Journey to the West (Chinese: 西遊記; pinyin: Xīyóu Jì) is a Chinese novel published in the 16th century during the Ming dynasty and attributed to Wu Cheng'en. It is regarded as one of the great Chinese novels, and has been described as arguably the most popular literary work in East Asia.[2] It is widely known in English-speaking countries through Arthur Waley's 1942 abridged translation, Monkey.

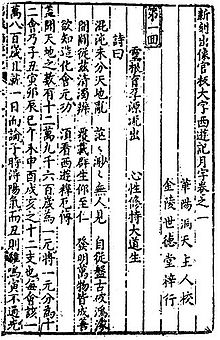

Earliest known edition of the book, published by the Shidetang Hall of Jinling, from the 16th century | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Author | Wu Cheng'en | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original title | 西遊記 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Language | Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Genre | Gods and demons fiction, Chinese mythology, fantasy, adventure | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Set in | Tang dynasty, 7th century AD | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Publication date | c. 1592 (print)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Publication place | Ming China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Published in English | 1942 (abridged) 1977–1983 (complete) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 895.1346 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Original text | 西遊記 at Chinese Wikisource | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 西遊記 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 西游记 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Record of the Western Journey" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Tây du kí | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 서유기 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 西遊記 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | さいゆうき | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The novel is a fictionalized and fantastic account of the pilgrimage of the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang, who journeyed to India in the 7th century AD to seek out and collect Buddhist scriptures (sūtras).[3] The novel retains the broad outline of Xuanzang's own account, Great Tang Records on the Western Regions, but embellishes it with fantasy elements from folk tales and the author's invention. In the story, the Buddha tasks the monk Tang Sanzang (or "Tripitaka"), with journeying to India and provides him with three protectors who agree to help him in order to atone for their sins: Sun Wukong (the "Monkey King"), Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing. Riding a White Dragon Horse, the monk and his three protectors journey to a mythical version of India and enlightenment through the power and virtue of cooperation.

Journey to the West has strong roots in Chinese folk religion, Chinese mythology, Chinese Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoist and Buddhist folklore, and the pantheon of Taoist immortals and Buddhist bodhisattvas are still reflective of certain Chinese religious attitudes today, while being the inspiration of many modern manhwa, manhua, manga and anime series. Enduringly popular,[4] the novel is at once a comic adventure story, a humorous satire of Chinese bureaucracy, a source of spiritual insight, and an extended allegory.

History

editCreation and authorship

editThe modern 100-chapter form of Journey to the West dates from the 16th century.[6] Embellished stories based on Xuanzang's journey to India had circulated through oral storytelling for centuries. They appeared in book form as early as the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279).[6] The Yongle Encyclopedia, completed in 1408, contains excerpts of a version of the story written in colloquial Chinese, and a Korean book from 1423 also includes a fragment of that story.[6] The earliest surviving edition of Journey to the West was published in Nanjing in 1592. Two earlier editions were published between 1522 and 1566, but no copies of them survived.[6][7]

The authorship of Journey to the West is traditionally ascribed to Wu Cheng'en, but the question is complicated by the fact that much of the novel's material originated from folk tales.[8][9] Anthony C. Yu, writing in 2012, warned that "this vexing dispute over the novel's authorship, similar to that on the priority of its textual versions, see-sawed back and forth for nearly a century without resolution."[10]

Hu Shih, literary scholar, former Chancellor of Peking University, and then Ambassador to the United States, wrote in 1942 that the novel was thought to have been written and published anonymously by Wu Cheng'en. He reasoned that the people of Wu's hometown attributed it to him early on, and kept records to that effect as early as 1625; thus, claimed Hu, Journey to the West was one of the earliest Chinese novels for which the authorship is officially documented.[11]

More recent scholarship casts doubts on this attribution. Brown University Chinese literature scholar David Lattimore stated in 1983: "The Ambassador's confidence was quite unjustified. What the gazetteer says is that Wu wrote something called The Journey to the West. It mentions nothing about a novel. The work in question could have been any version of our story, or something else entirely."[12] Translator W. J. F. Jenner pointed out that although Wu had knowledge of Chinese bureaucracy and politics, the novel itself does not include any political details that "a fairly well-read commoner could not have known."[8]

One interpretive tradition views Journey to the West as the outcome of a writing game which was popular among Chinese literati.[13]: 157

The overall plot of Journey to the West was "already a part of Chinese folk and literary tradition in the form of "folk stories with informal language", a poetic novelette, and a six-part drama play series, which was transcribed and written down, before the current version was written.[9] Fragments of an earlier text, Journey to the West as Storytelling, are recorded in other texts.[13]: 159 The narrative threads from this earlier text which survive are the wager between the Dragon King of the Jing River and fortune teller Yuan Shoucheng and the contest between the pilgrims and the three Taoist demons in Cart Slow Kingdom.[13]: 159

Regardless of the origins and authorship, Journey to the West has become the authoritative version of these folk stories,[8] and while the cumulative authorship of the text is acknowledged, Wu is generally accepted as the author of the 1592 printed version widely considered canonical.[13]: 158

Historical basis

editAlthough Journey to the West is a work of fantasy, it is based on the actual journey of the Chinese monk Xuanzang (602–664), who traveled to India in the 7th century in order to seek out Buddhist scriptures and bring them back to China. Xuanzang was a monk at Jingtu Temple in the imperial capital Chang'an (present-day Xi'an) during the late Sui dynasty and early Tang dynasty. He left Chang'an in 629, in defiance of Emperor Taizong of Tang's ban on travel. Helped by sympathetic Buddhists, Xuanzang traveled via Gansu and Qinghai to Kumul (Hami), thence following the Tian Shan mountains to Turpan. He then crossed regions that are today Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, into Gandhara, in what is today northern Pakistan, in 630. Xuanzang traveled throughout India for the next thirteen years, visiting important Buddhist pilgrimage sites, studying at the ancient university at Nalanda, and debating the rivals of Buddhism.

Xuanzang left India in 643 and arrived back in Chang'an in 646. Although he had defied the imperial travel ban when he left, Xuanzang received a warm welcome from Emperor Taizong upon his return. The emperor provided money and support for Xuanzang's projects. He joined Da Ci'en Monastery (Monastery of Great Maternal Grace), where he led the building of the Big Wild Goose Pagoda to store the scriptures and icons he had brought back from India. He recorded his journey in the book Great Tang Records on the Western Regions. With the support of the emperor, he established an institute at Yuhua Gong (Palace of the Luster of Jade) monastery dedicated to translating the scriptures he had brought back. His translation and commentary work established him as the founder of the Dharma character school of Buddhism. Xuanzang died on 7 March 664. The Xingjiao Monastery was established in 669 to house his ashes.

Synopsis

editThe novel has 100 chapters that can be divided into four unequal parts.

First Part

editThe first part, which includes chapters 1–7, is a self-contained introduction to the main story. It deals entirely with the earlier exploits of Sun Wukong, a monkey born from a stone nourished by the Five Elements, who learns the art of the Tao, 72 polymorphic transformations, combat, and secrets of immortality, and whose guile and force earns him the name Qitian Dasheng (simplified Chinese: 齐天大圣; traditional Chinese: 齊天大聖), or "Great Sage Equal to Heaven." His powers grow to match the forces of all of the Eastern (Taoist) deities, and the prologue culminates in Sun's rebellion against Heaven, during a time when he garnered a post in the celestial bureaucracy. Hubris proves his downfall when the Buddha manages to trap him under a mountain, sealing it with a talisman for five hundred years.

Second Part

editThe second part (chapters 8–12) introduces Tang Sanzang through his early biography and the background to his great journey. Dismayed that "the land of the South (i.e. Tang China) knows only greed, hedonism, promiscuity, and sins," the Buddha instructs the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara (Guanyin) to search China for someone to take the Buddhist sutras of "transcendence and persuasion for good will" back. Part of this section also relates to how Tang Sanzang becomes a monk (as well as revealing his past life as a disciple of the Buddha named "Golden Cicada" (金蟬子 Jīn Chánzi) and comes about being sent on this pilgrimage by Emperor Taizong, who previously escaped death with the help of an official in the Underworld. In the story, Tang Sanzang is considered an allegorical representation of the human heart.

Third Part

editThe third and longest section of the work is chapters 13–99, an episodic adventure story in which Tang Sanzang sets out to bring back Buddhist scriptures from Leiyin Temple on Vulture Peak in India, but encounters various evils along the way. The section is set in the sparsely populated lands along the Silk Road between China and India. The geography described in the book is, however, almost entirely fantasy; once Tang Sanzang departs Chang'an, the Tang capital, and crosses the frontier (somewhere in Gansu province), he finds himself in a wilderness of deep gorges and tall mountains, inhabited by demons and animal spirits who regard him as a potential meal (since his flesh was believed to give immortality to whoever ate it), with the occasional hidden monastery or royal city-state amidst the harsh setting.

