Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen[b] KCMG (13 January 1911 – 23 April 2005) was an Australian politician. He was the longest-serving premier of Queensland, holding office from 1968 to 1987 as state leader of the National Party (earlier known as the Country Party).

The Honourable Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

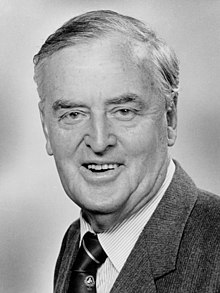

Official portrait, c. 1980 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31st Premier of Queensland Elections: 1969, 1972, 1974, 1977, 1980, 1983, 1986 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 8 August 1968 – 1 December 1987 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Elizabeth II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | Alan Mansfield Colin Hannah James Ramsay Walter Campbell | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Gordon Chalk William Knox Llew Edwards Bill Gunn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Gordon Chalk | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Mike Ahern | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20th Deputy Premier of Queensland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 August 1968 – 8 August 1968 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Gordon Chalk | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Gordon Chalk | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Gordon Chalk | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Johannes Bjelke-Petersen 13 January 1911 Dannevirke, New Zealand | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 23 April 2005 (aged 94) Kingaroy, Queensland, Australia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Kingaroy, Queensland, Australia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Citizenship | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Australian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Bjelke-Petersen family | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | Taabinga State School | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bjelke-Petersen was born in New Zealand's North Island to Danish immigrant parents. His family moved back to Australia when he was a child and settled on farming property near Kingaroy, Queensland. He left school at the age of 14 and went into farming. Bjelke-Petersen was elected to the Kingaroy Shire Council in 1946 and to the Queensland Legislative Assembly at the 1947 state election. He would serve in state parliament for over 40 years, holding the seats of Nanango (1947–1950) and Barambah (1950–1987).

Bjelke-Petersen was appointed as a government minister in 1963 and succeeded as premier and Country Party leader in 1968 following the death of Jack Pizzey. He would lead the party to seven consecutive election victories, governing in coalition with the Liberal Party until 1983. His first three electoral victories saw his party benefit from a system of rural malapportionment later nicknamed the "Bjelkemander", which allowed him to remain premier despite frequently receiving a smaller number of votes than the state's two other major parties.[2][3] The system earned Bjelke-Petersen the nickname "the Hillbilly Dictator". Regardless, he was a highly popular figure among conservative voters and over the course of his 19 years as premier he tripled the number of Country/National voters and doubled the party's percentage vote. After the Liberal Party pulled out of the Coalition government in 1983, Bjelke-Petersen reduced his former partners to a mere eight seats in an election held later that year. In 1985 Bjelke-Petersen launched a campaign to move into federal politics to become prime minister, though the campaign was eventually aborted.

Bjelke-Petersen earned himself a reputation as a "law and order" politician with his repeated use of police force against street demonstrators[3] and strongarm tactics with trade unions, leading to descriptions of Queensland under his leadership as a police state. Starting in 1987, this administration came under the scrutiny of a royal commission into police corruption and its links with state government ministers. Bjelke-Petersen was unable to recover from the series of damaging findings and after initially resisting a party vote that replaced him as leader, retired from politics on 1 December 1987. Two of his state ministers, as well as the police commissioner Bjelke-Petersen had appointed and later knighted, were jailed for corruption offences and in 1991 Bjelke-Petersen, too, was tried for perjury over his evidence to the royal commission; the jury failed to reach a verdict as the jury foreman was a member of the Young Nationals and a member of the "Friends of Joh" group, and Bjelke-Petersen was deemed too old to face a second trial.

During the Bjelke-Petersen era the state underwent considerable economic development.[4] He was one of the most well-known and controversial figures of 20th-century Australian politics because of his uncompromising conservatism (including his role in the downfall of the Whitlam federal government), political longevity, and the institutional corruption of his government.

Early life

editBjelke-Petersen was born on 13 January 1911 in Dannevirke, a town in the North Island of New Zealand. He was the second of three children born to Maren (née Poulsen) and Carl George Bjelke-Petersen.[5] His parents were both Danish emigrants to Australia; his mother had arrived in Queensland as a child while his father moved to Australia as a young man. His father's siblings included prominent novelist Marie Bjelke-Petersen and physical culture advocate Christian Bjelke-Petersen.[6]

Bjelke-Petersen's parents had moved from Queensland to New Zealand in 1903, where his father, a Lutheran minister, was posted to the originally Scandinavian settlement of Dannevirke.[5] The family returned to Australia in 1913 to aid his father's health, settling on a farming property named "Bethany" near Kingaroy, Queensland.[7] Bjelke-Petersen was raised in a conservative religious household, with the Sabbath strictly observed and daily Bible readings; his mother ran a Sunday school from the family home.[8] At their father's insistence, he and his siblings were raised speaking Danish as their home language, something atypical of Scandinavian immigrants in Australia who more often rapidly adopted English.[9]

The young Bjelke-Petersen suffered from polio, leaving him with a lifelong limp. The family was poor, and his father was frequently in poor health. Bjelke-Petersen left formal schooling at age 14 to work with his mother on the farm, though he later enrolled in correspondence school and undertook a University of Queensland extension course on the "Art of Writing". He taught Sunday school, delivered sermons regularly in nearby towns and joined the Kingaroy debating society.[10]

In 1933, Bjelke-Petersen began work land-clearing and peanut farming on the family's newly acquired second property. His efforts eventually allowed him to begin work as a contract land-clearer and to acquire further capital which he invested in farm equipment and natural resource exploration. He developed a technique for quickly clearing scrub by connecting a heavy anchor chain between two bulldozers. By the time he was 30, he was a prosperous farmer and businessman.[10] Obtaining a pilot's licence early in his adult life, Bjelke-Petersen also started aerial spraying and grass seeding to further speed up pasture development in Queensland.[11]

After failing in a 1944 plebiscite against the sitting member to gain Country Party endorsement in the state seat of Nanango,[12] based on Kingaroy, Bjelke-Petersen was elected in 1946 to the Kingaroy Shire Council, where he developed a profile in the Country Party.[13] With the support of local federal member and shire council chairman Sir Charles Adermann and state opposition leader Sir Frank Nicklin, he gained Country Party endorsement for Nanango and was elected a year later at age 36, going on to give regular radio talks and becoming secretary of the local Nationals branch.[13] He would hold this seat, renamed Barambah in 1950, for the next 40 years. The Labor Party had held power in Queensland since 1932 and Bjelke-Petersen spent eleven years as an opposition member.

Rise to power, 1952–1970

editOn 31 May 1952, Bjelke-Petersen married typist Florence Gilmour, who would later become a significant political figure in her own right.

In 1957, following a split in the Labor Party, the Country Party under Nicklin came to power, with the Liberal Party as a junior coalition partner. This was a reversal of the situation at the national level. Queensland is Australia's least centralised mainland state; the provincial cities between them have more people than the Brisbane area. In these areas, the Country Party was stronger than the Liberal Party. As a result, the Country Party had historically been the larger of the two non-Labor parties, and had been senior partner in the Coalition (until the parties merged) since 1925.

In 1963 Nicklin appointed Bjelke-Petersen as minister for works and housing,[14] a portfolio that gave him the opportunity to bestow favours and earn the loyalty of backbenchers by approving construction of schools, police stations and public housing in their electorates.[15] At various times, he also served as acting minister for education, police, Aboriginal and Island Affairs, local government and conservation and labour and industry.[15] He would serve in cabinet without interruption until his retirement in 1987. Only Thomas Playford IV, who served in the South Australian cabinet without interruption from 1938 to 1965, served longer as a federal or state cabinet minister.

