Xevious[a] is a vertically scrolling shooter arcade video game developed and published by Namco in 1982. It was released in Japan by Namco and in North America by Atari, Inc. Controlling the Solvalou starship, the player attacks Xevious forces before they destroy all of mankind. The Solvalou has two weapons at its disposal: a zapper to destroy flying craft, and a blaster to bomb ground installations and enemies. It runs on the Namco Galaga arcade system.

| Xevious | |

|---|---|

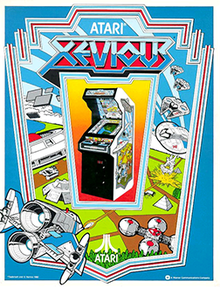

North American arcade flyer | |

| Developer(s) | Namco |

| Publisher(s) |

|

| Designer(s) | Masanobu Endō Shigeki Toyama |

| Artist(s) | Hiroshi Ono[2] |

| Composer(s) | Yuriko Keino |

| Series | Xevious |

| Platform(s) | Arcade, Apple II, Atari 7800, Atari ST, NES, Famicom Disk System, Commodore 64, Amstrad CPC, X68000, ZX Spectrum, Mobile phone, Game Boy Advance, Xbox 360 |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Scrolling shooter |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

| Arcade system | Namco Galaga |

The game was designed by Masanobu Endō and a small team. Created to rival the success of Scramble, it was originally themed around the Vietnam War and titled Cheyenne. Endō wanted the game to have a detailed, integral storyline and a comprehensive world, and to be welcoming for newer players. Several enemies and characters were made to pay homage to other popular science fiction works, including Star Wars, UFO, Alien, and Battlestar Galactica.

Xevious was praised for its detailed graphics, challenge, and originality. It became an unprecedented success for Namco in Japan, with record-breaking sales figures making it the biggest game since Space Invaders. The North American release paled in comparison, despite still selling 5,295 arcade units by the end of 1983. It has been listed among the greatest video games of all time and one of the most influential games in the shoot 'em up genre, establishing the template for vertically scrolling shooters and inspiring games such as TwinBee and RayForce. It was ported to home systems, followed by several sequels and spin-offs, and is included in many Namco compilations.

Gameplay

editXevious is a vertically scrolling shooter. The player controls a flying attack craft, the Solvalou, to destroy the Xevious forces plotting to take over Earth.[3] The Solvalou has two weapons: a zapper that fires projectiles at flying enemies[4] and a blaster for bombing ground installations and vehicles.[4] A reticle in front of the ship shows where bombs will land.[4]

The game has a total of 16 connected areas, which loop back to the first after completing them all.[3] Dying about 70% through starts the player at the beginning of the next.[5] Areas are geographically distinct, with features such as forests, roads, rivers, and mechanical structures. Certain areas have Nazca lines placed on the ground, some in the "condor" design.[5]

The game becomes progressively more difficult as the player becomes more skilled. Once the player does well at destroying a certain enemy type, a more advanced enemy type replaces it.[5] Destroying flashing-red "Zolback" radars found on the ground will cause the game to switch back to easier enemies.[5][3]

Certain points in the game have a fight against the Andor Genesis mothership, which launch an endless stream of projectiles and explosive black spheres known as "Zakatos".[4] The player can either destroy all four blaster receptacles or the core in the center to defeat it.[4] Some parts of the game have hidden towers ("Sol Citadels"), which can be found by bombing specific parts of an area.[3] The Solvalou's bomb reticle flashes red when over one.[3] Yellow "Special Flags" from Namco's own Rally-X are found in a semi-random section of the area. Collecting one gives an extra life.[3]

Development

editXevious was designed by Masanobu Endō, who joined Namco in April 1981 as a planner.[6] He and a small team were assigned by Namco's marketing department to create a two-button scrolling shooter that could rival the success of Konami's arcade game Scramble (1981).[6] Early versions of the game were named Cheyenne and took place during the Vietnam War, with the player controlling a helicopter to shoot down enemies.[6] (The original name may refer to the Vietnam-era Lockheed AH-56 Cheyenne advanced attack helicopter project.) After the development team was reshuffled and the project planner quit altogether, Endō became the head designer for the game.[6] He learned programming on the job during production.[6]

Endō wanted the game to have a consistent, detailed world with a story that didn't feel like a "tacked-on extra", instead being an integral part of the game.[6] The goal of the project was for the game to be inviting for newer players, and to become gradually more difficult as they became better at the game.[6] Influenced by ray-tracing, Endō wanted the game's sprites to be high-quality and detailed, while also making sure they fit the limitations of the arcade board it ran on.[6] The team used a method that involved giving each sprite different shades of gray, allowing sprites to display additional colors.[6] Many of the sprites were designed by Endō himself, although some were done by Hiroshi "Mr. Dotman" Ono, including the player and the background designs.

