The Whiggamore Raid (or "March of the Whiggamores") was a march on Edinburgh by supporters of the Kirk faction of the Covenanters to take power from the Engagers whose army had recently been defeated by the English New Model Army at the Battle of Preston (1648).[1]

| Whiggamore Raid | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Scottish Civil War | |||||||

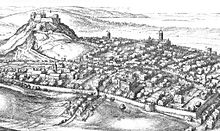

Engraving of Edinburgh by Wenceslaus Hollar, 1670 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Whiggamores (later shortened to Whigs)—a term most likely originating from the Scots for "mare drivers"[2]—became a nickname for the Kirk party who were against the Engagement with King Charles I.[1]

Prelude

editAfter defeating the Duke of Hamilton at the Battle of Preston (17–19 August 1648), Oliver Cromwell had still to deal with the forces under Sir George Monro and Sir Philip Musgrave, making in all about 7,000 men. Monro, however, not being on good terms with his English allies, made his way through Durham to the Anglo-Scottish border, and, crossing the Tweed into Scotland on 8 September 1648, left Musgrave (who had retreated into Appleby and capitulated on 9 October 1648) to his fate. The Earl of Lanark and the Committee of Estates, anxious to hold Cromwell back from carrying the pursuit across the Border, gave orders that no Englishman who had been in arms in conjunction with Hamilton or Monro should be admitted into Scotland.[3] By this time Cromwell was at Durham pushing steadily northwards. He soon learnt that he would not be without potent allies in Scotland itself.

Raid

editArchibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll had seen in Hamilton's defeat at Preston an opportunity for recovering the power that he had lost. Presbyterian ministers preached in his favour from one end of the country to the other. Robert, Lord Eglinton roused the stern Presbyterians of the west, who were known in Edinburgh as Whiggamores (reportedly, from the cry of "Whiggam" with which they encouraged their horses). The crowd of half-armed peasants who followed in Alexander, Earl of Eglinton's train, and to whose incursion the name of the Whiggamore Raid was given, had the popular feeling behind them. They easily took possession of Edinburgh, where old Leven secured the castle for them. David Leslie, who had refused to fight for Hamilton, placed his sword at the disposal of Argyll, and the Chancellor Loudoun, who had been long hesitating between the two parties, now openly deserted the Committee of Estates and being himself a Campbell brought what authority he possessed to the support of the head of his family (the Marquess of Argyll).[4][5][6]

Aftermath

editThe Committee of Estates, thrust out of Edinburgh, took refuge under Monro's protection at Stirling, where they found themselves again opposed by the Whiggamores,[7] and by the followers of the few Lowland noblemen who adopted their cause. There was a skirmish at Stirling on 12 September 1648. Lanark and the officers of Monro's army argued strongly in favour of fighting the insurgents, believing that it would be easy to gain a victory over their heterogeneous force. The members of the Committee of Estates were, however, too conscious of their political isolation to approve of such a course, so, with both sides worried that the English Parliamentary forces were going to take advantage of Scottish disunity and invade Scotland, they promptly opened negotiations. On 26 September the Committee of Estates abandoned all claim to the government of the country. It was agreed that Sir George Monro's soldiers should return to Ireland, and that all persons who had taken part in the defence of the Engagement should resign whatever offices and places of trust they held in Scotland.[8][9]

See also

edit- British Whig Party

- Liberal Party (UK)

- Patriot Whigs or Patriot Party

- Radical Whigs

Notes

edit- ^ a b Herman 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Hoad 1996, Whig.

- ^ Gardiner 1905, p. 227 cites Musgrave's relation, Clarendon MSS. 2,867; Burnet, vi. 78, 79.

- ^ Gardiner 1905, p. 228.

- ^ Gardiner 1905, p. 228 cite notes Loudoun's explanation of his change of front, (Gardiner 1905, p. 95, note 2). An explanation discreditable to Loudoun is given in Burnet's Hist, of his Own Time, ed. 1823, i. 75.

- ^ For Robert Lord Eglinton and Alexander 6th Earl of Eglinton's involvement see Furgol 2009

- ^ Gardiner 1905, p. 228 cites Burnet's Lives of the Hamiltons, vi. 81-83.

- ^ Gardiner 1905, p. 228 cites Burnet's Lives of the Hamiltons, vi. 81-94; Bloody News from Scotland, E. 465, 22.

- ^ Manganiello 2004, pp. 540, 576.

References

edit- Furgol, Edward M. (October 2009) [2004]. "Montgomery [Montgomerie; formerly Seton], Alexander". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19053. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Herman, Arthur (2001), How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe's Poorest Nation Created Our World & Everything in It, New York: Crown Pub, p. 46, ISBN 0-609-60635-2

- Hoad, F. T., ed. (1996), "Whig", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, ISBN 9780192830982

- Manganiello, Stephen C. (2004), The concise encyclopedia of the revolutions and wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639–1660, Scarecrow Press, pp. 540, 576, ISBN 0-8108-5100-8

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Gardiner, Samuel Rawson (1905), History of the great civil war, 1642-1649, vol. IV (New impression ed.), London, New York, and Bombay: Longmans, Green and Company, pp. 227–228

Further reading

edit- Campbell, Alastair; Campbell, Alastair, Campbell of Airds (2000), A History of Clan Campbell: From Flodden to the Restoration, A History of Clan Campbell, Alastair Campbell Campbell of Airds, vol. 2 (illustrated ed.), Edinburgh University Press, pp. 251–252, ISBN 9781902930183

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)