Nicklin retired in January 1968 and was succeeded as Premier and Country Party leader by Jack Pizzey; Bjelke-Petersen was elected unopposed as deputy Country Party leader. On 31 July 1968, after just seven months in office, Pizzey suffered a heart attack and died. Deputy Premier and Liberal leader Gordon Chalk was sworn in as caretaker premier until the Country Party could elect a new leader, with Bjelke-Petersen as deputy premier. The Country Party had 27 seats in Parliament; the Liberals had 20. Nonetheless, there was some dispute over whether the Liberals should take senior status, which would have made Chalk premier in his own right. Matters were brought to a head when Bjelke-Petersen—elected Country Party leader within days of Pizzey's death—threatened to pull the Country Party out of the Coalition unless he became Premier. After seven days Chalk accepted the inevitable, and Bjelke-Petersen was sworn in as Premier on 8 August 1968. He remained Police Minister.[15][16]

Conflict of interest, party revolt

editWithin months of becoming premier, Bjelke-Petersen encountered his first controversy over allegations of conflict of interest. In April 1959, while still a backbencher, he had paid £2 for an Authority to Prospect, giving him the right to search for oil over 150,000 square kilometres (58,000 sq mi) near Hughenden in far north Queensland. The next month he incorporated a company, Artesian Basin Oil Co. Pty Ltd, of which he was sole director and shareholder, and the same day entered an agreement to sell 51% of the company's shares to an American company for £12,650. The following day he sought the consent of Mines Minister Ernie Evans to transfer the oil search authority to Artesian for £2; the consent was given a week later.

When the Taxation Commissioner ruled that the £12,650 windfall from the £2 authority was a taxable profit, Bjelke-Petersen appealed, eventually taking the matter to the High Court. The appeal was dismissed, with Justice Taylor ruling that Bjelke-Petersen's six million percent gain from the £2 authority arose from "a profit-making undertaking". In 1962 Artesian transferred its Authority to Prospect to a new company, Exoil NL, for £190,000, and Bjelke-Petersen in turn bought a million shares in Exoil.

On 1 September 1968, three weeks after becoming premier, Bjelke-Petersen's government gave two companies, Exoil NL and Transoil NL—in both of which he was a major shareholder—six-year leases to prospect for oil on the Great Barrier Reef north of Cooktown. Opposition Leader Jack Houston revealed the Premier's financial involvement in the companies at a press conference in March 1969, where he asserted Bjelke-Petersen had gained "fabulous wealth" from the £2 prospecting authority, which had now mushroomed into Exoil shares worth AU$720,000. Bjelke-Petersen said he had done nothing wrong, but resigned his directorship of Artesian in favour of his wife.[16]

The Country-Liberal coalition was returned to power at the 1969 Queensland election, with the state's system of electoral malapportionment delivering the Country Party 26 seats—a third of the parliament's 78 seats—from 21.1% of the primary vote, the Liberals taking 19 seats from 23.7% of the vote and the Labor Party's 45.1% share of the vote leaving it with 31 seats.

Further controversy followed. In June 1970 it was revealed that a number of Queensland government ministers and senior public servants, as well as Florence Bjelke-Petersen, had bought shares in the public float of Comalco, a mining company that had direct dealings with the government and senior ministers. The shares finished their first day of trading at double the price the ministers had paid. Bjelke-Petersen again rejected claims of a conflict of interest, but the Country Party state branch changed its policy to forbid the acceptance of preferential share offers by ministers or members of parliament.[17][18]

In October, the Country Party lost a by-election in the Gold Coast seat of Albert, prompting several nervous MPs to make plans to oust Bjelke-Petersen and replace him with deputy leader Ron Camm. Bjelke-Petersen spent the night and the next morning calling MPs to bolster support, surviving a party room vote by a margin of one, after producing a proxy vote of an MP who was overseas and uncontactable. Plans by dissident Country Party members to support a Labor vote of no confidence on the floor of the legislature were quashed after the intervention of party president Robert Sparkes, who warned that anyone who voted against Bjelke-Petersen would lose Country Party preselection at the next state election.[17][18]

1971 state of emergency

editBjelke-Petersen seized on the controversial visit of the Springboks, the South African rugby union team, in 1971 to consolidate his position as leader with a display of force.[19]

Springboks matches in southern states had already been disrupted by anti-apartheid demonstrations and a match in Brisbane was scheduled for 24 July 1971, the date of two Queensland by-elections. On 14 July Bjelke-Petersen declared a month-long state of emergency covering the entire state, giving the government almost unlimited power to quell what the government said was expected to be "a climax of violent demonstrations".[19][20][21] Six hundred police were transported to Brisbane from elsewhere in the state.[22]

In the week before the match, 40 trade unions staged a 24-hour strike, protesting against the proclamation. A crowd of demonstrators also mounted a peaceful protest outside the Springboks' Wickham Terrace motel and were chased on foot by police moments after being ordered to retreat, with many police attacking the crowd with batons, boots and fists.[20] It was one of a series of violent attacks by police on demonstrators during the Springboks' visit to Queensland.[23] The football game was played to a crowd of 7000 behind a high barbed-wire fence without incident.[19] The state of emergency, which gave the government the appearance of being strong-willed and decisive,[19] helped steer the government to victory in both by-elections held on match day. Police Special Branch member Don Lane was one of those elected, becoming a political ally of the Premier.[24]

Bjelke-Petersen praised police for their "restraint" during the demonstrations and rewarded the police union for its support with an extra week's leave for every officer in the state.[22] He described the tension over the Springboks' tour as "great fun, a game of chess in the political arena". The crisis, he said, "put me on the map".[25]

The following May—six months before the Labor Party's landslide victory at the 1972 Australian federal election under Gough Whitlam—the Country-Liberal coalition gained another comprehensive win at the 1972 Queensland state election: Bjelke-Petersen's party took 26 seats with 20% of the vote, the Liberals took 21 seats with a 22.2% share and Labor got 33 seats from 46.7%. It was the first state election to be fought following a 1971 electoral redistribution that added four seats to the parliament and created four electoral zones with a weightage towards rural seats, with the result that while Brisbane electorates averaged about 22,000 voters, some rural seats such as Gregory and Balonne had fewer than 7000.[2]

Political ascendancy, 1971–78

editFrom 1971, under the guidance of newly hired press secretary Allen Callaghan, a former Australian Broadcasting Corporation political journalist, Bjelke-Petersen developed a high level of sophistication in dealing with news media. He held daily media conferences where he joked that he "fed the chooks", established direct telex links to newsrooms where he could feed professionally written media releases and became adept at distributing press releases on deadline so journalists had very little chance to research news items.[26] The Premier's public profile rose rapidly with the resulting media coverage.[27] Bjelke-Petersen began regular media and parliamentary attacks on the Whitlam Labor government, vowing to have it defeated, and he and Whitlam exchanged frequent verbal barbs, culminating in the prime minister's 1975 description of the Queensland premier as "a Bible-bashing bastard ... a paranoic, a bigot and fanatical".[28] The pair clashed over federal plans to halt the sale of Queensland coal to Japan, take over the administration of Aboriginal affairs, remove outback petrol subsidies and move the Australian border in the Torres Strait southwards to a point midway between Queensland and Papua New Guinea. Bjelke-Petersen also vehemently opposed the Whitlam government's proposal for Medicare, a publicly funded universal health care system. The battles helped to consolidate Bjelke-Petersen's power as he used the media to emphasise a distinctive Queensland identity he alleged was under threat from the "socialist" federal government.[29]

The Queensland government bought a single-engine aircraft for the Premier's use in November 1971, upgrading it to a twin-engine aircraft in 1973 and even bigger model in 1975. Bjelke-Petersen, a licensed pilot, used it often to visit far-flung parts of the state to campaign and boost his public profile.[30]

In April 1974, in a bid to broaden its appeal beyond rural voters, the Country Party changed its name to the National Party.[31]

The Gair affair

editIn April 1974 Bjelke-Petersen outmanoeuvred Whitlam after the prime minister offered Democratic Labor Party senator Vince Gair, a bitter opponent of the government, the position of ambassador to Ireland as a way of creating an extra vacant Senate position in Queensland. Whitlam, who lacked a majority in the Senate, hoped Gair's seat would be won by his Labor Party. But when the arrangement was disclosed by newspapers before Gair had resigned from the Senate, the Opposition conspired to keep Gair away from the Senate President (to whom Gair had not yet given his resignation) and ensured he voted in a Senate debate late that night to avoid any move to backdate the resignation.[32] At 5.15pm the Queensland Cabinet met to pass a "flying minute" and advised the Governor, Sir Colin Hannah, to issue writs for five, rather than six, vacancies, denying Labor the chance of gaining Gair's Senate spot.[33] The intention was to have Gair's seat declared a casual vacancy, allowing Bjelke-Petersen to fill the vacancy until the next election.