Many of the game's characters and structures were designed and refined by Shigeki Toyama, who previously worked on many of Namco's robotics for their amusement centers in the early 1980s.[7] The player's ship, the Solvalou, is based on the Nostromo space tug from Alien, while several of the enemies are homages to starships from popular science fiction works, including Star Wars, UFO and Battlestar Galactica.[7]

Concept art for the Andor Genesis mothership depicted it with a more circular design, nicknamed "Gofuru" due to it bearing resemblance to gofuru cookies.[b][7] The design was changed to instead be the shape of an octagon as the hardware had difficulty displaying round objects, while still keeping much of its key features such as the central core and blaster receptacles.[7] Endō created a fictional language during development called "Xevian" that he used to name each of the enemies.[6]

The blaster target for the Solvalou, which flashes red when over an enemy to signal the player to fire a bomb at it, was added to make it easier to destroy ground targets.[6] While programming it, Endō thought it would be interesting to have the blaster target flash over a blank space where an enemy wasn't present, leading to the addition of the Sol citadels.[6] Namco executives expressed displeasure towards the idea, with Endō instead claiming they were simply a bug in the program and leaving them in the code.[6]

The Special Flag icons from Rally-X were added due to Endō being a fan of the game.[6] The game was originally named Zevious, the "X" being added to make it sound more exotic and mysterious, with the metallic logo paying homage to the pinball table Xenon.[6] Location testing for Xevious was conducted in December 1982, and the game was released in Japan in January 1983.[8][9] In the months following, Atari, Inc. acquired the rights to manufacture and distribute it in North America, advertising it as "the Atari game you can't play at home".[5]

Ports

editThe first home conversion of Xevious was for the Family Computer in 1984, being one of the system's first third-party titles. Copies of the game sold out within three days, with Namco's telephone lines being flooded with calls from players in need of gameplay tips.[10] The Famicom version was released internationally for the Nintendo Entertainment System by Bandai, in North America and PAL regions. A version for the Apple II was released the same year. A Commodore 64 version was published by U.S. Gold and released in 1987.[11] Atari, Inc. published an Atari 7800 version as one of the system's 13 launch titles in 1984.[12] The Famicom version was re-released as a budget title for the Famicom Disk System in 1990.[13] Versions for the Atari 2600 and Atari 5200 were completed but never released.[14] The Atari 2600 port was programmed by Tod Frye.[15]

Three mobile phone versions were released; the first for J-Sky in 2002, renamed Xevious Mini, the second for i-Mode the same year, and the third for EZweb in 2003. The NES version was re-released for the Game Boy Advance in 2004 as part of the Classic NES Series line. The arcade version was released for the Xbox 360 in 2007, featuring support for achievements and online leaderboards.[16] The Wii Virtual Console received the NES version in 2006 and the arcade version in 2009.[17]

A remake for the Nintendo 3DS was released in 2011 as part of the 3D Classics series, named 3D Classics: Xevious, which took advantage of the handheld's 3D screen technology.[18] The NES version was released for the Wii U Virtual Console in 2013, and was also added to the Nintendo Switch Online service in March 2023.[19] The arcade version, along with Pac-Man, was released for the Nintendo Switch and PlayStation 4 as part of Hamster's Arcade Archives line in 2021.[20]

Xevious is included in Namco compilations including Namco Museum Vol. 1 (1995), Namco Museum Battle Collection (2005),[21] Namco Museum 50th Anniversary (2005),[22] Namco Museum Remix (2006), Namco Museum DS (2007), Namco Museum Virtual Arcade (2008),[23] and Namco Museum Essentials (2009).[24] The PlayStation home port of Xevious 3D/G includes the original Xevious as an extra, alongside its sequels Super Xevious and Xevious Arrangement.[25] It is included as one of the five titles in Microsoft Revenge of Arcade, released for Windows in 1998.[26] The 2005 GameCube game Star Fox: Assault includes the NES version as an unlockable extra, awarded by collecting all silver medals in the game.[27] For the game's 30th anniversary in 2012, it was released for iOS devices as part of the Namco Arcade compilation.[28]

