable foundations. The aim was not to substantially increase provision but to standardise care across the country; indeed William Beveridge believed that the overall cost of medical care would decrease, as people became healthier and so needed less treatment.

However, instead of falling, the cost of the NHS has risen by 4% annually on average due to an ageing population,[23] leading to a reduction in provision. Charges for dentures, and spectacles were introduced in 1951 by the same Labour government that had founded the NHS three years earlier, and prescription charges by the successive Conservative Government were introduced in 1952.[24] In 1988, free eye tests for all were abolished, although they are now free for the over-60s.[25]

After 1979, Margaret Thatcher had laid the post-war Keynesian consensus to rest, in favour of an Individualist and Monetarist Welfare policy, guided by the economy. This Thatcherite consensus was characterised by policies such as Privatisation, driven by her belief in Individualism and Competition.[26] Therefore, her main focus was to attempt to control public spending, privatisation, targeting and rising inequality, so much of the 1980s was focused on cutting public spending in the UK.

Policies differ in different regions of the United Kingdom, but the provision of a welfare state is still a basic principle of government policy in the United Kingdom today. The principle of health care "free at the point of use" became a central idea of the welfare state, which later Conservative governments, although critical of some aspects of the welfare state, did not reverse.

Welfare spending on poor people dropped by 25% under the United Kingdom government austerity programme, cuts to benefits that disabled people receive were significant, Personal Independence Payments and Employment and Support Allowance have both dropped by 10%. Over half of families living below the breadline have at least one relative with a disability. Cuts include, tax credits (£4.6bn), universal credit (£3.6bn), child benefit (£3.4bn), disability benefits (£2.8bn), Employment and Support Allowance and Incapacity Benefit (£2bn) and housing benefit (£2.3bn). Frank Field said, "A £37bn attack has been mounted on the living standards of many of our fellow citizens to such an extent that possibly millions struggle to keep on top of their rent, pay the bills and buy adequate food. Likewise, an unknown number are unable to clothe their children properly before sending them to school where all too many of these children not only rely on free school dinners as a cornerstone of their diet, but on breakfast and supper clubs as well."[27]

Expenditure

editIn the financial year 2014/15, state pensions were overwhelmingly the largest governmental welfare expense, costing £86,500,000,000 followed by housing benefit, which accounted for over £20,000,000,000[28] Expenditure in 2015–16 on benefits included: £2,300,000,000 paid to unemployed people and £27,100,000,000 to people on low incomes, and £27,600,000,000 for personal tax credits.[29][30]

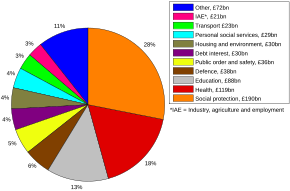

UK Government welfare expenditure 2011–12 (percent)

In 2023/24, it is expected that government health spending, which is the biggest element of public spending, will reach £176,200,000,000.[31] Other welfare expenses include education, which is predicted to reached £81,400,000,000, and state pensions, for which expenditure will be £124,300,000,000.[31]

| Benefit | Expenditure (£bn) |

|---|---|

| State pension | 86.5 |

| Tax credits (Working tax credits and Child tax credits) | 29.7 |

| Housing Benefit | 23.5 |

| Disability Living Allowance | 15.4 |

| Incapacity benefits | 14.1 |

| Child benefit | 11.6 |

| Pension Credit | 6.6 |

| Attendance Allowance | 5.4 |

| Jobseeker's Allowance | 3.1 |

| Income Support | 2.6 |

| Maternity and paternity pay | 2.4 |

| Carer's Allowance | 2.3 |

| Winter fuel payments | 2.1 |

| War pensions | 0.8 |

| Universal Credit | 0.1 |

| Other | 5.9 |

| Total | 213.9 |

Criticisms

editIn the grammar of British social attitudes, an entitlement is something I get, a benefit is something you get, a handout is something they get, and taxpayers’ hard-earned money is something asylum seekers get.

Conservative thinkers have debated the structural incompatibility between liberal principles and welfare state principles. Certain sectors of society have argued that the welfare state creates a disincentive for working and investment.[33][34] Also suggesting that the welfare state at times does not eliminate the causes of individual contingencies and needs.[35] Economically, the net losers of the welfare state are often more against its values and role within society.[36]

In 2010, the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition government led by David Cameron argued for a reduction of welfare spending in the United Kingdom as part of their programme of austerity.[37] Government ministers have argued that a growing culture of welfare dependency is perpetuating welfare spending, and claim that a cultural change is required to reduce the welfare bill.[38] Public opinion in the UK appears to support a reduction in welfare spending, however commentators have suggested that negative public perceptions are founded on exaggerated assumptions about the proportion of spending on unemployment benefit and the level of benefit fraud.[39][40]

Figures from the Department for Work and Pensions show that benefit fraud is thought to have cost taxpayers £1.2 billion during 2012–13, up 9% on the year before.[41] This was lower than the £1.5 billion of benefit underpayment due to error.[42][needs update]

In some cases, relatives who bring up a child when the parents cannot bring up the child face sanctions and financial penalties, they can be left poor and homeless.[43] There are also widespread complaints from church groups and others that the UK welfare state does insufficient work to prevent poverty, deprivation and even hunger.[44] In 2018, food bank usage in the UK reached its highest point on record, with the UK's main food bank provider, The Trussell Trust, stating that welfare benefits do not cover basic living costs. The Trussell Trust's figures showed that 1,332,952 three-day emergency food supplies were delivered to people from March 2017 to March 2018. This represented a 13% increase from the previous year.[45]

In 2018 support for raising taxes to finance more provision on health, education and social benefits was the highest it had been since 2002 according to NatCen Social Research. Two-thirds of Labour supporters favoured tax rises and 53% of Conservatives also favoured that.[46]

In 2018 the House of Commons library estimated that by 2021, £37bn less would be spent on working-age social security than in 2010. Cuts to disability benefits, Personal Independence Payments (PIP) and employment and support allowance (ESA) are noteworthy, they will have fallen by 10%, since 2010. Over half of families with income below the breadline include at least one person with a disability. There are also cuts to tax credits Universal Credit child benefit disability benefits ESA and incapacity benefit and housing benefit. Alison Garnham of the Child Poverty Action Group said, "Cuts and freezes have taken family budgets to the bone as costs rise and there is more pain to come as the two-child limit for tax credits and universal credit, the bedroom tax, the benefit cap and the rollout of universal credit push families deeper into poverty."[27]

Social security payments in 2019 were the lowest they had been since the welfare state was started and food bank use had increased. The Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) found £73 per week, (which is standard for Universal Credit that 2.3 million people claim) amounted to 12.5% of median earnings. When unemployment benefit was introduced in 1948 it amounted to 20%. Millions of people in 2019 were "excluded from mainstream society, with the basic goods and amenities needed to survive let alone thrive increasingly out of their grip". The IPPR urged all parties to add an emergency £8.4bn into the welfare system, which has become harder than previous systems because debt deductions are made from payments, there is increasing underpayment and strict sanctions are applied. One in three universal credit claimants are working.[47]

Numerous negative consequences have been attributed to benefit sanctions imposed by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), the UK Government department that runs the welfare state in the UK. These include "increased debt and rent arrears, food poverty, crime and worsening physical and mental health.[48] Statistics indicate that in the period of 2011 to 2015 benefit sanctions on people with mental health problems increased by 668%. 19,259 people with mental health problems had benefits stopped in the period of 2014 to 2015, compared to 2,507 people in the period of 2011 to 2012.[49] In 2020, the UK Government admitted that it had made no assessment of the impact that benefit sanctions made on mental health.[50] At the same point in time the Government also refused to assess the impact benefit sanctions have on people's mental health, which came after repeated warnings on the long-term damage they can cause to people that use the welfare state and to these people's families.[51] Also in 2020, it was reported that at least 69 suicides were linked to the DWP's handling of benefit claims. The National Audit Office (NAO) said the actual number of deaths linked to claims could be much higher than this. It was also reported that the DWP were not looking into information from coroners or families, nor investigating all the reports of suicide made aware to it.[52] In the same year the DWP were accused of a "cover-up" due to destroying approximately 50 reports connected to benefits being stopped. Officials blamed data protection laws for the actions, though the data watchdog denied there was any requirement to destroy the documents by any date.[53] In March 2022, an academic study into whether benefit sanctions are linked to claimant ill-health, including mental illness and suicide was stopped after the DWP and Government ministers refused to release their recorded data on sanctions.[54] From a contemporary perspective, in practice, social welfare in the United Kingdom is very different from the ideal version of the welfare state that people may carry. Coverage is extensive, but benefits and services are delivered at a low level. The social protection provided is patchy, and services are tightly rationed." This opinion appears to be growing in popularity amongst the general population of the UK. This argument does stand when you compare certain statistics with some of Europe's biggest nations. The UK has a tax revenue, as a share of GDP percentage of 12.55%... this is in this is simply incomparable when matched with France's (57%), Germany's (66.66%), and Italy's (75%). It was also found, in a 2021 study by The Health Foundation, that Britain spends the 6th most money on health care amongst "developed countries." This figure sits below the EU average and explains why some believe the welfare state is not so successful. It is also a fact that "The UK dedicates roughly one-fifth of its GDP to social spending. That places us 17th – roughly in the middle – of OECD countries" (Whiteford, 2022).[55]

