Yo Soy 132, commonly stylized as #YoSoy132, was a protest movement composed of Mexican university students from both private and public universities, residents of Mexico, claiming supporters from about 50 cities around the world.[2] It began as opposition to the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) candidate Enrique Peña Nieto and the Mexican media's allegedly biased coverage of the 2012 general election.[3] The name Yo Soy 132, Spanish for "I Am 132", originated in an expression of solidarity with the original 131 protest's initiators. The phrase drew inspiration from the Occupy movement and the Spanish 15-M movement.[4][5][6] The protest movement was known worldwide as the "Mexican spring"[7][8] (an allusion to the Arab Spring) after claims made by its first spokespersons,[9] and called the "Mexican occupy movement" in the international press.[10]

| Yo Soy 132 | |

|---|---|

| Part of the 2012 Mexican general election, Impact of the Arab Spring | |

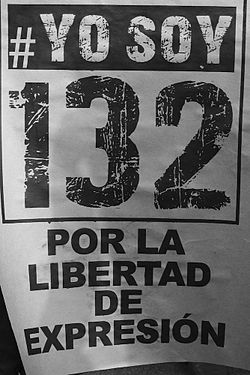

Poster stating #YoSoy132 against EPN: it's not hate nor intolerance against his name, but rather being full of indignation as to what he represents | |

| Date | 15 May 2012 –2013[1] |

| Location | Mexico |

| Caused by | |

| Goals |

|

| Methods | |

| Resulted in |

|

| www www @Soy132mx @global132 | |

Origins

editOn May 11, 2012, then Institutional Revolutionary Party Mexican Presidential Candidate Enrique Peña Nieto visited the Ibero-American University to present his political platform to the students as part of the Buen Ciudadano Ibero (good Ibero citizen)[11] forum. At the end of his discussion, he was asked by a group of students a question regarding the 2006 civil unrest in San Salvador Atenco, in which then-governor of the State of Mexico Peña Nieto called in state police to break up a protest by local residents, which led to several protestors being violently beaten, raped, and others killed (including a child).[12] Peña responded that it was a decisive action that he personally enacted, to re-establish order and peace within the legitimate rights of the State of Mexico to use public force, and that it was found valid by the National Supreme Court.[13] His response was met with applause by his supporters and slogans against his campaign from students who disliked his statement.[14]

Video of the event was recorded by various students and uploaded onto social media, but major Mexican television channels and national newspapers reported that the protest was not by students of the university.[15] This angered many of the Ibero-American University students, prompting 131 of them to publish a video on YouTube identifying themselves by their University ID card.[16] The video went viral, and protests spread across various campuses. People showed their support of the 131 students' message by stating, mainly on Twitter, that they were the 132nd student—"I am 132"— thus giving birth to the Yo Soy 132 movement.

Protests

editSince the beginning of the movement, protest tactics included silent marches, concerts, encouraging political participation in elections, and marching without being on the street and disrupting traffic.[citation needed] Rallies and marches happened in the capital, Mexico City, and also in 12 of the 32 states of the Mexican Republic.[17]

Outside of Mexico, various individuals, mostly Mexican students benefited by government grants for studying abroad, created their own messages of solidarity from the country they were studying.[18]

The success of the movement in unifying thousands of students prompted political analysts to consider whether the movement would cause trouble for the next government in the election results.[19] This was not to be the case, although the fairness of the elections was criticized.[20]

Goals

editOn June 5, 2012, students gathered at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), the country's largest public university, and agreed that the movement should aspire to go beyond the general election and become a national force.[21]

General principles

editOn August 10, 2012, YoSoy132 International group published a translation of the General Principles.[22][23][24]

The movement claimed as a success of their demands that the second Mexican presidential debate was broadcast nationwide; however, the broadcast was done by Televisa and TV Azteca, both companies previously labeled by the movement as unreliable and untrustable sources of information. It also proposed a third debate organized by members of the Yo Soy 132 movement that was held without the presence of Enrique Peña Nieto, who rejected the invitation and said it lacked conditions of impartiality. This third debate was accessible only to the privileged society with access to broadband internet, something that wasn't common in 2012 in Mexico, which led to criticism.[citation needed]

Public opinion

editSupport

editYo Soy 132 was compared by their first spokespersons to the Arab Spring movement that occurred in the Arab world, as well as the Occupy movement.[25]

This is because all three movements rely on grassroots support and have used social media as a way to communicate and organize, as well as using civil resistance.[original research?]