Reception

edit| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | ARC: [29] NES: [30] Atari 7800: [31] |

| IGN | XBLA: 6/10[32] |

| Your Sinclair | ZX: 8/10[11] |

| Commodore User | C64: 6/10[33] |

| Nintendojo | GBA: 7.5/10[34] |

The arcade game received positive reviews upon release.[33] Computer & Video Games magazine praised the game's thrilling action and impressive graphics, recommending it to players fond of titles such as Zaxxon and Scramble,[35] while Electronic Games found that the realistic graphics and intense action made Xevious an easy recommendation to fans of the genre. Joystik stated that the game was superior to titles Zaxxon and Tron, specifically in its graphics and gameplay.[36]

Amusement Life praised its detailed backgrounds, fast-paced gameplay and sense of mystery, labeling it a masterpiece and one of the best games of 1983.[37] In 1998, Allgame called it one of the more "polite" shoot'em ups for its detailed visuals, challenge and unique enemy designs, finding it to have a "charm" unmatched by other games of the genre.[29]

Home versions of Xevious received praise for their faithfulness to the original. Your Sinclair commended the ZX Spectrum version's accurate conversion of the arcade original, while also praising its fast-paced gameplay and "enthralling" experience.[11] Nintendojo greatly praised the Classic NES Series version for its gameplay and multiplayer mode, favorably comparing it to games such as Gradius.[34] They felt that its responsive controls and "chaotic" difficulty made it one of the best titles released under the label.[34]

Some home releases were met with a more mixed reception for their overall quality and lack of bonus features. Reviewing the Nintendo Entertainment System release, German publication Power Play found the game to be "too old", suggesting that readers instead try out titles such as Gradius.[38] They also disliked the game's lack of power-ups and for areas being too long.[38] GameSpot applauded the Xbox 360 digital version's emulation quality and usage of online leaderboards,[39] but IGN and GameSpot both disliked the lack of improvements made over previous home releases and bonus content.[32][39]

Retrospectively, Xevious has been seen as the "father" of vertical-scrolling shooters and one of the most influential and important games of the genre. In 1995, Flux magazine rated the game 88th on their Top 100 Video Games writing: "Xevious ushered in a new age of scrolling overhead shooters in 1984 with its detailed graphics, multi-level targets and catchy theme music."[40] In 1996, Next Generation ranked it at #90 in their "Top 100 Games of All Time", praising its art direction, intense gameplay and layer of strategy.[41] Gamest magazine ranked it the second greatest arcade game of all time in 1997 based on reader vote, applauding its pre-rendered visuals, addictive nature and historical significance.[42]

Japanese publication Yuge found the Famicom home port to be one of the system's best and most memorable titles for its faithful portrayal of the original.[43] Hardcore Gaming 101 applauded the game for setting up the template for future games of the genre, namely TwinBee, RayForce and Raiden DX.[5] They also praised the game's detailed graphics, difficulty and impressive enemy intelligence for the time.[5] IGN labeled it the 9th greatest Atari 7800 game of all time for its gameplay and overall quality.[44]

Commercial performance

editXevious was an unprecedented success for Namco in Japan. In its first few weeks on the market, it recorded record-breaking sales figures that hadn't been seen since Space Invaders in 1978.[45] It was the top-grossing table arcade cabinet on Japan's Game Machine arcade charts in November 1983.[46] In North American arcades, it was a more moderate success, reaching number-four on the Play Meter arcade charts in July 1983.[47] Atari sold 5,295 arcade cabinets in the US by the end of 1983, earning about $11.1 million (equivalent to $34 million in 2023)[48] in US cabinet sales revenue.[49]

The Famicom version became the console's first killer app with over 1.26 million copies sold in Japan,[50] jumping system sales by nearly 2 million units.[43] The game's immense popularity led to high score tournaments being set up across the country, alongside the creation of strategy guidebooks that documented much of its secrets and hidden items.[51] The NES version went on to sell 1.5 million game cartridges worldwide.[52]

Legacy

editBubble Bobble creator Fukio Mitsuji and Rez producer Tetsuya Mizuguchi cite Xevious as having a profound influence on their careers.[53][54]

Xevious is credited as one of the first video games to have a boss fight,[42][5] pre-rendered graphics[41] and a storyline.[42] In 1985, Roger C. Sharpe of Play Meter magazine stated that the "dimensionalized, overhead perspective of modern, detailed graphics was launched with Xevious."[55]

Sequels and spin-offs

editSuper Xevious was released in 1984. The difficulty was increased to appeal to more advanced players, alongside new enemy types and characters that reset the player's score when shot.[5] A similarly titled game was released in 1986 for the Family Computer, Super Xevious: GAMP no Nazo, which intermixed puzzle elements with the standard Xevious gameplay.[56] An arcade version of this game was also released, known as Vs. Super Xevious, running on the Nintendo Vs. arcade system.[57] An arcade spin-off title starring one of the enemies from Xevious, Grobda, was released in 1984.[58]