Labor argued that Gair's appointment, and hence his departure from the senate, was effective from no later than when the Irish government accepted his appointment, in March. This was a matter of protracted debate in the Senate over many days, and was never resolved, but it was rendered irrelevant when Whitlam called a double dissolution of both Houses, in an election gamble he only narrowly won.

1974 state election

editIn October 1974 Bjelke-Petersen called an early election, setting the 1974 Queensland election for 7 December, declaring it would be fought on "the alien and stagnating, centralist, socialist, communist-inspired policies of the federal Labor government".[34] The premier visited 70 towns and cities in the five-week campaign and attracted record crowds to public meetings. The result was a spectacular rout for the Labor Party, which was left with just 11 of the legislature's 82 seats after a 16.5 percent swing to the Coalition, leading observers to call Labor's caucus a "cricket team." The only seat Labor retained north of Rockhampton was Cairns, by fewer than 200 votes. The National Party, contesting its first state election under the new name and fielding candidates in just 48 seats, lifted its vote from 19.7 percent to 28 percent, creating a threat for the Liberal Party, and also picked up a number of city seats including its first in Brisbane, the eastern suburbs seat of Wynnum. The Nationals even managed to oust Labor leader Perc Tucker in his own seat. The Australian newspaper named Bjelke-Petersen, whom it described as the "undistinguished" Queensland premier, "Australian of the Year", citing "the singular impact he has exerted on national political life".[34][35]

Role in the Whitlam dismissal

editIn 1975, Bjelke-Petersen played what turned out to be a key role in the political crisis that brought down the Whitlam government. When Queensland Labor Senator Bertie Milliner died suddenly in June 1975, Bjelke-Petersen requested from the Labor Party a short list of three nominees, from which he would pick one to replace Milliner.[33] The ALP refused to supply such a list, instead nominating Mal Colston, an unsuccessful Labor candidate in the 1970 election, whom Bjelke-Petersen duly rejected. On 3 September Bjelke-Petersen selected political novice Albert Field, a long-time ALP member who was critical of the Whitlam government.[33] Field's appointment was the subject of a High Court challenge and he was on leave from October 1975. During this period, the Coalition led by Malcolm Fraser declined to allot a pair to balance Field's absence. This gave the Coalition control over the Senate. Fraser used that control to obstruct passage of the Supply Bills through Parliament, denying Whitlam's by now unpopular government the legal capacity to appropriate funds for government business and leading to his dismissal as Prime Minister.[33] During the tumultuous election campaign precipitated by Whitlam's dismissal by the governor-general John Kerr, Bjelke-Petersen alleged that Queensland police investigations had uncovered damaging documentation in relation to the Loans Affair. This documentation was never made public and these allegations remained unsubstantiated.[33]

Taxation reform

editQueensland was renowned for being the lowest taxed state in Australia for much of Bjelke-Petersen's tenure. Over heated objections by Treasurer Gordon Chalk,[36] Bjelke-Petersen in 1977 announced the removal of state death duties, a move that cost his state $30 million in revenue. So many New South Wales and Victorian residents sought to establish their permanent address in Queensland as a result, boosting state coffers with stamp duty from property transactions, that other states followed suit within months and also abolished the tax.[37] To help compensate for lost revenue, the government introduced football pools; four years later the government granted a casino licence on the Gold Coast, although this too was mired in allegations of corruption and favouritism.[38]

Restriction of civil liberties, growth of police power

editIssues of police powers and civil liberties, first raised at the time of the 1971 Springboks tour, resurfaced in July 1976 with a major street demonstration in which more than a thousand university students marched towards the Brisbane city centre to demand better allowances from the federal government. Police stopped the march in Coronation Drive and television cameras captured an incident during the confrontation in which a police inspector struck a 20-year-old female protester over the head with his baton, injuring her. When Police Commissioner Ray Whitrod announced he would hold an inquiry, a move supported by Police Minister Max Hodges, Bjelke-Petersen declared there would be no inquiry. He told reporters he was tired of radical groups believing they could take over the streets. Police officers passed a motion at a meeting commending the premier for his "distinct stand against groups acting outside the law" and censured Whitrod. A week later Bjelke-Petersen relieved Hodges of his police portfolio.[39][40] Secure in the knowledge that they had the Premier's backing, police officers continued to act provocatively, most notably in a military-style raid on a hippie commune at Cedar Bay in Far North Queensland late the following month.[41] The police, who had been looking for marijuana, set fire to the residents' houses and destroyed their property.

Bjelke-Petersen rejected calls for an inquiry into the raid, declaring the government would believe the police and claiming the public clamour was "all part of an orchestrated campaign to legalise marijuana and denigrate the police". In defiance of the premier, Whitrod went ahead with an inquiry anyway and on 16 November ordered summonses be issued against four police officers on more than 25 charges, including arson. He chose the same day to announce that he was quitting his post. Whitrod claimed his resignation marked a victory for the forces of corruption, but said he had decided to quit rather than tolerate further political interference by the premier and new Police Minister Tom Newbery. Whitrod said Queensland showed signs of becoming a police state and he compared the growing political interference in law enforcement to the rise of the German Nazi state.[39] Whitrod was replaced by Assistant Commissioner Terry Lewis, despite Whitrod's warning to the Police Minister that he was corrupt.[24]

In 1977, Bjelke-Petersen announced that "the day of street marches is over", warning protesters, "Don't bother applying for a march permit. You won't get one. That's government policy now!"[42] Liberal parliamentarians crossed the floor defending the right of association and assembly.[43] One Liberal MP, Colin Lamont, told a meeting at the University of Queensland that the premier was engineering confrontation for electoral purposes and was confronted two hours later by an angry Bjelke-Petersen who said he was aware of the comments. Lamont later said he learned the Special Branch had been keeping files on Liberal rebels and reporting, not to their Commissioner, but directly to the Premier, commenting: "The police state had arrived."[43] When, after two ugly street battles between police and right-to-march protesters, the Uniting Church Synod called on the government to change the march law, Bjelke-Petersen accused the clergy of "supporting communists". His attack sparked a joint political statement by four other major religious denominations, which was shrugged off by the premier.[37]

The government's increasingly hardline approach to civil liberties prompted Queensland National Party president Robert Sparkes to warn the party that it was developing a dangerous "propaganda-created" ultra-conservative, almost fascist image. He told a party conference: "We must studiously avoid any statements or actions which suggest an extreme right-wing posture."[37] Bjelke-Petersen ignored the advice. He condemned the use of Australian foreign aid to prop up communist regimes, urged Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser to stop criticising the governments of South Africa and Rhodesia and from 1977 proposed Queensland secede from Australia and establish its own currency.[37] He also accused political opponents of being covert communists bent on chaos, observing: "I have always found ... you can campaign on anything you like but nothing is more effective than communism ... If he's a Labor man, he's a socialist and a very dangerous man."[44]

Three weeks before the 1977 Queensland election, 400 demonstrators were arrested in what a Melbourne newspaper called "Joh's War". Aided by an electoral redistribution that removed two Liberal-held seats, the Nationals won 35 out of 82 seats, compared with 24 for the Liberals and 23 for a resurgent Labor Party. It was the first time in Queensland political history the Nationals had outpolled the Liberals. Bjelke-Petersen used the party's strength to move key Cabinet posts that had long held by the Liberals into the hands of National Party ministers.[37] In October 1978 thousands of demonstrators again attempted to defy anti-march laws with a protest march in Albert St, Brisbane, which was again repulsed by police lined five deep.[45] In a Brisbane byelection a month later National Party support slumped to just 10 percent, half of what party strategists had expected. But by the end of 1978, both the state Liberal and Labor parties had new parliamentary leaders—the fourth Labor opposition leader during Bjelke-Petersen's reign and the third Liberal leader.[45]

