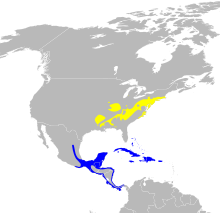

The worm-eating warbler (Helmitheros vermivorum) is a small New World warbler that breeds in the Eastern United States and migrates to southern Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central America for the winter.

| Worm-eating warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Helmitheros Rafinesque, 1819 |

| Species: | H. vermivorum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Helmitheros vermivorum (Gmelin, JF, 1789)

| |

| |

| Range Breeding range Winter range

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Helmitheros vermivorus | |

Taxonomy

editThe worm-eating warbler was formally described in 1789 by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in his revised and expanded edition of Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae. He placed it with the wagtails in the genus Motacilla and coined the binomial name Motacilla vermivora.[3] Gmelin based his account on the "worm-eater" that had been described and illustrated in 1760 by the English naturalist George Edwards in his Gleanings of Natural History. Edwards had received a specimen from the American naturalist William Bartram that had been collected in Pennsylvania.[4] The worm-eating warbler is now placed in the genus Helmitheros that was introduced in 1819 by the French polymath Constantine Samuel Rafinesque.[5][6] The genus name combines the Ancient Greek helmins meaning "worm", and -thēras meaning "hunter". The specific epithet vermivorum is from Latin vermis meaning "worm" and -vorus meaning "-eating".[7] The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[6]

Description

editThe worm-eating warbler is a small New World warbler. It is around 13 cm (5.1 in) in length and weighs 11.8–17.4 g (0.42–0.61 oz).[8] It is relatively plain with olive-brown upperparts and light-coloured underparts, but has black and light brown stripes on its head. It has a slim pointed bill and pink legs. In immature birds, the head stripes are brownish. The male's song is a short high-pitched trill. This bird's call is a chip or tseet. Worm-eating warblers are sexually monomorphic.[9] Males and females can only reliably be sexed during the breeding season by the presence of a brood patch in females or a cloacal protuberance in males. These birds are also difficult to age. Hatch year/second year birds have rusty tips on tertials that wear off by March of the following year. Juveniles can be distinguished by duskier head markings, and cinnamon wingbars.

Distribution and habitat

editThese birds breed in the Eastern United States. Their selected habitats vary significantly between populations.[10] In much of their range, worm-eating warblers are associated with mature hardwood forests on steep slopes. However, recent attention has been focused on coastal breeding populations, as little is known about their ecology or status. Historically, coastal populations would select for pocosin ecosystems. More recently, however, these populations have shifted to frequent use of pine plantations. Current use of pine plantations has resulted in densities higher than in areas previously thought to be their natural habitat. This shift in habitat selection likely demonstrates that worm-eating warblers are more closely associated with shrub structure than stand age or size. If this is the case, the landscape changes that occurred on the Atlantic coastal plain may have had less of an impact on these birds than previously described. Maintaining this species habitat may require managing for dense shrubby midstory and understory. Due to their reliance on shrub structure for foraging, and ground nesting behavior, frequent fires have a negative impact on this species.[11] Other management strategies that reduce the shrub mid-story, increase herbaceous growth, and decrease canopy cover are likely to have a similar effect. More information is needed about their breeding habits in coastal regions as these forests are likely to represent different conditions from their inland counterparts.[12] Fat deposits play a key role in allowing for long distance migration in most passerines. Stopover habitat, or areas that allow birds to replenish their fat stores, are also critical.[13]

In winter, these birds migrate to southern Mexico, the Greater Antilles, and Central America particularly along the Caribbean Slope where they occupy both scrub and moist forests.[14] Worm-eating warblers have disappeared from some parts of their range due to habitat loss but their ability to use both scrub and moist forest ecosystems may be beneficial to the long term conservation of this species.[15]

Behaviour and ecology

editBreeding

editThis bird breeds in dense deciduous forests in the eastern United States, usually on wooded slopes. The nest is an open cup placed on the ground, hidden among dead leaves. It is one of several species of new-world warblers that nests on the ground including the black-and-white warbler (Mniotilta varia), the ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapilla), the northern waterthrush (Parkesia noveboracensis), Louisiana waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla), palm warbler (Setophaga palmarum), and the Kentucky warbler (Geothlypis formosa). The female lays four or five eggs. Both parents feed the young; they may try to distract predators near the nest by pretending to be injured. Worm-eating warblers are often parasitized by brown-headed cowbirds (Molothrus ater) where forest fragmentation occurs.[16] Reducing forest fragmentation may prove vital if populations of worm-eating warblers suffer large declines.

