This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Korean. (May 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The Yeosu-Suncheon rebellion, also known as the Yeo-Sun incident (Yeo-Sun an abbreviation of Yeosu and Suncheon), was a rebellion that began in October 1948 and mostly ended by November of the same year. However, pockets of resistance lasted through to 1957, almost 10 years later.

| Yeosu–Suncheon rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the division of Korea | |||||||

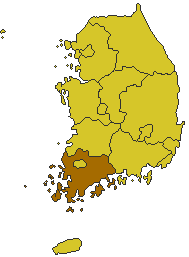

Map of South Korea with South Jeolla highlighted | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Local supporters |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,000–3,000 | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,976–3,392 total dead, South Korea's Ministry of National Defense and Jeollanam-do Provincial Government source claim 12,000 total dead.[1] | |||||||

It is often called a "rebellion incident", but it is used as a case of "Yeosu and Suncheon incident" or "Yeosu, Suncheon 10.19 incident" since 1995 because the residents of the area may have mistaken it as the main object of the uprising.[2]

The rebellion took place in the cities of Yeosu and Suncheon and various surrounding towns in the South Jeolla province of South Korea. Rising anti-government sentiment towards the Syngman Rhee regime ignited in rebellion as 2,000 left-leaning soldiers based in the Yeo-Sun area raised arms in opposition to the Rhee government's handling of the Jeju Uprising, which had occurred just months earlier in April.

Park Chung-hee, who would later become a president of South Korea during military dictatorship era, participated in the rebellion, although he was allegedly given leniency in exchange for aiding in the hunt for others involved in the rebellion.[3]

Background and lead-up

editPolitical situation in Korea

editAfter Imperial Japan surrendered to Allied forces on 15 August 1945, the 35-year Japanese occupation of Korea finally came to an end. Korea was subsequently divided at the 38th parallel north, with the Soviet Union accepting Japanese surrender north of the line and the United States south of the line.

In August 1945, the newly formed Committee for the Preparation of Korean Independence (CPKI) organized democratic people's committees throughout the country to coordinate the transition to independence. By the end of August, over 140 democratic People's Committees had been established throughout the country. On September 6, the CPKI met in Seoul and the People's Republic of Korea was established as the provisional government of Korea. The PRK took over security and administrative control of Seoul and other areas and oversaw the release of political prisoners and the peaceful evacuation of Japanese forces.[4]

In September 1945, Lt. General John R. Hodge landed on the Korean peninsula. Hodge refused to acknowledge the authority of the People's Committees and the PRK. He established a US military presence (USAMGIK) to control the southern half of Korea, which included Jeju Island and the areas in South Jeolla around Yeosu and Suncheon. Hodge brought Japanese soldiers back to Seoul to staff the USAMGIK - a decision which was abandoned almost immediately due to public uproar. Locals were outraged at the military presence that denied their right to political independence. Unable to use Japanese forces, Hodge staffed 80% of USAMGIK forces with former members of the colonial police. Over the next year, USAMGIK forces violently ousted the People's Committees in the countryside.[5]

In December 1945 U.S. representatives met with those from the Soviet Union and United Kingdom to work out joint trusteeship. Due to lack of consensus, however, the U.S. took the “Korean question” to the United Nations for further deliberation. On November 14, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed UN Resolution 112, calling for a general election on May 10, 1948, under UNTCOK supervision.

Fearing it would lose influence over the northern half of Korea if it complied, the Soviet Union rejected the UN resolution and denied the UNTCOK access to northern Korea. The UNTCOK nevertheless went through with the elections, albeit in the southern half of the country only. The Soviet Union responded to these elections in the south with an election of its own in the north on August 25, 1948.

Suppression of the Jeju Uprising

editThe Jeju uprising was an insurgency on the Korean province of Jeju Island which was followed by an anticommunist suppression campaign that lasted from April 3, 1948, until May 1949. The main cause for the protests were the elections scheduled for May 10, 1948, designed by the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) to create a new government for all of Korea. The elections, however, were only planned for the south of the country, the half of the peninsula under UNTCOK control. Fearing the elections would further reinforce established division, guerrilla fighters of the Workers' Party of South Korea (WPSK) reacted by fighting local police and rightist youth groups stationed on Jeju Island.

Though atrocities were committed by both sides, the methods used by the South Korean government to suppress the rebels were especially cruel. On one occasion, American soldiers discovered the bodies of 97 people including children, killed by government forces. On another, American soldiers caught government police forces carrying out an execution of 76 villagers, including women and children.

In the end, between 14,000 and 30,000 people died as a result of the rebellion, or up to 10% of the island’s population. Some 40,000 others fled to Japan to escape the fighting. In the decades after the uprising, memory of the event was suppressed by the government through censorship and repression. In 2006, almost 60 years after the rebellion, the Korean government apologized for its role in the killings. The government also promised reparations but as of 2017, nothing had been done to this end.

Rebellion

editThe rebellion took place in Yeosu, Suncheon, and various surrounding towns in the South Jeolla province in October–November 1948. The rebellion was led by 2,000 left-leaning soldiers based in the Yeo-Sun area who opposed the Syngman Rhee regime and his government's handling of the Jeju Uprising, which occurred in April.

The rebelling soldiers seized weapon caches in the area, taking control of Suncheon. Civilians in support of the rebellion paraded through the streets waving red flags. Police officers as well as public officials and landlords attempting to quell the violence were captured and executed. As the rebellion spread, the number of soldiers participating has been estimated to have reached between 2,000 and 3,000 men. The soldiers captured and massacred police and pro-government vigilantes as well as right-leaning families and Christian youth groups[dubious – discuss].[6]

After a week, the South Korean Army had suppressed the majority of resistance,[7] in the process killing anywhere from 439 to 2,000 civilians.[8] The South Korean Army was led by US commanders, with military advisors attached to each South Korean Army unit. US aircraft were used to transport troops to suppress the rebellion.[7]

Carl Mydans, at the time the Time-Life Tokyo bureau chief, recorded the Yeosu-Suncheon incident in 1948.

October

editThe Yeosu-Suncheon Rebellion (or Incident) began when members of a South Korean military regiment in Yeosu refused to transfer to Jeju Island; they were sympathetic to the leftists and opposed the Rhee government and the decisive U.S. influence in South Korea.

On the night of October 19, 40 soldiers (who were members of the Workers' Party of South Korea, a leftist party) of the 14th regiment of Yeosu army took hold of the arsenal in the absence of the regimental commander and vice regimental commander. Ji Hang-soo, chief of the 14th regiment personnel section, asked more than 2000 soldiers to gather at their drill ground and gave an inflammatory speech. Most of the soldiers who were sympathetic to the DPRK cheered to Ji's speech, and those were against Ji were executed on the spot[citation needed]. Those who stood with Ji formed a rebel army, who proceeded to get on different cars to seize the police station of Yeosu and Yeosu Town Hall, killing about 100 police officers, about 500 civilians who supported the Rhee government, as well as some right wing politicians and party members under Rhee's regime.

By October 20, the insurgent forces took hold of the entirety of Yeosu and joined the 2nd Company of the 14th Regiment who were stationed in Suncheon County. In the afternoon, Suncheon got occupied by the rebel army. One company belonging to the 4th Regiment of Gwangju army was immediately dispatched to suppress the rebellion, but its commander got killed, and his company was merged into the rebel army.

On October 21, Syngman Rhee declared martial law in the Yeosu-Suncheon region, and sent 10 battalions in an attempt to contain the situation. The rebel army then began to attack surrounding areas such as Gwangyang, Gokseong, Boseong and Gurye. On October 22, the rebel army was gradually shifting to Jirisan.

On the morning of October 23, Rhee's troops began to attack Suncheon, which was occupied by the rebels. As a result, main forces of the rebel army retreated to Yeosu and the mountainous regions in the north. By 11 am, Rhee's troops entered the urban area of Suncheon, where there were only defenseless students and civilians left, and proceeded to pursue the insurgent forces in Yeosu.