Disintegration of National–Liberal coalition, 1980–86

editFlorence Bjelke-Petersen was elected to the Senate in October 1980 as a National Party member and six weeks later Joh was successful for a fifth time as premier at the 1980 Queensland election, with the Nationals converting a 27.9 percent primary vote—their highest ever—into 35 of the parliament's 82 seats, or 43 percent of seats. It also created a record 13-seat lead over their coalition partners, the Liberals, who had campaigned by offering Queenslanders an alternative style of moderate government.[46]

The Nationals picked up all four Gold Coast seats and all those on the Sunshine Coast. Once again the premier took advantage of his party's dominance over the Liberals in Cabinet, this time demanding that the seven Liberal ministers sign a coalition agreement in which they promised unquestioned allegiance to Cabinet decisions. The move turned the Nationals' 35 votes to a guaranteed majority of 42 in the House, effectively neutralising any potential opposition by the 15 Liberal backbenchers.[38]

Bjelke-Petersen began making appointments, including judges and the chairmanship of the Totalisator Agency Board, that had traditionally been the domain of Liberal ministers, and accusations arose of political interference and conflicts of interest as mining contracts, casino licences and the rights to build shopping complexes were awarded to business figures with National Party links.[38] Accusations of political interference also arose when police released without charge TAB chairman Sir Edward Lyons, a National Party trustee and close friend of Bjelke-Petersen, after a breathalyser test showed he was driving with more than double the legal blood alcohol limit.[38][47]

Relations with the Liberal Party continued to deteriorate. By August 1983, after 26 years of coalition, they had reached their nadir.[48] Bjelke-Petersen was angered by a Liberal Party bid to establish a public accounts committee to examine government expenditure. Shortly afterward, Liberal leader Llew Edwards was ousted in a party room coup by Terry White, who had long advocated a greater role for the Liberals in the Coalition. Bjelke-Petersen refused to give Edwards' old post of deputy premier to White, choosing instead to adjourn parliament—which had sat for just 15 days that year—declined to say when it would sit again, and insisted he could govern alone without the need of a coalition, commenting: "The government of Queensland is in very, very good hands."[48] Labor leader Tom Burns said the closure of parliament showed "that no rules exist in the state of Queensland." In a fortnight of political crisis, Bjelke-Petersen defied an ultimatum by Liberal parliamentarians to accept their leader in Cabinet, prompting White to tear up the Coalition agreement and lead the Liberals to the crossbench.[49]

Watching with satisfaction as the Liberal Party engaged in vitriolic infighting, Bjelke-Petersen called an election for 22 October, claiming: "I really believe we can govern Queensland in our own right."[48] The campaign coincided with the launch of an "official" Bjelke-Petersen biography, Jigsaw, which lauded him as a "statesman extraordinaire" and "protectorate of Queensland and her people".[48] Further rubbing salt in the wounds of his former coalition partners, his campaign was boosted by the support of prominent Liberals from other states including Tasmanian premier Robin Gray and former Victorian and NSW premiers Sir Henry Bolte and Tom Lewis. The Nationals also poured significant resources into Brisbane-area Liberal seats, seeing a chance to not only win government in their own right, but destroy their former Liberal partners.

Three months before his 73rd birthday, Bjelke-Petersen and his party recorded a resounding victory, attracting 38.9 percent of the primary vote to give them exactly half the parliament's 82 seats, just one short of a majority. The Keith Wright-led Labor Party, with 44 percent of the vote, won 32 seats. The Liberals were decimated, losing all but eight of their 21 seats. Bjelke-Petersen openly urged Liberals to cross the floor to the Nationals in hopes of getting an outright majority. Just three days later, two Liberals—former ministers Don Lane and Brian Austin—took up Bjelke-Petersen's offer and joined the Nationals in return for seats in cabinet. With Lane and Austin's defections, the National Party was able to form a majority government for the first time at the state level in Australia.

In 1984 Bjelke-Petersen was created a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) for "services to parliamentary democracy".[50] Author Evan Whitton suggests the premier had made the nomination himself.[51]

In 1986 Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke discontinued knighthoods in Australia and it was largely in response to Bjelke-Petersen's knighthood. When Liberal Prime Minister Tony Abbott brought back knighthoods in 2014 he insisted that politicians would not be eligible citing Sir Joh as a reason for the ineligibility. [52]

In 1985 Bjelke-Petersen unveiled plans for another electoral redistribution to create seven new seats in four zones: four in the state's populous south-east (with an average enrolment of 19,357 electors per seat) and three in country areas (with enrolments as low as 9386). The boundaries were to be drawn by electoral commissioners specially appointed by the government; one of them, Cairns lawyer Sir Thomas Covacevich, was a fundraiser for the National Party.[53] The malapportionment meant that a vote in the state's west was worth two in Brisbane and the provincial cities. A University of Queensland associate professor of government described the redistribution as "the most criminal act ever perpetrated in politics ... the worst zonal gerrymander in the history of the world" and the most serious action of Bjelke-Petersen's political career.[54]

A "Joh for PM" campaign was conceived in late 1985, driven largely by a group of Gold Coast property developers,[55] promoting Bjelke-Petersen as the most effective conservative challenger to Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke, and at the 1986 Queensland election he recorded his biggest electoral win ever, winning 49 of the state's 89 seats with 39.6 percent of the primary vote. The ALP's 41.3 percent share of the vote earned it 30 seats, while the Liberal Party won the remaining 10 seats. In his victory speech, Bjelke-Petersen declared the Nationals had prevailed over the "three forces" who had opposed it: "We had the ALP organisation with its deceits, deception and lies, we had the media encouraging and supporting them, and we had the Liberal Party ... our assault on Canberra begins right now."[56]

It was the seventh and final electoral victory of the Bjelke-Petersen era. In January 1987 the premier handed control of the state to Deputy Premier Bill Gunn and announced he would seek election to the House of Representatives, formally embarking on his "Joh for Canberra" push. By early 1987 the campaign, with its promise of a 25 percent flat tax, was attracting the support of 20 per cent of voters in opinion polls.[57]

Downfall and resignation: 1987

editIn late 1986, two journalists, the ABC's Chris Masters and The Courier-Mail's Phil Dickie, independently began investigating the extent of police and political corruption in Queensland and its links to the National Party state government. Dickie's reports, alleging the apparent immunity from prosecution enjoyed by a group of illegal brothel operators, began appearing in early 1987; Masters' explosive Four Corners investigative report on police corruption entitled The Moonlight State aired on 11 May 1987.[58] Within a week, Acting Premier Gunn decided to initiate a wide-ranging Commission of Inquiry into police corruption, despite opposition from Bjelke-Petersen. Gunn selected former Federal Court judge Tony Fitzgerald as its head. By late June, the terms of inquiry of what became known as the Fitzgerald Inquiry had been widened from members of the force to include "any other persons" with whom police might have been engaged in misconduct since 1977.[59]

On 27 May 1987, Prime Minister Hawke called a federal election for 11 July, catching Bjelke-Petersen unprepared. The premier had flown to the United States two days earlier and had not yet nominated for a federal seat;[55] on 3 June he abandoned his ambitions to become prime minister and resumed his position in the Queensland government.[59] The announcement came too late for the non-Labor forces, as Bjelke-Petersen had pressured the federal Nationals to pull out of the Coalition. Due to a number of three-cornered contests, Labor won a sweeping victory.

Fitzgerald began his formal hearings on 27 July 1987, and a month later the first bombshells were dropped as Sgt Harry Burgess—accused of accepting $221,000 in bribes since 1981—implicated senior officers Jack Herbert, Noel Dwyer, Graeme Parker and Commissioner Terry Lewis in complex graft schemes. Other allegations quickly followed, and on 21 September Police Minister Gunn ordered Lewis—knighted in 1986 at Bjelke-Petersen's behest[53] and now accused of having taken $663,000 in bribes—to stand down.[59]

The ground had begun to shift out from under Bjelke-Petersen's feet even before the hearings began. The first allegations of corruption prompted the Labor opposition to ask the Governor, Sir Walter Campbell, to use his reserve power to sack Bjelke-Petersen.[60] His position deteriorated rapidly; ministers were openly opposing him in Cabinet meetings, which had been almost unthinkable for most of his tenure.

Throughout 1986, Bjelke-Petersen had pushed for approval of construction of the world's tallest skyscraper in the Brisbane CBD, which had been announced in May. The project, which had not been approved by the Brisbane City Council, enraged his backbenchers. During a party meeting, MP Huan Fraser confronted Bjelke-Petersen, saying "I know there is a bloody big payoff to you coming as a result of this. You're a corrupt old bastard, and I'm not going to cop it."[61][62]

By this time, Sparkes had also turned against Bjelke-Petersen, and was pressuring him to retire. On 7 October, Bjelke-Petersen announced he would retire from politics on 8 August 1988, the 20th anniversary of his swearing-in.[59]

Six weeks later, on 23 November 1987, Bjelke-Petersen visited Campbell and advised him to sack the entire Cabinet and appoint a new one with redistributed portfolios. Under normal circumstances, Campbell would have been bound by convention to act on Bjelke-Petersen's advice. However, Campbell persuaded Bjelke-Petersen to limit his demand to ask for the resignations of those ministers he wanted removed.[63] Bjelke-Petersen then demanded the resignation of five of his ministers, including Gunn and Health Minister Mike Ahern. All refused. Gunn, believing Bjelke-Petersen intended to take over the police portfolio and terminate the Fitzgerald Inquiry, announced he would challenge for the leadership. Bjelke-Petersen persisted regardless and decided to sack three ministers—Ahern, Austin and Peter McKechnie—on the grounds of displaying insufficient loyalty.[53][64]

The next day, Bjelke-Petersen formally advised Campbell to sack Ahern, Austin and McKechnie and call an early election. However, Ahern, Gunn and Austin told Campbell that Bjelke-Petersen no longer had enough parliamentary support to govern. While Campbell agreed to the ouster of Ahern, Gunn and Austin, he was reluctant to call fresh elections for a legislature that was only a year old. He thus concluded that the crisis was a political one in which he should not be involved. He also believed that Bjelke-Petersen was no longer acting rationally. After Bjelke-Petersen refused numerous requests for a party meeting, the party's management committee called one for 26 November. At this meeting, a spill motion was carried by a margin of 38–9. Bjelke-Petersen boycotted the meeting, and thus did not nominate for the ensuing leadership vote, which saw Ahern elected as the new leader and Gunn elected as deputy.[65]

Ahern promptly wrote to Campbell seeking to be commissioned as premier.[66] This normally should have been a pro forma request, given the Nationals' outright majority. However, Bjelke-Petersen insisted he was still premier, and even sought the support of his old Liberal and Labor foes in order to stay in office.[64] However, even with the combined support of the Liberals and Labor plus Bjelke-Petersen's own vote, Bjelke-Petersen would have needed at least four Nationals floor-crossings to keep his post. Despite Bjelke-Petersen's seemingly tenuous position, Campbell had received legal advice that he could sack Bjelke-Petersen only if he tried to stay in office after being defeated in the legislature.[67] This was per longstanding constitutional practice in Australia, which calls for a first minister (Prime Minister at the federal level, premier at the state level, chief minister at the territorial level) to stay in office unless he resigns or is defeated in the House.

The result was a situation in which, as the Sydney Morning Herald put it, Queensland had a "Premier who is not leader" and the National Party a "Leader who is not Premier".[68] The crisis continued till 1 December, when Bjelke-Petersen announced his retirement from politics.[64][69] He declared:

The policies of the National Party are no longer those on which I went to the people. Therefore I have no wish to lead the Government any longer. It was my intention to take this matter to the floor of State Parliament. However, I now have no further interest in leading the National Party any further.[70]

Three months later, Bjelke-Petersen called on voters at the federal by-election in Groom to support the Liberal candidate instead of the National contestant. Bjelke-Petersen said the Nationals had lost their way and turned their backs on traditional conservative policies.[71]

Aftermath: 1988–2003

editIn February 1988, the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal announced a hearing into the suitability of entrepreneur Alan Bond, the owner of the Nine TV network, to hold a broadcasting licence. The investigation centred on the network's $400,000 payout to Bjelke-Petersen in 1985 to settle a defamation action launched by the premier in 1983. Bond had made the payment (negotiated from an initial $1 million claim) soon after buying the network and a major Queensland brewery and claimed in a later television interview that Bjelke-Petersen told him he would need to make the payment if he wished to continue business in Queensland. (In April 1989 the broadcasting tribunal found that Bjelke-Petersen had placed Bond in a position of "commercial blackmail".)[72]

Bjelke-Petersen was called to the Fitzgerald corruption inquiry on 1 December 1988, where he said that, despite allegations raised in the media and parliament, he had held no suspicion in the previous decade of corruption in Queensland. He said a Hong Kong businessman's 1986 donation of $100,000 to an election slush fund—delivered in cash at the premier's Brisbane office—was not unusual, and that he did not know the identity of other donors who had left sums of $50,000 and $60,000 in cash at his office on other occasions. Questioned by barrister Michael Forde, Bjelke-Petersen—whose citation for his 1984 knighthood noted that he was "a strong believer in historic tradition of parliamentary democracy"—was also unable to explain the doctrine of separation of powers under the Westminster system.[73]

Under Ahern (1987–89) and Russell Cooper (1989), the Nationals were unable to overcome the damage from the revelations about the massive corruption in the Bjelke-Petersen government. At the 1989 state election, Labor swept the Nationals from power in a 24-seat swing—at the time, the worst defeat of a sitting government since responsible government was introduced in Queensland.

As a result of the Fitzgerald inquiry, Lewis was tried, convicted, and jailed on corruption charges. He was later stripped of his knighthood and other honours. A number of other officials, including ministers Don Lane and Austin were also jailed. Another former minister, Russ Hinze, died while awaiting trial.

In 1991 Bjelke-Petersen faced criminal trial for perjury arising out of the evidence he had given to the Fitzgerald inquiry (an earlier proposed charge of corruption was incorporated into the perjury charge). Bjelke-Petersen's former police Special Branch bodyguard Sergeant Bob Carter told the court that in 1986 he had twice been given packages of cash totalling $210,000 at the premier's office. He was told to take them to a Brisbane city law firm and then watch as the money was deposited in a company bank account.[citation needed] The money had been given over by developer Sng Swee Lee, and the bank account was in the name of Kaldeal, operated by Sir Edward Lyons, a trustee of the National Party.[74] John Huey, a Fitzgerald Inquiry investigator, later told Four Corners: "I said to Robert Sng, 'Well what did Sir Joh say to you when you gave him this large sum of money?' And he said, "All he said was, 'thank you, thank you, thank you'."[75] The jury could not agree on a verdict. In 1992 it was revealed that the jury foreman, Luke Shaw, was a member of the Young Nationals and was identified with the "Friends of Joh" movement. A special prosecutor announced in 1992 there would be no retrial because Bjelke-Petersen, then aged 81, was too old. Developer Sng Swee Lee refused to return from Singapore for a retrial. Bjelke-Petersen said his defence costs sent him broke.[76]

Bjelke-Petersen's memoirs, Don't You Worry About That: The Joh Bjelke-Petersen Memoirs, were published the same year.[77] He retired to Bethany where his son John and wife Karyn set up bed and breakfast cottages on the property. He developed progressive supranuclear palsy, a condition similar to Parkinson's disease.