Episodes consist of 1–4 chapters and usually involve Tang Sanzang being captured and having his life threatened while his disciples try to find an ingenious (and often violent) way of liberating him. Although some of Tang Sanzang's predicaments are political and involve ordinary human beings, they more frequently consist of run-ins with various demons, many of whom turn out to be earthly manifestations of heavenly beings (whose sins will be negated by eating the flesh of Tang Sanzang) or animal-spirits with enough Taoist spiritual merit to assume semi-human forms.

Chapters 13–22 do not follow this structure precisely, as they introduce Tang Sanzang's disciples, who, inspired or goaded by Guanyin, meet and agree to serve him along the way in order to atone for their sins in their past lives.

- The first is Sun Wukong, or the Monkey King (or just "Monkey"), whose given name loosely means "Monkey Awakened to Emptiness (Śūnyatā)", trapped under a mountain by the Buddha for defying Heaven. He appears right away in chapter 13. The most intelligent, the most powerful, and the most violent of the disciples, he is constantly reproved for his violence by Tang Sanzang. Ultimately, he can only be controlled by a magic gold ring that Guanyin has placed around his head, which causes him unbearable headaches when Tang Sanzang chants the Ring Tightening Mantra. In the story, Sun Wukong is an allegorical representation of the human mind and thought and impulse, and is often nicknamed the "Monkey mind".

- The second, appearing in chapter 19, is Zhu Wuneng / Zhu Bajie, literally "Pig Awakened to Ability" and "Eight Precepts Pig," sometimes translated as Pigsy or just Pig. He was previously the Marshal of the Heavenly Canopy, a commander of Heaven's naval forces, and was banished to the mortal realm for harassing the moon goddess Chang'e. A reliable fighter, he is characterized by his insatiable appetites for food and women, and is constantly looking for a way out of his duties, which causes significant conflict with Sun Wukong. In the story, Zhu Bajie is an allegorical representation of base human nature (or the Id).

- The third, appearing in chapter 22, is the river ogre Sha Wujing (literally "Sand Awakened to Purity"), also known as Friar Sand or Sandy. He was previously the celestial Curtain Lifting General, and was banished to the mortal realm for dropping (and shattering) a crystal goblet of the Queen Mother of the West. He is a quiet but generally dependable and hard-working character, who serves as the straight foil to the comic relief of Sun and Zhu. In the story, Sha Wujing is an allegorical representation of human obedience and conformity without thought.

- The fourth is Bai Long Ma (literally "White Dragon Horse"), the third son of the Dragon King of the West Sea, who was sentenced to death for setting fire to his father's great pearl. He was saved by Guanyin from execution to stay and wait for his call of duty. He has almost no speaking role, as throughout the story he mainly appears as a horse that Tang Sanzang rides on. In the story, the White Dragon Horse is an allegorical representation of the human will.

Chapter 22, where Sha Wujing is introduced, also provides a geographical boundary, as the river that the travelers cross brings them into a new "continent." Chapters 23–86 take place in the wilderness, and consist of 24 episodes of varying length, each characterized by a different magical monster or evil magician. There are impassibly wide rivers, flaming mountains, a kingdom with an all-female population, a lair of seductive spider spirits, and many other scenarios. Throughout the journey, the four disciples have to fend off attacks on their master and teacher Tang Sanzang from various monsters and calamities.

It is strongly suggested that most of these calamities are engineered by fate and/or the Buddha, as, while the monsters who attack are vast in power and many in number, no real harm ever comes to the four travelers. Some of the monsters turn out to be escaped celestial beasts belonging to bodhisattvas or Taoist sages and deities. Towards the end of the book, there is a scene where the Buddha commands the fulfillment of the last disaster, because Tang Sanzang is one short of the 81 tribulations required before attaining Buddhahood.

In chapter 87, Tang Sanzang finally reaches the borderlands of India, and chapters 87–99 present magical adventures in a somewhat more mundane setting. At length, after a pilgrimage said to have taken fourteen years (the text actually only provides evidence for nine of those years, but presumably there was room to add additional episodes) they arrive at the half-real, half-legendary destination of Vulture Peak, where, in a scene simultaneously mystical and comic, Tang Sanzang receives the scriptures from the living Buddha.

Fourth part

editChapter 100, the final chapter, quickly describes the return journey to the Tang Empire, and the aftermath in which each traveller receives a reward in the form of posts in the bureaucracy of the heavens. Sun Wukong and Tang Sanzang both achieve Buddhahood, Sha Wujing becomes an arhat, Bai Long Ma is made a nāga and Zhu Bajie, whose good deeds have always been tempered by his greed, is promoted to an altar cleanser (i.e. eater of excess offerings at altars).