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, it became clear that there was a distinct shortage of provisions available to support public health, including a lack of beds in the NHS and a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE). In the closing statement of the British Medical Association (BMA) in July 2023, it was noted that this lack of pandemic preparedness manifested in four key areas; failure to protect healthcare workers, lack of capacity and resources, failings of the test and trace system, and failings in government structures and processes.[56] The statement also claimed that the "UK was bottom of the table on numbers of doctors, nurses, beds, intensive care units, respirators and ventilators",[56] and that funding of healthcare has been inadequate since 2010,[56] suggesting that the state the NHS found itself in at the outbreak of the pandemic had not been an overnight shift, but rather the effect of the past decade's funding issues.

The UK has seen a drastic increase in the usage of foodbanks nationwide: 2.17m food bank users in 2021/22 in comparison to the 41,000 in 2009/10.[57] During the COVID-19 crisis, food insecurity impacted 16% of the population, and some critics argue that government food aid was instigated too late for the elderly and vulnerable.[citation needed] There have also been criticisms of the food parcels given, as reports stated that the parcels lacked nutritional food and instead contained an abundance of processed foods.[citation needed]

Historical statistics on welfare trends

editThis section needs to be updated. The reason given is: seems to run from 1948 to the late 70s – ideally should run to the present day, and in single sequences. (June 2024) |

Benefit rates as a percentage of industrial earnings

edit| Year (month) | Single pension | Supplementary Benefit for single person | Family Allowance for four children |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 (October) | 18.9 | 17.5 | 10.9 |

| 1961 (April) | 19.1 | 17.8 | 9.3 |

| 1962 (April) | 18.4 | 17.1 | 8.9 |

| 1963 (May) | 20.8 | 19.5 | 8.6 |

| 1964 (April) | 19.2 | 18.1 | 8.0 |

| 1964 (October) | 18.7 | 17.6 | 7.7 |

| 1965 (April) | 21.2 | 20.1 | 7.4 |

| 1965 (October) | 20.4 | 19.4 | 7.1 |

| 1966 (April) | 19.8 | 18.8 | 6.9 |

| 1966 (October) | 19.7 | 20.0 | 6.9 |

| 1967 (April) | 19.4 | 19.7 | 6.8 |

| 1967 (October) | 21.0 | 20.1 | 7.7 |

| 1968 (April) | 20.2 | 19.3 | 11.9 |

| 1968 (October) | 19.6 | 19.8 | 12.6 |

| 1969 (April) | 18.8 | 19.3 | 12.1 |

| 1969 (November) | 20.0 | 19.2 | 11.7 |

| 1970 (April) | 19.0 | 18.3 | 11.3 |

| 1970 (November) | 17.6 | 18.3 | 10.2 |

| 1971 (March) (est.) | 17.3 | 18.0 | 10.0 |

Note on source, as quoted in the text: "based on statistics of weekly earnings, Employment and Productivity Gazette."

Changes in National Assistance/Supplementary Benefit

edit| Date of change | Real value single pensioner | Real value married man with three children (b) | Real take home pay for average worker |

|---|---|---|---|

| May 1963 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| March 1965 | 111 | 112 | 106 |

| November 1966 | 117 | 110 | 106 |

| October 1967 | 122 | 115 | 108 |

| November 1969 | 122 | 115 | 110 |

- Notes

- (a) As quoted in the text: "the scale is calculated using the average discretionary addition (adjusted to spread winter fuel costs throughout the year) for retirement pensioners. It does not include any allowance for rent. The price index used for the single pensioner is that in the Employment and Productivity Gazette."

- (b) As quoted in the text: "it is assumed that the children are aged four, six, and eleven."

