The 1919 Coatesville call to arms was when the black community of Coatesville, Pennsylvania formed a large armed group to prevent a rumoured lynching. Only later when the armed group had surrounded the jail to prevent the lynching did they learn that there was no suspect and no white lynch mob.

| Part of Red Summer | |

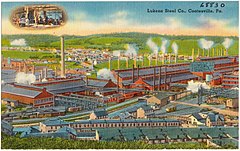

Coatesville and its steel plant | |

| Date | Late July 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | Coatesville, Pennsylvania, United States |

1911 lynching of Zachariah Walker

editIn 1911, steelworker Zachariah Walker was lynched in Coatesville; he had left his wife and children in Virginia while seeking better work. This African-American man was accused of killing white mill policeman Edgar Rice, a popular figure in town. Walker claimed self-defense and was hospitalized after his arrest.[1] He was dragged from the hospital and burned to death in front of a mob of hundreds in a field south of the city.[2] Fifteen men and teenage boys were indicted, but all were acquitted at trials. The lynching was the last in Pennsylvania and is said to have left a permanent stain on the city's image.[3]

Call to arms

editOn July 6, 1919, a fourteen-year-old white girl, Esther Hughes, was allegedly attacked by a black man. Esther's boy companion was tied to a tree and another girl that was with Esther was able to run away.[4] On July 8, a rumour surfaced that a suspect had been arrested and that a white mob was assembling to lynch him. Scared by the 1911 lynching of Zachariah Walker a large group of Coatesville's African Americans armed themselves and marched downtown to protect the jail from the white mob. When they arrived Mayor Swing and local Rev. T. W. McKinney assured the crowd that the rumor was false. A number of leaders of the march were arrested and charged with inciting a riot even though they had assembled to stop a rumored white riot.[5] All of the nine people arrested were later released.[5]

Aftermath

editThis uprising was one of several incidents of civil unrest that began in the so-called American Red Summer, of 1919. The Summer consisted of terrorist attacks on black communities, and white oppression in over three dozen cities and counties. In most cases, white mobs attacked African American neighborhoods. In some cases, black community groups resisted the attacks, especially in Chicago and Washington, D.C. Most deaths occurred in rural areas during events like the Elaine Race Riot in Arkansas, where an estimated 100 to 240 black people and 5 white people were killed. Also occurring in 1919 were the Chicago Race Riot and Washington D.C. race riot which killed 38 and 39 people respectively, and with both having many more non-fatal injuries and extensive property damage reaching up into the millions of dollars.[6]

See also

editBibliography

editNotes

- ^ Mowday 2003, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Catalano 2004.

- ^ Rucker & Upton 2007, pp. 95–96.

- ^ The Daily Banner 1919, p. 1.

- ^ a b Krugler 2014, p. 284.

- ^ The New York Times 1919.

References

- Catalano, Laura (August 13, 2004). "Storm water concerns officials". Daily Local News. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Mowday, Bruce Edward (2003). Images of America: Coatesville. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738511986. - Total pages: 128

- The Daily Banner (July 9, 1919). "Coatesville Negroes Riot". The Daily Banner. Cambridge, Maryland: Harrington Henry & Co. pp. 1–4. ISSN 2475-4293. OCLC 18778410. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- Krugler, David F. (2014). 1919, The Year of Racial Violence. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107061798. - Total pages: 332

- The New York Times (October 5, 1919). "For Action on Race Riot Peril". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- Rucker, Walter C.; Upton, James N. (2007). Encyclopedia of American Race Riots, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313333026. - Total pages: 930

- Smith, Eric S. (August 13, 2011). "Zachariah Walker's lynching haunts the city". Daily Local News. Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2019.