Characters

editSun Wukong / Monkey King

editSun Wukong (孫悟空) (pinyin: sūnwùkōng) is the name given to this character by his teacher, Subhuti, the latter part of which means "Awakened to Emptiness" (in the Waley translation, Aware-of-Vacuity); he is often called the "Monkey King". He is born on Flower Fruit Mountain from a stone egg that forms from an ancient rock created by the coupling of Heaven and Earth. He first distinguishes himself by bravely entering the Water Curtain Cave on the mountain; for this feat, his monkey tribe gives him the title of "Handsome Monkey King (美猴王, měi hóuwáng)." After seeing a fellow monkey die because of old age, he decides to travel around the world to seek the Tao, and find a way to be able to live forever. He eventually found the "Grand Master of Bodhi (菩提祖師, pútí zǔshī)," who taught him the 72 heavenly methods of transformation and a "somersault cloud" which allows him to travel 108,000 li almost instantaneously. After angering several gods and coming to the attention of the Jade Emperor, he is given a minor position in heaven as the Keeper of Horses (弼馬溫, bìmǎwēn) so they can keep an eye on him. When Sun realizes that he was given the lowest position in heaven and is not considered a full-fledged god, he becomes very angry. Upon returning to his mountain, he puts up a flag and declares himself the "Great Sage Equal to Heaven (齊天大聖, qí tiān dàshèng)." The Jade Emperor dispatches celestial soldiers to arrest Sun Wukong, but none succeed. The Jade Emperor has no choice but to appoint him to be the guardian of the heavenly peach garden. The different varieties of peach trees in the garden bear fruit every 3,000, 6,000, and 9,000 years, and eating their flesh will bestow immortality and other gifts, so Sun Wukong eats nearly all of the ripe peaches. Later, after fairies who come to collect peaches for Xi Wangmu's heavenly peach banquet inform Sun Wukong he is not invited and make fun of him, he once again begins to cause trouble in Heaven, stealing heavenly wine from the peach banquet and eating Laozi's pills of immortality. He defeats an army of 100,000 celestial troops, led by the Four Heavenly Kings, Erlang Shen, and Nezha. Eventually, the Jade Emperor appeals to the Buddha, who seals Wukong under a mountain called Five Elements Mountain after the latter loses a bet regarding whether he can leap out of the Buddha's hand in a single somersault. Sun Wukong is kept under the mountain for 500 years and cannot escape because of a seal that was placed on the mountain. He is later set free when Tang Sanzang comes upon him during his pilgrimage and accepts him as a disciple.

His primary weapon is his staff, the "Ruyi Jingu Bang," which he can shrink down to the size of a needle and keep in his ear, as well as expand it to gigantic proportions. The rod, which weighs 17,550 pounds (7,960 kg), was originally a pillar supporting the undersea palace of the Dragon King of the East Sea, but he was able to pull it out of its support and can swing it with ease. The Dragon King had told Sun Wukong he could have the staff if he could lift it, but was angry when the monkey was actually able to pull it out and accused him of being a thief. Sun Wukong was insulted, so he demanded a suit of armor and refused to leave until he received one. The Dragon King of the East and the other dragon kings, fearful of Sun wreaking havoc in their domain, gave him a suit of golden armor. These gifts, combined with his devouring of the peaches of immortality, erasing his name from the Book of the Dead, drinking heavenly wine from the Peach Festival, eating Laozi's pills of immortality, and being tempered in Laozi's Eight-Trigram Furnace (after which he gained a steel-hard body and fiery golden eyes that could see far into the distance and through any disguise), makes Sun Wukong by far the strongest member of the pilgrimage. Besides these abilities, he can also pluck hairs from his body and blow on them to convert them into whatever he wishes (usually clones of himself to gain a numerical advantage in battle). Furthermore, he is a master of the 72 methods of transformation (七十二变),[a] and can transform into anything that exists (animate and inanimate).[a] Notably, however, Sun cannot fight as well underwater, and often the pilgrimage must rely on Pigsy and Sandy for marine combat. The monkey, nimble and quick-witted, uses these skills to defeat all but the most powerful of demons on the journey.

Sun's behavior is checked by a band placed around his head by Guanyin, which cannot be removed by Sun Wukong himself until the journey's end. Tang Sanzang can tighten this band by chanting the "Ring Tightening Mantra" (taught to him by Guanyin) whenever he needs to chastise him. The spell is referred to by Tang Sanzang's disciples as the "Headache Sutra". Tang Sanzang speaks this mantra quickly in repetition when Sun disobeys him.