Two games for the MSX2 and PC-Engine were released in 1988 and 1990 respectively - Xevious Fardraut Saga and Xevious Fardraut Densetsu,[59] both of which include a remade port of the original alongside a brand-new story mode with new enemies, boss fights and power-up items.[60] A 3D rail-shooter spin-off, Solvalou, was published in 1991.[61] In 1995, two arcade sequels were released - Xevious Arrangement, a remake of the original with two-player co-op,[62] and Xevious 3D/G, a 3D game with 2D gameplay - both of these titles were soon released in 1997 for the PlayStation, compiled into Xevious 3D/G+, alongside the original Xevious and Super Xevious.[63] A final follow-up was released in 2009, Xevious Resurrection, exclusively as part of the compilation title Namco Museum Essentials, which includes two-player simultaneous co-op alongside a number of other features.[64]

Music and books

editIn 1991, a three-part Xevious novel was published, titled Fardraut - the books documented the lore of the Xevious video game series, including its characters, backstory and events. The books would be republished fifteen years later in 2005.[5] A 2002 CGI film adaptation was released in Japan, produced during a collaboration between Namco and Japanese company Groove Corporation.[65]

A Xevious-themed soundtrack album was produced by Haruomi Hosono of Yellow Magic Orchestra in 1984, titled Video Game Music. Compiled with music from other Namco video games, such as Mappy and Pole Position, it is credited as the first video game soundtrack album.[66] Xevious would also spawn the first gameplay recording for a video game[66] and the first television commercial for an arcade game.[67] Music from the game was used during the video game-themed television series Starcade.[67]

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ Akagi, Masumi (October 13, 2006). アーケードTVゲームリスト国内•海外編(1971-2005) [Arcade TV Game List: Domestic • Overseas Edition (1971-2005)] (in Japanese). Japan: Amusement News Agency. pp. 52, 84. ISBN 978-4990251215.

- ^ Kiya, Andrew (October 17, 2021). "Former Namco Pixel Artist Hiroshi 'Mr. Dotman' Ono Has Died". Siliconera. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Xevious guidebook. Wasa. 1984. p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e Xevious instruction manual (FC) (PDF). Namco. 1984. p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Savorelli, Carlo. "Xevious". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on 2017-06-12. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Xevious - Developer Interview Collection". Shmuplations. 2015. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Shigeki Toyama and Namco Arcade Machines". Shmuplations. 2016. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Akagi, Masumi (13 October 2006). ナムコ Namco; Namco America; X (in Japanese) (1st ed.). Amusement News Agency. pp. 53, 126, 166. ISBN 978-4990251215.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "『ナムコミュージアム VOL.2』は、この6タイトル" (in Japanese). Bandai Namco Entertainment. February 1996. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Narusawa, Daisuke (1 March 1991). The Namco Book. JICC Publishing Bureau. ISBN 978-4-7966-0102-3.

- ^ a b c Berkmann, Marcus (February 1987). "Xevious Review". No. 14. Your Sinclair. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Atari unveils advanced video game that is expandable to introductory computer" (Press release). Atari, Inc. 21 May 1984. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography (2003). Family Computer 1983 - 1994. Japan: Otashuppan. ISBN 4872338030.

- ^ Fahey, Mike (14 July 2015). "Ancient Atari 2600 Arcade Port Pops Up, And It's So Bad". Kotaku. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "Once Upon Atari: The Agony and the Ecstasy Video Review". Next Generation. No. 40. Imagine Media. April 1998. p. 20.

- ^ Seff, Micah (21 May 2007). "Xevious and Rush 'n Attack Hit XBLA This Week". IGN. Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Spencer (26 March 2009). "Namco Bandai Backs Virtual Console Arcade In A Big Way". Siliconera. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Ishaan (21 July 2011). "3D Classics: Xevious Flies To The eShop [Update 2]". Siliconera. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ Welsh, Oli (2023-03-16). "Nintendo expands Switch Online library with more Game Boy classics and Kirby". Polygon. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "twitter.com/hamster_corp/status/1446912340486590464". Retrieved 2021-10-12 – via Twitter.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ Parish, Jeremy. "Namco Museum Battle Collection". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2005.

- ^ Aaron, Sean (3 September 2009). "Namco Museum: 50th Anniversary Review (GCN)". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Geddes, Ryan (6 November 2008). "Namco Museum: Virtual Arcade Review". IGN. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Roper, Chris (21 July 2009). "Namco Museum Essentials Review". IGN. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ "Xevious 3D: You've Come a Long Way, Baby". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 94. Ziff Davis. May 1997. p. 109.

