Stresemann's bushcrow (Zavattariornis stresemanni), also known as the Abyssinian pie, bush crow, Ethiopian bushcrow, or by its generic name Zavattariornis, is a rather starling-like bird, which is a member of the crow family, Corvidae. It is slightly larger than the North American blue jay and is a bluish-grey in overall colour which becomes almost white on the forehead. The throat and chest are creamy-white with the tail and wings a glossy black. The black feathers have a tendency to bleach to brown at their tips. The iris of the bird is brown and the eye is surrounded by a band of naked bright blue skin. The bill, legs, and feet are black.

| Stresemann's bushcrow | |

|---|---|

| |

| At Yabello Wildlife Sanctuary, Ethiopia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Zavattariornis Moltoni, 1938 |

| Species: | Z. stresemanni

|

| Binomial name | |

| Zavattariornis stresemanni Moltoni, 1938

| |

| |

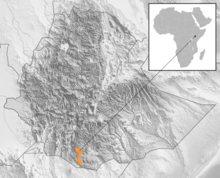

| Distribution map | |

Feeding is usually in small groups and the bird takes mainly insects. Breeding usually starts in March, with the birds building their nest high in an acacia tree. The birds usually lay five to six cream eggs with lilac blotches. The nest itself is globular in shape with a tubular entrance on top. It is possible that more than just the breeding pair visit the nest and that the young of previous years help in rearing the young.

The range of this species is quite restricted, it being confined to thorn acacia country in southern Ethiopia near Yavello (Javello), Mega, and Arero. It can be curiously absent from apparently suitable country near these areas; the reasons for this were formerly unclear, but are now thought to be related to the species requiring a "bubble" of lower temperature for proper foraging, which is only present within its small range, making it one of the few warm-blooded animals whose survival is wholly dependent on temperature (along with the sympatric white-tailed swallow). This requirement makes it extremely vulnerable to climate change, and massive declines and even potential extinction in the wild are projected in the future, making it one of the birds most threatened by climate change.[2]

Taxonomy

editStresemann's bushcrow was formally described in 1938 by the Italian ornithologist Edgardo Moltoni.[3] The species has been placed in several bird families since its description.[4] It has long been considered a member of the crow family Corvidae; however, several atypical features, such as its lice being from the suborder Mallophaga, its bare facial skin being capable of movement, and the structure of its palate, have suggested that it may belong in another family.[4] Some authors placed the species within the starling family Sturnidae due to the bushcrow's similarities in behavior and size with the wattled starling.[4] Other authors have placed it in its own monotypic family, Zavattariornithidae.[4] DNA-sequencing analysis supports its placement in the corvids, with its closest relatives being the ground jays, and the piapiac.[5] It has been suggested that the bushcrow is a surviving relict ancestor to several of these relatives.[6]

This species has numerous common names, including Stresemann's bushcrow, bush-crow, Ethiopian bushcrow, Abyssinian bushcrow, and Zavattariornis.[4]

The genus name Zavattariornis commemorates Edoardo Zavattari, an Italian zoologist and explorer who served as the director of Rome University's Zoological Institute between 1935 and 1958.[7] Its name commemorates Erwin Stresemann, a German ornithologist.[8]

Description

editThe Stresemann's bushcrow is about 28 centimeters (11 in) long and weighs 130 grams (4.6 oz).[4] The genders look similar and are not sexually dimorphic.[9] Overall it is pale grey with a black tail and wings.[4] The head, mantle, scapulars, back, rump, and uppertail coverts are all a pale grey.[4] The feathers on the forehead, upper ear-coverts, and throat fade into white.[4] The bright azure skin around the bushcrow's eye is featherless and can be inflated, narrowing the blackish-brown eye into a slit.[4][9] The feathers behind the eye are capable of moving to reveal an oblong pink patch of skin.[4] The bird's black beak decurves into a sharply pointed tip and is relatively small for a corvid.[4][9] This beak is 33 to 39 millimeters (1.3 to 1.5 in) long.[6] The feathers on the bird's chin are fine and can form a small tuft when erected.[4] The bushcrow's breast and flanks are pale grey, fading into white on the rear flanks, belly, and undertail.[9] On the wings, the lesser and median upper-wing coverts are grey, while the rest of the wing is a slightly glossy blue-black.[4][9] Its blue-black tail is relatively long and square-ended.[4] Its legs are black.[9] When the plumage becomes worn, the upperparts appear to have a brownish tinge.[6] The juvenile Stresemann's bushcrow is slightly duller than the adult, and the feathers of the body and upperwings are fringed with creamy-fawn.[9] The facial skin, bill, and legs are also a dull grey.[6]

The bushcrow is a very vocal species, particularly when foraging.[9] Its main contact call has been described as a single metallic "kej".[9] While flying, the species frequently calls out a nasal, rapid "kerr kerr kerr".[9] While these are the most frequent vocalizations, several others are known.[9] Allopreening adults utter a metallic "kaw, kaw, kaw".[9] Foraging birds call out "how, how, how", a single, quiet "quak", and a soft, repeated "guw".[9] While building its nest, the bushcrow is known to utter a low "keh" sound, and adults utter a deep "waw" while rubbing their bills together.[9]

Distribution and habitat

editThis species is endemic to central-southern Ethiopia.[10] It lives in a small area circumscribed by the towns of Yabelo, Borena, Mega, and Arero in Sidamo Province, and settles in wildlife under protection within Yabelo Wildlife Sanctuary and Borana National Park.[6] Its total range covers about 2,400 square kilometers (930 sq mi).[6]

The Stresemann's bushcrow lives in flat savanna covered with mature acacia and Commiphora thornbushes.[9] The bird prefers open short-grass savannas with scattered stands of these mature thornbushes.[9] The soil must be deep and rich to support the bushcrow.[9] It is most numerous when these stands are next to agricultural fields.[9] For many years it was unknown why the species could be completely absent from areas of suitable habitat near seemingly identical but inhabited land.[6] However recent research has revealed that the bird appears to inhabit an area with a very precise average temperature extreme, all of the seemingly suitable but uninhabited surrounding lands actually have a slightly higher average temperature that appears to prevent the birds from successfully colonizing.[11][12] It is also not found near the scattered broadleaf woodland made up of Combretum and Terminalia.[9] Its habitat is between 1,300 and 1,800 meters (4,300 and 5,900 ft) above sea level.[9]

Ecology and behavior

editThe Stresemann's bushcrow is normally found in groups of about six birds.[6] This species does not migrate.[9]

Diet

editThe bushcrow feeds both on the ground and in trees.[6] It begins foraging at sunrise.[9] While foraging, a bushcrow can be alone, in a pair, or in a group of six or seven other bushcrows.[9] A foraging bushcrow digs vigorously in the soil while its beak is held slightly open to catch any insects it unearths.[9] When it catches something, it carries it to the nearest tree or bush, pins it down with its foot, and kills and eats the prey.[9] This species has also been seen using its beak to tear apart rotten wood and inspecting cattle dung in the search for food.[9] It may also land on the backs of cattle to search for parasites.[9] It can also chase flying insects, which it does on foot, abruptly changing direction and taking flying leaps after its prey.[9] It often mixes with white-crowned starlings, red-billed hornbills, red-billed buffalo weavers, and superb starlings while foraging.[9] When hunting in the trees, it is capable of walking atop horizontal branches and jumping upwards towards the crown, then descending in a glide from the crown to the ground.[9]

It eats primarily invertebrates and specifically insects, including termites.[6] Larvae and pupae, especially of Coeloptera moths, are eaten as well as the adults.[9]

Reproduction

editThe Stresemann's bushcrow nests either alone or in a small, loosely connected colony of three to five nests.[9] It is monogamous and may form a lifelong pair bond.[9] The bushcrow occasionally has a third bird, or in rare cases two to four more, help the breeding couple both build the nest and care for the young.[9] The helpers may also not be restricted to helping one nest at a time, as they have been seen at nests across the loose colonies.[9] Allofeeding and allopreening, where the birds feed or preen each other, takes place both between the pair and with the other bushcrows in the colony.[9] The bushcrow lays its eggs shortly after the first rains, which normally occur in late February and early March, leading to its eggs being laid in late March and early April.[9]

The nest is an untidy globular structure, on which the roof tapers to a point that has an opening into the interior chamber.[6] The nest is 60 centimeters (24 in) in diameter while the interior chamber is 30 centimeters (12 in) across.[6] To start constructing the nest, a single twig is inserted into the top of an acacia tree 5 to 6 meters (16 to 20 ft) above the ground.[6] This leads to the paired bushcrows becoming excited, engorging their blue facial skin.[9] Almost ritualistically the pair then pick the acacia's leaves and twigs, dropping them to the ground.[9] The pair end this display by chasing each other through the trees before continuing construction.[9] The nest is made out of thorny twigs while the interior chamber is lined with dry grass and dried cattle dung.[6] Damp soil is used to keep the initial twigs connected.[9] Old nests are repaired and reused.[9]

Up to six eggs are laid in the nest.[6] The bushcrow's eggs are cream-colored with pale lilac blotches that concentrate into a ring at the wider end.[6]

Relationship with humans

editPrior to modern settlement in villages, the nomadic indigenous peoples of Ethiopia provided easy hunting grounds for the bushcrow as they left loose, dung-covered soil behind as they moved their cattle.[13] This provided a rich abundance of beetle larvae for the bushcrow to feed upon.[13]

Conservation

editChanges in the grazing habits of Ethiopia's indigenous peoples following the recent trend of settling in permanent villages have negatively impacted the Stresemann's bushcrow.[13] While previously grazers left the soil loose and covered in dung to support the bushcrow's prey, this new lifestyle has resulted in overgrazing and soil compaction in some areas.[13] The idea of private land ownership has also led to intensive planting of cash crops such as maize.[9] The rich soil that the species needs to forage is also prime farming land.[9] In the Yabello Wildlife Sanctuary, acacia trees are being collected for firewood, removing the bushcrow's nesting site.[13] While protected under law, this sanctuary has difficulties enforcing the law.[9] It is believed that between 1999 and 2003 the population of the bushcrow declined by 80%.[13]

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species lists the Stresemann's bushcrow as endangered because of its very restricted range and loss of suitable habitat. The population seems to be declining rapidly and in 2007 it was estimated that there might be fewer than 10,000 birds remaining. [1]

Climate change

editDue to its extremely unusual and specific temperature requirements, the Stresemann's bushcrow is considered one of the most threatened birds by climate change; climate change is predicted to reduced its range by 90% by 2070 in even the best-case scenarios (occupied range can often overestimate the number of individuals occupying the range, so the estimated population reduction may be even more than 90%), dramatically increasing the risk of extinction, with worse scenarios leading to total extinction in the wild. A similar outcome is predicted for the white-tailed swallow (Hirundo megaensis), which shares the same habitat and likely similar requirements, although the estimated range reduction is much lower for the swallow. Both species may be the only examples of warm-blooded animals whose range is fully driven by the climate. Intensive conservation such as captive breeding and assisted migration may be necessary to preserve the Stresemann's bushcrow. The birds and their projected decline may be used as indicator species for climate change, allowing them to test the reliability of habitat models for other threatened animals. Both may also serve as flagship species for the impacts of climate change on avian diversity in Africa.[2][14]

References

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International. (2016). "Zavattariornis stresemanni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22705877A94039369. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22705877A94039369.en. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ a b Bladon, Andrew J.; Donald, Paul F.; Collar, Nigel J.; Denge, Jarso; Dadacha, Galgalo; Wondafrash, Mengistu; Green, Rhys E. (2021-05-19). "Climatic change and extinction risk of two globally threatened Ethiopian endemic bird species". PLOS ONE. 16 (5): e0249633. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1649633B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0249633. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 8133463. PMID 34010302.

- ^ Moltoni, Edgardo (1938). "Zavattariornis stresemanni novum genus et nova species Corvidarum" (PDF). Ornithologische Monatsberichte (in Italian). 46: 80–83.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o dos Anjos et al. 2009, p. 608

- ^ McCullough, J.M.; Hruska, J.P.; Oliveros, C.H.; Moyle, R.G.; Andersen, M.J. (2023). "Ultraconserved elements support the elevation of a new avian family, Eurocephalidae, the white-crowned shrikes". Ornithology: ukad025. doi:10.1093/ornithology/ukad025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Madge & Burn 1994, p. 123

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 413. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Jones, Samuel. "Bush-crow diaries: The mystery of the Abyssinian Pie". Scientific American Blog Network.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as dos Anjos et al. 2009, p. 609

- ^ Madge & Burn 1994, p. 50

- ^ "Scientists discover an 'invisible barrier' that holds the answer to one of nature's little mysteries | BirdLife Community". Birdlife.org. 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ^ Bladon, A.J.; Donald, P.F.; Jones, S.E.I.; Collar, N.J.; Deng, J.; Dadacha, G.; Abebe, Y.D.; Green, R.E. (2019). "Behavioural thermoregulation and climatic range restriction in the globally threatened Ethiopian Bush‐crow Zavattariornis stresemanni". Ibis. 161 (3): 546–558. doi:10.1111/ibi.12660.

- ^ a b c d e f dos Anjos et al. 2009, p. 564

- ^ "Monitoring species condemned to extinction may help save others as global temperatures rise". phys.org. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

Cited texts

edit- dos Anjos, Luiz; Debus, Stephen; Madge, Steve; Marzluff, John (2009). "Family Corvidae (Crows)". In del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Christie, David (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 14. Bush-shrikes to Old World Sparrows. Barcelona: Lynx Editions. ISBN 978-84-96553-50-7.

- Fry, C. Hilary; Keith, Stuart; Urban, Emil K. (2000). The Birds of Africa Volume VI. London: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-137306-1.

- Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1994). Crows and Jays: A Guide to the Crows, Jays, and Magpies of the World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-67171-X.

Further reading

edit- Gedeon, Kai (2006) Observations on the biology of the Ethiopean Bush Crow Zavattariornis stresemanni Bulletin of the African Bird Club Vol 13 No 2 pages 178 - 188

External links

edit- Stresemann's bushcrow from the Internet Bird Collection

- Anthony Disley line drawing of Stresemann's bushcrow Archived 2003-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- BirdLife Species Factsheet