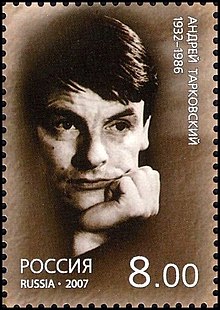

Andrei Tarkovsky (1932–1986)[1] was a Soviet filmmaker who is widely regarded as one of the greatest directors of all time.[2][3] His films are considered Romanticist and are often described as "slow cinema", with the average shot-length in his final three films being over a minute (compared to seconds for most modern films).[4] In his thirty-year career, Tarkovsky directed several student films and seven feature films,[3] co-directed a documentary, and wrote numerous screenplays. He also directed a stage play and wrote a book.

Born in the Soviet Union, Tarkovsky began his career at the State Institute of Cinematography, where he directed several student films.[5] In 1956, he made his directorial debut with the student film The Killers, an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway's eponymous short story.[6] His first feature film was 1962's Ivan's Childhood, considered by some to be his most conventional film.[7] It won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.[8] In 1966, he directed the biopic Andrei Rublev, which garnered him the International Critics' Prize at the Cannes Film Festival.[9]

In 1972, he directed the science fiction film Solaris, which was a response to what Tarkovsky saw as the "phoniness" of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).[10] Solaris was loosely based on the novel of the same title by Stanislaw Lem and won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival.[11][12] His next film was Mirror (1975). In 1976, Tarkovsky directed his only play—a stage production of William Shakespeare's Hamlet at the Lenkom Theatre. Viewing Tarkovsky as a dissident, Soviet authorities shut down the production after only a few performances.[13] His final film produced in the Soviet Union, Stalker (1979), garnered him the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury at Cannes.[14]

Tarkovsky left the Soviet Union in 1979 and directed the film Nostalghia and the accompanying documentary Voyage in Time.[15] At the Cannes Film Festival, Nostalghia was awarded the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury but was blocked from receiving the Palme d'Or by Soviet authorities.[16] In 1985, he published a book, Sculpting in Time, in which he explored art and cinema.[17] His final film, The Sacrifice (1986), was produced in Sweden, shortly before his death from cancer. The film garnered Tarkovsky his second Grand Prix at Cannes, as well as a second International Critics' Prize, a Best Artistic Contribution, and another Prize of the Ecumenical Jury.[18] He was posthumously awarded the Lenin Prize in 1990, the most prestigious award in the Soviet Union.[19]

Filmography

edit| Year | Title | Credited as | Notes | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Director | Writer | ||||

| 1956 | The Killers | Yes | Yes | Student film, also actor, co-directed with Aleksandr Gordon and Marika Beiku, co-written with Gordon | [6][21] |

| 1959 | There Will Be No Leave Today | Yes | Yes | Student film, co-directed with Aleksandr Gordon, co-written with Gordon and Irina Makhovaya | [22] |

| 1960 | The Steamroller and the Violin | Yes | Yes | Student film | [23] |

| 1962 | Ivan's Childhood | Yes | No | [24] | |

| 1966 | Andrei Rublev | Yes | Yes | [25] | |

| 1968 | Sergey Lazo | No | Yes | Also an uncredited acting role | [26][27] |

| 1969 | One Chance in One Thousand | No | Yes | Co-written with Artur Makarov | [27] |

| 1970 | The End of Ataman | No | Yes | Co-written with Andrei Konchalovsky & Eduard Tropinin | [28] |

| 1972 | Solaris | Yes | Yes | [10] | |

| 1973 | The Ferocious One | No | Yes | Co-written with Andrei Konchalovsky & Eduard Tropinin | [29] |

| 1974 | Sour Grape | No | Yes | Co-written with Ruben Ovsepyan | [30] |

| 1975 | Mirror | Yes | Yes | [31] | |

| 1979 | Stalker | Yes | No | [32][33] | |

| Look Out, Snake! | No | Yes | [34] | ||

| 1983 | Nostalghia | Yes | Yes | Co-written with Tonino Guerra | [35][36] |

| 1983 | Voyage in Time | Yes | Yes | Documentary, co-written and co-directed with Tonino Guerra | [37] |

| 1986 | The Sacrifice | Yes | Yes | [38] | |

Unfilmed scripts

edit| Year written | Film | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| 1975 | Hoffmanniana | [9] |

| 1978 | Sardor | [39] |

| 1981 | The Witch | [39] |

Theatrical productions

edit| Year | Play | Location | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Hamlet | Lenkom Theatre, Moscow | [9][13] |