On October 24, pursuing troops of Rhee's army were ambushed by the rebel army. More than 270 soldiers of the troops died, and their commander in chief was also severely injured. Meanwhile, main forces of the rebel army began to transfer to Jirisan in the north.

On October 25, Rhee's troops began to attack Yeosu, where they were resisted by more than 200 soldiers of the rebel army, as well as 1000 students and civilians.

After two days of street battles, the area was fully suppressed by October 27. A wide-range search for alleged accomplices of the insurgent forces was ordered by Rhee as revenge. Those who were suspected of being accomplices of the rebel forces were taken into an elementary school and executed, with bodies of thousands of innocent civilians piling up inside the school.

November – containment and suppression

editThe uprising was largely contained by early November, but scattered guerrilla activity continued well into 1957. Even after Yeosu and Suncheon was fully suppressed, Rhee's army still went on to search for accomplices of the rebel forces in the surrounding areas and executed many civilians living around Yeosu and Suncheon, claiming that there were still rebel forces left in both areas.

The United States Involvement

editAs in the case of the United States' involvement in the Jeju Uprising the US played a role in the Yeosu-Suncheon rebellion as well, both militarily and materially. The background of US participation was due to its military presence in South Korea at that time. US military advisors were sent to Yeosu to assist the South Korean forces. The advisors' task consisted of the "Suppression and extermination of subversive element in South Korea." Furthermore the US appointed Song Ho Sung (송호성) commander of the punitive forces headquarters. James H. Hausman was dispatched as personal advisor in the role of a military assistant to Song Ho Sung. Though the US did not send ground forces during this uprising, however the military advisors who were dispatched to each unit of the government forces exercised control and command over military operations owing to their military authority.[9]

After the rebellion: fatalities and impact of the incident

editDuring the Yeosu-Suncheon Rebellion, between 2,976 and 3,392 people died (depending on the sources), some 82 people went missing, between 1,407 and 2,056 people were injured, 152 soldiers were executed by special court martial, and 5,242 homes were destroyed.[citation needed]

Rhee learned from this rebellion that the Korean army had been infiltrated by members of the Workers Party of South Korea, and soon started a full-scale purge of communists: members of the Workers Party of South Korea and soldiers who came from the Korean Liberation Army were all expelled from the South Korean army.

Moreover, these acknowledgements led Rhee to oppress officers who did not favor him as the president. As a result, 18 officers and 1,693 enlisted in 1948; and 224 officers and 2,440 enlisted in 1949 were terminated from their military service.[10]

In the meantime, Park Chung-hee, who would later become the president of Korea, was arrested and was sentenced to life at first, but it was alleged that he was punished leniently in exchange for agreeing to hunt down people involved in the rebellion through Paik Sun-yup. Moreover, because of the rebellion, Rhee enacted the National Security Law on December 1, 1948.

After the rebellion, residents in the western region of the country were forced to remain silent about the incident, which was also the case with the Jeju uprising.

The matter was recently reviewed by the South Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which found that government forces killed between 439 and 2,000 area civilians.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "국가폭력 단죄하지 않으면 문명 국가로 갈 수 없다"

- ^ "Yeosu and Suncheon incident". naver dictionary.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (1981). The Origins of the Korean War, Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945–1947. Princeton University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-0691101132.

- ^ Hart-Landsberg, Martin (1998). Korea: Division, Reunification, and U.S. Foreign Policy. p. 65.

- ^ Robinson, Michael (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. University of Hawai-i Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0-8248-3080-9.

- ^ Stueck, William (2004). The Korean War in World History. University Press of Kentucky. p. 39. ISBN 978-0813123066.

- ^ a b Hart-Landsberg, Martin (1998). Korea: Division, Reunification, & U.S. Foreign Policy. Monthly Review Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0853459279.

- ^ "439 civilians confirmed dead in Yeosu-Suncheon Uprising of 1948 New report by the Truth Commission places blame on Syngman Rhee and the Defense Ministry, advises government apology". The Hankyoreh. January 8, 2009.

- ^ 김득중 (2009). 빨갱이의 탄생, 도서출판 선인, p. 274~281. ISBN 9788959331628.

- ^ 한국사연대기. "동포의 학살을 거부한다".