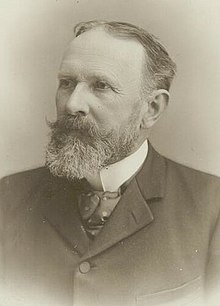

The 1919 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the Swiss poet Carl Spitteler (1845–1924) "in special appreciation of his epic, Olympian Spring."[1] Spitteler received his prize the following year after the Nobel Committee decided that none of the 1919 nominations met the criteria as outlined in Alfred Nobel's will.[1] He is the first Swiss recipient of the literature prize.[2]

| Carl Spitteler | |

"in special appreciation of his epic, Olympian Spring." | |

| Date |

|

| Location | Stockholm, Sweden |

| Presented by | Swedish Academy |

| First awarded | 1901 |

| Website | Official website |

Laureate

editUnder the pseudonym of Carl Felix Tandem, Spitteler published his first poetry collection, Prometheus und Epimetheus ("Prometheus und Epithemus") in 1881, showing contrasts between ideals and dogmas through the two mythological figures of the titles. From 1900 to 1905, he wrote the epic Der olympische Frühling ("Olympian Spring"), an allegory written in iambic hexameter, mixing fantastic, naturalistic, religious and mythological themes that deal with human relationship with the universe. The novel Imago (1906) which examines the role of the unconscious in the conflict between a creative mind and the middle-class restrictions with internal monologue, influenced Carl Jung in his usage of "imago" in Jungian psychoanalysis.[3][4]

Olympian Spring

editSpitteler's epic Der olympische Frühling ("Olympian Spring"), written between 1900 and 1905, is about the establishment of the rule of the Greek gods over the world.[5] An iambic hexameter allegory, the epic explores universal concerns such as faith, morality, hope, despair, and ethics in a setting among the Greek gods, at the same time, examining themes related to fantasy, religion, and mythology.[5][6] It is originally published in four volumes: "Overture," "Hera the Bride," "High Tide," and "End and Change."[5] He later revised the epic in 1909 after which it achieved immediate popularity in Switzerland and Germany, gaining thousands of publications.[6][7]

Deliberations

editNominations

editSpitteler was first nominated in 1912 by professors in Bern and Zurich after gaining steady success in revising Olympian Spring in 1910. Since then, he received annual recommendations from various academics and Nobel Committee members – eighteen nominations in total – until he was eventually awarded in 1920.[8]

In total, the Nobel Committee for Literature received 18 nominations for 12 authors such as Juhani Aho, Hans E. Kinck, Erik Axel Karlfeldt (awarded in 1931) and Per Hallström. Five of the nominees were newly nominated: Władysław Reymont (awarded in 1924), John Galsworthy (awarded in 1932), Ebenezer Howard, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Arno Holz. No women were nominated for this year.[9]

The authors Leonid Andreyev, L. Frank Baum, Matilda Betham-Edwards, Andrew Carnegie, Petre P. Carp, Ada Langworthy Collier, Ferdinando Fontana, John Fox Jr., Weedon Grossmith, Ernst Haeckel, Gustav Landauer, Paul Lindau, Rosa Luxemburg, Mary Ann Maitland, Alice Moore McComas, Barbu Nemțeanu, Jane Lippitt Patterson, Anne Isabella Thackeray Ritchie, Kolachalam Srinivasa Rao, Abraham Valdelomar, Guido von List, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, Kazimierz Zalewski died in 1919 without having been nominated for the prize.

| No. | Nominee | Country | Genre(s) | Nominator(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Juhani Aho (1861–1921) | Finland | novel, short story |

|

| 2 | John Galsworthy (1867–1933) | Great Britain | novel, drama, essays, short story, memoir | Erik Axel Karlfeldt (1864–1931) |

| 3 | Ángel Guimerá Jorge (1845–1924) | Spain | drama, poetry | unnamed nominator |

| 4 | Per Hallström (1866–1960) | Sweden | short story, drama, poetry | Nathan Söderblom (1866–1931) |

| 5 | Arno Holz (1863–1929) | Germany | poetry, drama, essays | 40 German authors |

| 6 | Ebenezer Howard (1850–1928) | Great Britain | essays | Christen Collin (1857–1926) |

| 7 | Alois Jirásek (1851–1930) | Czechoslovakia | novel, drama | Czech Academy of Sciences |

| 8 | Erik Axel Karlfeldt (1864–1931) | Sweden | poetry |

|

| 9 | Hans Ernst Kinck (1865–1926) | Norway | philology, novel, short story, drama, essays |

|

| 10 | Władysław Reymont (1867–1925) | Poland | novel, short story | Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences |

| 11 | Carl Spitteler (1845–1924) | Switzerland | poetry, essays | Verner von Heidenstam (1859–1940) |

| 12 | Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874–1929) | Austria | novel, poetry, drama, essays | Gerhart Hauptmann (1862–1946) |

Prize decision

editThe members of the Swedish Academy voted that the 1919 Nobel Prize in Literature should be awarded to the Swedish poet Erik Axel Karlfeldt. But Karlfeldt promptly declined the prize, explaining that he could not accept it because of his position as the permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy. Although the Academy wanted to award him, Karlfeldts reasons for not accepting the prize he was offered was met with admiration from his colleagues in the Academy.[10] Shortly after his death, Karlfeldt was posthumously awarded the 1931 Nobel Prize in Literature.[10]

After Karlfeldt's refusal, the prize decision for the 1919 prize was postponed to the following year when the Academy decided to award the Swiss poet Carl Spitteler.

References

edit- ^ a b The Nobel Prize in Literature 1919 nobelprize.org

- ^ "Nobel Prize winner beloved by Swiss; Carl Spitteler, Poet and Essayist, at 75 Lives Retired Life on Lake Lucerne". New York Times. 14 November 1920. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Carl Spitteler – Facts nobelprize.org

- ^ "Carl Spitteler | Swiss poet". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ a b c Gilbert Highet (1952). "A Neglected Masterpiece: Olympian Spring". The Antioch Review. 12 (3): 338–346. JSTOR 4609578. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Carl Friedrich Georg Spitteler". encyclopedia.com. 8 June 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Award ceremony speech – Literature 1919 nobelprize.org

- ^ Nomination archive – Carl Spitteler nobelprize.org

- ^ Nomination archive – Literature 1919 nobelprize.org

- ^ a b "Karlfeldt och Nobelpriset". karlfeldt.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26.

External links

edit- Award ceremony speech – Literature 1919 nobelprize.org