Bibliography

edit| Year | Book title | Translator | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Sculpting in Time | Kitty Hunter-Blair | [17] |

References

edit- ^ Goodman, Walter (30 December 1986). "Andrei Tarkovsky, Director and Soviet Emigre, Dies at 54". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter; Hans, Simran; Bray, Catherine; Leigh, Danny (9 July 2022). "If you watch only one film … the greatest movies by the greatest directors". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ a b Gray, Carmen (27 October 2015). "Where to begin with Andrei Tarkovsky". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Ross, Alex (8 February 2021). "The Drenching Richness of Andrei Tarkovsky". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "Andrei Tarkovsky's Very First Films: Three Student Films, 1956-1960". Open Culture. 7 June 2012. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ a b Jones, J.R. (30 July 2015). "How one Hemingway short story became three different movies". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1 September 2002). "One Day in the Life of Andre Arsenevich". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ "Return to Childhood". Criterion. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Dunne (2008), p. 429.

- ^ a b Shave, Nick (1 May 2020). "I've never seen … Solaris". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Bose, Swapnil Dhruv (30 October 2020). "The reason why Stanisław Lem was furious about Andrei Tarkovsky's adaptation of his novel 'Solaris'". Far Out Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 May 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ "Solaris". Festival de Cannes. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Katya Kompaneyets and Tengiz Mirzashvili sketches for Andrey Tarkovsky's Hamlet". Hesburgh Libraries. University of Notre Dame. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "Stalker: Awards and Festivals". MUBI. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Dunne (2008), p. 169.

- ^ Hoberman, J. (24 January 2014). "Andrei Tarkovsky's 'Nostalghia' on Blu-ray". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ a b Robinson, Harlow (19 July 1987). "Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "All Masterpieces of Andrei Tarkovsky will be Shown at the SIFF". Shanghai International Film Festival. 29 March 2016. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Dunne (2008), p. 431.

- ^ Sushytska (2014), p. 41.

- ^ Hoberman, J. (30 July 2015). "Facing Death With a Shrug in Two Versions of 'The Killers'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "There Will Be No Leave Today". MUBI. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ Goodman, Walter (22 April 1988). "'Steamroller and Violin,' Tarkovsky's Earliest". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (19 May 2016). "Ivan's Childhood review – audacious, coldly lucid postwar Russian classic". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Rose, Steve (20 October 2010). "Andrei Rublev: the best arthouse film of all time". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Sergey Lazo". Letterboxd. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ a b Dunne (2008), p. 428.

- ^ "The End of Ataman". MUBI. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "The Fierce One". Letterboxd. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "Sour Grape". Letterboxd. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "The Mirror". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Le Fanu, Mark (18 July 2017). "Stalker: Meaning and Making". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Dyer, Geoff (5 February 2009). "Danger! High-radiation arthouse!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Riley (2007), p. 24.

- ^ "Nostalgia". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Hoberman, J. (24 January 2014). "A Man Without a Nation, in Italy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Tempo Di Viaggo". Festival de Cannes. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (21 November 1986). "The Sacrifice". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ a b Dunne (2008), p. 430.

Works cited

edit- Dunne, Nathan, ed. (2008). Tarkovsky. Black Dog. ISBN 9781906155049.

- Johnston, Vida T.; Petrie, Graham (1994). The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue. Indiana University Press. pp. 63, 315–318. ISBN 0253208874.

- Riley, John A. (2017). "Hauntology, Ruins, and the Failure of the Future in Andrei Tarkovsky's Stalker". Journal of Film and Video. 69 (1). University of Illinois Press: 18–26. doi:10.5406/jfilmvideo.69.1.0018. S2CID 194435428.

- Totaro, Donato (Spring 1992). "Time and the Film Aesthetics of Andrei Tarkovsky". Revue Canadienne d'Études cinématographiques/Canadian Journal of Film Studies. 2 (1): 21–30. doi:10.3138/cjfs.2.1.21. JSTOR 24402079.

- Sushytska, Julia (Spring 2015). "Tarkovsky's Nostalghia: A Journey to the Home That Never". The Journal of Aesthetic Education. 49 (1): 36–43. doi:10.5406/jaesteduc.49.1.0036. JSTOR 10.5406/jaesteduc.49.1.0036. S2CID 190401817.