Emiliano Zapata Salazar (Spanish pronunciation: [emiˈljano saˈpata]; August 8, 1879 – April 10, 1919) was a Mexican revolutionary. He was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920, the main leader of the people's revolution in the Mexican state of Morelos, and the inspiration of the agrarian movement called Zapatismo.

Emiliano Zapata | |

|---|---|

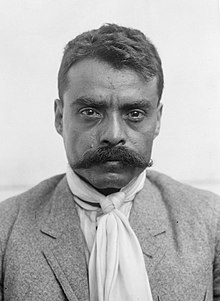

Zapata in 1914 | |

| Nickname(s) | El Caudillo del Sur, Attila of the South, and "E", Mr. Rebel by Woodrow Wilson |

| Born | August 8, 1879 Anenecuilco, Morelos, Mexico |

| Died | April 10, 1919 (aged 39) Chinameca, Morelos, Mexico |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | Mexico (Zapatismo revolutionary forces) |

| Years of service | 1910–1919 |

| Rank | General |

| Commands | Liberation Army of the South |

| Battles / wars | Mexican Revolution |

| Signature |  |

Zapata was born in the rural village of Anenecuilco in Morelos, in an era when peasant communities came under increasing repression from the small-landowning class who monopolized land and water resources for sugarcane production with the support of dictator Porfirio Díaz (President from 1877 to 1880 and 1884 to 1911). Zapata early on participated in political movements against Díaz and the landowning hacendados, and when the Revolution broke out in 1910 he became a leader of the peasant revolt in Morelos. Cooperating with a number of other peasant leaders, he formed the Liberation Army of the South, of which he soon became the undisputed leader. Zapata's forces contributed to the fall of Díaz, defeating the Federal Army in the Battle of Cuautla in May 1911, but when the revolutionary leader Francisco I. Madero became president he disavowed the role of the Zapatistas, denouncing them as mere bandits.

In November 1911, Zapata promulgated the Plan de Ayala, which called for substantial land reforms, redistributing lands to the peasants. Madero sent the Federal Army to root out the Zapatistas in Morelos. Madero's generals employed a scorched-earth policy, burning villages and forcibly removing their inhabitants, and drafting many men into the Army or sending them to forced-labor camps in southern Mexico. Such actions strengthened Zapata's standing among the peasants, and succeeded in driving the forces of Madero, led by Victoriano Huerta, out of Morelos. In a coup against Madero in February 1913, Huerta took power in Mexico, but a coalition of Constitutionalist forces in northern Mexico, led by Venustiano Carranza, Álvaro Obregón and Francisco "Pancho" Villa, ousted him in July 1914 with the support of Zapata's troops. Zapata did not recognize the authority that Carranza asserted as leader of the revolutionary movement, continuing his adherence to the Plan de Ayala.

In the aftermath of the revolutionaries' victory over Huerta, they attempted to sort out power relations in the Convention of Aguascalientes (October to November 1914). Zapata and Villa broke with Carranza, and Mexico descended into a civil war among the winners. Dismayed with the alliance with Villa, Zapata focused his energies on rebuilding society in Morelos (which he now controlled), instituting the land reforms of the Plan de Ayala. As Carranza consolidated his power and defeated Villa in 1915, Zapata initiated guerrilla warfare against the Carrancistas, who in turn invaded Morelos, employing once again scorched-earth tactics to oust the Zapatista rebels. Zapata re-took Morelos in 1917 and held most of the state against Carranza's troops until he was killed in an ambush in April 1919. After his death, Zapatista generals aligned with Obregón against Carranza and helped drive Carranza from power. In 1920, Zapatistas obtained important positions in the government of Morelos after Carranza's fall, instituting many of the land reforms envisioned by Zapata.

Zapata remains an iconic figure in Mexico, used both as a nationalist symbol as well as a symbol of the neo-Zapatista movement. Article 27 of the 1917 Mexican Constitution was drafted in response to Zapata's agrarian demands.[1]

Life and career

edit1879–1909: Early life

editEmiliano Zapata was born to Gabriel Zapata and Cleofas Jertrudiz Salar of Anenecuilco, Morelos, the ninth of ten children.[a] Contrary to popular legend, the Zapatas were a well-known local family and reasonably well-off.[2] Emiliano's maternal grandfather, José Salazar, had served in the army of José María Morelos y Pavón during the siege of Cuautla, while his paternal uncles Cristino and José Zapata fought in the Reform War and the French Intervention. Emiliano's godfather was the manager of a large local hacienda and his godmother was the manager's wife.[3] The Zapata family were descended from the Zapata of Mapaztlán and were likely mestizos, Mexicans of both Spanish and Nahua heritage.[4][5] Although it is not known conclusively whether Zapata himself spoke Nahuatl, historian Miguel León-Portilla has cited later Zapatista proclamations and eyewitness accounts to argue that he was fluent in the language.[6][7]

Gabriel Zapata was a farmer and horse trainer, and Emiliano's upbringing on the farm gave him an intimate familiarity with the difficulties of the countryside and his village's long struggle to regain the land taken by expanding haciendas.[8] He received a limited education from his teacher, Emilio Vara, but it included "the rudiments of bookkeeping".[9] Gabriel died when Emiliano was about 16 or 17, leaving the latter to care for his family. Emiliano was entrepreneurial and bought a team of mules to haul maize from farms to town and bricks to the Hacienda of Chinameca; he was also a successful farmer, growing watermelons as a cash crop. He was a skilled horseman and competed in rodeos and races, as well as bullfighting from horseback.[10] These skills as a horseman brought him work as a horse trainer for Porfirio Díaz's son-in-law, Ignacio de la Torre y Mier who had a large sugar hacienda nearby. Emiliano had a striking appearance, with a large mustache in which he took pride, and good quality clothing described by his loyal secretary: "General Zapata's dress until his death was a charro outfit: tight-fitting black cashmere pants with silver buttons, a broad charro hat, a fine linen shirt or jacket, a scarf around his neck, boots of a single piece, Amozoqueña-style spurs, and a pistol at his belt."[10] In an undated studio photo, Zapata is dressed in a standard business suit and tie, projecting an image of a man of means.

Around the turn of the 20th century, Anenecuilco was a mixed Spanish-speaking mestizo and indigenous Nahuatl-speaking town. It had a long history of protesting the local haciendas taking community members' land, and its leaders gathered colonial-era documentation of their land titles to prove their claims.[11] Some of the colonial documentation was in Nahuatl, with contemporary translations to Spanish for use in legal cases in the Spanish courts.[12] As referenced above, one eyewitness account by Luz Jiménez of Milpa Alta states that Emiliano Zapata spoke Nahuatl fluently when his forces arrived in her community.[13]

Community members in Anenecuilco, including Zapata, sought redress against land seizures. In 1892, a delegation had an audience with Díaz, who with the intervention of a lawyer, agreed to hear them. Although promising them to deal favorably with their petition, Díaz had them arrested and Zapata was conscripted into the Federal Army.[14] Under Díaz, conscription into the Federal Army was much feared by ordinary Mexican men and their families. Zapata was one of many rebel leaders who were conscripted at some point.[15]

1909–1910: First political forays

editIn 1909, an important meeting was called by the elders of Anenecuilco, whose chief elder was José Merino. He announced "my intention to resign from my position due to my old age and limited abilities to continue the fight for the land rights of the village." The meeting was used as a time for discussion and nomination of individuals as a replacement for Merino as the president of the village council. The elders on the council were so well respected by the village men that no one would dare to override their nominations or vote for an individual against the advice of the current council at that time. The nominations made were Modesto González, Bartolo Parral, and Emiliano Zapata. After the nominations were closed, a vote was taken and Zapata became the new council president without contest.[16]

Although Zapata had turned 30 only a month before, voters knew that it was necessary to elect someone respected by the community who would be responsible for the village. Even though he was relatively young, Anenecuilco was ready to hand over the leadership to him without any worry of failure. Before he was elected he had shown the village his nature by helping to lead a campaign in opposition to the candidate Díaz had chosen governor. Even though Zapata's efforts failed, he was able to create and cultivate relationships with political authority figures that would prove useful for him.[16]

Zapata became a leading figure in the village of Anenecuilco, where his family had lived for many generations, though he did not take the title of Don, as was custom for someone of his status. Instead, the Anenecuilcans referred to Zapata affectionately as "Miliano" and later as pobrecito (poor little thing) after his death.[17]

Mexican Revolution

edit1910–1912: Maderista revolution and plan of Ayala

editThe flawed 1910 elections were a major reason for the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910. Porfirio Díaz was being threatened by the candidacy of Francisco I. Madero. Zapata, seeing an opportunity to promote land reform in Mexico,[19] joined with Madero and his Constitutionalists, who included Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa,[20] whom he perceived to be the best chance for genuine change in the country. Although he was wary of Madero, Zapata cooperated with him when Madero made vague promises about land reform in his Plan of San Luis Potosí. Land reform was the central feature of Zapata's political vision.[21]

Zapata joined Madero's campaign against President Díaz.[22] The first military campaign of Zapata was the capture of the Hacienda of Chinameca. When Zapata's army captured Cuautla after a six-day battle on May 19, 1911,[21] it became clear that Díaz would not hold on to power for long.[22]

During his interim presidency, Francisco León de la Barra tasked General Victoriano Huerta to suppress revolutionaries in Morelos. Huerta was to disarm revolutionaries peacefully if possible, but could use force. In August 1911, Huerta led 1,000 Federal troops to Cuernavaca, which Madero saw as provocative. Writing the Minister of the Interior, Zapata demanded the Federal troops withdraw from Morelos, saying "I won't be responsible for the blood that is going to flow if the Federal forces remain."[23]

Although Madero's Plan of San Luis Potosí specified the return of village land and won the support of peasants seeking land reform, he was not ready to implement radical change. Madero simply demanded that "Public servants act 'morally' in enforcing the law ...". Upon seeing the response by villagers, Madero offered formal justice in courts to individuals who had been wronged by others with regard to agrarian politics. Zapata decided that on the surface it seemed as though Madero was doing good things for the people of Mexico, but Zapata did not know the level of sincerity in Madero's actions and thus did not know if he should support him completely.[24]

Compromises between the Madero and Zapata failed in November 1911, days after Madero was elected president. Zapata and Otilio Montaño Sánchez, a former school teacher, fled to the mountains of southwest Puebla. There they promulgated the most radical reform plan in Mexico, the Plan de Ayala (Plan of Ayala). The plan declared Madero a traitor, named as head of the revolution Pascual Orozco, the victorious general who captured Ciudad Juárez in 1911 forcing the resignation of Díaz. He outlined a plan for true land reform.[22]

Zapata had supported the ouster of Díaz and had the expectation that Madero would fulfill the promises made in the Plan of San Luis Potosí to return village lands. He did not share Madero's vision of democracy built on particular freedoms and guarantees that were meaningless to peasants:

Freedom of the press for those who cannot read; free elections for those who do not know the candidates; proper legal for those who have anything to do with an attorney. All those democratic principles, all those great words that gave such joy to our fathers and grandfathers have lost their magic for the people ... With or without elections, with or without an effective law, with the Porfirian dictatorship or with Madero's democracy with a controlled or free press, its fate remains the same.[25]

The 1911 Plan of Ayala called for all lands stolen under Díaz to be immediately returned; there had been considerable land fraud under the old dictator, so a great deal of territory was involved. It also stated that large plantations owned by a single person or family should have one-third of their land nationalized, which would then be required to be given to poor farmers. It also argued that if any large plantation owner resisted this action, they should have the other two-thirds confiscated as well. The Plan of Ayala also invoked the name of President Benito Juárez, one of Mexico's great liberal leaders, and compared the taking of land from the wealthy to Juarez's actions when land was expropriated from the Catholic church during the Liberal Reform.[27] Another part of the plan stated that rural cooperatives and other measurements should be put in place to prevent the land from being seized or stolen in the future.[28]

In the following weeks, the development of military operations "betray(ed) good evidence of clear and intelligent planning."[29] During Orozco's rebellion, Zapata fought Mexican troops in the south near Mexico City.[22] In the original design of the armed force, Zapata was a mere colonel among several others; however, the true plan that came about through this organization lent itself to Zapata. Zapata believed that the best route of attack would be to center the fighting and action in Cuautla. If this political location could be overthrown, the army would have enough power to "veto anyone else's control of the state, negotiate for Cuernavaca or attack it directly, and maintain independent access to Mexico City as well as escape routes to the southern hills."[29] However, in order to gain this great success, Zapata realized that his men needed to be better armed and trained.

The first line of action demanded that Zapata and his men "control the area behind and below a line from Jojutla to Yecapixtla."[29] When this was accomplished it gave the army the ability to complete raids as well as wait. As the opposition of the Federal Army and police detachments slowly dissipated, the army would be able to eventually gain powerful control over key locations on the Interoceanic Railway from Puebla City to Cuautla. If these feats could be completed, it would gain access to Cuautla directly and the city would fall.[30]

The plan of action was carried out successfully in Jojutla. However, Pablo Torres Burgos, the commander of the operation, was disappointed that the army disobeyed his orders against looting and ransacking. The army took complete control of the area, and it seemed as though Torres Burgos had lost control over his forces prior to this event. Shortly after, Torres Burgos called a meeting and resigned from his position. Upon leaving Jojutla with his two sons, he was surprised by a federal police patrol who subsequently shot all three of the men on the spot.[30] This seemed to some to be an ending blow to the movement, because Torres Burgos had not selected a successor for his position; however, Zapata was ready to take up where Torres Burgos had left off.[30]

Shortly after Torres Burgos's death, a party of rebels elected Zapata as "Supreme Chief of the Revolutionary Movement of the South".[31] This seemed to be the fix to all of the problems that had just arisen, but other individuals wanted to replace Zapata as well. Due to this new conflict, the individual who would come out on top would have to do so by "convincing his peers he deserved their backing."[32]

Zapata finally gained the support necessary by his peers and was considered a "singularly qualified candidate".[32] This decision to make Zapata the leader of the revolution in Morelos did not occur all at once, nor did it ever reach a true definitive level of recognition. In order to succeed, Zapata needed a strong financial backing for the battles to come. This came in the form of 10,000 pesos delivered by Rodolfo from the Tacubayans.[33] Due to this amount of money Zapata's group of rebels became one of the strongest in the state financially.

After a period Zapata became the leader of his "strategic zone", which gave him power and control over the actions of many more individual rebel groups and thus greatly increased his margin of success. "Among revolutionaries in other districts of the state, however, Zapata's authority was more tenuous."[34] After a meeting between Zapata and Ambrosio Figueroa in Jolalpan, it was decided that Zapata would have joint power with Figueroa with regard to operations in Morelos. This was a turning point in the level of authority and influence that Zapata had gained and proved useful in the direct overthrow of Morelos.[30]

1913–1914: opposition to Victoriano Huerta

editIf there was anyone that Zapata hated more than Díaz and Madero, it was Victoriano Huerta, the bitter, violent alcoholic who had been responsible for many atrocities in southern Mexico while trying to end the rebellion. Zapata was not alone: in the north, Pancho Villa, who had supported Madero, immediately took to the field against Huerta.[22] Zapata revised the Plan of Ayala and named himself the leader of his revolution.[27] He was joined by two newcomers to the Revolution, Venustiano Carranza and Alvaro Obregón, who raised large armies in Coahuila and Sonora respectively. Together they made short work of Huerta, who resigned and fled in June 1914 after repeated military losses.[22]

1914–1919: The conventionist government

editOn April 21, 1914, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson sent a contingent of troops to occupy the port city of Veracruz. This sudden threat caused Huerta to withdraw his troops from Morelos and Puebla, leaving only Jojutla and Cuernavaca under federal control. Zapatistas quickly assumed control of eastern Morelos, taking Cuautla and Jonacatepec with no resistance. In spite of being faced with a possible foreign invasion, Zapata refused to unite with Huerta in defense of the nation. He stated that if need be he would defend Mexico alone as chief of the Ayalan forces.[35] In May the Zapatistas took Jojutla from the Federal Army, many of whom joined the rebels, and captured guns and ammunition. They also laid siege to Cuernavaca where a small contingent of federal troops were holed up.[36] By the summer of 1915, Zapata's forces had taken the southern edge of the Federal District, occupying Milpa Alta and Xochimilco, and were poised to move into the capital. In mid July, Huerta was forced to flee as a Constitutionalist force under Carranza, Obregón, and Villa took the Federal District.[37] The Constitutionalists established a peace treaty, inserting Carranza as First Authority of the nation. Carranza, an aristocrat with politically relevant connections, then gained the backing of the US, which passed over Villa and Zapata due to their lower-status backgrounds and more progressive ideologies.[38] In spite of having contributed decisively to the fall of Huerta, the Zapatistas were left out of the peace treaties, probably because of Carranza's intense dislike for the Zapatistas, whom he saw as uncultured savages.[39] Through 1915 there was a tentative peace in Morelos and the rest of the country.

As the Constitutionalist forces began to split, with Villa creating a popular front against Carranza's Constitutionalists, Carranza worked diplomatically to get the Zapatistas to recognize his rule, sending Dr. Atl as an envoy to propose a compromise with Zapata. For Carranza, an agreement with Zapata would mean that he did not need to worry about his force's southern flank and could concentrate on defeating Villa. Zapata demanded veto power over Carranza's decisions, which Carranza rejected, and negotiations broke off.[41] Zapata issued a statement, perhaps drafted by his advisor, Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama.

The country wishes to destroy feudalism once and for all [while Carranza offers] administrative reform ... complete honesty in the handling of public monies ... freedom of the press for those who cannot read; free elections for those who do not know the candidates; proper legal proceedings for those who have never had anything to do with an attorney. All those beautiful democratic principles, all those great words that give such joy to our fathers and grandfathers have lost their magic ... The people continue to suffer from poverty and endless disappointments.[42]

Unable to reach an agreement, the Constitutionalists divided along ideological lines, with Zapata and Villa leading a progressive rebellion, and Carranza and Obregón leading the conservative faction of the remaining Constitutionalists.[38] Villa and the other anti-Carrancista leaders of the North established the Convention of Aguascalientes against Carranza. Zapata and his envoys got the convention to adopt some of the agrarian principles of the Plan de Ayala.[43] Zapata and Villa met in Xochimilco to negotiate an alliance and divide the responsibility for ridding Mexico of the remaining Carrancistas. The meeting was awkward but amiable, and was widely publicized. It was decided that Zapata should work on securing the area east of Morelos from Puebla towards Veracruz. Nonetheless, during the ensuing campaign in Puebla, Zapata was disappointed by Villa's lack of support. Villa did not initially provide the Zapatistas with the weaponry they had agreed on and, when he did, he did not provide adequate transportation. There were also a series of abuses by Villistas against Zapatista soldiers and chiefs. These experiences led Zapata to grow unsatisfied with the alliance, turning instead his efforts to reorganizing the state of Morelos that had been left in shambles by the onslaught of Huerta and Robles. Having taken Puebla, Zapata left a couple of garrisons there but did not support Villa further against Obregón and Carranza. The Carrancistas saw that the rebel alliance was divided and decided to concentrate on beating Villa, which left the Zapatistas to their own devices for a while.[44]

Through 1915, Zapata began reshaping Morelos after the Plan de Ayala, redistributing hacienda lands to the peasants, and largely letting village councils run their own local affairs. Most peasants did not turn to cash crops, instead growing subsistence crops such as corn, beans, and vegetables. The result was that as the capital was starving, while the peasants had more to eat than they had had in 1910 and at lower prices. The only official event in Morelos during this entire year was a bullfight in which Zapata himself and his nephew Amador Salazar participated. 1915 was a short period of peace and prosperity for the farmers of Morelos, in between the massacres of the Huerta era and the civil war of the winners to come.[45]

Even when Villa was retreating, having lost the Battle of Celaya in 1915, and Obregón took the capital from the Conventionists, who retreated to Toluca, Zapata did not open a second front.

When Carranza's forces were poised to move into Morelos, Zapata took action. He attacked Carrancista positions with large forces, trying to harry the Carrancistas in the rear as they were occupied with routing Villa throughout the Northwest. Though Zapata managed to take many important sites such as the Necaxa power plant that supplied Mexico City, he was unable to hold them. The Convention was finally routed from Toluca, and Carranza was recognized by US President Woodrow Wilson as the head of state of Mexico in October.[46]

Through 1916, Zapata attacked federal forces from Hidalgo to Oaxaca, and Genovevo de la O fought the Carrancistas in Guerrero. The Zapatistas attempted to amass support for their cause by promulgating new manifestos against the hacendados, but this had little effect since the hacendados had already lost power throughout the country.[47]

Having been put in charge of the efforts to root out Zapatismo in Morelos, Pablo González Garza was humiliated by Zapata's counterattacks and enforced increasingly draconian measures against the locals. He received no reinforcements, as Obregón, the Minister of War, needed all his forces against Villa in the north and against Felix Díaz in Oaxaca. Through low-scale attacks on Gonzalez's positions, Zapata drove Gonzalez out of Morelos by the end of 1916.[48]

Nonetheless, outside of Morelos, the revolutionary forces started disbanding. Some rebels (such as Domingo Arenas) joined the constitutionalists,while others lapsed into banditry. In Morelos, Zapata once more reorganized the Zapatista state, continuing with democratic reforms and legislation meant to keep the civil population safe from abuses by soldiers. Though his advisers urged him to mount a concerted campaign against the Carrancistas across southern Mexico, again he concentrated entirely on stabilizing Morelos and making life tolerable for the peasants.[49] Meanwhile, Carranza mounted national elections in all state capitals except Cuernavaca, and promulgated the 1917 Constitution which incorporated elements of the Plan de Ayala.

Meanwhile, the disintegration of the revolution outside of Morelos put pressure on the Zapatistas. When Arenas went over to the constitutionalists, he secured peace for his region and remained in control there. This suggested to many revolutionaries that perhaps the time had come to seek a peaceful conclusion to the struggle. A faction within the Zapatista ranks, led by former General Vazquez and Zapata's erstwhile adviser and inspiration Otilio Montaño, moved against the Tlaltizapan headquarters, demanding surrender to the Carrancistas. Reluctantly, Zapata had Montaño tried for treason and executed.[50]

Zapata began looking for allies among the northern revolutionaries and the southern Felicistas, followers of the Liberalist Felix Díaz. He sent Gildardo Magaña as an envoy to communicate with the Americans and other possible sources of support. In the fall of 1917 a force led by Gonzalez and ex-Zapatista Sidronio Camacho, who had killed Zapata's brother Eufemio, moved into the eastern part of Morelos, taking Cuautla, Zacualpan, and Jonacatepec.

Zapata continued to try to unite the national anti-Carrancista movement through the next year, and the constitutionalists did not make further advances. In the winter of 1918, severe cold weather and the onset of the Spanish flu caused the loss of a quarter of the total population of the state, almost as many as had been lost to Huerta in 1914.[51] Furthermore, Zapata began to worry that with the end of World War I, the US would turn its attention to Mexico, forcing the Zapatistas either to join the Carrancistas in a national defense or acquiesce to foreign domination of Mexico.

In December 1918, Carrancistas under Gonzalez undertook an offensive campaign, taking most of the state of Morelos, and pushing Zapata to retreat. The main Zapatista headquarters was moved to Tochimilco, Puebla, although Tlaltizapan also remained under Zapatista control. Through Castro, Carranza issued offers to the main Zapatista generals to join the nationalist cause, with pardon. But apart from Manuel Palafox, who having fallen in disgrace among the Zapatistas had joined the Arenistas, none of the major generals did.[52]

Zapata released statements accusing Carranza of being secretly sympathetic to Germany.[53] In March, Zapata finally sent an open letter to Carranza, urging him for the good of the fatherland to resign his leadership to Vazquez Gómez, by now the rallying point of the anti-constitutionalist movement.[54] Having issued this formidable moral challenge to Carranza prior to the upcoming 1920 presidential elections, Zapata was urged by Zapatista generals at Tochimilco, Magaña, and Ayaquica not to take any risks and lie low. But Zapata declined, considering that the respect of his troops depended on his active presence at the front.[55]

Personal life

editChildren

editAs far as is known, Zapata fathered a total of 16 documented children with 9 women, but it has also been commented that there were actually 14 women with whom he had relationships.[56]

- With Inés Alfaro Aguilar he procreated his first five documented children: Guadalupe, Nicolás, Juan, Ponciano and María Elena.[56]

- When the Porfirian dictatorship fell, on August 20, 1911, he married Miss Josefa Espejo Merino known as "La Generala" (San Miguel de Anenecuilco, Wednesday March 19, 1879 – Villa de Ayala, Friday, August 8, 1968),[56] daughter of Don Fidencio Espejo and Guadalupe Sánchez Merino, with whom he had two children. The first, a boy named Felipe Zapata Espejo, was born around 1912 on El Jilguero hill and died at the age of five, around 1917, in one of the many shelters that the family had, after being bitten by a rattlesnake.[56] The second child was a girl, Josefa Zapata Espejo, born around 1913 in Tlaltizapán and who died a year before Felipe, around 1916, as a result of a scorpion sting.[56]

- With Margarita Sáenz Ugalde (July 23, 1899, in Yautepec, Morelos – March 17, 1974, in Mexico City),[56] he had three children: Luis Eugenio (December 2, 1914, in Tlapehuala, Guerrero – October 10, 1979, in Mexico City), Margarita and Gabriel Zapata Sáenz, the latter two of whom died shortly after birth.[56]

- With Petra Portillo Torres,[57] he had a daughter, Ana María Zapata Portillo, born on June 22, 1915, in Cuautla. She was aware of her father's legacy from a very early age, and this made her continue his work of dedication to agrarian rights, serving as treasurer of the ejido of Cuautla, as ejidataria of Cuautla, as municipal councilor and municipal trustee.[58] She died on February 28, 2010, in Cuautla, and was buried in the Municipal Pantheon of Cuautla.[56]

- With María de Jesús Pérez Caballero, native of Coahuixtla, he had Mateo Emiliano Zapata Pérez, who was born on September 21, 1917, in Temilpa Viejo, Tlaltizapán, Morelos, and died on January 10, 2007, in Cuautla. He was buried in the Cuautla Municipal Pantheon.[56]

- With Georgina Piñeiro, he had Diego Zapata Piñeiro, who was born in Tlaltizapán on December 13, 1916, and died on December 20, 2008, in Mexico City. He was buried in the Cuautla Municipal Pantheon.[56]

- With Gregoria Zúñiga Benítez, he had María Luisa Zapata Zúñiga, born in Quilamula, Morelos, on June 21, 1916, and died in 1935 of meningitis, leaving no descendants.[56]

- He did not leave descendants with Luz Zúñiga Benítez, although according to historian Carlos Barreto Mark, there is a version that she had a child, who apparently died at birth.[56]

- With Agapita Sánchez, he had Carlota Zapata Sánchez, born in Huitzilac, Morelos, in 1913 and died in Jiutepec, Morelos, on April 22, 2014, aged 100.[59]

- With Matilde Vázquez, he had Gabriel Zapata Vázquez.[56]

There is a version of the existence of another son, José Zapata, of an unknown mother, but the validity of the latter is not fully proven.[56]

Sexuality

editAccording to the book The Album of Amada Díaz written by Ricardo Orozco and based on the diaries of Amada Díaz, daughter of Porfirio Díaz, Zapata had a very good friendship with Ignacio de la Torre y Mier, Amada's husband.[60] The friendship between the two has been questioned over time, and it has been said that Zapata and Mier had an affair.[60] As stated in the aforementioned work, it is said that both met in 1906, when the revolutionary worked in the stables of the Hacienda de San Carlos Borromeo.[61] It was not openly known, but Mier was homosexual, so when he met Zapata he fell in love with him and decided to take him to work at his ranch located in Mexico City. Once there, the book cites that in words written by Amada Díaz, she saw them "wallowing in the stables".[61][62]

Some time after this, as De la Torre y Mier was a politician and businessman, the Mexican Revolution represented a problem for him, this being one of the reasons why he would finance a fight that would try to eradicate the movement.[61] The efforts were useless, since in the end the Revolution managed to triumph. Subsequently, Venustiano Carranza, one of its leaders, ordered Mier's imprisonment. Taking the alleged relationship he had with Zapata as a background, it has been said that it could have been a kind of "gay love gesture" that Zapata had with him, because thanks to the intervention of the aforementioned, he managed to be given freedom and escape from imprisonment.[61][62] With this history, it has been concluded that he may have been a bisexual man.[61]

Other people who have talked about this include Pedro Ángel Palou, as in his novel Zapata insinuates that Zapata had some homosexual relations. The latter was based on testimonies told by Manuel Palafox «El Ave Negra», who was the trusted emissary,[63][64] personal secretary,[65] and one of the closest revolutionaries to Zapata,[63] who additionally was secretly gay.[66] Zapata was aware of his preferences and had no problems with it, but since he was governed by the principle of executing those who were too "feminine", and Palafox behaved in this way, little by little the rumor about the homosexuality of his revolutionary companion was gaining strength among his troops, and finally in 1918, he found it necessary to remove him from his post as general and main Zapatista emissary.[67]

Assassination

editEliminating Zapata was a top priority for President Carranza. Carranza was unwilling to compromise with domestic foes and wanted to demonstrate to Mexican elites and to American interests that Carranza was the "only viable alternative to both anarchy and radicalism."[68] In mid-March 1919, General Pablo González ordered his subordinate Jesús Guajardo to begin operations against the Zapatistas in the mountains around Huautla. But when González later discovered Guajardo carousing in a cantina, he had him arrested, and a public scandal ensued.

On March 21, Zapata attempted to smuggle in a note to Guajardo, inviting him to switch sides. The note, however, never reached Guajardo but instead wound up on González's desk. González devised a plan to use this note to his advantage. He accused Guajardo of not only being a drunk, but of being a traitor. After reducing Guajardo to tears, González explained to him that he could recover from this disgrace if he feigned a defection to Zapata. So Guajardo wrote to Zapata telling him that he would bring over his men and supplies if certain guarantees were promised.[69] Zapata answered Guajardo's letter on April 1, 1919, agreeing to all of Guajardo's terms.

Zapata suggested a mutiny on April 4. Guajardo replied that his defection should wait until a new shipment of arms and ammunition arrived sometime between the 6th and the 10th. By the 7th, the plans were set: Zapata ordered Guajardo to attack the Federal garrison at Jonacatepec because the garrison included troops who had defected from Zapata. Pablo González and Guajardo notified the Jonacatepec garrison ahead of time, and a mock battle was staged on April 9. At the conclusion of the mock battle, the former Zapatistas were arrested and shot. Convinced that Guajardo was sincere, Zapata agreed to a final meeting where Guajardo would defect.[70]

On April 10, 1919, Guajardo invited Zapata to a meeting, intimating that he intended to defect to the revolutionaries.[22] However, when Zapata arrived at the Hacienda de San Juan, in Chinameca, Ayala municipality, Guajardo's men riddled him with bullets.

Zapata's body was photographed, displayed for 24 hours, and then buried in Cuautla.[71] Pablo González wanted the body photographed, so that there would be no doubt that Zapata was dead: "it was an actual fact that the famous jefe of the southern region had died."[72] Although Mexico City newspapers had called for Zapata's body to be brought to the capital, Carranza did not do so. However, Zapata's clothing was displayed outside a newspaper's office across from the Alameda Park in the capital.[72]

Immediate aftermath

editAlthough Zapata's assassination weakened his forces in Morelos, the Zapatistas continued the fight against Carranza.[68] For Carranza the death of Zapata was the removal of an ongoing threat, for many Zapata's assassination undermined "worker and peasant support for Carranza and Pablo González."[73] Obregón seized on the opportunity to attack Carranza and González, Obregón's rival candidate for the presidency, by saying "this crime reveals a lack of ethics in some members of the government and also of political sense, since peasant votes in the upcoming election will now go to whoever runs against Pablo González."[73]

In spite of González's attempts to sully the name of Zapata and the Plan de Ayala during his 1920 campaign for the presidency,[74] the people of Morelos continued to support Zapatista generals, providing them with weapons, supplies and protection. Carranza was wary of the threat of U.S. intervention, and Zapatista generals decided to take a conciliatory approach. Bands of Zapatistas started surrendering in exchange for amnesties, and many Zapatista generals went on to become local authorities, such as Fortino Ayaquica who became municipal president of Tochimilco.[30] Other generals such as Genovevo de la O remained active in small-scale guerrilla warfare.

As Venustiano Carranza moved to curb his former allies and now rivals in 1920 to impose a civilian, Ignacio Bonillas, as his successor in the presidency, Obregón sought to align himself with the Zapatista movement against that of Carranza. Genovevo de la O and Magaña supported him in the coup by former Constitutionalists, fighting in Morelos against Carranza and helping prompt Carranza to flee Mexico City toward Veracruz in May 1920. "Obregón and Genovevo de la O entered Mexico City in triumph."[75]

Zapatistas were given important posts in the interim government of Adolfo de la Huerta and the administration of Álvaro Obregón, following his election to the presidency after the coup. Zapatistas had almost total control of the state of Morelos, where they carried out a program of agrarian reform and land redistribution based on the provisions of the Plan de Ayala and with the support of the government.

According to "La Demócrata", after Zapata's assassination, "in the consciousness of the natives", Zapata "had taken on the proportions of a myth" because he had "given them a formula of vindication against old offenses."[76] Mythmaking would continue for decades after Zapata was gunned down.

Legacy

editZapata's influence continues to this day, particularly in revolutionary tendencies in southern Mexico. In the long run, he has done more for his ideals in death than he did in life. He came to be viewed as a martyr to the cause of land reform after his murder. Even though Mexico still has not implemented the sort of land reform he wanted, he is remembered as a visionary who fought for his countrymen.[22]

Zapata's Plan of Ayala influenced Article 27 of the progressive 1917 Constitution of Mexico that codified an agrarian reform program.[77] Even though the Mexican Revolution did restore some land that had been taken under Díaz, the land reform on the scale imagined by Zapata was never enacted.[27] However, a great deal of the significant land distribution which Zapata sought would later be enacted after Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas took office in 1934.[77][78] Cárdenas would fulfill not only the land distribution policies written in Article 27, but other reforms written in the Mexican Constitution as well.[79]

There are controversies about the portrayal of Emiliano Zapata and his followers, whether they were bandits or revolutionaries.[80] At the outbreak of the Revolution, "Zapata's agrarian revolt was soon construed as a 'caste war' [race war], in which members of an 'inferior race' were captained by a 'modern Attila'".[81]

Zapata is now one of the most revered national heroes of Mexico. To many Mexicans, especially the peasant and indigenous citizens, Zapata was a practical revolutionary who sought the implementation of liberties and agrarian rights outlined in the Plan of Ayala. He was a realist with the goal of achieving political and economic emancipation of the peasants in southern Mexico and leading them out of severe poverty.[30]

Many popular organizations take their name from Zapata, most notably the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional or EZLN in Spanish), the Neozapatismo group that emerged in the state of Chiapas in 1983 and precipitated the 1994 indigenous Zapatista uprising which still continues in Chiapas. Towns, streets, and housing developments called "Emiliano Zapata" are common across the country and he has, at times, been depicted on Mexican banknotes.[82]

According to Eric Wolf, Zapata and his movement have also been credited with contributing towards Christian socialism and liberation theology.[83] Zapata and his agrarian revolutionaries fought under the emblem of Virgin of Guadalupe,[83] which highlighted the Catholic nature of the movement.[84] Unlike the Constitutionalists and Obregonistas, Zapata's revolutionary faction was considered friendly towards the Catholic Church.[85] As the followers of Zapata were committed Catholics and were known for tucking pictures of Virgin Mary into their hats for protection,[86] many Cristeros strongly admired Zapata during the Cristero War.[87]

Damariz Posadas named Zapatismo "an example of a Marian movement being shaped by liberation theology", noting the connection between the Zapatist Marian message that "the natives as the chosen people" and the central concept of liberation theology, the "preferential option for the poor". Zapata recognized the indigenous as the poor of México and promoted a culture of a revolution against poverty. The Neo-Zapatistas that followed the legacy of Zapata kept the Marian roots of his movement, and the Catholic Church became politically involved with the Neo-Zapatistas in the 1960s, further shaping their ideology. One Zapatista fighter remarked: "We all wanted change, we prayed, it helped but it did not solve anything. The church helps us fight. Yes, we use weapons. but not always. Right now, we focus on changing the government and changing the laws to help people."[88]

Zapata left a profound influence on Mexican natives, and his movement became a defining feature of the morelense culture. His agrarian struggle has a primary role in the collective memory of Morelos and local religious festivals incorporate him "on an almost equal level with saint". Zapata's ventures were attributed to the intervention from patron saints, and Zapatista veterans became the secular complement of local cult of saints, as they became “both symbols of the ideals, the wishes, of the group.” In other regions such as Chiapas and Tepoztlán, Zapata is also worshipped as a reincarnated Mayan deity - Votán Zapata.[89]

Modern activists in Mexico frequently make reference to Zapata in their campaigns; his image is commonly seen on banners, and many chants invoke his name: Si Zapata viviera con nosotros anduviera ("If Zapata lived, he would walk with us"), and Zapata vive, la lucha sigue ("Zapata lives; the struggle continues").

The tomb of Zapata is located in Cuautla, Morelos, and every year several festivities are held around the anniversary of his death.

The fossil reptile Zapatadon (Rhynchocephalia) was named after him.[90]

In popular culture

editZapata has been depicted in movies, comics, books, music, and clothing. For example, there was the stage musical Zapata (1980), written by Harry Nilsson and Perry Botkin, with a libretto by Allan Katz, which ran for 16 weeks at the Goodspeed Opera House in East Haddam, Connecticut. A movie called Zapata: El sueño de un héroe (Zapata: A Hero's Dream) was produced in 2004, starring Mexican actors Alejandro Fernandez, Jaime Camil, and Lucero. There is also a sub-genre of the Spaghetti Western called the Zapata Western, which features stories set during the Mexican Revolution.

Marlon Brando played Emiliano Zapata in the award-winning movie based on his life, Viva Zapata! in 1952. The film co-starred Anthony Quinn, who won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor in the role of Zapata's brother. The director was Elia Kazan and the writer was John Steinbeck.

