Zero for Conduct (French: Zéro de conduite) is a 1933 French featurette directed by Jean Vigo. It was first shown on 7 April 1933 and was subsequently banned in France until November 1945.[2]

| Zéro de conduite | |

|---|---|

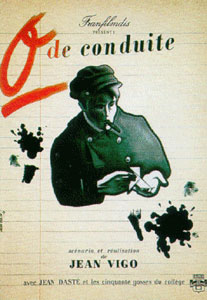

1946 re-release poster by Jean Colin[1] | |

| Directed by | Jean Vigo |

| Written by | Jean Vigo |

| Produced by | Jean Vigo |

| Starring | Jean Dasté |

| Cinematography | Boris Kaufman |

| Edited by | Jean Vigo |

| Music by | Maurice Jaubert |

Production company | Argui-Films |

| Distributed by | Gaumont Film Company Comptoir Français de Distribution de Films Franfilmdis |

Release date |

|

Running time | 48 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Budget | ₣200,000 |

The film draws extensively on Vigo's boarding school experiences to depict a repressive and bureaucratised educational establishment in which surreal acts of rebellion occur, reflecting Vigo's anarchist view of childhood. The title refers to a mark the boys would get which prevented them from going out on Sundays.

Though the film was not an immediate success with audiences, it has proven to be enduringly influential. François Truffaut paid homage to Zero for Conduct in his film The 400 Blows (1959). The anarchic classroom and recess scenes in Truffaut's film borrow from Vigo's film, as does a classic scene in which a mischievous group of schoolboys are led through the streets by one of their schoolmasters. Director Lindsay Anderson has acknowledged that his own film if.... was inspired by Zero for Conduct.

Plot

editFour rebellious young boys at a repressive French boarding school plot and execute a revolt against their teachers and take over the school.[3]

Cast

edit- Gérard de Bédarieux – Tabard

- Louis Lefebvre – Caussat

- Gilbert Pruchon – Colin

- Coco Golstein – Bruel

- Jean Dasté – Surveillant Huguet

- Robert le Flon – Surveillant Pète-Sec

- Du Verron – Surveillant-Général Bec-de-Gaz (as du Verron)

- Delphin – Principal du Collège

- Léon Larive – Professeur (as Larive)

- Madame Émile – Mère Haricot (as Mme. Emile)

- Louis de Gonzague – Préfet (as Louis de Gonzague-Frick)

- Raphaël Diligent – Pompier (as Rafa Diligent)

Production

editIn late 1932, Vigo and his wife Lydou Vigo were both in poor health and Vigo was at a low point in his career. He then met and befriended Jacques-Louis Nounez, a rich businessman who was interested in making films. Vigo discussed the idea of a film about his childhood experiences at a Millau boarding school and Nounez agreed to finance it.[3]

Zero for Conduct was shot from December 1932 until January 1933 with a budget of 200,000 francs. Vigo used mostly non-professional actors and sometimes people that he found on the street. The four main characters are all based on real people that Vigo had known in his youth. Caussat and Bruel were based on friends from Millau, Colin was based on a friend he had known in Chartes and Tabard was based on Vigo himself. The teachers depicted in the film were based on the guards at La Petite Roquette juvenile prison where Vigo's father Miguel Almereyda had once been an inmate. The film's soundtrack was of poor quality due to budgetary constraints but Vigo's use of poetic, rhythmic dialogue has been said to make it much easier to understand what characters are saying.[3] At one point in the film, Tabard tells his teachers "shit on you!", which was once a famous headline in a French newspaper that Vigo's father had directed at all world governments. Vigo's poor health became worse during the film's production but he was able to complete the editing.[4]

Reception

editThe film was first screened on April 7, 1933, in Paris. The premiere shocked many audience members who hissed and booed Vigo. Other audience members, most notably Jacques Prevert, loudly clapped.[4]

French film critics were strongly divided about the film. Some called it "simply ridiculous" and compared it to "lavatory flushing" while others praised its "fiery daring" and called Vigo "the Céline of the cinema."[4] The film's most vocal critics included a French Catholic journal which called it a scatological work by "an obsessed maniac." Zero for Conduct was quickly banned in France, with some believing that the French Ministry of the Interior considered it a threat capable of "creating disturbances and hindering the maintenance of order."[4]

Rediscovery

editLike all of Vigo's work, Zero for Conduct first began to be rediscovered in about 1945 when a revival screening of his films was organized. Since then, its reputation has grown and it has influenced such films as François Truffaut's The 400 Blows (1959) and Lindsay Anderson's if.... (1968).[4] Truffaut praised the film and said that "in one sense Zero de Conduite represents something more rare than L'Atalante because the masterpieces consecrated to childhood in literature or cinema can be counted on the fingers of one hand. They move us doubly since the esthetic emotion is compounded by a biographical, personal and intimate emotion ... They bring us back to our short pants, to school, to the blackboard, to vacations, to our beginnings in life."[5]

Style and themes

editVigo's biographer Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes has discussed Vigo's "extreme sensitivity to anything concerning a child's vulnerability in the adult world" and his "respect for children and their feelings."[4]

Gomes also compared the boarding school in the film to a microcosm of the world, stating that "the division to the children and adults inside the school corresponds to the division of society into classes outside: a strong minority imposing its will on a weak majority."[4]

Awards

editThe 2011 Parajanov-Vartanov Institute Award posthumously honoured Jean Vigo's Zero for Conduct[6] and was presented to his daughter and French film critic Luce Vigo by the actor Jon Voight.[7] Martin Scorsese wrote a letter for the occasion, with praise for Vigo, Sergei Parajanov and Mikhail Vartanov, all of whom struggled with heavy censorship.[7]

References

edit- ^ "Zero de conduite Original R1946 French Grande Movie Poster". Posteritati. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Temple 2011, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Wakeman 1987, p. 1139.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wakeman 1987, p. 1140.

- ^ Insdorf 1978, p. 145.

- ^ Nicholas Rapold (7 April 2011). "Son of Anarchy, Father of a Critic: A Tribute to Jean Vigo at UCLA". LA Weekly.

- ^ a b "Jean Vigo". Parajanov-Vartanov Institute. 9 February 2017.

Bibliography

edit- "Zéro de Conduite", L'Avant-Scène du Cinéma (21): 1–28, 1962 (includes complete script)

- Gomes, P. E. Salles (1998). Jean Vigo. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1957. ISBN 0-571-19610-1.

- Insdorf, Annette (1978). François Truffaut. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47808-1.

- Le Cain, Maximilian. "Jean Vigo". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- Temple, Michael (2011). Jean Vigo. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719056338.

- Wakeman, John (1987). World Film Directors, Volume 1, 1890–1945. New York: The H. W. Wilson Company, 1987. ISBN 978-0-82420-757-1.

- Weir, David (2014). Jean Vigo and the Anarchist Eye. Atlanta: On Our Own Authority!. ISBN 978-0990641810.

External links

edit- Zero for Conduct at IMDb

- Zero for Conduct at the TCM Movie Database

- Zero for Conduct at AllMovie

- "Zéro de conduite: Rude Freedom" by B. Kite. Criterion Collection Essay

- Zéro de conduite (English subtitles) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive