The 1984 Dallas Grand Prix was a one-off Formula One motor race held on July 8, 1984 at Fair Park in Dallas, Texas. It was the only running of the Dallas Grand Prix as a Formula One race, and the ninth race of the 1984 Formula One World Championship.

| 1984 Dallas Grand Prix | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Race 9 of 16 in the 1984 Formula One World Championship | |||

| |||

| Race details | |||

| Date | July 8, 1984 | ||

| Official name | Stroh's Dallas Grand Prix | ||

| Location | Fair Park, Dallas, Texas | ||

| Course | Temporary street circuit | ||

| Course length | 3.901 km (2.424 miles) | ||

| Distance | 67 laps, 261.37 km (162.41 miles) | ||

| Scheduled distance | 68 laps, 265.268 km (164.830 miles) | ||

| Weather | Sunny with temperatures reaching up to 100 °F (38 °C); wind speeds of 14 miles per hour (23 km/h)[1] | ||

| Pole position | |||

| Driver | Lotus-Renault | ||

| Time | 1:37.041 | ||

| Fastest lap | |||

| Driver |

| McLaren-TAG | |

| Time | 1:45.353 on lap 22 | ||

| Podium | |||

| First | Williams-Honda | ||

| Second | Ferrari | ||

| Third | Lotus-Renault | ||

|

Lap leaders | |||

The 67-lap race was held in very hot weather on a disintegrating track, and was won by Finnish driver Keke Rosberg, driving a Williams-Honda, with Frenchman René Arnoux second in a Ferrari and Italian Elio de Angelis third in a Lotus-Renault. Englishman Nigel Mansell took pole position in the other Lotus-Renault and led the first half of the race, before suffering a gearbox failure at the very end and collapsing from exhaustion while trying to push his car over the finish line.

Summary

editKeke Rosberg of Finland won his only race of the season at the Dallas Grand Prix. The race was one of only two races in 1984 where both of the year's dominant McLarens driven by Niki Lauda and Alain Prost did not score (Belgium being the other), and gave Honda their first turbocharged Grand Prix win and also their first Grand Prix win since the 1967 Italian Grand Prix. René Arnoux's Ferrari was the only other car on the lead lap at the end after starting from the pit lane due to an electrical fault on the warm up lap, while Elio de Angelis came home third for Lotus. It was the only race of the season that cars using Goodyear tyres filled all three podium positions. Only 8 cars finished the race, due to crashes or engine failures in up to 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 °C) heat, and also the track was breaking up very badly, as in the 1980 Argentine Grand Prix.

The event was conceived as a way to demonstrate Dallas's status as a "world-class city"[2][3] and overcame 100 °F (38 °C) heat, a disintegrating track surface and weekend-long rumors of its cancellation.[2][4] Famous U.S. racing driver and race car builder Carroll Shelby, who grew up in Dallas, served as race director.[3] Preparations for the race were marred by managerial difficulties and conflicts between F1 personnel and local race organizers, and opinions on the venue were mixed. In statements to the Dallas Times Herald, Lotus team principal Peter Warr said he was "super impressed" with Dallas, but F1 leader Bernie Ecclestone—commenting on the repurposing of the Fair Park Coliseum, which was normally used for livestock shows, as a race garage—said “We don’t normally work in cowshit”.[3]

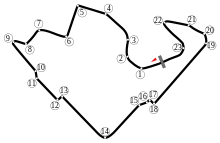

The tight and twisty course was laid out on the Texas State Fair Grounds with help from United States Grand Prix West founder Chris Pook, and featured two hairpin curves. While the layout was seen as interesting and was generally well received by the drivers (though some thought one or two of the chicanes made it tighter than it needed to be), all had issues with the lack of run-off areas and the crumbling surface which during the race itself made the track more like a rallycross track than a Grand Prix circuit. It was bubbling before qualifying, and after a few laps, it began to break apart.[2]

After the first practice on Friday, the Lotus drivers, Nigel Mansell and de Angelis, who both started from the front row with Mansell recording his first career pole position, said the temporary course was the roughest circuit they had ever driven. Nelson Piquet wondered whether the track, the drivers or the cars would break first in the oppressive heat. Afternoon qualifying saw temperatures continue to rise past 100 °F (38 °C), and Goodyear recorded the highest track temperature in their 20 years of racing, 150 °F (66 °C).

Dallas was the first time since the 1978 Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort that both Lotus drivers qualified on the front row of the grid. Back then, it was 1978 World Champion Mario Andretti and his teammate Ronnie Peterson who qualified 1–2 in the revolutionary Lotus 79.

After the Renault celebrity race on Saturday, Stirling Moss introduced himself to former US President Jimmy Carter in the VIP suite, saying, "I have never shaken hands with a president." Carter, to the surprise of many (due to the general belief that Formula One drivers weren't as well known in America as the Indy 500 and NASCAR drivers), recognized Moss immediately.[4]

The race was scheduled to start at 11 am on Sunday, three hours earlier than usual, because of the heat, with the 30-minute warm-up planned for 7:45 am. This was apparently too early for French Williams driver Jacques Laffite, who arrived at the circuit in his pajamas.[2] The warm-up was delayed and then canceled however, because a 50-lap Can-Am race on Saturday had damaged the circuit so badly that emergency repairs had gone on all night, and would continue until 30 minutes before the start (the repairs involved a backhoe digging up the broken asphalt and replacing it with quick-dry cement). Niki Lauda and Alain Prost tried to arrange a boycott among the drivers, but Rosberg insisted they should race.[4]

I don't know what all the fuss is about. We'll all complain and bind right up until the start time and then we'll go out and race as usual. We've come all this way and the race is all set up. Track surface or no track surface, you know as well as I do, we'll race.

— Keke Rosberg speaking before the race.[5]

Ecclestone did not want to have 90,000 disappointed fans at the circuit, and viewers around the world, so the race went off with Larry Hagman (J. R. Ewing from the television series Dallas) waving the green flag to start the parade lap.[2][4]

Mansell led for almost half the race from his first pole position. Derek Warwick overtook de Angelis, whose engine was suffering from a misfire, and pulled alongside Mansell several times, but could not get around. He retired after an attempt to pass on lap 11 resulted in a spin. Lauda was next to challenge Mansell, but he was passed by de Angelis when the latter's engine began to run on all six cylinders.

The first five cars (Mansell, de Angelis, Lauda, Rosberg, Prost) were now running as a group, and on lap 14, Rosberg passed Lauda for third and closed up on the two Lotuses. He passed de Angelis on lap 18, and soon was looking for a way past Mansell. Arnoux, having qualified fourth, had been unable to start his car on the grid, and began the race from the back of the pack. By the end of the first lap, he had already passed seven cars and now he and Piquet were closing on the group of leaders.

Rosberg, after briefly trading places with Prost, who had gotten by Lauda and de Angelis, finally forced Mansell into a big enough mistake for him to take the lead. Within three laps, Mansell, whose front tires were quickly fading, had dropped three more places before pitting on lap 38. Piquet became the ninth car to retire because of contact with the wall, and Arnoux moved into the top five.

Prost took the lead from Rosberg on lap 49, and quickly opened a 7.5-second lead, but eight laps later struck a wall and damaged a wheel rim. Rosberg inherited a lead of 10 seconds over Arnoux, and, thanks in part to a special skull cap driver cooling system, held on to score his only victory of the year for Williams, as the two-hour limit was reached one lap short of the scheduled 68.

De Angelis came home third, comfortably ahead of Laffite in the second Williams. De Angelis's teammate Mansell made contact with the wall. Mansell coasted around the last corner, visor up and seat belts hanging over the side of the car. As his car slowed on the home straight, he leaped from his black Lotus and tried to push it to the end, but collapsed from exhaustion and the oppressive heat before reaching the finish line. He was classified sixth, three laps behind.

The oppressive heat was a factor of the Dallas Grand Prix becoming a one-off, and the event was replaced by the following year's Australian Grand Prix. Formula One has since returned to the state of Texas, hosting the United States Grand Prix since 2012 at the newly constructed Circuit of the Americas, located in the state capital of Austin. However, the race in Austin has always been held in October or November, away from the Texas summer.

The heat also caused some drivers to take some countermeasures to cope with the heat; such as Rosberg's water-cooled skullcap (a common device in the NASCAR circuit); Piercarlo Ghinzani, who finished fifth after overtaking the collapsed Mansell, having a bucket of cold water thrown over him during a pit stop; and Huub Rothengatter, who dashed straight to a spectator area after he retired from the race, where he commandeered several cups of water "for pouring over his nether regions…".[6]

Ayrton Senna had retired from the race on lap 47 while running fourth after hitting the wall. On coming back to the pits, he was furious, telling his race engineer Pat Symonds: "I just cannot understand how I did that. I was taking it no differently than I had been before. The wall must have moved." His team did not believe him and Senna persuaded them to inspect the wall after the race, only for them to find that the barrier had indeed been moved by an earlier crash, moving only a mere 4–10 mm (0.2–0.4 in) into the track.[6][7][8] Symonds recalled his amazement in 2004, saying: "That was when the precision to which he was driving really hit home for me. Don't forget, this was a guy in his first season of F1, straight out of F3...".[7]

Classification

editQualifying

edit| Pos | No | Driver | Constructor | Q1 | Q2 | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | Nigel Mansell | Lotus-Renault | 1:37.041 | no time | — |

| 2 | 11 | Elio de Angelis | Lotus-Renault | 1:37.635 | no time | +0.594 |

| 3 | 16 | Derek Warwick | Renault | 1:38.285 | 1:37.708 | +0.667 |

| 4 | 28 | René Arnoux | Ferrari | 1:37.785 | 1:39.633 | +0.744 |

| 5 | 8 | Niki Lauda | McLaren-TAG | 1:37.987 | 1:41.835 | +0.946 |

| 6 | 19 | Ayrton Senna | Toleman-Hart | 1:38.256 | no time | +1.215 |

| 7 | 7 | Alain Prost | McLaren-TAG | 1:38.544 | 1:41.344 | +1.503 |

| 8 | 6 | Keke Rosberg | Williams-Honda | 1:38.767 | 1:39.438 | +1.726 |

| 9 | 27 | Michele Alboreto | Ferrari | 1:38.793 | 1:42.005 | +1.752 |

| 10 | 15 | Patrick Tambay | Renault | 1:38.907 | 1:40.790 | +1.866 |

| 11 | 2 | Corrado Fabi | Brabham-BMW | 1:38.960 | 1:41.097 | +1.919 |

| 12 | 1 | Nelson Piquet | Brabham-BMW | 1:39.439 | 1:39.630 | +2.398 |

| 13 | 14 | Manfred Winkelhock | ATS-BMW | 1:39.860 | 1:40.289 | +2.189 |

| 14 | 23 | Eddie Cheever | Alfa Romeo | 1:39.911 | 1:40.773 | +2.870 |

| 15 | 20 | Johnny Cecotto | Toleman-Hart | 1:40.027 | no time | +2.986 |

| 16 | 26 | Andrea de Cesaris | Ligier-Renault | 1:40.095 | 1:41.464 | +3.054 |

| 17 | 4 | Stefan Bellof | Tyrrell-Ford | 1:40.336 | 1:41.680 | +3.295 |

| 18 | 24 | Piercarlo Ghinzani | Osella-Alfa Romeo | 1:41.176 | 1:42.439 | +4.135 |

| 19 | 25 | François Hesnault | Ligier-Renault | 1:41.303 | no time | +4.262 |

| 20 | 18 | Thierry Boutsen | Arrows-BMW | 1:41.840 | 1:41.318 | +4.277 |

| 21 | 22 | Riccardo Patrese | Alfa Romeo | 1:41.328 | 1:50.277 | +4.287 |

| 22 | 17 | Marc Surer | Arrows-BMW | 1:44.503 | 1:42.592 | +5.551 |

| 23 | 21 | Huub Rothengatter | Spirit-Hart | 1:43.084 | 1:43.735 | +6.043 |

| 24 | 9 | Philippe Alliot | RAM-Hart | 1:43.222 | no time | +6.181 |

| 25 | 5 | Jacques Laffite | Williams-Honda | 1:43.304 | 1:46.257 | +6.263 |

| 26 | 10 | Jonathan Palmer | RAM-Hart | 1:44.676 | 1:47.566 | +7.635 |

| DNQ | 3 | Martin Brundle | Tyrrell-Ford | 2:31.960 | no time | +54.919 |

Race

edit| Pos | No | Driver | Constructor | Laps | Time/Retired | Grid | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | Keke Rosberg | Williams-Honda | 67 | 2:01:22.617 | 8 | 9 |

| 2 | 28 | René Arnoux | Ferrari | 67 | + 22.464 | 4 | 6 |

| 3 | 11 | Elio de Angelis | Lotus-Renault | 66 | + 1 Lap | 2 | 4 |

| 4 | 5 | Jacques Laffite | Williams-Honda | 65 | + 2 Laps | 24 | 3 |

| 5 | 24 | Piercarlo Ghinzani | Osella-Alfa Romeo | 65 | + 2 Laps | 18 | 2 |

| 6 | 12 | Nigel Mansell | Lotus-Renault | 64 | Gearbox | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 2 | Corrado Fabi | Brabham-BMW | 64 | + 3 Laps | 11 | |

| 8 | 14 | Manfred Winkelhock | ATS-BMW | 64 | + 3 Laps | 13 | |

| Ret | 8 | Niki Lauda | McLaren-TAG | 60 | Spun off | 5 | |

| Ret | 7 | Alain Prost | McLaren-TAG | 56 | Puncture | 7 | |

| Ret | 18 | Thierry Boutsen | Arrows-BMW | 55 | Spun off | 20 | |

| Ret | 27 | Michele Alboreto | Ferrari | 54 | Spun off | 9 | |

| Ret | 17 | Marc Surer | Arrows-BMW | 54 | Spun off | 22 | |

| Ret | 19 | Ayrton Senna | Toleman-Hart | 47 | Driveshaft | 6 | |

| Ret | 10 | Jonathan Palmer | RAM-Hart | 46 | Electrical | 25 | |

| Ret | 1 | Nelson Piquet | Brabham-BMW | 45 | Spun off | 12 | |

| Ret | 15 | Patrick Tambay | Renault | 25 | Spun off | 10 | |

| Ret | 20 | Johnny Cecotto | Toleman-Hart | 25 | Spun off | 15 | |

| Ret | 26 | Andrea de Cesaris | Ligier-Renault | 15 | Spun off | 16 | |

| Ret | 21 | Huub Rothengatter | Spirit-Hart | 15 | Fuel leak | 23 | |

| Ret | 22 | Riccardo Patrese | Alfa Romeo | 12 | Spun off | 21 | |

| Ret | 16 | Derek Warwick | Renault | 10 | Spun off | 3 | |

| DSQ | 4 | Stefan Bellof | Tyrrell-Ford | 9 | Disqualified | 17 | |

| Ret | 23 | Eddie Cheever | Alfa Romeo | 8 | Spun off | 14 | |

| Ret | 25 | François Hesnault | Ligier-Renault | 0 | Accident | 19 | |

| DNS | 9 | Philippe Alliot | RAM-Hart | ||||

| DNQ | 3 | Martin Brundle | Tyrrell-Ford | ||||

Source:[9]

| |||||||

Championship standings after the race

edit

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Note: Only the top five positions are included for both sets of standings. Points accurate at final declaration of results. Tyrrell and its drivers were subsequently disqualified and their points reallocated.

