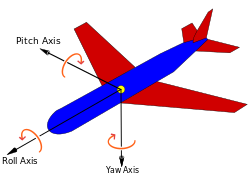

An aircraft in flight is free to rotate in three dimensions: yaw, nose left or right about an axis running up and down; pitch, nose up or down about an axis running from wing to wing; and roll, rotation about an axis running from nose to tail. The axes are alternatively designated as vertical, lateral (or transverse), and longitudinal respectively. These axes move with the vehicle and rotate relative to the Earth along with the craft. These definitions were analogously applied to spacecraft when the first crewed spacecraft were designed in the late 1950s.

These rotations are produced by torques (or moments) about the principal axes. On an aircraft, these are intentionally produced by means of moving control surfaces, which vary the distribution of the net aerodynamic force about the vehicle's center of gravity. Elevators (moving flaps on the horizontal tail) produce pitch, a rudder on the vertical tail produces yaw, and ailerons (flaps on the wings that move in opposing directions) produce roll. On a spacecraft, the movements are usually produced by a reaction control system consisting of small rocket thrusters used to apply asymmetrical thrust on the vehicle.

Principal axes

edit-

Yaw

-

Pitch

-

Roll

- Normal axis, or yaw axis — an axis drawn from top to bottom, and perpendicular to the other two axes, parallel to the fuselage or frame station.

- Transverse axis, lateral axis, or pitch axis — an axis running from the pilot's left to right in piloted aircraft, and parallel to the wings of a winged aircraft, parallel to the buttock line.

- Longitudinal axis, or roll axis — an axis drawn through the body of the vehicle from tail to nose in the normal direction of flight, or the direction the pilot faces, similar to a ship's waterline.

Normally, these axes are represented by the letters X, Y and Z in order to compare them with some reference frame, usually named x, y, z. Normally, this is made in such a way that the X is used for the longitudinal axis, but there are other possibilities to do it.

Vertical axis (yaw)

editThe yaw axis has its origin at the center of gravity and is directed towards the bottom of the aircraft, perpendicular to the wings and to the fuselage reference line. Motion about this axis is called yaw. A positive yawing motion moves the nose of the aircraft to the right.[1][2] The rudder is the primary control of yaw.[3]

The term yaw was originally applied in sailing, and referred to the motion of an unsteady ship rotating about its vertical axis. Its etymology is uncertain.[4]

Lateral axis (pitch)

editThe pitch axis (also called transverse or lateral axis),[5] passes through an aircraft from wingtip to wingtip. Rotation about this axis is called pitch. Pitch changes the vertical direction that the aircraft's nose is pointing (a positive pitching motion raises the nose of the aircraft and lowers the tail). The elevators are the primary control surfaces for pitch.[3]

Longitudinal axis (roll)

editThe roll axis (or longitudinal axis[5]) has its origin at the center of gravity and is directed forward, parallel to the fuselage reference line. Motion about this axis is called roll. An angular displacement about this axis is called bank.[3] A positive rolling motion lifts the left wing and lowers the right wing. The pilot rolls by increasing the lift on one wing and decreasing it on the other. This changes the bank angle.[6] The ailerons are the primary control of bank. The rudder also has a secondary effect on bank.[7]

Reference planes

editThe principal axes of rotation imply three reference planes, each perpendicular to an axis:

- Normal plane, or yaw plane

- Transverse plane, lateral plane, or pitch plane

- Longitudinal plane, or roll plane

The three planes define the aircraft's center of gravity.

Relationship with other systems of axes

editThese axes are related to the principal axes of inertia, but are not the same. They are geometrical symmetry axes, regardless of the mass distribution of the aircraft.[citation needed]

In aeronautical and aerospace engineering intrinsic rotations around these axes are often called Euler angles, but this conflicts with existing usage elsewhere. The calculus behind them is similar to the Frenet–Serret formulas. Performing a rotation in an intrinsic reference frame is equivalent to right-multiplying its characteristic matrix (the matrix that has the vectors of the reference frame as columns) by the matrix of the rotation.[citation needed]

History

editThe first aircraft to demonstrate active control about all three axes was the Wright brothers' 1902 glider.[8]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Yaw axis". Answers.com. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ^ "Specialty Definition: YAW AXIS". Archived from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ^ a b c Clancy, L.J. (1975) Aerodynamics Pitman Publishing Limited, London ISBN 0-273-01120-0, Section 16.6

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ a b "MISB Standard 0601" (PDF). Motion Imagery Standards Board (MISB). Retrieved 1 May 2015. Also at File:MISB Standard 0601.pdf.

- ^ Wragg, David W. (1973). A Dictionary of Aviation (first ed.). Osprey. p. 224. ISBN 9780850451634.

- ^ FAA (2004). Airplane Flying Handbook. Washington D.C.:U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, ch 4, p 2, FAA-8083-3A.

- ^ "Aircraft rotations". Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

External links

edit- Pitch, Roll, Yaw

- Yaw Axis Control as a Means of Improving V/STOL Aircraft Performance.

- 3D fast walking simulation of biped robot by yaw axis moment compensation

- Flight control system for a hybrid aircraft in the yaw axis

- Motion Imagery Standards Board (MISB) Archived 2022-08-23 at the Wayback Machine