This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2016) |

The facet joints (also zygapophysial joints, zygapophyseal, apophyseal, or Z-joints) are a set of synovial, plane joints between the articular processes of two adjacent vertebrae. There are two facet joints in each spinal motion segment and each facet joint is innervated by the recurrent meningeal nerves.

| Facet joint | |

|---|---|

A thoracic vertebra. The facet joint is the joint between the inferior articular process (labeled at bottom) and the superior articular process (labeled at top) of the subsequent vertebra. | |

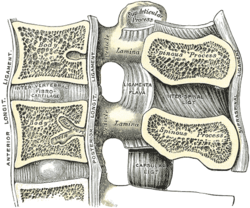

Median sagittal section of two lumbar vertebrae and their ligaments | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | articulationes zygapophysiales |

| MeSH | D021801 |

| TA98 | A03.2.06.001 |

| TA2 | 1707 |

| FMA | 10447 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Innervation

editInnervation to the facet joints vary between segments of the spinal, but they are generally innervated by medial branch nerves that come off the dorsal rami. It is thought that these nerves are for primary sensory input, though there is some evidence that they have some motor input local musculature. Within the cervical spine, most joints are innervated by the medial branch nerve (a branch of the dorsal rami) from the same levels. In other words, the facet joint between C4 and C5 vertebral segments is innervated by the C4 and C5 medial branch nerves. However, there are two exceptions:

- The facet joint between C2 and C3 is innervated by the third occipital nerve and the C3 medial branch nerve.

- The facet joint between C7 and T1 is innervated by the C7 and C8 medial branch nerves.[citation needed]

In the thoracic and lumbar spine, the facet joints are innervated by the medial branch nerves from the vertebral segment above the upper segment and the upper segment. For example, the facet joint between T1 and T2 is innervated by C8 and T1 medial branch nerves. Facet joint between L1 and L2; the T12 and L1 medial branch nerves. However, the L5 and S1 facet joint is innervated by the L4 medial branch nerve and the L5 dorsal ramus. In this case, there is no L5 medial branch to innervate the facet joint.[citation needed]

Function

editThe biomechanical function of each pair of facet joints is to guide and limit movement of the spinal motion segment.[1][2] In the lumbar spine, for example, the facet joints function to protect the motion segment from anterior shear forces, excessive rotation and flexion. Facet joints appear to have little influence on the range of side bending (lateral flexion). These functions can be disrupted by degeneration, dislocation, fracture, injury, instability from trauma, osteoarthritis, and surgery. In the thoracic spine the facet joints function to restrain the amount of flexion and anterior translation of the corresponding vertebral segment and function to facilitate rotation. Cavitation of the synovial fluid within the facet joints is responsible for the popping sound (crepitus) associated with manual spinal manipulation, commonly referred to as "cracking the back."

The facet joints, both superior and inferior, are aligned in a way to allow flexion and extension, and to limit rotation. This is especially true in the lumbar spine.

Facet joint arthritis

editIn large part due to the mechanical nature of their function, all joints undergo degenerative changes with the wear and tear of age. This is particularly true for joints in the spine, and the facet joint in particular. This is commonly known as facet joint arthritis or facet arthropathy.[3] As with any arthritis, the joint can become enlarged due to the degenerative process. Even small changes to the facet joint can narrow the intervertebral foramen, possibly impinging on the spinal nerve roots within.[3] More advanced cases can involve severe inflammatory responses in the Z-joint, not unlike a swollen arthritic knee.

Diagnosis

editFacet joint arthritis may not always have any symptoms, but often manifests as a dull ache across the back.[4] However like many deep organs of the body it can be experienced by the patient in a variety of referral pain patterns. The location of facet joints, deep in the back and covered with large tracts of paraspinal muscles, further complicate the diagnostic approach. Typically facet joint arthritis is diagnosed with specialized physical examination by specialist physicians such as facet loading (also called Kemps test). However, this test has poor sensitivity (50-70%) [5] and specificity (67.3%) [6] for lumbar facet pain. Often providers perform diagnostic injections to determine if the facet joint is the underlying source of pain.

Treatment

editConservative treatment

editConservative treatment of facet joint arthritis involves physical therapy or osteopathic medicine, with muscle strengthening, correction of posture, and biomechanics being the key.[citation needed]

Corticosteroid injections

editCorticosteroid injections into the joint space may provide temporary pain relief anywhere from days to several months. With repeated injections, sometimes the patient may experience a more permanent improvement in their symptoms.[7] Steroid injections are typically performed under image guidance to ensure accuracy given the complex shape and deep location of the facet.[8] Some patients do not benefit from corticosteriod injections.[7]

Ablation

editRadiofrequency ablation or lesioning, also known as rhizolysis, can be used to give longer lasting relief by destroying the nerves that supply the facet joint (medial branch nerves).[9] Current guidelines as per the International Spine Intervention Society require two successful medial branch blocks before progressing to a radiofrequency ablation.

Surgery

editSurgery, in the form of a facetectomy, can be performed in certain cases, particularly when the nerve root is affected.

Etymology

editAncient Greek: zygon ("yoke") + apo ("out/from") + phyein ("grow")

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Lowe, Whitney; Chaitow, Leon (2009-01-01), Lowe, Whitney; Chaitow, Leon (eds.), "Chapter 9 - Lumbar and thoracic spine", Orthopedic Massage (Second Edition), Edinburgh: Mosby, pp. 175–198, doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-06812-6.00009-x, ISBN 978-0-443-06812-6, retrieved 2020-11-03

- ^ Lowe, Whitney (2003-01-01), Lowe, Whitney (ed.), "Chapter 9 - Lumbar and thoracic spine", Orthopedic Massage, Edinburgh: Mosby, pp. 129–143, doi:10.1016/b978-072343226-5.50014-9, ISBN 978-0-7234-3226-5, retrieved 2020-11-03

- ^ a b Mann, S. J.; Viswanath, O.; Singh, P. (2022). "Lumbar Facet Arthropathy". StatPearls. StatPearls. PMID 30855816.

- ^ Hou, David D.; Carrino, John A. (2007-01-01), Waldman, Steven D.; Bloch, Joseph I. (eds.), "chapter 8 - Nuclear Medicine Techniques", Pain Management, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 85–92, doi:10.1016/b978-0-7216-0334-6.50012-1, ISBN 978-0-7216-0334-6, retrieved 2020-11-03

- ^ "Relationship of Physical Examination Findings and Self-Reported Symptom Severity and Physical Function in Patients With Degenerative Lumbar Conditions". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ Manchikanti, L.; Pampati, V.; Fellows, B.; Baha, A. G. (April 2000). "The inability of the clinical picture to characterize pain from facet joints". Pain Physician. 3 (2): 158–166. doi:10.36076/ppj.2000/3/158. ISSN 1533-3159. PMID 16906195.

- ^ a b Lavelle, William F.; Carl, Allen L.; Lavelle, Elizabeth Demers; Furdyna, Aimee (2009-01-01), Smith, HOWARD S. (ed.), "Chapter 22 - BACK PAIN", Current Therapy in Pain, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 167–176, doi:10.1016/b978-1-4160-4836-7.00022-5, ISBN 978-1-4160-4836-7, retrieved 2020-11-03

- ^ NASS on facet joint injections

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-04-06. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

9. Shin-Tsu Chang, Chuan-Ching Liu, Wan-Hua Yang. Single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (hybrid imaging) in the diagnosis of unilateral facet joint arthritis after internal fixation for atlas fracture. HSOA Journal of Medicine: Study & Research 2019; 2: 010.

10. Zhu Wei Lim, Shih-Chuan Tsai, Yi-Ching Lin, Yuan-Yang Cheng, Shin-Tsu Chang. A worthwhile measurement of early vigilance and therapeutic monitor in axial spondyloarthritis: a literature review of quantitative sacroiliac scintigraphy. European Medical Journal (EMJ) Rheumatology 2021 July 15; 8[1]:129-139.