Food and feeding

editThe diet of worm-eating warblers varies across habitat types.[17] This variation can be attributed to different predator avoidance strategies employed by common prey items. On their breeding grounds, worm-eating warblers glean mostly from live foliage, searching for arthropods. On the wintering grounds, this species gleans insects almost exclusively from dead plant material. The name "worm-eating" refers to the numerous Lepidopteran larvae that this species consumes; they rarely if ever eat earthworms.

Use of pesticides, especially those broadcast over a wide area, is likely to have an effect on most insectivorous songbird species, including the worm-eating warbler.[18] These pesticides decrease the species' primary food source and could result in long-term toxicity.

References

edit- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Helmitheros vermivorum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22721768A94730556. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22721768A94730556.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Helmitheros vermivorum". Avibase.

- ^ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 2 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. pp. 951–952.

- ^ Edwards, George (1760). Gleanings of Natural History, Exhibiting Figures of Quadrupeds, Birds, Insects, Plants &c (in English and French). Vol. 2. London: Printed for the author. pp. 200–202, Plate 305.

- ^ Rafinesque, Constantine Samuel (1819). "Prodrome. De 70 nouveaux Genres d'Animaux découverts dans l'intérieur des États-Unis d'Amérique, durant l'année 1818". Journal de Physique de Chimie et d'Histoire Naturelle et des Arts. 88: 417-429 [418].

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2023). "New World warblers, mitrospingid tanagers". IOC World Bird List Version 13.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 188, 400. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Curson, J.M. (2010). "Family Parulidae (New World warblers)". In del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Christie, D.A. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 15: Weavers to New World Warblers. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. pp. 666–800 [765]. ISBN 978-84-96553-68-2.

- ^ Pyle, Peter (1997). Identification guide to North American Birds. Bolinas, California: Slate Creek Press. pp. 499–500.

- ^ Watts, Bryan D.; Michael D. Wilson (2005). "The use of pine plantations by worm-eating warblers in coastal North Carolina". Southeastern Naturalist. 4 (1): 177–187. doi:10.1656/1528-7092(2005)004[0177:tuoppb]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Artman, Vanessa L.; Sutherland, Elaine K.; Downhower, Jerry F. (2008). "Prescribed burning to restore mixed-oak communities in southern Ohio: Effects on breeding bird populations". Conservation Biology. 15 (5): 1423–1434. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2001.00181.x.

- ^ Pitts, Irvin. "The Status and Breeding Habits of the Worm-eating Warbler in South Carolina" (PDF). Carolinabirdclub.org. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Moore, F.; P. Kerlinger (1987). "Stopover and fat deposition by North American wood warblers (Parulinae) following spring migration over the Gulf of Mexico". Oecologia. 74 (1): 47–54. Bibcode:1987Oecol..74...47M. doi:10.1007/bf00377344. PMID 28310413. S2CID 3235707.

- ^ Vitz, Andrew C.; Lise A. Hanners; Stephen R. Patton (2013). "Worm-eating Warbler (Helmitheros vermivorum)". The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.367. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Robbins, C.S.; J R Sauer; R. S. Greenberg; S. Droege (1989). "Population declines in North American birds that migrate to the neotropics". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 86 (19): 7658–7662. Bibcode:1989PNAS...86.7658R. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.19.7658. PMC 298126. PMID 2798430.

- ^ Robinson, Scott K.; Thompson III, Frank R.; Donovan, Therese M.; Whitehead, Donald R.; Faaborg, John (March 31, 1995). "Regional forest fragmentation and the nesting success of migratory birds" (PDF). Science. 267 (5206): 1987–1990. Bibcode:1995Sci...267.1987R. doi:10.1126/science.267.5206.1987. PMID 17770113. S2CID 23144697. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Greenburg, Russell (1987). "Seasonal foraging specialization in the Worm-eating Warbler". Condor. 89 (1): 158–168. doi:10.2307/1368770. JSTOR 1368770.

- ^ Moulding, Jonathon (1976). "Effects of a low-persistence insecticide on forest bird populations". The Auk. 93 (4): 692–708. JSTOR 4084999.

External links

edit- Species account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Species account - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification