Witness to Murder is a 1954 American film noir crime drama directed by Roy Rowland and starring Barbara Stanwyck, George Sanders, and Gary Merrill. While the film received moderately positive reviews, it ended up as an also-ran to Alfred Hitchcock's somewhat similar Rear Window, which opened less than a month later. The latter picture was a box-office hit.[1]

| Witness to Murder | |

|---|---|

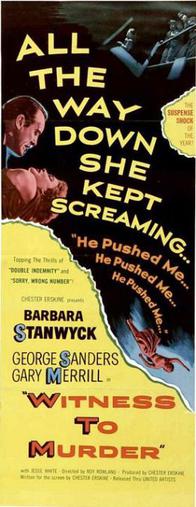

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roy Rowland |

| Screenplay by | Chester Erskine Nunnally Johnson |

| Produced by | Chester Erskine |

| Starring | Barbara Stanwyck George Sanders Gary Merrill |

| Cinematography | John Alton |

| Edited by | Robert Swink |

| Music by | Herschel Burke Gilbert |

Production company | Chester Erskine Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 83 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Plot

editCheryl Draper looks out of her bedroom window, and witnesses a young woman being strangled to death and reports it to the police, but when the killer, Albert Richter, sees detectives arriving downstairs, he moves the body. When the police show up to his door, Albert acts nonchalant, and, when no body is found, the police are convinced that Cheryl dreamt it up.

The next day, Albert puts the body in a trunk and leaves to dispose of it. While he is out, Cheryl notices that an apartment on the same floor is for rent, and she is given a tour by the building manager. She finds torn drapery, which Albert dubiously re-ripped in front of the police, and a pair of earrings. Albert returns and sees Cheryl drive away to the police department with the earrings. He pre-emptively phones the police, and Cheryl is accused of robbery. The two confront each other at the police station, but Albert opts not to press charges. However, the scene leaves Police Lt. Lawrence Mathews suspicious.

Lawrence goes to Cheryl's apartment and tells her that Albert is an ex-Nazi who had been "denazified" and is now an unsuccessful author who is marrying a wealthy heiress. The two meet again when the body of an unidentified woman is found in Griffith Park. Cheryl comes off as conspiratorial and Lawrence believes she is pretending and obsessing about the case; he believes she is telling the truth that she saw something, but does not think what she saw was reality. She is forcibly admitted to an insane asylum after Albert surreptitiously types threatening letters from Cheryl to him to frame her as crazy and a threat to his safety.

After Cheryl is released, Lawrence and a fellow policeman go to the apartment building of the deceased woman (who was revealed to be a Miss Joyce Stewart) to see if anyone there recognizes Albert but no one does, and the police have no case. After Cheryl is released, Albert is at her home and confesses that he killed the woman because she was insignificant to him and he did not want his future wealth to be threatened. However, because she is officially labeled insane by the police and has no credibility, he does not fear admitting anything to her.

Albert later returns to her home with a purported suicide note wherein Cheryl says she will kill herself, and he tries to push her out of her window. Just as he is about to throw her out, a policewoman buzzes at the door and Cheryl flees. She is pursued by Albert, as well as the police, who think she is suicidal. Cheryl runs up a high-rise that is under construction, and gets to the top and is cornered by Albert, and he pushes her off the tower. There are a few construction planks below the precipice onto which she falls and is saved. Lawrence arrives and Albert attempts to push him off as well, but after a brief struggle, it is Albert who falls to his death. Lawrence rescues Cheryl and the police now come to believe her story.

Cast

edit- Barbara Stanwyck as Cheryl Draper

- George Sanders as Albert Richter

- Gary Merrill as Police Lt. Lawrence "Larry" Mathews, also a law student at night school

- Jesse White as Police Sgt. Eddie Vincent

- Harry Shannon as Police Capt. Donnelly

- Claire Carleton as May, The Blonde and a mental patient

- Lewis Martin as Psychiatrist

- Dick Elliott as Apartment Manager

- Harry Tyler as Charlie

- Juanita Moore as Mental Patient

- Joy Hallward as Fellow Worker

- Adeline De Walt Reynolds as The Old Lady

- Claude Akins as Police Officer on guard at the murder victim's apartment (uncredited)

- Sam Edwards as Tommy - Counterman

Critical response

editThe New York Times found the film a "sensitively executed but hardly inspired exercise in premeditated murder....the tension inherent in the search for a murderer is largely lacking in this adventure, which exposes him at the outset to the witness of the title and the audience."[2] The Brooklyn Eagle described the film as a "crime thriller [that] uses effectively the cat-and-mouse technique to tighten tension. As an excitement-creator, it's above average....There are holes in the story, but it's exciting enough to make anyone disregard them."[3] Columnist Jimmie Fidler opined that "Director Roy Rowland has concentrated the story development on suspense, and every foot of the film yields something to that effort" and that all three principal actors "score with convincing performances"[4] Film critic Dennis Schwartz, writing in 2000, appreciated the work of cinematographer John Alton but gave the film a mixed review, writing, "The camerawork of John Alton is the star of this vehicle. His camerawork sets a dark mood of the Los Angeles scenario, escalating the dramatics with shadowy building shots. The twist in the story is that as upstanding a citizen as Stanwyck is, the authorities still side with the Nazi Sanders because he has a higher status. The noir theme of alienation is richly furnished. But the rub is in the story's credibility— Stanwyck was just too strong a character to be so completely victimized."[5]

Adaptations

editWitness to Murder was featured on Lux Video Theatre in January 1956, starring Audrey Totter, Onslow Stevens and Paul Langton in the leading roles.[6][7]

References

edit- ^ Witness to Murder at IMDb.

- ^ "At the Holiday." New York Times, 16 April 19544.

- ^ Corby, Jane. "Barbara Stanwyck Starred in Holiday's Suspense Film." Brooklyn Eagle, 16 April 1954.

- ^ Fidler, Jimmie. "Views of Hollywood." Vallejo (CA) Valley Times, 27 April 1954.

- ^ Dennis Schwartz Movie Reviews film review, August 5, 2019. Accessed: December 18, 2023.

- ^ "Witness to Murder". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- ^ Lux Video Theatre, episode "Witness to Murder" at IMDb

External links

edit- Witness to Murder at IMDb

- Witness to Murder at AllMovie

- Witness to Murder at the TCM Movie Database

- Witness to Murder at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Witness to Murder informational site by Mark Fertig

- Witness to Murder film scene on YouTube