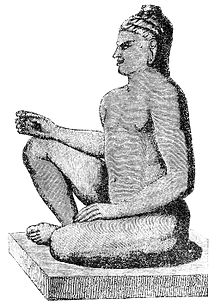

Yasovarman I (Khmer: ព្រះបាទយសោវរ្ម័នទី១) was an Angkorian king who reigned in 889–910 CE. He was called "Leper King".[1]

| Yasovarman I | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of the Khmer Empire | |

| Reign | 889–910 |

| Predecessor | Indravarman I |

| Successor | Harshavarman I |

| Died | 910 |

| Spouse | Sister of Jayavarman IV |

| Issue | Ishanavarman II Harshavarman I |

| Khmer | យសោវរ្ម័នទី១ |

| House | Varman Dynasty |

| Father | Indravarman I |

| Mother | Indradevi |

| Religion | Hinduism |

Early years

editYasovarman was a son of King Indravarman I and his wife Indradevi.[2][3]

Yasovarman was said to be a wrestler. Inscriptions say he was capable of wrestling with elephants. The inscriptions also say he was capable of slaying tigers with his bare hands.

His teacher was the purohit Brahman Vamasiva, part of the Devaraja cult priesthood. Vamasiva's guru, Sivasoma, was connected to the Hindu philosopher Adi Shankara.[4]: 111

After the death of Indravarman, a succession war was fought by his two sons, Yasovarman and his brother, a case of sibling rivalry. It is believed that the war was fought on land and on sea by the Tonlé Sap. In the end Yasovarman prevailed.

Because of his father had sought to deny his accession, according to inscriptions cited by L.P. Briggs, "Yasovarman I ignored his claim to the throne through his father, Indravarman I, or through Jayavarman II, the founder of Angkor dynasty, and built up an elaborate family tree, connecting himself through his mother by matrilineal succession with ancient kings of Funan and Chenla."[5]

Yasovarman I claims to be a descendant of the ruling clans of Sambhupura, Aniditapura, Vyadhapura. This was found on 12 different stone inscriptions located in different parts of the country.[6]

Yasovarman I led a failed invasion of Champa, as documented at Banteay Chmar.[7]: 54

Yasovarman I's achievements

editDuring the first year of his reign, he built about 100 monasteries (ashrams) throughout his kingdom.[4]: 111–112 Each ashram was used as a resting place for the ascetic and the king during his trips. In 893, he began to construct the Indratataka Baray (reservoir) that was started by his father. In the middle of this lake (now dry), he built the temple Lolei.[8]

Yasovarman was one of the great Angkorian kings. His greatest achievement was to move the capital from Hariharalaya to Yashodharapura where it remained there for 600 years.[4]: 103 It was at this new capital where all of the great and famous religious monuments were built, e.g. the Angkor Wat. There were many reasons for the move. The old capital was crowded with temples built by the previous kings. Thus, the decision was religious: In order for a new king to prosper, he must build his own temple and when he died it must become his mausoleum. Second, the new capital was closer to the Siem Reap River and is halfway between the Kulen hills and the Tonlé Sap. By moving the capital closer to the sources of water the king could reap many benefits provided by both rivers.

Yashodharapura was built on a low hill called Bakheng, and connected to Hariharalaya by a causeway. Simultaneously, he started to dig a huge reservoir at his new capital. This new artificial lake, the Yashodharatataka, or the East Baray, with 7.5 by 1.8 km long dykes.[9]: 64–65

The Lolei, Phnom Bakheng, and the East Baray[10] are monuments to this ruler,[11]: 360–362 all located near Cambodia's national treasure, a later construction, Angkor Wat. Phnom Bakheng was one of three hilltop temples created in the Khmer Empire’s Angkor capital region during Yasovarman’s reign, the other two being Phnom Krom and Phnom Bok.[4]: 113

Posthumous name

editYasovarman died in 910 and received the posthumous name of Paramashivaloka. He had leprosy.[12]

Family

editWife of Yasovarman was a sister of Jayavarman IV. She born two sons to Yasovarman – Ishanavarman II and Harshavarman I.[13]

Notes

edit- ^ Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos & the Greater Mekong by Nick Ray, Tim Bewer, Andrew Burke, Thomas Huhti, Siradeth Seng. Page 212. Footscray; Oakland; London: Lonely Planet Publications, 2007.

- ^ Some Aspects of Asian History and Culture by Upendra Thakur. Page 37.

- ^ Saveros, Pou (2002). Nouvelles inscriptions du Cambodge (in French). Vol. Tome II et III. Paris: EFEO. ISBN 2-85539-617-4.

- ^ a b c d Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ^ Briggs, The Ancient Khmer Empire; page 105.

- ^ Briggs, L. P. (1951). The Ancient Khmer Empire. American Philosophical Society, 41(1), page 61.

- ^ Maspero, G., 2002, The Champa Kingdom, Bangkok: White Lotus Co., Ltd., ISBN 9789747534993

- ^ Jessup, p.77; Freeman and Jacques, pp.202 ff.

- ^ Higham, C., 2001, The Civilization of Angkor, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 9781842125847

- ^ Goloubev, Victor. Nouvelles récherches autour de Phnom Bakhen. Bulletin de l'EFEO (Paris), 34 (1934): 576-600.

- ^ Higham, C., 2014, Early Mainland Southeast Asia, Bangkok: River Books Co., Ltd., ISBN 9786167339443

- ^ The Rough Guide to Cambodia by Beverley Palmer and Rough Guides.

- ^ Briggs, Lawrence Palmer. The Ancient Khmer Empire. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 1951.

References

edit- Coedes, George. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. East-West Center Press 1968.

- Higham, Charles. The Civilization of Angkor. University of California Press 2001.

- Briggs, Lawrence Palmer. The Ancient Khmer Empire. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 1951.