- ^ Bates, Jason (1 August 1998). "Revenge of Arcade". IGN. Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Namco Ltd. (2005). Star Fox Assault instruction booklet. Nintendo of America. pp. 7, 29, 34–35.

- ^ Spencer (26 January 2012). "Namco's iPhone Arcade Games Are So Retro You Need To Insert Credits To Play Them". Siliconera. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ a b Alan Weiss, Brett (1998). "Xevious - Review". Allgame. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Xevious (NES) Review". Archived from the original on 15 November 2014.

- ^ "Xevious (Atari 7800) Review". Archived from the original on 14 November 2014.

- ^ a b Millar, Jonathan. "Xevious Review". IGN. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- ^ a b Lacy, Eugene (20 December 1986). "Xevious". Commodore User. No. 40 (January 1987). pp. 26–7.

- ^ a b c Jacques, William (11 September 2004). "Classic NES Series: Xevious - Review". Nintendojo. Archived from the original on 7 January 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Aliens Take a Tumble: Xevious". Computer + Video Games. No. 20 (June 1983). 16 May 1983. p. 31. Archived from the original on 16 September 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Xevious". Vol. 2 (Special ed.). Joystik. October 1983. pp. 40–43. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "EXCITING NEW VIDEO GAME - ギャラガ" (in Japanese). No. 14. Amusement Life. February 1982. p. 21. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ a b MH. "Xevious" (in German). Power Play. p. 57. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ a b Gerstmann, Jeff. "Xevious Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 23 May 2007.

- ^ "Top 100 Video Games". Flux (4). Harris Publications: 32. April 1995.

- ^ a b "Top 100 Games of All Time". Next Generation. No. 21. September 1996. p. 39.

- ^ a b c Reader's Choice of Best Game. Gamest. p. 48. ISBN 9784881994290.

- ^ a b 遠藤昭宏 (June 2003). "ユーゲーが贈るファミコン名作ソフト100選 アクション部門". ユーゲー. No. 7. キルタイムコミュニケーション. pp. 6–12.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (9 May 2008). "Top 10 Atari 7800 Games". IGN. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ ARCADE GAMERS White Paper Vol . 1. Media Pal. 2010. p. 10. ISBN 978-4896101089.

- ^ "Game Machine's Best Hit Games 25 - テーブル型TVゲーム機 (Table Videos)" (PDF). Game Machine (in Japanese). No. 213. Amusement Press. 1 June 1983. p. 29.

- ^ "Top 15 Arcade Games". Video Games. Vol. 1, no. 12. September 1983. p. 82.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Atari Production Numbers Memo". Atari Games. 4 January 2010. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "Japan Platinum Game Chart". The Magic Box. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "ゼビウス". No. 11. Amusement Life. October 1983. pp. 21–22. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Sheff, David (1994) [1993]. "Inside the Mother Brain" (PDF). Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World. Vintage Books. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-307-80074-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-01-02. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

Namco sold 1.5 million copies of a game called "Xevious". A new Namco building was nicknamed the Xevious Building because the game had paid for its construction costs.

- ^ "Fukio "MTJ" Mitsuji - 1988 Developer Interview". BEEP!. 1988. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Sinclair, Brendan (2016-03-17). "Recollections of Rez". GamesIndustry.biz. Archived from the original on 2016-03-22. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- ^ Sharpe, Roger C. (July 15, 1985). "Critic's Corner" (PDF). Play Meter. Vol. 11, no. 13. pp. 25–31.

- ^ Savorelli, Carlo. "Super Xevious: GAMP no Nazo". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "Vs. Super Xevious". Killer List of Video Games. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ "Grobda". Killer List of Video Games. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Savorelli, Carlo. "Xevious: Fardraut Saga (PC-Engine)". Harccore Gaming 101. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Savorelli, Carlo. "Xevious: Fardraut Saga". Harccore Gaming 101. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "Solvalou". Killer List of Video Games. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Savorelli, Carlo. "Xevious Arrangement". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ IGN Staff (11 June 1997). "Xevious 3D/G+". IGN.

- ^ Spencer (28 January 2009). "New Xevious Bundled With PSN Namco Museum". Siliconera. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ^ "Namco Announces Xevious CG Movie". IGN. 8 February 2002. Retrieved 8 February 2002.

- ^ a b The Most Loved Games!! Best 30 Selected By Readers (6th ed.). Gamest. p. 7.

- ^ a b "Xevious". The International Arcade Museum. Retrieved 2012-11-20.

External links

edit- Xevious at the Killer List of Videogames