Sun Wukong's childlike playfulness and often goofy impulsiveness is in contrast to his cunning mind. This, coupled with his great power, makes him a trickster hero. His antics present a lighter side in the long and dangerous trip into the unknown.

After completion of the journey, Sun is granted the title of Victorious Fighting Buddha (斗战胜佛; 鬥戰勝佛; dòu zhànshèng fó) and ascends to Buddhahood.

Tang Sanzang / Tripitaka

editThe monk Tang Sanzang (唐三藏, meaning "Tripitaka Master of Tang," with Tang referring to the Tang dynasty and Sanzang referring to the Tripiṭaka, the main categories of texts in the Buddhist canon which is also used as an honorific for some Buddhist monks) is a Buddhist monk who had renounced his family to become a monk from childhood. He is just called "Tripitaka" in many English versions of the story. He set off for Tianzhu Kingdom (天竺国, an appellation for India in ancient China) to retrieve original Buddhist scriptures for China. Although he is helpless in defending himself, the bodhisattva Guanyin, helps by finding him powerful disciples who aid and protect him on his journey. In return, the disciples will receive enlightenment and forgiveness for their sins once the journey is done. Along the way, they help the local inhabitants by defeating various monsters and demons who try to obtain immortality by consuming Tang Sanzang's flesh.

Zhu Bajie / Pigsy

editZhu Bajie (豬八戒, literally "Pig of the Eight Prohibitions") is also known as Zhu Wuneng ("Pig Awakened to Power"), and given the name "Monk Pig", "Piggy", "Pigsy", or just simply "Pig" in English.

Once an immortal who was the Marshal of the Heavenly Canopy commanding 100,000 naval soldiers of the Milky Way, he drank too much during a celebration of the gods and attempted to harass the moon goddess Chang'e, resulting in his banishment to the mortal world. He was supposed to be reborn as a human but ended up in the womb of a sow due to an error on the Reincarnation Wheel, which turned him into a half-man, half-pig humanoid-pig monster. Zhu Bajie was very greedy, and could not survive without eating ravenously. Staying within the Yunzhan Dong ("cloud-pathway cave"), he was commissioned by Guanyin to accompany Tang Sanzang to India and given the new name Zhu Wuneng.

However, Zhu Bajie's lust for women led him to the Gao Family Village, where he posed as a handsome young man and helped defeat a group of robbers who tried to abduct a maiden. Eventually, the family agreed to let Zhu Bajie marry the maiden. But during the day of the wedding, he drank too much alcohol and accidentally returned to his original form. Being extremely shocked, the villagers ran away, but Zhu Bajie wanted to keep his bride, so he told the bride's father that if after one month the family still did not agree to let him keep the bride, he would take her by force. He also locked the bride up in a separate building. At this point, Tang Sanzang and Sun Wukong arrived at the Gao Family Village and helped defeat him. Renamed Zhu Bajie by Tang Sanzang, he consequently joined the pilgrimage to the West.

His weapon of choice is the jiuchidingpa ("nine-tooth iron rake"). He is also capable of 36 transformations and can travel on clouds, but not as fast as Sun Wukong. However, Zhu is noted for his fighting skills in the water, which he used to combat Sha Wujing, who later joined them on the journey. He is the second strongest member of the team.[citation needed]

Pigsy's lust for women, extreme laziness, and greediness, made his spirituality the lowest in the group, with even the White Dragon Horse achieving more than him, and he remained on Earth and was granted the title "Cleaner of the Altars," with the duty of cleaning every altar at every Buddhist temple for eternity by eating excess offerings.

Sha Wujing / Sandy

editSha Wujing (沙悟淨, "Sand Awakened to Purity"), given the name "Friar Sand", "Sand Monk", "Sandman", "Sand Fairy", "Sand Orc", "Sand Ogre", "Sand Troll", "Sand Oni", "Sand Demon", "Sand Monster", "Sand Hulk", "Sand", or "Sandy" in English, was once a celestial Curtain Lifting General, who stood in attendance by the imperial chariot in the Hall of Miraculous Mist. He was exiled to the mortal world and made to look like a sandman, orc, ogre, troll, oni, demon, monster, or hulk because he accidentally smashed a crystal goblet belonging to the Queen Mother of the West during a Peach Banquet. The now-hideous immortal took up residence in the Flowing Sands River, terrorizing surrounding villages and travelers trying to cross the river. However, he was subdued by Sun Wukong and Zhu Bajie when Tang Sanzang's party came across him. They consequently took him in, as part of the pilgrimage to the West.

Sha Wujing's weapon is a magic wooden staff wrapped in pearly threads, although artwork and adaptations depict him with a Monk's spade staff. He also knows 18 transformation methods and is highly effective in water combat. He is known to be the most obedient, logical, and polite of the three disciples, and always takes care of his master, seldom engaging in the bickering of his fellow disciples. He has no major faults nor any extraordinary characteristics. Due to this, he is sometimes seen as a minor character. He does however serve as the peacekeeper of the group, mediating between Wukong, Bajie, and even Tang Sanzang and others. He is also the person whom Tang Sanzang consults when faced with difficult decisions.

He eventually becomes an arhat at the end of the journey, giving him a higher level of exaltation than Zhu Bajie, who is relegated to cleaning altars, but lower spiritually than Sun Wukong and Tang Sanzang, who are granted Buddhahood.

Sequels

editThe brief satirical novel Xiyoubu (西遊補, "A Supplement to the Journey to the West," c. 1640) follows Sun Wukong as he is trapped in a magical dream world created by the Qing Fish Demon, the embodiment of desire (情, qing). Sun travels back and forth through time, during which he serves as the adjunct King of Hell and judges the soul of the recently dead traitor Qin Hui during the Song dynasty, takes on the appearance of a beautiful concubine and causes the downfall of the Qin dynasty, and even faces Pāramitā, one of his five sons born to the rakshasa Princess Iron Fan,[b] on the battlefield during the Tang dynasty.[14] The events of Xiyoubu take place between the end of chapter 61 and the beginning of chapter 62 of Journey to the West.[15] The author, Dong Yue (董說), wrote the book because he wanted to create an opponent—in this case desire—that Sun could not defeat with his great strength and martial skill.[16]

Notable English-language translations

editAbridged

edit- Monkey: A Folk-Tale of China (1942), an abridged translation by Arthur Waley. For many years, this was the most well-known translation available in English. The Waley translation has also been published as Adventures of the Monkey God, Monkey to the West, Monkey: Folk Novel of China, and The Adventures of Monkey, and in a further abridged version for children, Dear Monkey. Waley noted in his preface that the method adopted in earlier abridgements was "to leave the original number of separate episodes, but drastically reduce them in length, particularly by cutting out dialogue. I have for the most part adopted the opposite principle, omitting many episodes, but translating those that are retained almost in full, leaving out, however, most of the incidental passages in verse, which go very badly into English."[17] The degree of abridgement, 30 out of the 100 chapters (which corresponds to roughly 1/6 of the whole text), and excising most of the verse, has led to a recent critic awarding it the lesser place, as a good retelling of the story.[18] On the other hand, it has been praised as "remarkably faithful to the original spirit of the work."[19]

- The literary scholar Andrew H. Plaks points out that Waley's abridgement reflected his interpretation of the novel as a "folktale"; this "brilliant translation... through its selection of episodes gave rise to the misleading impression that that this is essentially a compendium of popular materials marked by folk wit and humour." Waley followed Hu Shi's lead, as shown in Hu's introduction to the 1943 edition. Hu scorned the allegorical interpretations of the novel as a spiritual as well as physical quest, declaring that they were old-fashioned. He instead insisted that the stories were simply comic. Hu Shi reacted against elaborately allegorical readings of the novel made popular in the Qing dynasty, but does not account for the levels of meaning and the looser allegorical framework which recent scholars in China and the West have shown.[20]

- In 2006, an abridged version of the Anthony C. Yu translation was published by University of Chicago Press under the title The Monkey and the Monk.

- Monkey King: Journey to the West. Translated by Julia Lovell. New York: Penguin. 2021. ISBN 9780143107187. Julia Lovell's translation of selected chapters into lively contemporary English, with an extensive Introduction by Lovell and a Preface by Gene Luen Yang.[21]

Unabridged

edit- The Journey to the West (1977–83), a complete translation in four volumes by Anthony C. Yu, the first to translate the poems and songs which Yu argues are essential in understanding the author's meanings.[22] Yu also supplied an extensive scholarly introduction and notes.[12][23] In 2012, University of Chicago Press issued a revised edition of Yu's translation in four volumes. In addition to correcting or amending the translation and converting romanisation to pinyin, the new edition updates and augments the annotations, and revises and expands the introduction in respect to new scholarship and modes of interpretation.

- Journey to the West (1982–84), a complete translation in four volumes by William John Francis Jenner.[24] Readable translation without scholarly apparatus.[25]

Media adaptations

editSaiyūki (西遊記), also known by its English title Monkey and commonly referred to by its title song, "Monkey Magic," is a Japanese television series starring Masaaki Sakai, produced by Nippon TV and International Television Films in association with NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) and broadcast from 1978 to 1980 on Nippon TV. It was translated into English by the BBC.