Aftermath

editIn a 2022 statement to D Magazine, Waldrop said the July date was chosen to minimize the possibility of rain during the event, and expressed regret that the organizers did not adequately anticipate the effects of Texas summer heat on the event generally and the pavement specifically.[3]

Financial problems and safety concerns led to the 1985 race being cancelled.[11] Race organizer Dallas Grand Prix of Texas Inc., led by local real estate investor Don Walker, had executed a contract with the Formula One Constructors' Association (FOCA) to hold five races in Dallas.[3] Walker clashed with co-organizers and officials and spent money prodigiously. He could not agree with FOCA or Dallas officials on a 1985 race date, and the company would not pay the front money for the second race. Both Walker and Dallas Grand Prix of Texas Inc. ended up in financial distress and were soon under investigation by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation and Securities and Exchange Commission over allegations that Walker had illegally siphoned money from the company to fund his extravagant lifestyle.[12] Co-organizer Larry Waldrop negotiated with Ecclestone in late 1984 in an attempt to bypass Walker and revive the event, but the effort came to naught.[3] The company entered bankruptcy in March 1985, ending any possibility that a follow-on F1 race would take place at Fair Park.[3][12]

Another major obstacle was pushback from residents of the nearby, populous Fair Park neighborhood,[3] which was majority Black and low-income. Dallas city councilwoman Diane Ragsdale told The New York Times that the failure of organizers to consult with neighbors and take noise concerns seriously were part of a historic pattern of "total disrespect for the neighborhood."[13] Ragsdale and the Dallas Black Chamber of Commerce filed a lawsuit against Walker and Dallas Grand Prix of Texas Inc.; in 2022, Waldrop said that it was the main hurdle in his late 1984 FOCA negotiations, because he could not guarantee that authorities would allow the 1985 race to take place.[3] 1984 co-organizer Buddy Boren was eventually able to hold a 1988 Trans-Am Series race at Fair Park after agreeing to donate some race receipts to charity;[14] however, continued noise complaints prompted relocation of the 1989 event to Addison Airport.[15]

References

edit- ^ "Weather information for the "1984 Dallas Grand Prix"". The Old Farmers' Almanac. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Lang, Mike (1992). Grand Prix!: Race-by-race account of Formula 1 World Championship motor racing. Volume 4: 1981 to 1984. Haynes Publishing Group. pp. 259–264. ISBN 0-85429-733-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Arnold, Jon (October 21, 2022). "Remembering the 1984 Dallas Grand Prix, Formula 1's Disastrous Trip to North Texas". dmagazine.com. Dallas, Texas: D Magazine. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

Others were hardly impressed. "We don't normally work in cowshit," notorious FIA chief Bernie Ecclestone was quoted as saying in the Times Herald, complaining about the Fair Park coliseum being repurposed as the garage for the race.

- ^ a b c d Walker, Rob (October 1984). "1st Dallas Grand Prix: Cool Keke". Road & Track: 178–182.

- ^ Schot, Marcel. "A Race to Remember". Atlas F1. 6 (38). Kaizar.Com, Incorporated. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ a b "F1's wildest ever race? – 9 reasons Dallas '84 will never be forgotten". formula1.com. October 21, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ a b "Symonds recalls favourite Senna moment". motorsport.com. April 23, 2004. Archived from the original on February 12, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ Weaver, Paul (April 26, 2014). "Ayrton Senna to be remembered in Imola 20 years after his death". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 12, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ "1984 United States Grand Prix". formula1.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "USA 1984 - Championship • STATS F1". www.statsf1.com. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ David Hayhoe, Formula 1: The Knowledge – 2nd Edition, 2021, page 35.

- ^ a b Arnold, Jon (July 1, 1985). "Grand Prix, Grand Scam, Grand Jury?". dmagazine.com. Dallas, Texas: D Magazine. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ Applebome, Peter (July 8, 1984). "Dallas Seeks Glamour in Grand Prix". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2024.

It shows a total disrespect for the neighborhood, said a black Dallas City Councilwoman, Diane Ragsdale. It's an age-old problem here.

- ^ Lumpkin, Rhae (April 1, 1988). "Grand Prix '88". dmagazine.com. Dallas, Texas: D Magazine. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ Bleakley, Bruce (2017). Addison Airport: Serving Business Aviation for 60 Years, 1957–2017. Dallas, Texas: Brown Books Publishing Group. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-61254-839-5.