This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

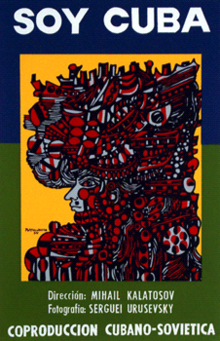

I Am Cuba (Spanish: Soy Cuba; Russian: Я - Куба, Ya – Kuba) is a 1964 film directed by Mikhail Kalatozov at Mosfilm. An international co-production between the Soviet Union and Cuba, it is an anthology film mixing political drama and propaganda.

| I Am Cuba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Mikhail Kalatozov |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Sergey Urusevsky |

| Edited by | Nina Glagoleva |

| Music by | Carlos Fariñas |

| Distributed by | |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 135 minutes / 141 minutes |

| Countries | |

| Languages |

|

The film was almost completely forgotten until it was re-discovered by filmmakers in the United States thirty years later.[1] The acrobatic tracking shots and idiosyncratic mise-en-scène prompted Hollywood directors like Martin Scorsese to begin a campaign to restore the film in the early 1990s.

I Am Cuba is shot in black and white, sometimes using infrared film obtained from the Soviet military[2] to exaggerate contrast (making trees and sugar cane almost white, and skies very dark but still obviously sunny). Most shots are in extreme wide-angle and the camera passes very close to its subjects, whilst still largely avoiding having those subjects ever look directly at the camera.

Plot

editThe movie consists of four distinct short stories about the suffering of the Cuban people and their reactions, varying from passive amazement in the first, to a guerrilla march in the last. Between the stories, a female narrator (credited "The Voice of Cuba") says such things as, "I am Cuba, the Cuba of the casinos, but also of the people."

The first story (centered on the character Maria) shows the destitute Cuban masses contrasted with the splendor in the American-run gambling casinos. Maria lives in a shanty-town on the edge of Havana and hopes to marry her fruit-seller boyfriend, René. He is unaware that she leads an unhappy double-life as "Betty", a bar prostitute at one of the Havana casinos catering to rich Americans. One night, her client asks her if he can see where she lives rather than take her to his own room. She takes him to her small hovel where she reluctantly undresses in front of him. The next morning he tosses her a few dollars and takes her most prized possession, her crucifix necklace. As he is about to leave René walks in and sees his ashamed fiancée. The American callously says, "Goodbye Betty!" as he makes his exit. He is disoriented by the squalor he encounters as he tries to find his way out of the area.

The next story is about a farmer, Pedro, who just raised his best crop of sugar yet. However, his landlord rides up to the farm as he is harvesting his crops and tells him that he has sold the land that Pedro lives on to United Fruit, and Pedro and his family must leave immediately. Pedro asks what about the crops? The landowner says, "you raised them on my land. I'll let you keep the sweat you put into growing them, but that is all," and he rides off. Pedro lies to his children and tells them everything is fine. He gives them all the money he has and tells them to have a fun day in town. After they leave, he sets all of his crops and house on fire. He then dies from the smoke inhalation.

The third story describes the suppression of rebellious students led by a character named Enrique at Havana University (featuring one of the longest camera shots). Enrique is frustrated with the small efforts of the group and wants to do something drastic. He goes off on his own planning on assassinating the chief of police. However, when he gets him in his sights, he sees that the police chief is surrounded by his young children, and Enrique cannot bring himself to pull the trigger. While he is away, his fellow revolutionaries are printing flyers. They are infiltrated by police officers who arrest them. One of the revolutionaries begins throwing flyers out to the crowd below only to be shot by one of the police officers. Later on, Enrique is leading a protest at the university. More police are there to break up the crowd with fire hoses. Enrique is shot after the demonstration becomes a riot. At the end, his body is carried through the streets; he has become a martyr to his cause.

The final part shows Mariano, a typical farmer, who rejects the requests of a revolutionary soldier to join the ongoing war. The soldier appeals to Mariano's desire for a better life for his children, but Mariano only wants to live in peace and insists the soldier leave. Immediately thereafter though, the government's planes begin bombing the area indiscriminately. Mariano's home is destroyed and his son is killed. He then joins the rebels in the Sierra Maestra Mountains, ultimately leading to a triumphal march into Havana to proclaim the revolution.

Cast

edit- Sergio Corrieri as Alberto

- Salvador Wood

- José Gallardo as Pedro

- Raúl García as Enrique

- Luz María Collazo as Maria / Betty

- Jean Bouise as Jim (in Cuban version) (as Jean Bouisse)

- Alberto Morgan as Ángel

- Celia Rodriguez as Gloria (in Cuban version) (as Zilia Rodríguez)

- Fausto Mirabal

Production

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

Shortly after the 1959 Cuban Revolution overthrew the United States-backed dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, the socialist Castro government, isolated by the United States after the latter broke diplomatic and trade relations in 1961, turned to the USSR in many areas, including for film partnerships. The Soviet government, interested in promoting international socialism, and perhaps in need to further familiarize itself with its new ally[citation needed], agreed to collaborate with the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC), and finance a film about the Cuban revolution. Shooting began on February 26, 1963.[3]

The director was given considerable freedom to complete the work,[4] and was given much help from both the Soviet and Cuban governments. Among his inspirations for the project was Sergei Eisenstein's unfinished ¡Que viva México!, another Soviet project about a post-revolutionary Latin American nation.[3] Among Kalatozov's Cuban collaborators on the project were screenwriter Enrique Pineda Barnet and composer Carlos Fariñas.[3]

The film made use of many innovative techniques, such as coating a watertight camera's lens with a special submarine periscope cleaner, so the camera could be submerged and lifted out of the water without any drops on the lens or film. At one point, more than 1,000 Cuban soldiers were moved to a remote location to shoot one scene.

