The United States elections of 1788–1789 were the first federal elections in the United States following the ratification of the United States Constitution in 1788. In the elections, George Washington was elected as the first president and the members of the 1st United States Congress were selected.

| Presidential election year | |

| Next Congress | 1st |

|---|---|

| Presidential election | |

| Electoral vote | |

| George Washington | 69 |

| |

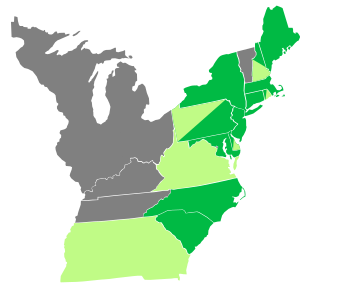

| Presidential election results map. Green denotes states won by Washington. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes cast by each state.[note 1] | |

| Senate elections | |

| Overall control | Pro-Administration gain |

| Seats contested | All 26 seats[1] |

| Net seat change | Pro-Administration +13[2] |

| |

| Senate results Pro-Administration Anti-Administration Territories | |

| House elections | |

| Overall control | Pro-Administration gain |

| Seats contested | All 59 voting members |

| Net seat change | Pro-Administration +37[2] |

| |

| House of Representatives results Pro-Administration Anti-Administration Territories | |

Formal political parties did not exist, as the leading politicians of the day largely distrusted the idea of "factions." However, in the years after the ratification of the Constitution, Congress would become broadly divided by the economic policies of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, with the Pro-Administration faction supporting those policies. Opposing them was the Anti-Administration faction, which sought a smaller role for the federal government.[3] In these elections, the Pro-Administration faction won majorities in both houses of Congress.

Meanwhile, General George Washington was elected as the country's first president, while John Adams, who finished with the second largest number of electoral votes, was elected as the first vice president.

Presidential election

editThe presidential election of 1788–1789 was the first election of a federal head of state or head of government in United States history. Prior to the ratification of the United States Constitution in 1788, the U.S. had been governed under the Articles of Confederation, which provided for a very limited central government; what power that did exist was vested in the Congress of the Confederation, a unicameral legislature consisting of representatives elected by the states. The Congress of the Confederation had elected a president, but this position was largely ceremonial and was not equivalent to the presidency that was established by the United States Constitution.

Under the U.S. Constitution, the president was chosen by the Electoral College, which consisted of electors selected by each state. Prior to the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment, each elector cast two votes; the individual who received the most electoral votes would become president, while the individual who received the second-most electoral votes would become vice president. If no individual received votes from a majority of the electors, or if two individuals tied for the most votes, then the House of Representatives would select the president in a contingent election. Under the Constitution, each state determines its own method of choosing presidential electors; in the 1788–1789 presidential election, many electors were appointed by state legislators, while others were chosen through elections. In the states that did hold elections, suffrage was generally restricted to white men who owned property.

No party made a nomination for the presidency in the 1788–1789 presidential election, but several individuals vied for electoral votes. After his service in the American Revolutionary War, General George Washington was the first choice of many for president, but Washington was somewhat reluctant to re-enter public service.[4] The American public at large, however, wanted Washington to be the nation's first president.[5] The first U.S. presidential campaign was, to some degree, what today would be called a grassroots effort to convince Washington to accept the office.[5] Alexander Hamilton was one of the most dedicated in his efforts to get Washington to accept the presidency, as he foresaw himself receiving a powerful position in the administration.[6]

Less certain was the choice for the vice presidency, which contained little definitive job description in the constitution. The only official role of the vice president was as the President of the United States Senate, a duty unrelated to the executive branch.[7] Because Washington was from Virginia, Washington (who remained neutral on the candidates) assumed that a vice president would be chosen from Massachusetts to provide sectional balance between the Northern states and the Southern states.[8] In an August 1788 letter, Thomas Jefferson wrote that he considered John Adams, John Hancock, John Jay, James Madison, and John Rutledge to be contenders for the vice presidency.[9] Fearing an electoral college tie that could end with Adams winning the presidency, Alexander Hamilton arranged for several electors to vote for other candidates, including John Jay, who finished with the third most electoral votes.[10]

On April 6, 1789, the House and Senate, meeting in joint session, counted the electoral votes and certified that Washington had received electoral votes from each of the 69 electors that had cast votes, and thus had been elected president. They also certified that Adams, with 34 electoral votes, had been elected as vice president.[11] The other 35 electoral votes were divided among: John Jay (9), Robert H. Harrison (6), John Rutledge (6), John Hancock (4), George Clinton (3), Samuel Huntington (2), John Milton (2), James Armstrong (1), Benjamin Lincoln (1), and Edward Telfair (1).[12] Only ten of the thirteen states cast electoral votes; North Carolina and Rhode Island did not participate as they had not yet ratified the Constitution, while the New York legislature failed to appoint its allotted electors in time.[13]

Congressional elections

editIn 1788 and 1789, there were no political parties, but the major political split was between federalists who favored the ratification of the Constitution and anti-federalists who favored either completely rejecting the Constitution or only ratifying the document after making major changes to it. For example, in the election to represent Virginia's 5th congressional district, James Madison, a federalist who had played a major role in designing and ratifying the Constitution, defeated James Monroe, an anti-federalist who favored major changes to the Constitution. In many elections, local issues and the personal popularity of the candidates played a more important role than positions on the Constitution and other national issues.

Retrospectively, political scientists and historians have divided the 1st Congress into members of the Pro-Administration and Anti-Administration factions.[citation needed] The Pro-Administration faction would generally support the centralizing economic policies of the Washington administration and Secretary of State Alexander Hamilton. The Anti-Administration faction generally opposed those policies, instead favoring states' rights and a weaker federal government. The Pro-Administration faction overlapped heavily with both the federalists who favored the ratification of the Constitution and the later Federalist Party, while the Anti-Administration faction overlapped with the anti-federalists and the later Democratic-Republican Party. Using this divide as a lens through which to view the elections, the Pro-Administration faction won majorities in both houses of Congress.[14][15] Factional alignment would be fluid for much of the Washington administration.

See also

editFootnotes

editReferences

edit- ^ Not counting special elections.

- ^ a b Congressional seat gain figures only reflect the results of the regularly-scheduled elections, and do not take special elections into account.

- ^ Reichley, A. James (2000). The Life of the Parties (Paperback ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 29–30.

- ^ Unger 2015, p. 51

- ^ a b Knott, Stephen. "George Washington: Campaigns and Elections". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Chernow 2010, p. 548

- ^ Albert, Richard (2005). "The Evolving Vice Presidency". Temple Law Review. 78. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University of the Commonwealth System of Higher Education: 811, at 816–19. ISSN 0899-8086. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Chernow 2010, p. 551

- ^ Meacham 2012, p. 220

- ^ "Presidential elections". History.com. History Channel. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ Ferling 2009, pp. 270–274

- ^ "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". College Park, Maryland: Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on July 20, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ "Presidential Election of 1789". Mount Vernon, Virginia: Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, George Washington's Mount Vernon. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ "Party Divisions of the House of Representatives". United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ^ "Party Division in the Senate, 1789-Present". United States Senate. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

Works cited

edit- Chernow, Ron (2010). Washington: A Life. London: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-266-7.

- Ferling, John (2009). The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 1-59691-465-3.

- Meacham, Jon (2012). Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. New York City: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6766-4.

- Unger, Harlow (2015). "Mr. President": George Washington and the Making of the Nation's Highest Office (paperback ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82353-4.