William Turner (1509/10 – 13 July 1568)[1] was an English divine and reformer, a physician and a natural historian. He has been called “the father of English botany”.[2] He studied medicine in Italy, and was a friend of the great Swiss naturalist, Conrad Gessner. He was an early herbalist and ornithologist, and it is in these fields that the most interest lies today.[3] He is known as being one of the first “parson-naturalists” in England.[4]

He first published Libellus de Re herbaria in Latin in 1538, and later translated it into English because he believed herbalists were not sharing their knowledge. Turner's works were condemned under Henry VIII and under Mary Tudor.[2]

Biography

editEarly years

editTurner was born in Morpeth, Northumberland, in or around 1508. His father was probably a tanner of the same name. He studied at Pembroke Hall, Cambridge University, from 1526 to 1533, where he received his B.A. in 1530 and his M.A. in 1533.[5] He was a Fellow and Senior Treasurer of Pembroke Hall, Cambridge. While at Cambridge he published several works, including Libellus de re herbaria, in 1538. He spent much of his leisure in the careful study of plants which he sought for in their native habitat, and described with an accuracy hitherto unknown in England.

In 1540, he began travelling about preaching until he was arrested. After his release, he went on to study medicine in Italy, at Ferrara and Bologna, from 1540 to 1542 and was incorporated M.D. at one of these universities. He married Jane Auder[6] (perhaps a widow of a Mr Cage when they married[citation needed]) who gave birth to a son Peter in 1542. After his death, she remarried Richard Cox, Bishop of Ely.[7]

Career

editAfter completing his medical degree, he became physician to the Earl of Emden. Back in England, he became chaplain and physician to the Duke of Somerset, and through Somerset's influence, he obtained ecclesiastical preferment. The position as Somerset's physician also led to practice among upper society. He was prebendary of Botevant in York Cathedral in 1550, and Dean of Wells Cathedral from 1551 to 1553, where he established a herbal garden.[8] When Mary I of England acceded to the throne, Turner went into exile once again. From 1553 to 1558, he lived in Weißenburg in Bayern and supported himself as a physician. He became a Calvinist at this time, if not before.

After the succession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, Turner returned to England, and was once again Dean of Wells Cathedral from 1560 to 1564. His attempts to bring the English church into an agreement with the reformed churches of Germany and Switzerland led to his suspension for nonconformity in 1564. Turner died in London on 7 July 1568 at his home in Crutched Friars, in the City of London, and is buried in the church of St Olave Hart Street. An engraved stone on the southeast wall of this church commemorates Turner. Thomas Lever, one of the great puritan preachers of the period, delivered the sermon at his funeral.

Quite early in his career, Turner became interested in natural history and set out to produce reliable lists of English plants and animals, which he published as Libellus de re herbaria in 1538. In 1544, Turner published Avium praecipuarum, quarum apud Plinium et Aristotelem mentio est, brevis et succincta historia ("The Principal Birds of Aristotle and Pliny..."), which not only discussed the principal birds and bird names mentioned by Aristotle and Pliny the Elder but also added accurate descriptions and life histories of birds from his own extensive ornithological knowledge. This is the first printed book devoted entirely to birds.[9]

In 1545, Turner published The Rescuynge of the Romishe Fox, and in 1548, The Names of Herbes. In 1551, he published the first of three parts of his famous Herbal, on which his botanical fame rests.

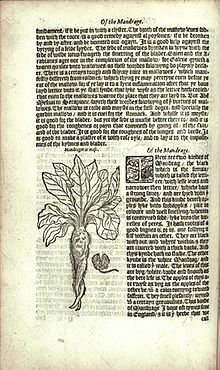

A new herball, wherin are conteyned the names of herbes… (London: imprinted by Steven Myerdman and soolde by John Gybken, 1551) is the first part of Turner's great work; the second was published in 1562 and the third in 1568, both by Arnold Birckman of Cologne. These volumes gave the first clear, systematic survey of English plants, and with their admirable woodcuts (mainly copied from Leonhart Fuchs's 1542 De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes) and detailed observations based on Turner's own field studies put the herbal on an altogether higher footing than in earlier works. At the same time, however, Turner included an account of their "uses and vertues", and in his preface admits that some will accuse him of divulging to the general public what should have been reserved for a professional audience. For the first time, herbal was available in England in the vernacular, from which people could identify the main English plants without difficulty.