In 2003, he lodged a $338 million compensation claim with the Queensland Labor government for loss of business opportunities resulting from the Fitzgerald inquiry. The claim was based on the assertion that the inquiry had not been lawfully commissioned by state cabinet and that it had acted outside its powers. The government rejected the claim; in his advice to the government, tabled in parliament, Crown Solicitor Conrad Lohe recommended dismissing the claim and said Bjelke-Petersen was "fortunate" not to have faced a second trial.[76][78]

Electoral history

edit| Election | Electorate | Votes | % | #[c] | +/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Nanango | 3,733 / 8,962 |

42.04 | 1st of 5 | 42.04 |

| 1950 | Barambah | 6,881 / 9,214 |

75.23 | 1st of 2 | 33.19 |

| 1953 | unopposed | — | |||

| 1956 | |||||

| 1957 | 6,503 / 9,346 |

70.30 | 1st of 2 | 4.93[d] | |

| 1960 | 5,957 / 9,323 |

64.50 | 1st of 3 | 5.8 | |

| 1963 | 5,715 / 9,179 |

62.90 | 1st of 3 | 1.6 | |

| 1966 | 6,659 / 9,009 |

74.20 | 1st of 2 | 11.3 | |

| 1969 | 6,965 / 8,906 |

78.20 | 1st of 2 | 4 | |

| 1972 | 6,249 / 9,272 |

67.40 | 1st of 4 | 10.8 | |

| 1974 | 8,335 / 9,998 |

83.40 | 1st of 2 | 16 | |

| 1977 | 7,707 / 9,843 |

78.30 | 1st of 2 | 5.1 | |

| 1980 | 8,011 / 9,960 |

80.40 | 1st of 3 | 5.1 | |

| 1983 | 8,446 / 10,756 |

78.50 | 1st of 2 | 1.9 | |

| 1986[80] | 9,114 / 11,765 |

77.47 | 1st of 2 | 1.03 | |

Death

editBjelke-Petersen died in St Aubyn's Hospital in Kingaroy on 23 April 2005, aged 94, with his wife and family members by his side. He received a State Funeral, held in Kingaroy Town Hall, at which the then Prime Minister, John Howard, and Queensland Premier, Peter Beattie were speakers.[81]

Beattie, who had been sued by Bjelke-Petersen for defamation and was arrested during the 1971 Springbok tour protests, said: "I think too often in the adversarial nature of politics we forget that behind every leader, behind every politician, is indeed a family and we shouldn't forget that."[82]

As the funeral was taking place in Kingaroy, about 2000 protesters gathered in Brisbane to "ensure that those who suffered under successive Bjelke-Petersen governments were not forgotten". Protest organiser Drew Hutton said "Queenslanders should remember what is described as a dark passage in the state's history."[citation needed]

Bjelke-Petersen was buried "beside his trees that he planted and he nurtured and they grew"[81] at the Kingaroy family property, called "Bethany".

The Bjelke-Petersen Dam in Moffatdale in the South Burnett Region is named after him.[83]

Malapportionment

editBjelke-Petersen's government was kept in power in part due to an electoral malapportionment where rural electoral districts had significantly fewer enrolled voters than those in metropolitan areas. This system was introduced by the Labor Party in 1949 as an overt electoral fix in order to concentrate its base of voters in regional towns and rural areas in as many districts as possible. Under Nicklin the bias in favour of rural constituencies was maintained, but reworked to favour the Country and Liberal parties by carving new Country-leaning seats in the hinterlands of provincial areas and Liberal-leaning seats in Brisbane.

The bias worked to Bjelke-Petersen's benefit in his first election as premier, in 1969. His Country Party won only 21 percent of the primary vote, finishing third behind Labor and the Liberals. However, due to the Country Party's heavy concentration of support in the provincial and rural zones, it won 26 seats, seven more than the Liberals. Combined, the Coalition had 45 seats out of 78, enough to consign Labor to opposition even though it finished percentage points ahead of the Coalition on the two-party vote. While in opposition, Bjelke-Petersen had vehemently criticised the 1949 redistribution, claiming that Labor was effectively telling Queenslanders, "Whether you like it or not, we will be the government."

In 1972, Bjelke-Petersen strengthened the system to favour his own party. To the three existing electoral zones—metropolitan Brisbane, provincial and rural—was added a fourth zone, the remote zone. The seats in this area had even fewer enrolled electors than seats in the rural zone—in some cases, as few as a third of the enrolled electors in a typical Brisbane seat. This had the effect of packing Labor support into the Brisbane area and the provincial cities. On average, it took only 7,000 votes to win a Country/National seat, versus 12,000 for a Labor seat. This gross distortion led to his opponents referring to it as the "Bjelkemander", a play on the term "gerrymander". The 1985 proposal would have made the malapportionment even more severe, to the point that a vote in Brisbane would have only been worth half a country vote. The lack of a state upper house (which Queensland had abolished in 1922) allowed legislation to be passed without the need to negotiate with other political parties.

Character and attitudes

editAuthoritarianism

editQueensland political scientist Rae Wear described Bjelke-Petersen as an authoritarian who treated democratic values with contempt and was intolerant and resentful of opposition, yet who also demonstrated a down-home charm and old-fashioned courtesies as well as kindness to colleagues. Those who worked closely with him described him as stubborn with a propensity to fly into rages in which he would "rant and rave like Adolf Hitler", creating "fantastic performances" as he shook with rage, becoming increasingly incoherent. Many of his National Party colleagues were in terror of him on such occasions.[84] Raised by migrant parents in spartan rural surroundings, he combined a strong work ethic with an ascetic lifestyle that was strongly shaped by his Lutheran upbringing. As a young man Bjelke-Petersen lived alone for 15 years in an old cow bail with a leaky bark roof and only the most basic of facilities. He had a lifelong habit of hard work and long days and while premier often slept for just four hours a night.[citation needed] He valued "the School of Life, the hard knocks of life" more than formal education and showed little respect for academics and universities, although he accepted an honorary doctorate of Laws from the University of Queensland in May 1985, prompting criticism from both students and staff.[85][86] Wear dismissed Bjelke-Petersen's claim that he was a reluctant and accidental entrant into state politics, concluding that he "seized opportunity whenever it presented and held tenaciously to power", and was later willing to use any device to remain premier. She said that although Bjelke-Petersen denied ever knowing anything about corruption, "the evidence suggests this is untrue. He ignored it because to acknowledge its presence was to hand a weapon to his political enemies and because he was prepared to trade off corruption for police loyalty".[87][88]

Biographers have suggested that Bjelke-Petersen, raised under a resented patriarch, himself came to play the strong patriarch, refusing to be accountable to anyone: "Rather than explaining himself or answering questions, he demanded to be taken on trust."[89] He believed God had chosen him to save Australia from socialism[90] and also had a profound sense of Christian conscience that he said guided political decisions, explaining, "Your whole instinct cries out whether it's good or bad." A cousin of Bjelke-Petersen said the premier "has an inner certainty that he knows the answers to our political and social woes" and as a good Christian expected to be trusted, thus needing no constitutional checks and balances.[91]

Relations with the media

editGuided by media adviser Allen Callaghan, with whom he worked from 1971 to 1979, Bjelke-Petersen was an astute manager of news media. He made himself available to reporters and held daily press conferences where he "fed the chooks". Callaghan released a steady stream of press releases, timing them to coincide with periods when news editors were most desperate for news. For most of Bjelke-Petersen's premiership, Queensland newspapers were supportive of his government, generally supporting the police and government on the street march issue, while Brisbane's Courier-Mail endorsed the return of the coalition government at every state election between 1957 and 1986.[92]

According to Rae Wear, Bjelke-Petersen demanded total loyalty of the media and was unforgiving and vindictive if reporting was not to his satisfaction. In 1984, he reacted to a series of critical articles in the Courier-Mail by switching the government's million-dollar classified advertising account to the rival Daily Sun.[92] He banned a Courier-Mail reporter who was critical of his excessive use of the government aircraft and Wear claims other journalists who wrote critical articles became the subject of rumour-mongering, were harassed by traffic police, or found that "leaks" from the government dried up. Journalists covering industrial disputes and picketing were also afraid of arrest. In 1985, the Australian Journalists Association withdrew from the system of police passes because of police refusal to accredit certain journalists.[93] Journalists, editors and producers were also deterred from critical stories by Bjelke-Petersen's increasing use of defamation actions in order to try to "stop talk about a corrupt government". Queensland historian Ross Fitzgerald was threatened with criminal libel in 1984 when he sought to publish a critical history of the state.[94] The premier and his ministers launched 24 defamation actions against the Opposition leader and Labor Party and trade union figures, with 14 of them publicly funded.[92] He saw no role for the media in making government accountable, telling the Australian Financial Review in 1986: "The greatest thing that could happen to the state and the nation is when we get rid of the media. Then we would live in peace and tranquillity and no one would know anything."[92]

