From mid-May to mid-June 2019, the republics of India and Pakistan had a severe heat wave. It was one of the hottest and longest heat waves in the subcontinent since the two countries began recording weather reports. The highest temperatures occurred in Churu, Rajasthan, reaching up to 50.8 °C (123.4 °F),[5] a near record high in India, missing the record of 51.0 °C (123.8 °F) set in 2016 by a fraction of a degree.[6] As of 12 June 2019,[update] 32 days are classified as parts of the heatwave, making it the second longest ever recorded.[7]

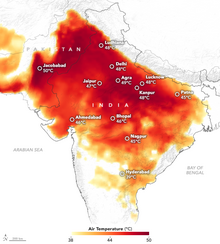

Heat wave affected areas, from the NASA Earth observatory | |

| Type | Heat wave |

|---|---|

| Areas | India Pakistan[1][2][3] |

| Start date | May 2019 |

| End date | June 2019 |

| Losses | |

| Deaths | India: 184 in Bihar, plus dozens more in other states Pakistan: 5[4] |

As a result of hot temperatures and inadequate preparation, more than 184 people died in the state of Bihar,[8] with many more deaths reported in other parts of the country.[9][10] In Pakistan, five infants died after extreme heat exposure.[11]

The heat wave coincided with extreme droughts and water shortages across India and Pakistan. In mid-June, reservoirs that previously supplied Chennai ran dry, depriving millions. The water crisis was exacerbated by high temperatures and lack of preparation, causing protests and fights that sometimes led to killing and stabbing.[12][13][14]

Background

editHeat waves worldwide have become more extreme and more frequent due to human-influenced climate change and global warming.[15][16][17] Since 2004, India and Pakistan have experienced 11 of its 15 warmest recorded years.[18] The frequency and duration of heat waves in India and Pakistan has increased. The Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology has identified several contributing factors, including "El Niño Modoki", an irregular El Niño in which the central Pacific Ocean is warmer than the eastern part, and the loss of tree cover, which reduces shade, increasing temperatures, and reduces moisture in soil, which results in less evapotranspiration and more heat transfer into the atmosphere.[19][20]

In response to the growing number of deaths from heat waves, the Indian government, although not addressing the root causes, began implementing measures intended to save lives in 2013. In Ahmedabad, for example, "school days were reduced, government work programs ceased, and free water was distributed in busy areas." Public gardens were opened during the daytime so that people could seek shade. Professor of public health Parthasarathi Ganguly estimated that 800 fewer people died in 2014 as a result of these policies.[21]

In India, the rainy monsoon season typically begins on 1 June. However, in 2019, the season was delayed by seven days and began on 8 June. When it did occur, the monsoon made slow progress and only brought rains to 10–15% of the country by 19 June. Normally, two-thirds of the country would have received monsoon rains by this time. The lack of rainfall has intensified heat wave conditions and increased water scarcity.[22]

Impact

editThe heat wave has caused multiple deaths and cases of illness. As of 31 May 2019, 8 deaths and 456 cases of illness due to heat were reported in Maharashtra, at least 17 deaths in Telangana, and 3 deaths and 433 cases of heat stroke in Andhra Pradesh.[19] On 10 June 2019, three passengers were found dead on a train as it arrived in Jhansi, apparently due to the extreme heat. A fourth passenger was found in critical condition and brought to a hospital where they died of overheating.[23] In the state of Bihar, heat-related deaths reached 184 on 18 June according to Al Jazeera,[8] while according to Zee News the death toll was 139 on 19 June 2019.[24]

High temperatures have broken or nearly broken records in various cities across India and Pakistan. At one point, 11 of the 15 warmest places in the world were all located in the country.[18] On 2 June 2019, the city of Churu recorded a temperature of 50.8 °C (123.4 °F), only one-fifth of a degree Celsius short of the country's highest-ever temperature, 51 °C (124 °F) during the 2016 heat wave.[6] On 9 June 2019, Allahabad reached 48.9 °C (120.0 °F), breaking its previous all-time record.[18] On 3 and 4 June 2019, the temperature in Jacobabad reached 49 °C (120 °F) making Pakistan's highest-ever temperature.[25] On 10 June 2019, the temperature in Delhi reached 48 °C (118 °F), a new record high for the city in the month of June.[26][27][28] On the same day, peak power usage in Delhi reached 6,686 MW, breaking all previous records.[7] On 29 June 2019, the temperature in Islamabad and Rawalpindi reached 42 °C (108 °F).[2]

The total number of deaths is unknown. For comparison, the 2003 European heat wave killed an estimated 35,000–70,000 people,[29] with temperatures slightly less than in India and Pakistan. In human temperature physiology, core temperatures of 40.0 or 41.5 °C (104.0 or 106.7 °F) are said to be a fever of type hyperpyrexia, and considered a medical emergency as temperature may lead to problems including permanent brain damage, or death.[30]

Water shortages

editDroughts and water shortages have occurred in multiple states and provinces across India and Pakistan,[31] worsening heat wave conditions. In Chennai, millions of people are without consistent access to water. A lack of rainwater and groundwater has left four of the reservoirs that supply the city completely dry. The inability to meet demand for water has forced businesses like hotels and restaurants to close. Water tankers from areas of Tamil Nadu unaffected by drought have been bringing water into some areas of the city. However, government tankers can take up to a month to appear after requested, so some wealthy residents and business owners have opted to pay for costly private water tankers. The poor who live in slums do not have this option; a family in Chennai's slums may receive as little as 30 litres (7.9 US gallons) of water every day compared to an average American household which uses 1,100 litres (290 US gallons) of water a day.[12] In Coimbatore, at least 550 people were arrested for protesting the city's government for mismanaging the water crisis.[13]

Conflicts over access to water have also occurred throughout India. On 7 June, six people were stabbed in Jharkhand during a fight near a water tanker, and one man was killed in a similar fight in Tamil Nadu. In Madhya Pradesh on 5 June, a fight over water led to two men being "seriously injured", while in a separate fight a day earlier, a water tanker driver was "beaten up".[14] In early June, fifteen monkeys were found dead in a forest in Madhya Pradesh, possibly as a result of the heat wave. Veterinarian Arun Mishra says this may have happened due to a conflict over water with a larger group of 30–35 monkeys. Mishra said this was "rare and strange" because herbivores do not usually engage in such conflicts.[32]

Bihar encephalitis outbreak

editThe heat wave is a possible aggravating factor in an encephalitis outbreak in Bihar which has killed over 100 children since 1 June.[33][34]

Responses

editThe Indian National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) had a goal for keeping heat related deaths this year to single digits. In 2018, the heat wave death toll was kept at 20 through public safety measures; for example, government workers across the country conducted awareness campaigns and distributed free water. However in 2019, the national general election took place and workers who normally issued heat wave warnings were instead performing election duties.[35]

In early June, the Indian Meteorological Department issued a severe heat wave warning in Rajasthan and nearby areas such as Delhi.[6] The Ministry of Health advised avoiding the sun between noon and 3 p.m. and not drinking alcohol, tea, or coffee. Meanwhile the NDMA recommended covering the head, cross-ventilating rooms, and sleeping under a slightly wet sheet.[36]

Asphalt used for roads expectantly begins to melt at 50 °C (122 °F); therefore, on 3 June, the government of Churu poured water onto roads in order to cool them and prevent them from melting.[37]

In response to fights over water in Madhya Pradesh, the police were deployed to guard water tankers and other sources of water from rioters, beginning 8 June.[14]

On 17 June, the government of Gaya, a city in Bihar, imposed Section 144 to be active, which empowers an executive magistrate to prohibit an assembly of more than four persons in an area, and banned construction work and assemblies between 11 a.m. and 4 p.m.[24]

The Pakistan Medical Association urged people to learn about the measures to avoid heat-related deaths.[38]

References

edit- ^ Leister, Eric. "Temperatures pass 50 C as grueling India heat wave enters 2nd week with no end in sight". Accuweather.

- ^ a b "Heatwave hits Pakistan as temperature reaches 42 degrees Celsius - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Pakistan sizzles under intense heat | Pakistan Today". www.pakistantoday.com.pk.

- ^ "Pakistan Infants death update: Five infants confirmed dead in Pakistan as hospital air conditioning unit breaks down". gulfnews.com. 2 June 2019.