A New Book of Spiritual Physick was published in 1555. In 1562, Turner published the second part of his Herbal, dedicated to Sir Thomas Wentworth, son of the patron who had enabled him to go to Cambridge. This book was published by Arnold Birckman of Cologne, and included in the same binding Turner's treatise on baths. The second volume includes one of the earliest reference to the celebrated Glastonbury Thorn, only five miles from Wells, which Turner tells us "is grene all the wynter, as all they that dwell there about do stedfastly holde".[10] The third and last part of Turner's Herbal was published in 1568, in a volume that also contained revised editions of the first and second parts. This was dedicated to Queen Elizabeth. He claimed that the herbal described only English plant species "whereof is no mention made neither of ye old Grecianes nor Latines".[11] A New Boke on the Natures and Properties of all Wines, also published in 1568, had pharmacological intent behind it, as also the included Treatise of Triacle.

As a member of the nonconformist faction in the Vestments controversy Turner was famous for making an adulterer do public penance wearing a square cap and for teaching his dog to steal such caps from bishop's heads. His scholarly pursuits had other, distinctly political, implications. According to Tudor historian Lacey Baldwin Smith, for instance, "Religious discontent and civil rebellion were obviously walking hand in hand when William Turner dared speak out against [Henry VIII's] proclamation of 1543 limiting the reading of the Bible to men of social standing. What kind of ungodly belly wisdom was it, he demanded, to say that 'rich men and the nobles are wiser than the poor people?'"[12]

Turner embraced the transmutation of species. Historian of science Charles E. Raven wrote that "Turner, a shrewd observer and an excellent botanist, accepted transmutation as a commonplace event."[13]

Natural history publications

edit- 1538: Libellus de re herbaria novus. Bydell, London. Index 1878; facsimiles 1877, 1966.

- 1544: Avium praecipuarum, quarum apud Plinium et Aristotelem mentio est, brevis et succincta historia. Gymnicus, Cologne. ed Cambridge 1823; ed with transl. Cambridge 1903.

- 1548: Turner, William (1548). The Names of Herbes (1881 ed.). London: English dialect society.

- 1551: Turner, William (1995) [1562–8]. A New Herball Parts II and III. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44549-8. (Part 1 Mierdman, London 1551; Parts 2 and 3 Barckman, Cologne. 1562, 1568) Parts 1-2, 1551-1562, available at BHL

Other works are listed briefly by Raven.[14]

References

edit- ^ Year of birth from DNB; day of death preferred on grounds of a message sent by the Bishop of Norwich: see Raven p122.

- ^ a b Samson, Alexander. Locus Amoenus: Gardens and Horticulture in the Renaissance, 2012 :4

- ^ Raven, Charles E. 1947. English naturalists from Neckam to Ray: a study of the making of the modern world. Cambridge. p38

- ^ Armstrong, Patrick (2000). The English Parson-naturalist: A Companionship Between Science and Religion. Gracewing. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-85244-516-7.

- ^ "Turner, William (TNR529W)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Richard Cox" 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica Vol. 7

- ^ 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Adler, Mark (May 2010). Mendip Times. pp. 36–37.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "William Turner and the First Bird Book | BirdNote". BirdNote. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ Stout, Adam (2020) Glastonbury Holy Thorn: Story of a Legend Green & Pleasant Publishing, pp. 24-25 ISBN 978-1-9162686-1-6

- ^ Knight, Leah. Of Books and Botany in Early Modern England. p. 40.

- ^ Smith, Henry VIII: The Mask of Royalty, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1971, p. 128.

- ^ Raven, Charles E. (2010 edition). Natural Religion and Christian Theology: Volume 1, Science and Religion: The Gifford Lectures 1951. Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-521-16639-3

- ^ Raven, Charles E. 1947. English naturalists from Neckam to Ray: a study of the making of the modern world. Cambridge. p71

Bibliography

edit- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Hunt, William (1899). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 57. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Jones, W. R. D. "Turner, William (1509/1510-1568)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27874. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

edit- William Turner at the Galileo Project

- William Turner at Morpeth

- Evans AH 1903 Turner on birds. Cambridge University Press.

Historical editions

- Avium praecipuarum quarum apud Plinium et Aristotelem mentio est, ...

- The 1568 edition of the herbal, including part 3. From Rare Book Room.

Modern editions

- George Chapman/Anne Wesencraft/Frank McCombie/Marilyn Tweddle (eds.) William Turner: "A New Herball" Vols 1 and 2: Parts I, II and III. (Cambridge University Press 1996)

- Marie Addyman William Turner: "Father of English Botany" . (Friends of Carlisle Park 2008: Buy it at bookshops in Morpeth, via www.focpMorpeth.org or at Wells Cathedral)

- Works by William Turner at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)