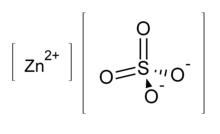

Zinc sulfate describes a family of inorganic compounds with the formula ZnSO4(H2O)x. All are colorless solids. The most common form includes water of crystallization as the heptahydrate,[4] with the formula ZnSO4·7H2O. As early as the 16th century it was prepared on the large scale, and was historically known as "white vitriol"[5] (the name was used, for example, in 1620s by the collective writing under the pseudonym of Basil Valentine)[citation needed]. Zinc sulfate and its hydrates are colourless solids.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Zinc sulfate

| |

| Other names

White vitriol

Goslarite | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.904 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

| UN number | 3077 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| ZnSO4 | |

| Molar mass | 161.44[1] g/mol (anhydrous) 179.47 g/mol (monohydrate) 287.53 g/mol (heptahydrate) |

| Appearance | white powder |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 3.54 g/cm3 (anhydrous) 2.072 g/cm3 (hexahydrate) |

| Melting point | 680 °C (1,256 °F; 953 K) decomposes (anhydrous) 100 °C (heptahydrate) 70 °C, decomposes (hexahydrate) |

| Boiling point | 740 °C (1,360 °F; 1,010 K) (anhydrous) 280 °C, decomposes (heptahydrate) |

| 57.7 g/100 mL, anhydrous (20 °C) (In aqueous solutions with a pH < 5)[2] | |

| Solubility | alcohols |

| −45.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.658 (anhydrous), 1.4357 (heptahydrate) |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

120 J·mol−1·K−1[3] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−983 kJ·mol−1[3] |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H302, H318, H410 | |

| P264, P270, P273, P280, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P310, P330, P391, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 1698 |

| Related compounds | |

Other cations

|

Cadmium sulfate Manganese sulfate |

Related compounds

|

Copper(II) sulfate |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Uses

editManufacturing

editThe main application of the heptahydrate is as a coagulant in the production of rayon. It is also a precursor to the pigment lithopone. It is also used as an electrolyte for zinc electroplating, as a mordant in dyeing, and as a preservative for skins and leather.

Nutrition

editZinc sulfate is used to supply zinc in animal feeds, fertilizers, toothpaste, and agricultural sprays. Zinc sulfate,[6] like many zinc compounds, can be used to control moss growth on roofs.[7]

Zinc sulfate can be used to supplement zinc in the brewing process. Zinc is a necessary nutrient for optimal yeast health and performance, although it is not a necessary supplement for low-gravity beers, as the grains commonly used in brewing already provide adequate zinc. It is a more common practice when pushing yeast to their limit by increasing alcohol content beyond their comfort zone. Before modern stainless steel, brew Kettles, fermenting vessels and after wood, zinc was slowly leached by the use of copper kettles. A modern copper immersion chiller is speculated to provide trace amounts of zinc; thus care must be taken when adding supplemental zinc so as not to cause excess. Side effects include "...increased acetaldehyde and fusel alcohol production due to high yeast growth when zinc concentrations exceed 5 ppm. Excess zinc can also cause soapy or goaty flavors."[8][9][10]

Zinc sulfate is a potent inhibitor of sweetness perception for most sweet-tasting substances.[11]

Medicine

editIt is used as a dietary supplement to treat zinc deficiency and to prevent the condition in those at high risk.[12] Side effects of excess supplementation may include abdominal pain, vomiting, headache, and tiredness.[13] it is also used together with oral rehydration therapy (ORT) and an astringent.[4]

Production, reactions, structure

editZinc sulfate is produced by treating virtually any zinc-containing material (metal, minerals, oxides) with sulfuric acid.[4]

Specific reactions include the reaction of the metal with aqueous sulfuric acid:

- Zn + H2SO4 + 7 H2O → ZnSO4·7H2O + H2

Pharmaceutical-grade zinc sulfate is produced by treating high-purity zinc oxide with sulfuric acid:

- ZnO + H2SO4 + 6 H2O → ZnSO4·7H2O

In aqueous solution, all forms of zinc sulfate behave identically. These aqueous solutions consist of the metal aquo complex [Zn(H2O)6]2+ and SO2−

4 ions. Barium sulfate forms when these solutions are treated with solutions of barium ions:

- ZnSO4 + BaCl2 → BaSO4 + ZnCl2

With a reduction potential of −0.76 V, zinc(II) reduces only with difficulty.

When heated above 680 °C, zinc sulfate decomposes into sulfur dioxide gas and zinc oxide fume, both of which are hazardous.[14]

The heptahydrate is isostructural with ferrous sulfate heptahydrate. The solid consists of [Zn(H2O)6]2+ ions interacting with sulfate and one water of crystallization by hydrogen bonds. Anhydrous zinc sulfate is isomorphous with anhydrous copper(II) sulfate. It exists as the mineral zincosite.[15] A monohydrate is known.[16] The hexahydrate is also recognized.[17]

Minerals

editAs a mineral, ZnSO4•7H2O is known as goslarite. Zinc sulfate occurs as several other minor minerals, such as zincmelanterite, (Zn,Cu,Fe)SO4·7H2O (structurally different from goslarite). Lower hydrates of zinc sulfate are rarely found in nature: (Zn,Fe)SO4·6H2O (bianchite), (Zn,Mg)SO4·4H2O (boyleite), and (Zn,Mn)SO4·H2O (gunningite).

Safety

editZinc sulfate powder is an eye irritant. Ingestion of trace amounts is considered safe, and zinc sulfate is added to animal feed as a source of essential zinc, at rates of up to several hundred milligrams per kilogram of feed. Excess ingestion results in acute stomach distress, with nausea and vomiting appearing at 2–8 mg/kg of body weight.[18] Nasal irrigation with a solution of zinc sulfate has been found to be able to damage the olfactory sense nerves and induce anosmia in a number of different species, including humans.[19]

References

edit- ^ "Zinc sulphate".

- ^ Lide, David R., ed. (2006). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0487-3.

- ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A23. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ a b c Dieter M. M. Rohe; Hans Uwe Wolf (2005). "Zinc Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/14356007.a28_537. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Roscoe, Henry Enfield; Schorlemmer, Carl (1889). A Treatise on Chemistry: Metals. Appleton.

- ^ "Zinc Sulphate". Chemical & Fertilizer Expert. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ "Moss on Roofs" (PDF). Community Horticultural Fact Sheet #97. Washington State University King County Extension. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015.

- ^ "Metallurgy for Homebrewers". Brew Your Own Magazine.

- ^ "The Effect of Zinc on Fermentation Performance". Braukaiser blog.

- ^ Šillerová, Silvia; Lavová, Blažena; Urminská, Dana; Poláková, Anežka; Vollmannová, Alena; Harangozo, Ľuboš (February 2012). "Preparation of Zinc Enriched Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) by Cultivation With Different Zinc Salts". Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Food Sciences. 1 (Special issue): 689–695. ISSN 1338-5178.

- ^ Keast, R. S.J.; Canty, T. M.; Breslin, P. A. (2004). "Oral Zinc Sulfate Solutions Inhibit Sweet Taste Perception". Chemical Senses. 29 (6): 513–521. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjh053. PMID 15269123.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 700. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ^ World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 351. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ "Zinc Sulphate Zinc Sulfate MSDS Sheet of Manufacturers". Mubychem.com. 5 May 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ Wildner, M.; Giester, G. (1988). "Crystal Structure refinements of synthetic chalcocyanite (CUSO4) and zincosite (ZnSO4)". Mineralogy and Petrology. 39 (3–4): 201–209. Bibcode:1988MinPe..39..201W. doi:10.1007/BF01163035. S2CID 93701665.

- ^ Wildner, M.; Giester, G. (1991). "The Crystal Structures of Kieserite-Type Compounds. I. Crystal Structures of Me(II)SO4*H2O (Me = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn)". Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie - Monatshefte. 1991: 296–306.

- ^ Spiess, M.; Gruehn, R. (1979). "Beiträge zum thermischen Verhalten von Sulfaten. II. Zur thermischen Dehydratisierung des ZnSO4•7H2O und zum Hochtemperaturverhalten von wasserfreiem ZnSO4". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie. 456: 222–240. doi:10.1002/zaac.19794560124.

- ^ "Scientific Opinion on safety and efficacy of zinc compounds (E6) as feed additives for all animal species: Zinc sulphate monohydrate". EFSA Journal. 10 (2). European Food Safety Authority (EFSA): 2572. February 2012. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2572.

- ^ Davidson, Terence M.; Smith, Wendy M. (19 July 2010). "The Bradford Hill Criteria and Zinc-Induced Anosmia: A Causality Analysis". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 136 (7): 673–676. doi:10.1001/archoto.2010.111. PMID 20644061.