In the 1980s, China Central Television (CCTV) produced and aired a TV adaptation of Journey to the West under the same name as the original work. A second season was produced in the late 1990s covering portions of the original work that the first season skipped over.

In 1988, the Japanese anime series Doraemon released a movie named Doraemon: The Record of Nobita's Parallel Visit to the West which is based on the same story.

In 1997, Brooklyn-based jazz composer Fred Ho premiered his jazz opera Journey to the East, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, which he developed into what he described as a "serial fantasy action-adventure music/theater epic," Journey Beyond the West: The New Adventures of Monkey. Ho's pop-culture infused take on the story of the Monkey King has been performed to great acclaim.[citation needed]

A video game adaptation titled Enslaved: Odyssey to the West was released in October 2010 for PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, and Microsoft Windows. It was developed by Ninja Theory and published by Bandai Namco Entertainment. The voice and motion capture for the main protagonist, 'Monkey', were provided by Andy Serkis.

On 20 April 2017, Australia's ABC, TVNZ, and Netflix announced production was underway in New Zealand on a new live-action television series, The New Legends of Monkey, to premiere globally in 2018. The series, which is based on Journey to the West, is made up of 10 half-hour episodes. While there has been enthusiasm for the new series, it has also attracted some criticism for "whitewashing,"[26] since none of the core cast are of Chinese descent, with two of the leads having Tongan ancestry[27] while only one, Chai Hansen, is of half-Asian (his father is Thai) descent.[28]

More recently in 2017, Viki and Netflix hosted a South Korean show called A Korean Odyssey; a modern comedy retelling that begins with the release of Sun Wukong/Son O-Gong and the reincarnation of Tang Sanzang/Samjang.

In August 2020, Game Science Studios announced a video game called Black Myth: Wukong.[29] It was released on 20 August 2024 for PlayStation 5 and PC. It is also slated to release at a later date for the Xbox Series X/S. The plot of the game is set after the main events of the novel.

On May 16, 2020, The Lego Group released the theme, Lego Monkie Kid, to which Journey of the West was credited as the main inspiration, featuring many characters from the original work. Four days later on May 20, an animated television series pilot was released to coincide with the theme, and was later picked up for production and released serially starting in September 2020.

See also

editExplanatory notes

editReferences

edit- ^ Yu (2012), p. 18.

- ^ Kherdian, David (2005). Monkey: A Journey to the West. p. 7.

is probably the most popular book in all of East Asia.

- ^ "Journey to the West | Author, Summary, Characters, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 21 August 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ "Monkeying Around with the Nobel Prize: Wu Chen'en's "Journey to the West"". Los Angeles Review of Books. 13 October 2013.

It is a cornerstone text of Eastern fiction: its stature in Asian literary culture may be compared with that of The Canterbury Tales or Don Quixote in European letters.

- ^ "ANiMAL-Art Science Nature Society". National Palace Museum. 26 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d Chang (2010), p. 55.

- ^ Yu (2012), pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b c Jenner 1984

- ^ a b "Journey to the West". Encyclopedia Britannica. 10 May 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Yu (2012), p. 10.

- ^ Hu Shih (1942). "Introduction". In Arthur Waley (ed.). Monkey. Translated by Arthur Waley. New York: Grove Press. pp. 1–5.

- ^ a b Lattimore, David (6 March 1983). "The Complete 'Monkey'". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Sun, Hongmei (2024). "Playing Journey to the West". In Guo, Li; Eyman, Douglas; Sun, Hongmei (eds.). Games & Play in Chinese & Sinophone Cultures. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295752402.

- ^ Dong, Yue; Wu, Chengẻn (2000). The Tower of Myriad Mirrors: A Supplement to Journey to the West. Michigan classics in Chinese studies. Translated by Lin, Shuen-fu; Schulz, Larry James. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, The University of Michigan. ISBN 9780892641420.

- ^ Dong & Wu (2000), p. 5.

- ^ Dong & Wu (2000), p. 133.

- ^ Wu Ch'eng-en; Arthur Waley (1984) [1942]. Monkey. Translated by Arthur Waley. New York: Grove Press. p. 7. ISBN 9780802130860.

- ^ Plaks, Andrew (1977). "Review: "The Journey to the West" by Anthony C. Yu". MLN. 92 (5): 1116–1118. doi:10.2307/2906900. JSTOR 2906900.