Emiliano Zapata is a major character in The Friends of Pancho Villa (1996), by James Carlos Blake

Emiliano Zapata is referenced in the songs "Calm Like a Bomb" by American rock band Rage Against the Machine from their album "The Battle of Los Angeles." and "Zapata's Blood" from their album "The Battle of Mexico City". Zapata is also referenced in the song "Veracruz" by Warren Zevon which is about the Mexican revolution and the invasion of Veracruz.

In the 2011 Mexican TV series El Encanto del Aguila Zapata is played by the Mexican actor Tenoch Huerta.

In December 2019, an arts show commemorating the 100 year anniversary of his death was held at the Palacio de Bellas Artes. The show featured 141 works.[91] A painting called La Revolución depicted Zapata as intentionally effeminate,[92] riding an erect horse, nude except for high heels and a pink hat. According to the artist, he created the painting to combat machismo. The painting caused protests from the farmer's union and admirers of Zapata. His grandson Jorge Zapata González threatened to sue if the painting was not removed. There was a clash between supporters of the painting and detractors at the museum. A compromise was reached with some of Zapata's family, a label was placed next to the painting outlining their disagreement with the painting.[93]

Sobriquets

editGallery

edit-

Emiliano Zapata and followers of the Liberation Army of the South, undated photo.

-

Emiliano Zapata enters Cuernavaca in April 1911. Federal General Manuel Asúnsolo turns the city over to the Zapatistas

-

Zapata and Villa with their joint forces enter Xochimilco in December 1914.

-

Zapatistas at upscale Sanborn's in Mexico City

-

General Emiliano Zapata[94]

-

Colorized postcard of Zapata and his followers at Cuernavaca

-

Emiliano Zapata in 1915

Explanatory notes

editCitations

edit- ^ Centeno, Ramón I. (2018). "Zapata reactivado: Una visión žižekiana del Centenario de la Constitución". Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos. 34 (1): 36–62. doi:10.1525/msem.2018.34.1.36. S2CID 149383391.

- ^ Cisneros, Stefany (October 9, 2018). "¿Quién fue Emiliano Zapata? Conoce su biografía". México Desconocido. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020.

- ^ Knight 1986, p. 190.

- ^ ZAPATA ANTE LOS INDIOS: LA EXPEDICIÓN DE LOS MANIFIESTOS EN NÁHUATL Archived January 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kicza, John E. (1993). The Indian in Latin American History: Resistance, Resilience, and Acculturation. Scholarly Resources. p. 203. ISBN 978-0842024211.

- ^ Newell, Peter (1979). Zapata of Mexico. Sanday, Orkney, England: Cienfuegos Press. p. 176.

- ^ León-Portilla, Miguel (1978). Los manifiestos en Náhuatl de Emiliano Zapata. Mexico City: UNAM. p. 112.

- ^ Diccionario Porrúa de Historia, Biografía y Geografía de México. Editorial Porrúa.

- ^ Krauze 1997, p. 278.

- ^ a b Krauze 1997, p. 279.

- ^ Krauze 1997, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Krauze 1997, p. 277.

- ^ Miguel Leon-Portilla, Earl Shorris (2002). In the Language of Kings: An Anthology of Mesoamerican Literature, Pre-Columbian to the Present. W. W. Norton & Company. p. p. 374. ISBN 978-0393324075. (Testimony of Doña Luz Jiménez originally published in Horcasitas, 1968).

- ^ Hart, John Mason (1987). Revolutionary Mexico. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0520059955.

- ^ Knight 1986, p. 19.

- ^ a b Womack 1968, p. ?.

- ^ Meade 2016, p. 172.

- ^ "DeGolyer Library". Southern Methodist University. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- ^ "Emiliano Zapata: Life Before the Mexican Revolution". Latinamericanhistory.about.com. Archived from the original on December 28, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ Meade 2016, p. 166.

- ^ a b "The Mexican Revolution: Zapata, Diaz and Madero". Latinamericanhistory.about.com. May 13, 1911. Archived from the original on December 30, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Biography of Emiliano Zapata". Latinamericanhistory.about.com. April 10, 1919. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ quoted in Michael C. Meyer, Huerta: A Political Portrait. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1972, p. 22.

- ^ Womack 1968, p. 71.

- ^ quoted in Katz, Friedrich, The Secret War in Mexico, 260

- ^ El Hijo de Ahuizote, 31 de agosto de 1911, año 1, número 16, página 3,

- ^ a b c "Emiliano Zapata and the Plan of Ayala". Latinamericanhistory.about.com. April 10, 1919. Archived from the original on October 17, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ Meade 2016, p. 167.

- ^ a b c Womack 1968, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f Womack 1968.

- ^ Womack 1968, p. 78.

- ^ a b Womack 1968, p. 79.

- ^ Womack 1968, p. 80.

- ^ Womack 1968, p. 82.

- ^ Womack 1968, p. 186.

- ^ Womack 1968, p. 187.

- ^ Womack 1968, p. 188.

- ^ a b Meade 2016, p. 168.

- ^ Womack 1968, p. 190.

- ^ Attributed to Agustín Casasola, Mexico City, December 6, 1914. Gelatin dry-plate negative, 5x7 inches. Casasola Archive No. 5706.

- ^ Katz 1981, p. 259.

- ^ Katz 1981, p. 260.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 214–219.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 220–223.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 250–255.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 269–271.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 1983–1986.

- ^ Womack 1968, p. 311.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 313–314.

- ^ Womack 1968, p. 315.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 320–322.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Árbol Genealógico de Emiliano Zapata". slideserve (in Mexican Spanish). Archived from the original on April 19, 2023. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ "La hija del general Emiliano Zapata murió el domingo en Cuautla" (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: CNN Mexico. EFE. March 1, 2010. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- ^ Baltazar, Fernando (March 1, 2010). "Murió Ana María Zapata Portillo, última sobreviviente reconocida por El Caudillo" (in Spanish). Morelos, Mexico: La Jornada Morelos. Archived from the original on March 3, 2010. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- ^ Tonantzin, Pedro (April 22, 2014). "Carlota, última hija de Emiliano Zapata muere a los 100 años". Excelsior (in Mexican Spanish). Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ a b "Emiliano Zapata: ¿De dónde surge el rumor de su homosexualidad?". La Jornada (in Mexican Spanish). April 10, 2021. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Ulises, Edgar (October 23, 2020). "¿Emiliano Zapata era gay? Esto dicen los historiadores". homosensual (in Mexican Spanish). Archived from the original on August 30, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Ulises, Edgar (September 13, 2022). "Conoce a los personajes LGBT+ de la Revolución mexicana". homosensual (in Mexican Spanish). Archived from the original on September 24, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ a b "Manuel Palafox, el revolucionario más cercano a Emiliano Zapata". infobae (in Mexican Spanish). February 28, 2022. Archived from the original on May 4, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ "UNAM expone inédita carta de Emiliano Zapata". Fundación UNAM (in Mexican Spanish). December 2, 2019. Archived from the original on December 3, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ Santiago, Diego (December 10, 2019). "¿Era bisexual? Emiliano Zapata habría sido amante del yerno de Porfirio Díaz". RadioFormula (in Mexican Spanish). Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ Almazán, Yet Akatzin (September 6, 2022). "Manuel Palafox: "Ave negra" gay que encabezó la Revolución". homosensual (in Mexican Spanish). Archived from the original on September 18, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ "Manuel Palafox, "El Ave Negra": Homosexualidad en el Ejército Zapatista". Ulisex (in Mexican Spanish). May 9, 2020. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Katz 1981, p. 533.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Womack 1968, pp. 323–324.