- ^ "India reels as summer temperatures touch 50C". BBC News. 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Kahn, Brian (3 June 2019). "It Hit 123 °F (51 °C) in India This Weekend". Earther. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ a b Chauhan, Chetan (12 June 2019). "India staring at longest heatwave in 3 decades". MSN. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ a b "India's heatwave turns deadly". Al Jazeera. 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Srivastava, Roli (12 June 2019). "India heatwave deaths rise to 36, poorest workers worst hit". Reuters. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ "Nitish Kumar Cancels Aerial Inspection of Heat Wave Affected Areas, to Visit Hospital in Gaya". India.Com. 20 June 2019. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Pakistan Infants death update: Five infants confirmed dead in Pakistan as hospital air conditioning unit breaks down". gulfnews.com. 2 June 2019.

- ^ a b Yeung, Jessie (19 June 2019). "India's sixth biggest city is almost entirely out of water". CNN. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ a b Yeung, Jessie; Gupta, Swati (20 June 2019). "More than 500 arrested after protests and clashes as India water crisis worsens". CNN. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Janjevic, Darko (8 June 2019). "India heat wave triggers clashes over water". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Samenow, Jason (11 June 2019). "Planet is entering 'new climate regime' with 'extraordinary' heat waves intensified by global warming, study says". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Miller, Brandon (27 July 2018). "Deadly heat waves becoming more common due to climate change". CNN. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Lindsey, Rebecca (2 April 2018). "Influence of global warming on U.S. heat waves may be felt first in the West and Great Lakes regions". Climate.gov. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ a b c "India likely to witness its worst summer ever, temperatures will remain severe for a long time". Business Insider India. 12 June 2019. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Heat Takes Heavy Toll Across India". The Weather Channel. 31 May 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Study Shows Increase in Heatwave Conditions from Next Year". The Weather Channel. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Safi, Michael (2 June 2018). "India slashes heatwave death toll with series of low-cost measures". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "As Monsoon Makes Slowest Progress in 12 Years, Rain Deficit Crosses 44%". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Chauhan, Arvind (11 June 2019). "Four Kerala Express passengers die due to heat in Jhansi". The Times of India. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Heatwave claims lives of 139 people in Bihar". Zee News. 19 June 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Leister, Eric (6 June 2019). "Temperatures pass 50 C as grueling India heat wave enters 2nd week with no end in sight". www.accuweather.com. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Mishra, Himanshu (10 June 2019). "Delhi at 48 Degrees, Highest Ever in June As Heat Wave Sweeps North India". NDTV. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Delhi records highest temperature in history". Khaleej Times. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Delhi records all-time high of 48 degrees Celsius in June, heatwave to continue". The Times of India. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Peer-reviewed analysis places the European death toll at more than 70,000" (from article) Robine, Jean-Marie; Cheung, Siu Lan K.; Le Roy, Sophie; Van Oyen, Herman; Griffiths, Clare; Michel, Jean-Pierre; Herrmann, François Richard (2008). "Solongo". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 331 (2): 171–178. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2007.12.001. ISSN 1631-0691. PMID 18241810.

- ^ McGugan EA (March 2001). "Hyperpyrexia in the emergency department". Emergency Medicine. 13 (1): 116–20. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2026.2001.00189.x. PMID 11476402.

- ^ "Country's water woes may worsen". Gulf-Times. 1 July 2019.

- ^ Embury-Dennis, Tom (8 June 2019). "India heatwave: Desperation for water thought to have made 15 monkeys kill each other". The Independent. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "Heat, lack of nutrition, awareness add to AES, Bihar kids toll over 100". The Indian Express. Indian Express Group. 18 June 2019. OCLC 70274541. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "Litchi Toxins, Malnutrition or Heat Wave? Doctors Explain What's Causing Deadly AES Epidemic in Bihar". News18. 18 June 2019. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Mashal, Mujib (13 June 2019). "India Heat Wave, Soaring Up to 123 Degrees, Has Killed at Least 36". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Slater, Joanna (5 June 2019). "'It is horrid': India roasts under heat wave with temperatures above 120 degrees". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Dasgupta, Shounak (3 June 2019). "World's 15 hottest places are in India, Pakistan as pre-monsoon heat builds". Reuters. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "PMA issues guideline for people to avoid heat-wave". 17 June 2019. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.