Increases in National Insurance benefits

edit| Date of increase | Real take home pay for average worker (a) | Real value of single pension (b) | Real value of unemployment benefit (man with wife and three children) (c) |

|---|---|---|---|

| March/May 1963 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| January/March 1965 | 106 | 111 | 110 |

| October 1967 | 108 | 114 | 113 |

| November 1969 | 110 | 114 | 116 |

- Notes

- (a) As quoted by text: "Based on average earnings for adult male manual workers in manufacturing, allowing for income tax and national insurance contributions."

- (b) As quoted by text: "Calculated on the special price index for single pensioner households published by the Employment and Productivity Gazette adjusted for housing expenditure using the housing component of the retail price index. Since a disproportionate number of pensioners have controlled tenancies, this may overstate the increase in prices."

- (c) This column is deflated by use of the Retail Price Index

Social security benefits as a percentage of average earnings

edit| Government | Sickness/unemployment benefit a | a plus earnings related supplement | Retirement pensions c | Supplementary allowance/benefits d | Family allowance/child benefit e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour (1951) | 25.7 | 25.7 | 30.4 | 30.4 | 8.0 | |

| Conservative (1963) | 33.8 | 33.8 | 33.0 | 31.6 | 5.3 | |

| Labour (1969) | 32.4 | 52.3 | 32.4 | 31.4 | 3.8 | |

| Conservative (1973) | 29.1 | 46.2 | 30.5 | 28.5 | 3.0 | |

| Labour (1978) | 30.5 | 44.4 | 37.4 | 30.2 | 3.7 | |

- a,b Man plus dependent wife.

- c Man plus dependent wife on his insurance.

- d Married couple.

- e For one child.

Social policy benefits and earnings under the Labour Government 1964–69

edit| Year | Unemployment, sickness, and retirement benefits (single) | Retirement pension (married) | National assistance/supplementary benefit (married couple) | Adult male manual workers (weekly earnings) | Adult male administrative, technical, and clerical employees (weekly earnings) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 1969 | 148 | 149 | 150 | 154 | 148 |

Supplementary benefits rates as a proportion of income

edit| Year | End of year (a) | |

|---|---|---|

| As % of gross average earnings | ||

| Ordinary rate | Long term rate | |

| 1973 | 28.5 | 31.4 |

| 1974 | 28.1 | 33.6 |

| 1975 | 29.8 | 36.2 |

| 1976 | 30.8 | 37.1 |

| 1977 | 32.3 | 38.9 |

| 1978 | 30.6 | 37.8 |

| As % of net income (b) at average earnings | ||

| Ordinary rate | Long term rate | |

| 1973 | 37.9 | 41.8 |

| 1974 | 38.8 | 46.5 |

| 1975 | 42.4 | 51.5 |

| 1976 | 43.9 | 52.9 |

| 1977 | 44.1 | 53.1 |

| 1978 | 41.6 | 51.4 |

| Date of introduction | Single | Married couple |

|---|---|---|

| 1973 | 14.0 | 10.3 |

| 1974 | 23.8 | 19.8 |

| 1975 (April) | 25.0 | 20.4 |

| 1975 (November) | 25.7 | 21.4 |

| 1976 | 23.6 | 20.3 |

| 1977 | 23.4 | 20.4 |

| 1978 | 28.0 | 23.5 |

Households dependent on Supplementary Benefit

edit| Year | Pensioners | Under pensionable age family head or single parent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (as % of total) | Unemployed | Normally in full-time work | Sick or disabled | Others | ||

| 1974 | 2,680 | (52%) | 450 | 360 | 480 | 1,170 |

| 1976 | 2,800 | (44%) | 1,080 | 890 | 280 | 1,300 |

Changes in real terms in social security benefits

edit| Year | Supplementary benefits (a) | Sickness/unemployment benefit (b) | Retirement pensions (c) | Family allowance/child benefit (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | 146 | 176 | 149 | 85 |

| 1965 | 166 | 199 | 168 | 85 |

| 1966 | 165 | 199 | 168 | 82 |

| 1967 | 173 | 318 | 173 | 80 |

| 1968 | 173 | 318 | 173 | 77 |

| 1969 | 172 | 329 | 172 | 72 |

| 1970 | 173 | 329 | 172 | 69 |

| 1971 | 178 | 354 | 177 | 80 |

| 1972 | 187 | 356 | 183 | 75 |

| 1973 | 186 | 342 | 191 | 68 |

| 1974 | 191 | 345 | 216 | 78 |

| 1975 | 187 | 327 | 215 | 69 |

| 1976 | 189 | 323 | 219 | 72 |

| 1977 | 190 | 326 | 221 | 69 |

| 1978 | 189 | 321 | 228 | 82 |

| 1979 | 190 | 308 | 232 | 102 |

- Notes

- (a) Refers to married couple.

- (b) Refers to man plus dependent wife.

- (c) Refers to man plus wife on his insurance. After 1971 refers to recipients under 80 years old.

- (d) Includes family allowance and tax allowance combined for second child up to 1977, when these were unified into the child benefit.

Percentage change in social security benefits, prices and earnings

edit| Date | Unemployment and sickness benefit (a) | Retirement pension (b) | Prices (c) | Average earnings (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 1974 | 17.0 | 29.0 | 13.5 | 12.9 |

| April 1975 | 14.0 | 16.0 | 17.7 | 17.4 |

| November 1975 | 13.3 | 14.7 | 11.7 | 10.7 |

| November 1976 | 16.2 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 12.8 |

| November 1977 | 14.0 | 14.4 | 13.0 | 9.6 |

| November 1978 | 7.1 | 11.4 | 8.1 | 14.6 |

| Total increase October 1973 – 1978 | 114.3 | 151.6 | 109.6 | 107.9 |

- (a) Single person.

- (b) Single pensioner under age 80.

- (c) General index of retail prices.

- (d) Average gross weekly earnings of full-time adult male manual workers. For November 1978, October 1977 to October 1978 increase used.

Unemployment and sickness benefits as a percentage of income

edit| Year | Single person | Married couple | Married couple with two children | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excl. ERS | Inc. ERS (c) | Excl. ERS | Inc. ERS (c) | Excl. ERS | Inc. ERS (c) | |

| 1965 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 41.2 | 41.2 | 49.3 | 49.3 |

| 1970 | 25.0 | 53.3 | 38.4 | 65.2 | 48.3 | 72.7 |

| 1973 | 24.8 | 48.4 | 38.7 | 61.5 | 49.5 | 70.6 |

| 1974 | 25.6 | 48.6 | 39.5 | 61.6 | 50.2 | 70.3 |

| 1975 | 24.5 | 45.9 | 38.0 | 58.4 | 48.3 | 67.0 |

| 1976 | 24.9 | 46.7 | 38.3 | 59.1 | 48.4 | 67.3 |

| 1977 | 25.8 | 47.9 | 39.1 | 59.9 | 49.7 | 68.8 |

| 1978 | 25.4 | 45.1 | 38.8 | 57.4 | 49.6 | 66.9 |

- (a) After allowing for income tax and national insurance contributions.

- (b) Average earnings of adult male manual workers.

- (c) Earnings Related Supplement calculated using average earnings in October of the relevant tax year.

The real value of social security benefits, 1948–75

edit| Date | Unemployment benefit[62] | Retirement pension[62] | Supplementary benefit[62] | Child support: one child[62] | Child support: three children[62] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948, July | 19.64 | 19.64 | 17.93 | 4.87 | 17.60 |

| 1961, April | 26.88 | 26.88 | 25.31 | 4.36 | 16.62 |

| 1971, September | 34.96 | 34.96 | 33.39 | 4.27 | 15.36 |

| 1975, November | 36.47 | 42.96 | 35.10 | 3.67 | 13.81 |

See also

edit- Social welfare

- Universal basic income in the United Kingdom

- Welfare reform

- Workfare

- Workfare in the United Kingdom

Housing

References

edit- ^ Gøsta Esping-Andersen (1998). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; Polity Press. ISBN 9780745607962.

- ^ Bartholomew, J. (2004). "The Welfare State We're In" Politico's Publishing.

- ^ Scheve, Kenneth; Serlin, Theo (2022). "The German Trade Shock and the Rise of the Neo-Welfare State in Early Twentieth-Century Britain". American Political Science Review. 117 (2): 557–574. doi:10.1017/S0003055422000673. ISSN 0003-0554. S2CID 251172841.

- ^ Michael Freeden, The New Liberalism: An Ideology of Social Reform (Oxford UP, 1978).

- ^ Adams, Ian (2001). Political Ideology Today (Politics Today). Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719060205.

