2,2,4,4-Tetramethyl-1,3-cyclobutanediol (CBDO) is an aliphatic diol. This diol is produced as a mixture of cis- and trans-isomers, depending on the relative stereochemistry of the hydroxyl groups. It is used as a monomer for the synthesis of polymeric materials, usually as an alternative to bisphenol A (BPA). CBDO is used in the production of tritan copolyester which is used as a BPA-free replacement for polycarbonate.

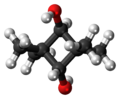

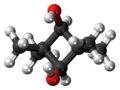

cis- (left) and trans-2,2,4,4-Tetramethyl-1,3-cyclobutanediol (right)

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2,2,4,4-Tetramethylcyclobutane-1,3-diol

| |||

| Other names

1,1,3,3-Tetramethyl-2,4-cyclobutanediol

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.019.219 | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C8H16O2 | |||

| Molar mass | 144.214 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Crystalline white solid (powder) | ||

| Melting point | 126 to 134 °C (259 to 273 °F; 399 to 407 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 210 to 215 °C (410 to 419 °F; 483 to 488 K) | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Flash point | 51 °C (124 °F; 324 K) | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | [1] | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Replacement for BPA

editThe controversies associated with BPA in large quantities are ultimately related to its endocrine disrupting abilities.[1] Like BPA, CBDO is a diol with a structure suitable for making polyesters. CBDO’s C4 ring is sufficiently rigid to prevent the two OH groups from forming cyclic structures. Unlike BPA, there is no current evidence of carcinogenic or toxic effects from CBDO-based consumer products. There are, however, few studies on the toxicology of CBDO for both long term and short term effects.

CBDO has potential advantages relative to BPA as a building block for production of polyesters. CBDO is very stable thermally and mechanically. Polyesters prepared from CBDO are rigid materials, but the combination of CBDO with flexible diols results in materials with high impact resistance, low color, thermal stability, good photooxidative stability and transparency.[2] As an added bonus, CBDO-derived polymers have high ductility.[3] The thermal and mechanical properties of CBDO-derived polyesters are often superior to conventional polyesters.[2]

Preparation

editSynthesis of CBDO involves pyrolysis of isobutyric anhydride followed by hydrogenation of the resulting 2,2,4,4-tetramethylcyclobutanedione.[4] This synthesis resembles the method used to produce CBDO today. The first step involves conversion of the isobutyric acid or its anhydride into the ketene. This ketene then dimerizes to form a four-membered ring with two ketone groups.

The product ring is hydrogenated to give a diol. The last step commonly involves catalytic hydrogenation with ruthenium, nickel, or rhodium catalysts. Hydrogenation of the diketone ring results in both cis and trans isomers.[3][5] A simplified scheme for the production of CBDO is presented below.

Structure and properties

editThe C4 ring of the cis isomer of CBDO is non-planar. For simple non-planar cyclobutanes, dihedral angles range from 19 to 31°. CBDO’s cis isomer crystallizes as two conformers with an average dihedral angle of 17.5° in the solid state.[6] However, the trans isomer has a dihedral angle of 0°.[7]

Polyesterification

editThe current economic method for the production of polyesters is direct esterification of dicarboxylic acids with diols. This condensation polymerization adds monomeric units to a chain. Individual chains react with one another through carboxyl and hydroxyl terminal groups. Finally, transesterification occurs within the chain.[8] Although CBDO is most often used in polyesters, mixed copolycarbonates of CBDO and a series of bisphenols have also been synthesized. The differing reactivities of the cis and trans isomers have not been studied in depth.

References

edit- ^ vom Saal, Frederick S.; Hughes, Claude (August 2005). "An Extensive New Literature Concerning Low-Dose Effects of Bisphenol A Shows the Need for a New Risk Assessment". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (8): 926–933. doi:10.1289/ehp.7713. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1280330. PMID 16079060.

- ^ a b Hoppens, Nathan C.; Hudnall, Todd W.; Foster, Adam; Booth, Chad J. (2004-07-15). "Aliphatic–aromatic copolyesters derived from 2,2,4,4-tetramethyl-1,3-cyclobutanediol". Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 42 (14): 3473–3478. doi:10.1002/pola.20197. ISSN 0887-624X.

- ^ a b Kelsey, Donald R.; Scardino, Betty M.; Grebowicz, Janusz S.; Chuah, Hoe H. (2000-08-01). "High Impact, Amorphous Terephthalate Copolyesters of Rigid 2,2,4,4-Tetramethyl-1,3-cyclobutanediol with Flexible Diols". Macromolecules. 33 (16): 5810–5818. Bibcode:2000MaMol..33.5810K. doi:10.1021/ma000223+. ISSN 0024-9297.

- ^ Wedeking, E.; Weisswange, W. (March 1906). "Ueber die Synthese eines Diketons der Cyclobutanreihe". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 39 (2): 1631–1646. doi:10.1002/cber.19060390287. ISSN 0365-9496.

- ^ W. Theilheimer "1,3-Cyclobutanediols from 1,3-cyclobutandiones" Synthetic Methods of Organic Chemistry, 1962, Volume 16, pp. 29.

- ^ Shirrell, C. D.; Williams, D. E. (1976-06-01). "The crystal and molecular structure of cis -2,2,4,4-tetramethyl-1,3-cyclobutanediol". Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Crystallography and Crystal Chemistry. 32 (6): 1867–1870. Bibcode:1976AcCrB..32.1867S. doi:10.1107/S0567740876006559. ISSN 0567-7408.

- ^ Margulis, T. N. (1969). "Planar cyclobutanes: structure of 2,2,4,4-tetramethyl-cyclobutane-trans-1,3-diol". Journal of the Chemical Society D: Chemical Communications (5): 215–216. doi:10.1039/c29690000215. ISSN 0577-6171.

- ^ Köpnick, Horst; Schmidt, Manfred; Brügging, Wilhelm; Rüter, Jörn; Kaminsky, Walter. "Polyesters". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_227. ISBN 978-3527306732.