The Occupy Wall Street movement acknowledged these similarities by writing a post on their website expressing their solidarity with Yo Soy 132.[26]

The movement also promotes a leaderless structure, in which no one person is the leader, as well as having multiple demands.[27]

Opposition

editOn June 11, 2012, four persons who named themselves generación mx, through a YouTube video claimed they were allegedly part of Yo Soy 132 and announced their supposed departure, claiming that they perceived that the movement favored the leftist candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador.[28] They claimed to have the same goals as the Yo Soy 132 movement of democratization of the media, political reform, environmental protection, and calling politicians' attention to the agenda of Mexican youth.[28]

It was later uncovered by social network activists that the generacion mx members were directly linked to Peña Nieto's political party, the PRI, the one Yo Soy 132 was campaigning against.[29][30]

A spokesperson of GenerationMX denied ties with the PRI party and his current employer COPARMEX.[31]

The movement has also been opposed on social media by so-called Peñabots - automated accounts used for propaganda purposes.[32][33]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Qué ocurrió con los integrantes del movimiento #yosoy132". Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ "#YoSoy132 presume contar con 52 asambleas internacionales". Proceso.com.mx. August 1, 2012. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ "Youth protest former Mexican ruling party's rise". Buenos Aires Herald. Editorial Amfin S.A. Archived from the original on May 21, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ Quesada, Juan Diego (May 27, 2012). "Que nadie cierre las libretas: Del 15-M a Yo Soy 132 solo hay nueve mil kilómetros". Animal Político. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Sotillos, Alberto (June 13, 2012). "#YoSoy132: el 15M llega a México" (in Spanish). Diario Progresista. Archived from the original on June 27, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ "#YoSoy132: Mexican Elections, Media, and Immigration". The Huffington Post. AOL. June 7, 2012. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Kilkenny, Allison (May 29, 2012). "Student Movement Dubbed the 'Mexican Spring'". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Catherine E. Shoichet and Mauricio Torres (May 25, 2012). "Social media fuel Mexican youth protests". CNN. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "Social media fuel Mexican youth protests - CNN". CNN. Turner Broadcasting System. May 24, 2012. Archived from the original on June 12, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ Hernandez, Rigoberto (June 7, 2012). ""Mexican Spring" Comes to San Francisco". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Corporation. Archived from the original on June 11, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ "¿Y qué dijo Peña Nieto en la Ibero?". CNN Expansión. May 11, 2012. Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ Zapata, Belén (June 4, 2012). "Atenco, el tema que 'encendió' a la Ibero y originó #YoSoy132". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "Atenco, el tema que 'encendió' a la Ibero y originó #YoSoy132". Expansión (in Mexican Spanish). Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ Zapata, Belén. "La visita de Peña Nieto, motivo de abucheos de estudiantes en la Ibero". Mexico.cnn.com (in Spanish). CNN México. Archived from the original on June 2, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

Al término de su discurso, los estudiantes permanecieron aglomerados a las afueras del auditorio en espera de la salida del abanderado del PRI y a gritarle "¡Fuera! ¡Fuera!" y "¡Asesino!"

- ^ Organización Editorial Mexicana (May 11, 2012). "Intentan boicotear en la Ibero a Peña Nieto" (in Spanish). El Sol de México. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ "131 Alumnos de la Ibero responden". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 4, 2017. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ "Videos de Solidaridad Nacional". Yosoy132nacional.wikispaces.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ "Videos de solidaridad Internacional". Yosoy132nacional.wikispaces.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Graham, Dave (June 19, 2012). "Mexican students won't protest if frontrunner wins vote fairly". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- ^ "Irregularities reveal Mexico's election far from fair". The Guardian. July 9, 2012. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ ""Yo soy 132": Declaratoria y pliego petitorio" (in Spanish). Animal Político. Archived from the original on June 13, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ "Conferencia de Prensa de la Asamblea General 18 de junio de 2012". Yosoy132media.org. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ "Conferencia de prensa de la asamblea general". Ustream.tv. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ "Principios Generales del Movimiento". Yosoy132media.org. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ Kilkenny, Allison (May 29, 2012). "Student Movement Dubbed the 'Mexican Spring'". The Nation. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ "#TodosSomos132:Solidarity with the Mexican Spring". May 25, 2013. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Look, Carolyn (December 26, 2012). "YoSoy132 and Contemporary Uprisings: What are Social Movements doing wrong". Archived from the original on November 7, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ a b Ascensión, Arturo (June 11, 2012). "Jóvenes rompen con #YoSoy132 y forman el grupo GeneraciónMX". CNNMéxico. Turner Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on June 12, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ Lucas, Nicolás (June 12, 2012). "Denuncian que #GeneracionMx es cercano al PRI y Coparmex". El Financiero (in Spanish). El Financiero Comercial S.A. de C.V. Archived from the original on June 15, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Milenio TV. Grupo Multimedios (June 12, 2012). "Integrante de #GeneraciónMX también aparece en video de apoyo a EPN" (in Spanish). YouTube. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Rea, Daniela (June 12, 2012). "E-mail Presentan en solitario a #GeneraciónMX" (in Spanish). Terra News. Archived from the original on June 16, 2012. Retrieved June 22, 2012.

- ^ Mundo, Alberto Nájar BBC; México, Ciudad de (March 17, 2015). "¿Cuánto poder tienen los Peñabots, los tuiteros que combaten la crítica en México?". BBC News Mundo. Archived from the original on March 22, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ^ Finley, Klint. "Pro-Government Twitter Bots Try to Hush Mexican Activists". Wired. Archived from the original on March 15, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

External links

edit- Yo Soy 132 official website (in Spanish)

- Yo Soy 132 international website (in Spanish)

- 131 students original video on YouTube