- ^ The Routledge encyclopaedia of philosophy (2016), p. 599 online.

- ^ a b c d "Britain 1905–1975: The Liberal reforms 1906–1914". GCSE Bitesize. BBC.

- ^ Geoffrey Lee – "The People's Budget: An Edwardian Tragedy". Archived 5 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mr Balfour's Poodle by Roy Jenkins, 2011

- ^ Gilbert, Bentley Brinkerhoff (1976). "David Lloyd George: Land, the Budget, and Social Reform". The American Historical Review. 81 (5): 1058–1066. doi:10.2307/1852870. JSTOR 1852870.

- ^ Jane Lewis, "The English Movement for Family Allowances, 1917–1945." Histoire sociale/Social History 11.22 (1978) pp. 441–59.

- ^ John Macnicol, Movement for Family Allowances, 1918–45: A Study in Social Policy Development (1980).

- ^ a b c d Steve Schifferes (26 July 2005). "Britain's long road to the welfare state". BBC News.

- ^ "Why were school dinners brought in?". National Archives.

- ^ "1908 Children's Act was created to protect the poorest children in society from abuse". Intriguing History. 12 January 2012.

- ^ Gazeley, Ian (17 July 2003). Poverty in Britain 1900–1945. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333716199.

- ^ "Case Study: Working People" (PDF). National Archives. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ David Taylor (1988). Mastering Economic and Social History. Macmillan Education. ISBN 978-0-333-36804-6.

- ^ Spicker, Paul. "Social policy in the UK". spicker.uk. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "The Beveridge Report 1942" (PDF). His Majesties publishing office. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "The Beveridge Report and the postwar reforms" (PDF). Policy Studies Institute. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ a b Crafts, N., 2023. The welfare state and inequality: were the UK reforms of the 1940s a success?, s.l.: IFS Deaton Review of Inequalities.

- ^ "A history of NHS spending in the UK". February 2017.

- ^ "A brief history of health and care funding reform in England". Socialist Health Association. 27 February 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ "NHS Charges, Third Report of Session 2005–06" (PDF). publications.parliament.uk. House of Commons Health Committee. 18 July 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Collette, C. and Laybourn, K. (2003) 'Modern Britain Since 1979. A Reader'. Chapter 2: The Welfare State, 1979–2002. I.B. Tauris.

- ^ a b Welfare spending for UK's poorest shrinks by £37bn The Guardian

- ^ a b "Welfare spending p.132" (PDF). 4 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ "Benefits for unemployed people" (PDF). A Survey of the UK Benefit System. Institute for Fiscal Studies. November 2012. p. 16.

- ^ "Benefits for people on low incomes" (PDF). A Survey of the UK Benefit System. Institute for Fiscal Studies. November 2012. p. 25.

- ^ a b Office for Budget Responsibility, 2023. A brief guide to the public finances, s.l.: Office for Budget Responsibility. https://obr.uk/docs/dlm_uploads/BriefGuide-M23.pdf

- ^ "The real significance of the winter fuel row". The Spectator. 10 September 2024. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ Bartholomew, James (2013). The Welfare State We're In (2nd ed.). Biteback Publishing. p. 480. ISBN 978-1849544504.

- ^ Steffen Mau, "The Moral Economy of Welfare States: Britain and Germany Compared." Routledge, (2004) pp.7.

- ^ Christopher Pierson and Francis Castles, "The Welfare State Reader" Polity (2006) pp.68–75

- ^ Steffen Mau, "The Moral Economy of Welfare States: Britain and Germany Compared." Routledge, (2004) pp.2.

- ^ "David Cameron: 'Don't complain about welfare cuts, go and find work'". 23 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ "Conservative conference: Welfare needs 'cultural shift'". BBC News. 8 October 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ Grice, Andrew (4 January 2013). "Voters 'brainwashed by Tory welfare myths', shows new poll". The Independent. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ "Support for benefit cuts dependent on ignorance, TUC-commissioned poll finds". TUC. Archived from the original on 7 January 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ Dixon, Hayley (13 December 2013). "Majority of benefit cheats not prosecuted, official figures show". The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Fraud and Error in the Benefit System: 2012/13 Estimates (Great Britain)" (PDF). gov.uk. Department for Work and Pensions. January 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Kinship carers at risk of poverty and debt due to welfare cuts, says charity". The Guardian. 12 October 2015.

- ^ "Church of England bishops demand action over hunger". BBC News. 20 February 2014.