- ^ Brunk 2008, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b Brunk 2008, p. 42.

- ^ a b Brunk 2008, p. 64.

- ^ Brunk 2008, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Brunk 2008, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Womack 1968, p. 328.

- ^ a b "Emiliano Zapata Facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Emiliano Zapata". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ "Lazaro Cardenas: Faces of the Revolution: The Storm That Swept Mexico". PBS. April 9, 1936. Archived from the original on January 8, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ "BRIA 25 4 Land Liberty and the Mexican Revolution". Constitutional Rights Foundation. Archived from the original on November 21, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ Brunk, Samuel (1996). ""The Sad Situation of Civilians and Soldiers": The Banditry of Zapatismo in the Mexican Revolution". The American Historical Review. doi:10.1086/ahr/101.2.331.

- ^ a b Knight 1986, p. 9.

- ^ "Mexican Money". Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016

- ^ a b Wolf, Eric R. (1958). "The Virgin of Guadalupe: A Mexican National Symbol". The Journal of American Folklore. 71 (279): 34–39. doi:10.2307/537957. JSTOR 537957.

- ^ Arnal, Ariel (December 7, 2015). "La devoción del salvaje. Religiosidad zapatista y silencio gráfico". L'Ordinaire des Amériques (in Spanish) (219). doi:10.4000/orda.2111. Archived from the original on January 20, 2022.

- ^ Hoffman, Matthew Cullinan. "The true story of For Greater Glory". Archived from the original on January 2, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023

- ^ Weis, Robert (2019). "Catholics and Anticlericals: From Reforma to Revolution". For Christ and Country: Militant Catholic Youth in Post-Revolutionary Mexico. Cambridge Latin American Studies. Cambridge Latin American Studies. pp. 9–26. doi:10.1017/9781108632492.002. ISBN 978-1108493024. S2CID 216613869.

- ^ Jrade, Ramon (1985). "Inquiries into the Cristero Insurrection against the Mexican Revolution". Latin American Research Review. 20 (2): 53–69. doi:10.1017/S0023879100034488. JSTOR 2503520. S2CID 133451500.

- ^ Posadas, Damariz (April 28, 2018). Maria Guadalupe and Liberation Theology: A Study of Two Religious Movements that have shaped Mexican culture and society (Thesis). Kenosha, Wisconsin: Carthage College. pp. 18–19.

- ^ Padilla, Tanalis (2008). Rural Resistance in the Land of Zapata: The Jaramillista Movement and the Myth of the Pax Priísta, 1940–1962. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 9780822343196.

- ^ Reynoso, Víctor-Hugo; Clark, James M. (June 15, 1998). "A dwarf sphenodontian from the Jurassic La Boca Formation of Tamaulipas, México". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (2): 333–339. Bibcode:1998JVPal..18..333R. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011061. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ "Mexico's naked Zapata painting causes protests". BBC News. December 11, 2019. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ Romo, Vanessa (December 11, 2019). "Nude, Pin-Up-Style Portrait Of Emiliano Zapata Sparks Protests In Mexico City". NPR.org. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ Small, Zachary (December 18, 2019). "Curator of Controversial 'Gay Zapata' Painting Decries 'Dangerous Precedent for Freedom of Expression'". ARTnews.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

Cited sources

edit- Brunk, Samuel (2008). The Posthumous Career of Emiliano Zapata. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292717800. OCLC 637001600.

- Katz, Friedrich (1981). The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226425886. OCLC 464429991.

- Knight, Alan (1986). The Mexican Revolution. Vol. 2. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803277717. OCLC 859937912.

- Krauze, Enrique (1997). Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0060929176. OCLC 1109152037.

- Meade, Teresa A. (2016) [2010]. "Revolution from Countryside to City: Mexico". History of Modern Latin America: 1800 to the Present (2nd ed.). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 161–179. ISBN 978-1118772485. OCLC 960231660.

- Rolls, Albert (2011). Emiliano Zapata: A Biography. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313380808. OCLC 701807906.

- Womack, John (1968). Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-0394708539. LCCN 68-23947. OCLC 229185765.

Further reading

edit- Brunk, Samuel, ¡Emiliano Zapata! Revolution and Betrayal in Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995.

- Caballero, Raymond. Lynching Pascual Orozco, Mexican Revolutionary Hero and Paradox. Create Space 2015. ISBN 978-1514382509

- Lucas, Jeffrey Kent. The Rightward Drift of Mexico's Former Revolutionaries: The Case of Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010.

- Mclynn, Frank. Villa and Zapata: A history of the Mexican Revolution. New York : Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2001.

- McNeely, John H. "Origins of the Zapata revolt in Morelos." Hispanic American Historical Review (1966): 153–169.

Historiography

edit- Golland, David Hamilton. "Recent Works on the Mexican Revolution." Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe 16.1 (2014). online

- McNamara, Patrick J. "Rewriting Zapata: Generational Conflict on the Eve of the Mexican Revolution." Mexican Studies-Estudios Mexicanos 30.1 (2014): 122–149.

In Spanish

edit- Horcasitas, Fernando. De Porfirio Díaz a Zapata, memoria náhuatl de Milpa Alta, UNAM, México DF. 1968 (eye and ear-witness account of Zapata speaking Nahuatl)

- Krauze, Enrique. Zapata: El amor a la tierra, in the Biographies of Power series.

External links

edit- Emiliano Zapata Quotes, Facts, Books and Movies Archived September 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Full text html version of Zapata's "Plan de Ayala" in Spanish

- Emiliano Zapata videos

- Bicentenario del inicio del movimiento de Independencia Nacional y del Centenario del inicio de la Revolución Mexicana

- Miguel Angel Mancera Espinosa

- "Emiliano Zapata", BBC Mundo.com