Callaghan's advice to Bjelke-Petersen included the recommendation that he maintain his rambling style of communication with mangled syntax, recognising it added to his homespun appeal to ordinary people and also allowed him to avoid giving answers. His catchphrase response to unwelcome queries was, "Don't you worry about that", a phrase that was used as the title of his 1990 memoir.[95] Wear wrote: "His verbal stumbling communicated decent simplicity and trustworthiness and, in order to enhance his popular appeal, Bjelke-Petersen appears to have exaggerated, or at least not tried to rid himself of, his famous speaking style."[92]

Heritage and environment

editThe premier showed little concern for heritage and environmental issues, attracting widespread public fury over the 1979 demolition of Brisbane's historic Bellevue Hotel[96] and favouring oil drilling on the Great Barrier Reef[16] and sand mining on Moreton Island.[97] He opposed the expansion of Aboriginal land rights,[98] barred state officials from meeting World Council of Churches delegates who were studying the treatment of Aborigines in Queensland[97] and demonstrated a strong moralistic streak, banning Playboy magazine, opposing school sex education and condom vending machines and in 1980 proposing a ban on women flying south for abortions.[99] In May 1985 the government conducted a series of raids on so-called abortion clinics.[53]

Industrial relations

editBjelke-Petersen had a confrontational approach to industrial relations. As a backbencher he had made clear his opposition to unions and the 40-hour week[100] and in 1979 he pushed for legislation that would lead to the lifetime loss of a driver's licence for union members using their own vehicles to organise strikes.

For four days in 1981, Queensland power workers had been using rotating blackouts and restrictions as a means of pressure. Bjelke-Petersen responded by closing licensed clubs and hotels and publishing the names and addresses of the 260 involved workers, with the aim of inspiring members of the public to harass them. The intimidation tactic worked and the union resumed normal work schedules within 15 minutes of government ads arriving in Brisbane newspapers. "I believe the Government now knows how in the future to approach such disputes in essential services", said Bjelke-Petersen.[101]

In 1982 he ordered the dismissal of teachers who were conducting rolling stoppages on the issue of class sizes. The same year he invoked the Essential Services Act to declare a state of emergency when government blue-collar workers launched industrial action to support a 38-hour week.

His biggest showdown with unions came in February 1985 when electrical workers, opposing the increasing use of contract labour in their industry, placed a ban on performing routine maintenance. Bjelke-Petersen ordered the shutdown of several of the states generators. That led to two weeks of blackouts. The government declared a state of emergency on 7 February, sacked as many as 1100 striking workers but offered their jobs back if they would sign a no-strike clause and work a 40-hour week; most accepted but 400 lost their jobs and superannuation. Labor compared the government with the Nazi regime, calling the new laws "police-state legislation".[53][102]

Aboriginal people

editBjelke-Petersen believed that he and his government knew what was best for Aboriginal Australians. He excused racially discriminatory legislation as a protective measure and generally supported Aboriginal self-determination at least partly as striking a blow against the monolithic centralism of Canberra under Labor.[103]

In June 1976, Bjelke-Petersen blocked the proposed sale of a pastoral property on the Cape York Peninsula to a group of Aboriginal people, because according to cabinet policy, "The Queensland Government does not view favourably proposals to acquire large areas of additional freehold or leasehold land for development by Aborigines or Aboriginal groups in isolation."[104] This dispute resulted in the case of Koowarta v Bjelke-Petersen, which was decided partly in the High Court in 1982, and partly in the Supreme Court of Queensland in 1988. The courts found that Bjelke-Petersen's policy had discriminated against Aboriginal people.[105]

In 1978, the Uniting Church supported Aborigines at Aurukun and Mornington Island in their struggle with the Queensland Government after it granted a 1900 square kilometre mining lease to a mining consortium under extremely favourable conditions. The Aurukun people challenged the legislation, winning their case in the Supreme Court of Queensland but later losing when the Queensland Government appealed to the Privy Council of the United Kingdom.[106]

Bjelke-Petersen was opposed by Sir Robert Sparkes, church groups and the federal government over a 1982 push to abolish Aboriginal and Islander community reserves and to give title to the reserve lands to local councils elected by communities—titles that could be revoked by the government for unspecified reasons. Bjelke-Petersen claimed there were over-riding issues of defence and security because of fears of a communist plot to create a separate black nation in Australia.[98]

In 1982, Bjelke-Petersen also denied John Koowarta, an Aboriginal Wik man, the sale of the Archer River cattle station that covered large amounts of the Wik ancestral homeland, due to Aboriginal people 'not being allowed to buy large areas of land'. Koowarta appealed the decision to the High Court, arguing that the Queensland Government could not do this under the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth). The High Court overruled Bjelke-Petersen's decision, allowing the Wik nation's traditional land to be bought by Koowarta. The sale was to proceed, but at the last minute, Bjelke-Petersen, in an act described by Australian Conservation Foundation councillor Kevin Guy as one of "spite and prejudice,"[107] declared the Archer River property a national park, the Archer Bend National Park (now known as Oyala Thumotang National Park), to ensure that no one could ever own it. However, on 6 October 2010 Premier Anna Bligh announced that a 75,000 hectares (750 km2) portion of the park would be given over to the Wik-Mungkana peoples as freehold land. On 22 May 2012 Campbell Newman handed the park to the Oyala Thumotang Land Trust representing the Wik Mungkan, Southern Kaanju and Ayapathu and transferred a 75,074 hectares (750.74 km2) portion of land revoked from the park as freehold land.[108][109]

Anti-homosexual remarks

editDuring his period in office Bjelke-Petersen frequently raised fears of a conspiracy of "southern homosexuals" to gain electoral advantage and to oppose the policies of the federal government or other states.[110]

State development

editConsiderable development of the state's infrastructure took place during the Bjelke-Petersen era. He was a leading proponent of Wivenhoe and Burdekin Dams, encouraging the modernising and electrifying of the Queensland railway system, and the construction of the Gateway Bridge.[11] Airports, coal mines, power stations, and dams were built throughout the state. James Cook University was established. In Brisbane, the Queensland Cultural Centre, Griffith University, the Southeast Freeway, and the Captain Cook, Gateway and Merivale bridges were all constructed, as well as the Parliamentary Annexe that was attached to Queensland Parliament House. Bjelke-Petersen was one of the instigators of World Expo 88 (now South Bank Parklands) and the 1982 Brisbane Commonwealth Games.[11]

His government worked closely with property developers on the Gold Coast, who constructed resorts, hotels, a casino and a system of residential developments. In one controversial case, the Queensland government passed special legislation, the Sanctuary Cove Act 1985, to exempt a luxury development, Sanctuary Cove, from local government planning regulations.[111] The developer, Mike Gore, was seen as a key member of the "white shoe brigade", a group of Gold Coast businessmen who became influential supporters of Bjelke-Petersen.[112] The "white-shoe" nickname was a contemptuous allusion to the nouveau riche origins revealed by their gaudy and tasteless choice of clothing, which included brightly coloured or patterned shirts, slacks with white stripes or in pastel shades, and shoes and belts of white leather, these often having gold or gilt buckles. They became known for shady deals with the government concerning property development, often with dire consequences for heritage buildings.[113] A similar piece of legislation was passed to allow a Japanese company, Iwasaki Sangyo, to develop a tourist resort near Yeppoon in Central Queensland.

Personal associations

editHe was an associate of Milan Brych, who had previously been removed from the New Zealand Medical Register for promoting unproven cancer cures.[114][115][116]

References

editNotes

- ^ During Bjelke-Petersen's Premiership, the Country Party changed its name twice: to the National Country Party and later to the National Party.

- ^ Bjelke-Petersen himself pronounced his name /ˈdʒoʊ ˈbjɛlkə ˈpiːtərsən/,[1] with the surname closer to its Danish roots. The Australian public, however, pronounced it /ˈbjɛlki/ or /biˈɛlki/.

- ^ Of candidates running.

- ^ From results in 1950.

Citations

- ^ "A Country Road: The Nationals: Joh Bjelke-Petersen". YouTube. December 2014. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ a b Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (2nd ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 119–123. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ a b Peter Charlton, "Law and order the making of unlikely leader," The Courier-Mail, 25 April 2005, pg 25.

