The southern rockhopper penguin [3] (Eudyptes chrysocome) is a species of rockhopper penguin, that is sometimes considered distinct from the northern rockhopper penguin. It occurs in subantarctic waters of the western Pacific and Indian Oceans, as well as around the southern coasts of South America.

| Southern rockhopper penguin Temporal range: Pleistocene to recent[1]

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult in the New Island (Falkland Islands) rookery | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Sphenisciformes |

| Family: | Spheniscidae |

| Genus: | Eudyptes |

| Species: | E. chrysocome

|

| Binomial name | |

| Eudyptes chrysocome (Forster, JR, 1781)

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

See text:

| |

| |

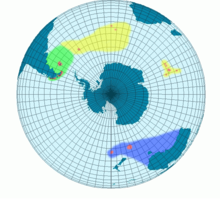

| Distribution map rockhopper penguins Green: western subspecies, blue: eastern subspecies | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

editIn 1743 the English naturalist George Edwards included an illustration and a description of the southern rockhopper penguin in the first volume of his A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Edwards based his hand-coloured etching on a preserved specimen owned by Peter Collinson.[4] When in 1758 the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus updated his Systema Naturae for the tenth edition, he placed the southern rockhopper penguin with the red-billed tropicbird in the genus Phaethon. Linnaeus included a brief description, coined the binomial name Phaethon demersus and cited Edwards' work.[5] The use of Linnaeus' binomial name was not adopted by later ornithologists, perhaps because he had already used the specific demersa for the African penguin which he placed with the wandering albatross in the genus Diomedea.[6][7]

The southern rockhopper penguin was formally described in 1781 by the German naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster under the binomial name Aptenodytes chrysocome.[8] The species is now placed in the genus Eudyptes that was introduced by the French ornithologist Louis Pierre Vieillot in 1816.[9][10] The genus name combines the Ancient Greek eu meaning "fine" with dyptes meaning "diver". The specific epithet chrysocome is from the Ancient Greek khrusokomos meaning "golden-haired" (from khrusos meaning "gold" and komē meaning "hair").[11]

Two subspecies are recognised:[10]

- E. c. filholi Hutton, FW, 1879 – Kerguelen Islands and subantarctic islands of New Zealand

- E. c. chrysocome (Forster, JR, 1781) – Cape Horn to the Falkland Islands

The rockhopper penguin complex is confusing. Many taxonomists consider all three rockhopper penguin forms subspecies. Some split the northern subspecies (moseleyi) from the southern forms (chrysocome and filholi). Still others consider all three distinct. The subspecies recognized for the southern rockhopper penguin complex are:[2]

- Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome, the western rockhopper penguin or American southern rockhopper penguin – breeds around the southern tip of South America.

- Eudyptes chrysocome filholi, the eastern rockhopper penguin or Indopacific southern rockhopper penguin – breeds on subantarctic islands of the Indian and western Pacific oceans.

The northern rockhopper penguin lives in a different water mass than the western and eastern rockhopper penguin, separated by the Subtropical Front, and they are genetically different. Therefore, northern birds are sometimes separated as E. moseleyi. The rockhopper penguins are closely related to the macaroni penguin (E. chrysolophus) and the royal penguin (E. schlegeli), which may just be a colour morph of the macaroni penguin.

Interbreeding with the macaroni penguin has been reported at Heard and Marion Islands, with three hybrids recorded there by a 1987–88 Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition.[12]

Description

editThis is the smallest yellow-crested, black-and-white penguin in the genus Eudyptes. It reaches a length of 45–58 cm (18–23 in) and typically weighs 2–3.4 kg (4.4–7.5 lb), although there are records of exceptionally large rockhoppers weighing 4.5 kg (9.9 lb).[13] It has slate-grey upper parts and has straight, bright yellow eyebrows ending in long yellowish plumes projecting sideways behind a red eye.[13]

Ecology

editThe southern rockhopper penguin group has a global population of roughly 1 million pairs. About two-thirds of the global population belongs to E. c. chrysocome which breeds on the Falkland Islands and on islands off Patagonia.[14] These include most significantly Isla de los Estados, the Ildefonso Islands, the Diego Ramírez Islands and Isla Noir. E. c. filholi breeds on the Prince Edward Islands, the Crozet Islands, the Kerguelen Islands, Heard Island, Macquarie Island, Campbell Island, the Auckland Islands and the Antipodes Islands. Outside the breeding season, the birds can be found roaming the waters offshore their colonies.[15]

These penguins feed on krill, squid, octopus, lantern fish, mollusks, plankton, cuttlefish, and mainly crustaceans.

A rockhopper penguin, named Rocky, in Bergen Aquarium in Norway lived to 29 years 4 months. It died in October 2003. This stands as the age record for rockhopper penguins, and possibly it was the oldest penguin known.[16]

Behaviour

editTheir common name refers to the fact that, unlike many other penguins which get around obstacles by sliding on their bellies or by awkward climbing using their flipper-like wings as aid, rockhoppers will try to jump over boulders and across cracks.[13]

This behaviour is by no means unique to this species however – at least the other "crested" penguins of the genus Eudyptes hop around rocks too. But the rockhopper's congeners occur on remote islands in the New Zealand region, whereas the rockhopper penguins are found in places that were visited by explorers and whalers since the Early Modern era. Hence, it is this particular species in which this behaviour was first noted.

Their breeding colonies are located from sea level to cliff-tops and sometimes inland. Their breeding season starts in September and ends in November.[13] Two eggs are laid but only one is usually incubated.[13] Incubation lasts 35 days and their chicks are brooded for 26 days.

Variation in foraging behaviour

editRockhopper penguins are known to have complex foraging behaviors. Influenced by factors such as sea ice abundance, prey availability, breeding stage, and seasonality, rockhopper penguins must be able to adapt their behavior to fit the current conditions.[17] Rockhopper penguins employ different strategies according to their conditions. When making foraging trips, rockhoppers typically leave and return to their colonies in groups. One study showed they are known for going up to 157 km (98 mi) away from their colonies when foraging.[18] Females typically forage during the day in 11–12 hour trips consisting of many dives, but they will occasionally forage at night.[17] Night dives are typically much shallower than day dives. Dives typically last around 12h, but can be up to 15hrs, with penguins leaving the colony around dawn (04:00) and returning at dusk (19:00).[19]

Rockhopper penguins employ different strategies and foraging behaviors depending on the climate and environment. A main factor is food location. Subantarctic penguins must dive for longer periods of time and much deeper in search of food than do species in warmer waters where food is more easily accessible.[17]

Benthic and pelagic dives

editRockhopper penguins are known to employ two different types of dives when foraging, pelagic and benthic dives. Pelagic dives are typically short and relatively shallow and used very frequently. Benthic dives are much deeper dives near the seafloor (up to 100 m (330 ft) deep)[19] that typically last longer and have longer bottom time. Penguins performing benthic dives typically only perform a few depth wiggles (changes in depth profile) at their maximum depth.[20] at an average speed of range of 6.9–8.1 kilometres per hour (6,900–8,100 m/h).[18] Although deeper dives tend to be a bit longer than shallow dives, foraging rockhoppers will minimize their travel time when performing benthic dives to gain maximum efficiency. Benthic dives in particular show a stronger correlation to full stomachs than pelagic dives. Emperor penguins, gentoo penguins, yellow-eyed penguins and king penguins also use this deep-dive technique to obtain food.[20]

Prey availability is dependent on many factors, such as current climate and conditions of the area. Typically, females will bring back a majority of crustaceans and occasionally some fish for their young. The female's foraging success directly affects chick growth.[17] If food is scarce, females are able to fast for very long periods of time and sometimes will only forage for the chick's benefit.[19]

Dive limitations

editBecause foraging conditions and outcomes are so variable, several factors can limit foraging practices. The timing of breeding, incubation and brooding periods greatly affect foraging time, as females are unable to leave broods for long periods of time.[18] Females during the brooding period will follow a much more fixed foraging schedule, leaving and returning to the colony at roughly the same time each day. When not in breeding season, females have much more variability in the length of foraging trips. If females have low energy levels because they are fasting while provisioning chicks, they may make several short foraging trips instead of one longer one.[17]

While benthic dives are efficient and favorable for rockhoppers, they present physiological limitations such as limits in lung capacity, which affects duration of dives. The longest aerobic dive rockhoppers can perform is about 110 seconds long,[20] but dives can last upwards of 180–190 seconds.[17][18]

Status and conservation

editThe southern rockhopper penguin group is classified as vulnerable by the IUCN.[2] Its population has declined by about one-third in the last thirty years.[15][21] This decline has earned them the classification of a vulnerable species by the IUCN. Threats to their population include commercial fishing and oil spills.[22]

With the approval of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA), Drusillas Park in East Sussex holds the studbook for rockhopper penguins in Europe. Zoo manager Sue Woodgate has specialist knowledge of the species, so the zoo is responsible for co-ordinating the movements of penguins within zoos in Europe to take part in breeding programmes and offer their advice and information about the species.[23]

Relationship with humans

editRockhopper penguins are the most familiar of the crested penguins to the general public. Their breeding colonies, namely those around South America, today attract many tourists who enjoy watching the birds' antics. Historically, the same islands were popular stopover and replenishing sites for whalers and other seafarers since at least the early 18th century. Almost all crested penguins depicted in movies, books and other media are ultimately based on Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ "Fossilworks: Eudyptes chrysocome".

- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2020). "Eudyptes chrysocome". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22735250A182762377. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22735250A182762377.en. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ English name updates – IOC Version 2.9 (July 10, 2011) Archived November 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, IOC World Bird List

- ^ Edwards, George (1751). A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Vol. Part 1. London: Printed for the author at the College of Physicians. p. 49, Plate 49.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 135.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 132.

- ^ Allen, J.A. (1904). "The case of Megalestris vs. Catharacta". The Auk. 21 (3): 345–348 [346, Footnote 1]. doi:10.2307/4070197. hdl:2027/hvd.32044107327124. JSTOR 4070197.

- ^ Forster, Johann Reinhold (1780). "Historia Aptenodytae. Generis Avium orbi Australi proprii". Commentationes Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis (in Latin). 3: 121–148 [133, 135]. Although the volume is dated 1780, the article was not published until 1781.

- ^ Vieillot, Louis Pierre (1816). Analyse d'une Nouvelle Ornithologie Élémentaire (in French). Paris: Deterville/self. pp. 67, 70. The genus name is misspelled as Endyptes on page 67.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Kagu, Sunbittern, tropicbirds, loons, penguins". IOC World Bird List Version 11.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 152, 105. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Woehler, E. J.; Gilbert, C. A. (1990). "Hybrid Rockhopper-Macaroni Penguins, interbreeding and mixed-species pairs at Heard and Marion Islands". Emu. 90 (3): 198–210. Bibcode:1990EmuAO..90..198W. doi:10.1071/MU9900198.

- ^ a b c d e Trewby, Mary (2002). Antarctica: an encyclopedia from Abbot Ice Shelf to Zooplankton. Auckland, New Zealand: Firefly Books. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-55297-590-9.

- ^ Mays, Herman L; Oehler, David A; Morrison, Kyle W; Morales, Ariadna E; Lycans, Alyssa; Perdue, Justin; Battley, Phil F; Cherel, Yves; Chilvers, B Louise; Crofts, Sarah; Demongin, Laurent; Fry, W Roger; Hiscock, Jo; Kusch, Alejandro; Marin, Manuel (December 17, 2019). Jackson, Jennifer (ed.). "Phylogeography, Population Structure, and Species Delimitation in Rockhopper Penguins ( Eudyptes chrysocome and Eudyptes moseleyi )". Journal of Heredity. 110 (7): 801–817. doi:10.1093/jhered/esz051. ISSN 0022-1503. PMC 7967833. PMID 31737899.

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2008). [2008 IUCN Redlist status changes]. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ^ Glenday, Craig (ed.) (2008). Guinness World Records 2008. Guinness Media, Inc. ISBN 1-904994-19-9

- ^ a b c d e f Tremblay, Yann; Cherel, Yves (2003). "Geographic variation in the foraging behaviour, diet and chick growth of rockhopper penguins". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 251: 279–297. Bibcode:2003MEPS..251..279T. doi:10.3354/meps251279.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Christopher (1987). "Traveling Speed and Foraging Range of Macaroni and Rockhopper Penguins at Marion Island (Velocidad de Movimiento y Extensión de las Áreas de Forrajeo de los Pingüinos Eudyptes chrysolophus y e. Chrysocome)". Journal of Field Ornithology. 58 (2): 118–125. JSTOR 4513209.

- ^ a b c Putz, Klemens (November 29, 2005). "Diving characteristics of southern rockhopper penguins (Eudyptes c. chrysocome) in the southwest Atlantic". Marine Biology. 149 (2): 125–137. doi:10.1007/s00227-005-0179-y. S2CID 84393587.

- ^ a b c Tremblay, Yann; Cherel, Yves (2000). "Benthic and pelagic dives: a new foraging behaviour in rockhopper penguins". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 204: 257–267. Bibcode:2000MEPS..204..257T. doi:10.3354/meps204257.

- ^ BirdLife International (2008) Southern Rockhopper Penguin Species Factsheet Archived December 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ^ Devon Phelan. "Eudyptes chrysocome rockhopper penguin". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ "Wild penguins get a helping hand from Drusillas Park in Sussex". Drusillas Park (Press release). 2012.