- ^ Ropp, Paul S. (1990). "The Distinctive Art of Chinese Fiction". Heritage of China: Contemporary Perspectives on Chinese Civilisation. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 321 note 12. ISBN 9780520064409.

- ^ Plaks (1994), pp. 274–275.

- ^ Van Fleet, John Darwin (31 January 2021). "Monkey King (Review)". Asian Review of Books. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ University of Chicago Press: HC ISBN 0-226-97145-7, ISBN 0-226-97146-5, ISBN 0-226-97147-3, ISBN 0-226-97148-1; PB ISBN 0-226-97150-3, ISBN 0-226-97151-1; ISBN 0-226-97153-8; ISBN 0-226-97154-6.

- ^ Plaks (1994), p. 283.

- ^ Foreign Languages Press Beijing. (ISBN 0-8351-1003-6, ISBN 0-8351-1193-8, ISBN 0-8351-1364-7); 1993 edition in four volumes: ISBN 978-7-119-01663-4; 2003 edition in six volumes with original Chinese on left page, English translation on right page: ISBN 7-119-03216-X

- ^ Plaks (1994), p. 283.

- ^ Whitehead, Mat (20 April 2017). "'Monkey Magic' Returns As Filming Begins On 'The Legend of Monkey' In New Zealand". Huffington Post. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Ma, Wenlei (26 January 2018). "The New Legends of Monkey writer responds to 'whitewashing' accusations". news.com.au.

- ^ "Chai Romruen". IMDb. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ "Gorgeous Action-RPG Black Myth: Wukong Revealed with Extended Gameplay Trailer - IGN". 20 August 2020.

Further reading

edit- Bhat, R. B.; Wu, C. (2014). Xuan Zhang's mission to the West with Monkey King. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

- Chang, Kang-i Sun (2010). "Literature of the early Ming to mid-Ming (1375–1572)". In Chang, Kang-i Sun (ed.). The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, Volume II: From 1375. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–62. ISBN 978-0-521-85559-4.

- Chen, Minjie, "Monkey Craze", Cotsen Children's Library blog, Princeton, 12 Feb 2016. Accessed 22 Aug 2024.

- Chen, Minjie, "A Chinese Classic Journeys to the West: Julia Lovell’s Translation of 'Monkey King'", Los Angeles Review of Books, 5 Oct 2021. Accessed 22 Aug 2024.

- Fu, James S. (1977). Mythic and Comic Aspects of the Quest. Singapore: Singapore University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gray, Gordon; Wang, Jianfen (2019). "The Journey to the West: A Platform for Learning About China Past and Present". Education About Asia. 24 (1).

- Hsia, C.T. (1968). "The Journey to the West". The Classic Chinese Novel. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 115–164.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jenner, William John Francis (1984). "Translator's Afterword". Journey to the West. Vol. 4 (Seventh ed.). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. pp. 2341–2343.

- ——— (3 February 2016). "Journeys to the East, 'Journey to the West". Los Angeles Review of Books.

- Kao, Karl S.Y. (October 1974). "An Archetypal Approach to Hsi-yu chi". Tamkang Review. 5 (2): 63–98.

- Plaks, Andrew (1987). The Four Masterworks of the Ming Novel. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 183–276.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ——— (1994). "The Journey to the West". In Miller, Barbara S. (ed.). Masterworks of Asian Literature in Comparative Perspective. New York: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 272–284.

- Shi Changyu 石昌渝 (1999). "Introduction". Journey to the West. Vol. 1. Translated by Jenner, William John Francis (Seventh ed.). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. pp. 1–22.

- Wang, Richard G.; Xu, Dongfeng (2016). "Three Decades' Reworking on the Monk, the Monkey, and the Fiction of Allegory". The Journal of Religion. 96 (1): 102–121. doi:10.1086/683988. S2CID 170097583.

- Wasserstrom, Jeffrey (10 December 2020). "Julia Lovell on the Monkey King's Travels Across Borders: A Conversation". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- Yu, Anthony C. (February 1983). "Two Literary Examples of Religious Pilgrimage: The Commedia and the Journey to the West". History of Religions. 22 (3): 202–230. doi:10.1086/462922. S2CID 161410156.

- ——— (2012). "Introduction". Journey to the West. Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–96.

External links

edit- Journey to the West from the Gutenberg Project (Traditional Chinese)

- Journey to the West from Xahlee (Simplified Chinese)

- Story of Sun Wukong and the beginning of Journey to the West with manhua

- 200 images of Journey to the West by Chen Huiguan, with a summary of each chapter (Archived Link)

- Journey to the West 西遊記 Chinese text with embedded Chinese-English dictionary

- Journey to the West Journey to the West(English)