- ^ "Sir Joh, our home-grown banana republican" Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Age, 25 April 2005.

- ^ a b Wear 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Cunneen, Chris; McLeod, E. A. (1979). "Hans Christian Bjelke-Petersen (1872–1964)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 7. Melbourne University Press.

- ^ Wear 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Wear 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Wear 2002, p. 7.

- ^ a b Wear 2002, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b c Mccosker, Malcolm (28 April 2005). "Early business ventures of Bjelke-Petersen in Queensland". Qcl.farmonline.com.au. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "C.P. Candidate For Nanango Seat". The Morning Bulletin. 7 February 1944. p. 1. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016.

Mr J. B. Edwards, the sitting member, was selected as Country Party candidate... by plebiscite held yesterday. His closest opponent was Mr Bjelke-Petersen...

- ^ a b Wear 2002, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Biodata. Bookrags.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ a b c Wear 2002, pp. xiv, 74, 79–82.

- ^ a b c Whitton, Evan (1989). The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia's Police State. Sydney: ABC Enterprises. pp. 12–17. ISBN 0-642-12809-X.

- ^ a b Wear 2002, pp. 93–94.

- ^ a b c d Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (2nd ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 86–94. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ a b Whitton, Evan (1989). The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia's Police State. Sydney: ABC Enterprises. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-642-12809-X.

- ^ Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (Paperback ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ a b Wear 2002, pp. 136–138.

- ^ Springboks "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "Australian Biography: Ray Whitrod". National Film and Sound Archive. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Wear 2002, p. 138.

- ^ ""Study examines Sir Joh's life and times" UQ News Online". Uq.edu.au. 4 June 1999. Archived from the original on 10 December 2010. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (Paperback ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 95–118. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (Paperback ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 162–163. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (Paperback ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 144–163. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (Paperback ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 181–198. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (Paperback ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (Paperback ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 170–180. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ a b c d e Don't you worry about that! – The Joh Bjelke-Petersen Memoirs Archived 18 July 2012 at archive.today (summary), Joh Bjelke-Petersen, 1990. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ a b Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (Paperback ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 199–214. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ Madigan, Michael (17 March 2012). "Queensland Labor barely alive after future leadership decapitated in state election". The Courier-Mail. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ Wear 2002, pp. 141–142.

- ^ a b c d e Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (2nd ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 255–274. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ a b c d Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (2nd ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 320–337. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ a b Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (2nd ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 238–254. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ Wear 2002, p. 201.

- ^ Wear 2002, p. 202.

- ^ Wear 2002, p. 159.

- ^ a b "Colin Lamont, "The Joh Years – Lest We Forget", Online Opinion, 2005". Onlineopinion.com.au. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "Sydney Morning Herald, 2005". Smh.com.au. 25 April 2005. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ a b Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (2nd ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 287–288. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (2nd ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 317–319. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ Whitton, Evan (1989). The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia's Police State. Sydney: ABC Enterprises. pp. 70–71. ISBN 0-642-12809-X.

- ^ a b c d Lunn, Hugh (1987). Joh: The Life and Political Adventures of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen (2nd ed.). Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. pp. 351–76. ISBN 0-7022-2087-6.

- ^ Wear 2002, pp. 165–169.

- ^ It's an Honour Archived 26 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Whitton, Evan (1989). The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia's Police State. Sydney: ABC Enterprises. pp. 91–92. ISBN 0-642-12809-X.

- ^ "Knights, dames – be honest, Australia, you love it". 27 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Wanna, John; Arklay, Tracey (July 2010), "15", The Ayes Have It: The history of the Queensland Parliament, 1957–1989, Canberra: ANU Press, ISBN 9781921666308

- ^ Whitton, Evan (1989). The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia's Police State. Sydney: ABC Enterprises. pp. 100, 114. ISBN 0-642-12809-X.

- ^ a b Wear 2002, pp. 118–121.

- ^ Whitton, Evan (1989). The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia's Police State. Sydney: ABC Enterprises. p. 116. ISBN 0-642-12809-X.

- ^ "Farewell, Sir Joh, the great divider". The Sydney Morning Herald. 25 April 2005. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "The Moonlight State – 11 May 1987". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d Whitton, Evan (1989). The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia's Police State. Sydney: ABC Enterprises. pp. 116–136. ISBN 0-642-12809-X.

- ^ Barlow, Geoff; Corkery, Jim F. (2007). "Sir Walter Campbell: Queensland Governor and his role in Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen's resignation, 1987". Owen Dixon Society eJournal. Bond University. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Knocking off the hillbilly dictator: Joh's corruption finally comes out; Mitchell, Alex; Crikey, 24 September 2015 "Joh Bjelke-Petersen corrupt and criminal, All Fall Down book proves | Crikey". 24 September 2015. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ^ All Fall Down Condon, Matthew; University of Queensland Press, 2015

- ^ Walter Campbell "Letter from Governor Walter Campbell to Premier Bjelke Petersen, 25 November 1987," 1 in Walter Campbell, Johannes Bjelke Petersen & Michael J. Ahern, Copies of correspondence relating to the change-over from the Bjelke-Petersen government to the Ahern government in late 1987. (Brisbane: Queensland Government, 1988).

- ^ a b c Whitton, Evan (1989). The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia's Police State. Sydney: ABC Enterprises. pp. 137–139. ISBN 0-642-12809-X.

- ^ "Australian Political Chronicle: July–December 1987". Australian Journal of Politics and History. 34 (2): 239–240. June 1988. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1988.tb01176.x. ISSN 0004-9522.

- ^ Michael J. Ahern, "Letter from Parliamentary Leader of the State Parliamentary National Party Mike Ahern to His Excellency Governor Walter Campbell on 26 November 1987," in Walter Campbell, Johannes Bjelke Petersen & Michael J. Ahern, Copies of correspondence relating to the change-over from the Bjelke-Petersen government to the Ahern government in late 1987. (Brisbane: Queensland Government, 1988).

- ^ "Memorandum from the Solicitor General, 26 November 1987," Section 7, in Walter Campbell, Johannes Bjelke Petersen & Michael J. Ahern, Copies of correspondence relating to the change-over from the Bjelke-Petersen government to the Ahern government in late 1987 (Brisbane: Queensland Government, 1988).

- ^ Peter Bowers and Greg Roberts, 'Ahern leads, but Joh rules', Sydney Morning Herald, 27 November 1987. Cited in Barlow & Corkery (2007), p.23

- ^ Whitton, Evan. "When the Sunshine State set up a scoundrel trap", The Australian, 12 May 2007

- ^ Political Chronicle (34(2), June 1988)

- ^ "Vote for Libs, says Joh, the Nats are lost", The Courier-Mail, 15 March 1988, pg 2.

- ^ Whitton, Evan (1989). The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia's Police State. Sydney: ABC Enterprises. pp. 99, 107, 146–147, 172. ISBN 0-642-12809-X.

- ^ Whitton, Evan (1989). The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia's Police State. Sydney: ABC Enterprises. pp. 162–185. ISBN 0-642-12809-X.

- ^ "Joh a great servant: jury foreman", Australian 27.042007

- ^ "Australian ABC news coverage of Sir Joh's trial". Abc.net.au. 27 November 1987. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Sir Joh was loathed and loved", The Age, 23 April 2005 Archived 22 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bookrags.com, op cit, supra. Bookrags.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "Sir Joh's compensation claim rejected", The Age, 10 July 2003

- ^ Hughes, CA; Graham, BD (1974). Voting for the Queensland legislative assembly, 1890–1964 (PDF). Australia National University (ANU). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "Barambah – 1986 – Election Archive". abc.net.au. Antony Green. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022.

- ^ a b Tributes, protest mark Sir Joh's funeral, Australian Broadcasting Corporation Archived 21 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tributes, protest mark Sir Joh's funeral". ABC News. 3 May 2005. Archived from the original on 12 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Bjelke-Petersen Dam". Sunwater. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ Wear 2002, pp. 87, 134–5.

- ^ "Police violence in Queensland". Dlibrary.acu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 11 June 2010.