- ^ Bulman, May (24 April 2018). "Food bank use in UK reaches highest rate on record as benefits fail to cover basic costs". The Independent. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ "Majority of Britons think empathy is on the wane". The Guardian. 3 October 2018.

- ^ "UK social security payments 'at lowest level since launch of welfare state'". The Guardian. 18 November 2019.

- ^ Henderson, Rick. "More benefit sanctions means more suffering for those who live on the edge". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Stone, Jon (12 November 2015). "Benefit sanctions against people with mental health problems up by 600 per cent". The Independent. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Duffy, Nick. "Government admits it has made 'no assessment' of mental health impact of benefit sanctions". i News. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Bulman, May (25 January 2020). "Ministers refuse to assess impact of benefit sanctions on mental health despite warnings of links to suicide". The Independent. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Butler, Patrick (7 February 2020). "At least 69 suicides linked to DWP's handling of benefit claims". 7 February 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Merrick, Rob (26 February 2020). "'Cover-up': DWP destroyed reports into people who killed themselves after benefits were stopped". The Independent. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Butler, Patrick (2 March 2022). "DWP blocks data for study of whether benefit sanctions linked to suicide". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ "How generous is the British welfare state?". 28 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "BMA closing statement to the UK Covid-19 Module 1". The British Medical Association is the trade union and professional body for doctors in the UK. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Barker, Margo; Russell, Jean (1 August 2020). "Feeding the food insecure in Britain: learning from the 2020 COVID-19 crisis". Food Security. 12 (4): 865–870. doi:10.1007/s12571-020-01080-5. ISSN 1876-4525. PMC 7357276. PMID 32837648.

- ^ a b c Labour and Inequality: Sixteen Fabian Essays edited by Peter Townsend and Nicholas Bosanquet

- ^ a b The Labour Party in Crisis by Paul Whiteley

- ^ Taxation, Wage Bargaining and Unemployment by Isabela Mares

- ^ a b c Labour and Equality : A Fabian Study of Labour in Power, 1974–79 edited by Nick Bosanquet and Peter Townsend

- ^ a b c d e The Welfare State in Britain since 1945 by Rodney Lowe

Bibliography

edit- Béland, Daniel, and Alex Waddan. "Conservatives, partisan dynamics and the politics of universality: reforming universal social programmes in the UK and Canada." Journal of Poverty and Social Justice 22#2 (2014): 83–97.

- Bruce, Maurice. The Coming of the Welfare State (1966) online

- Calder, Gideon, and Jeremy Gass. Changing Directions of the British Welfare State (University of Wales Press, 2012).

- Esping-Andersen, Gosta; The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, (Princeton University Press (1990).

- Ferragina, Emanuele and Seeleib-Kaiser, Martin. "Welfare Regime Debate: Past, Present, Futures?" Policy & Politics 39#4 pp. 583–611 (2011). online

- Forder, Anthony, ed. Penelope Hall's Social Services of England and Wales (Routledge, 2013).

- Fraser, Derek. The evolution of the British welfare state: a history of social policy since the Industrial Revolution (2nd ed. 1984).

- Häusermann, Silja, Georg Picot, and Dominik Geering. "Review article: Rethinking party politics and the welfare state–recent advances in the literature." British Journal of Political Science 43.01 (2013): 221–40. online

- Heclo, Hugh. Modern Social Politics in Britain and Sweden. From Relief to Income Maintenance (Yale UP, 1974) online

- Hill, Michael J. The welfare state in Britain : a political history since 1945 (1993) online

- Jones, Margaret, and Rodney Lowe, eds. From Beveridge to Blair: the first fifty years of Britain's welfare state 1948–98 (Manchester UP, 2002). online

- Laybourn Keith. The Evolution of British Social Policy and the Welfare State, c. 1800–1993 (Keele University Press. 1995). online

- Slater, Tom. "The myth of "Broken Britain": welfare reform and the production of ignorance." Antipode 46.4 (2014): 948–69. online

- Sullivan, Michael. The development of the British welfare state (1996)

- Welshman John. Underclass: A History of the Excluded, 1880–2000 (2006) excerpt

External links

edit- Text of the Beveridge Report

- The Welfare State – Never Ending Reform Brief history of the Welfare State by Frank Field (BBC website)

- The UK Economy at the Crossroads, research paper from the Center for Economic and Policy Research