In another scene, the camera follows a flag over a body, held high on a stretcher, along a crowded street.[5] Then it stops and slowly moves upwards for at least four storeys until it is filming the flagged body from above a building. Without stopping, it then starts tracking sideways and enters through a window into a cigar factory, then goes straight towards a rear window where the cigar workers are watching the procession. The camera finally passes through the window and appears to float along over the middle of the street between the buildings. These shots were accomplished by the camera operator having the camera attached to his vest—like an early, crude version of a Steadicam—while also wearing a vest with hooks on the back. An assembly line of technicians would hook and unhook the operator's vest to various pulleys and cables that spanned floors and building roof tops.[citation needed]

Reception

editDespite its dazzling technical and formal achievements receiving excellent support, and the participation of the renowned team of Soviet cinematographers Mikhail Kalatozov and Sergei Urusevsky (winners of the 1958 Cannes Film Festival Palme d'Or for The Cranes are Flying, another virtuosistic art film, and also in the midst of the Cold War), the movie was given a rather cold reaction by audiences. In Havana it was criticized for showing a stereotypical view of Cubans, and in Moscow it was considered naïve, not sufficiently revolutionary, even too sympathetic to the lives of the bourgeois, pre-Castro classes.[citation needed]

The film was shot during a period of relatively uneasy relations between Cuba and the Soviet Union. The recently concluded Cuban Missile Crisis had ended with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev removing its missiles from the island without consulting Cuban leader Fidel Castro, which opened a period of disagreements between the nations over revolutionary strategy.[3]

Cameraman Alexander Calzatti stated that the crew "was so enthusiastic [that] we were infected by it, and we worked very hard"; as a result "very soon after we came back to Russia, more than half of our crew died. I survived because I was very young."[6]

Che Guevara was a fan, writing to Spanish filmmaker Ricardo Muñoz Suay: "It’s the best of the coproductions that we’ve done and an artistically important film. The photography and music are exceptional, and the general tone of the film has a great dignity. It’s a poetic film, often moving, with many inspired moments and few low points. In its images, we can recognize ourselves as a people."[3]

The movie never reached Western countries during its original release, being a communist production in the midst of the Cold War era during the United States embargo against Cuba.

Restoration

editThis article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Until the USSR collapsed in the early 1990s, I Am Cuba was virtually unknown. In 1992, a print of the film was screened at the Telluride Film Festival. The San Francisco International Film Festival screened the film in 1993. Shortly after the festival, three film professionals who had screened I Am Cuba at the San Francisco screening contacted friends at Milestone Films, a small New York film distributor specializing in the release of once-lost and neglected older films. Milestone screened a slightly blurry, unsubtitled VHS tape of the film and then went about acquiring the distribution rights from Mosfilm in Russia.[citation needed] Milestone's release opened at New York's Film Forum in March 1995. For the tenth anniversary of the film release, Milestone debuted a new 35 mm restoration of I Am Cuba without the Russian overdubbing in September 2005. Milestone released an Ultimate Edition DVD boxset at the time as well, with a video appreciation from Scorsese.

On 19 March 2018, Milestone posted a trailer for their new 4K restoration of the film.[7] It became available later that year on Milestone films' Vimeo powered streaming service, with original Spanish audio but at 1080p HD.

On 9 March 2020, Mosfilm publicly released the entire film in 4K with hardcoded Russian overdubbing on their YouTube channel.[8]

Sometime after April 2021, the film was removed from Milestone films' streaming catalog on Vimeo because they sold the film's US distribution license, assumably back to Mosfilm. Milestone never released the film in 4K but gave refunds to upset customers.[citation needed]

On 29 October 2021, Mosfilm released the film on their English-language YouTube channel. From an archival perspective, it is inferior[fact or opinion?] to Mosfilm's previous 4K release due to its hardcoded English subtitles, watermarking, Russian overdubbing, and 16:9 pillarboxing.[citation needed]

The Criterion Collection released a 4K restoration of I Am Cuba on Blu-ray and 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray, with the film's original Spanish audio, in April 2024.[9][10]

Documentary

editIn 2005, a documentary about the making of I Am Cuba was released called Soy Cuba: O Mamute Siberiano or I Am Cuba: the Siberian Mammoth, directed by the Brazilian Vicente Ferraz. The documentary looks at the history of the making of the film, explains some of the technical feats of the film, and features interviews with many of the people who worked on it.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ The New Cult Canon: I am Cuba Archived 10 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The A.V. Club, 1 May 2008.

- ^ 2005 Brazilian documentary The Siberian Mammoth

- ^ a b c d e García Borrero, Juan Antonio. "I Am Cuba: The Filmmakers Who Came In from the Cold". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ "The Astonishing Images of I Am Cuba – The American Society of Cinematographers". ascmag.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "BBC – Stoke and Staffordshire Films – I Am Cuba (Soy Cuba) review". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "The Astonishing Images of I Am Cuba", George E. Turner 2019-05-17, American Cinematographer

- ^ "I Am Cuba". Milestone Films. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ^ I AM CUBA (4K, drama, directed by Mikhail Kalatozov, 1964). Mosfilm on YouTube. 9 March 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ "I Am Cuba". Criterion.com. The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ Martin, Peter (16 January 2024). "Criterion in April 2024: La Haine, I Am Cuba, Picnic at Hanging Rock in 4K". Screen Anarchy. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

External links

edit- I Am Cuba at IMDb

- I Am Cuba at Rotten Tomatoes

- I Am Cuba at AllMovie

- Soy Cuba, O Mamute Siberiano at IMDb

- From Russia with Love, an article by Richard Gott from The Guardian November 2005

- "The 34 best political movies ever made", Ann Hornaday, The Washington Post 23 January 2020), ranked #28