The 766th Independent Infantry Regiment (Korean: 제766독립보병련대) was an elite light infantry unit of North Korea's Korean People's Army (KPA) that existed briefly during the Korean War. It was headquartered in Hoeryong, North Korea, and was also known as the 766th Unit (Korean: 766부대). Trained extensively in amphibious warfare and unconventional warfare, the 766th Regiment was considered a commando unit. The regiment was trained to conduct assaults by sea and then to lead other North Korean units on offensive operations, to infiltrate behind enemy lines, and to disrupt enemy supplies and communications.

| 766th Independent Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

| Korean: 제766독립보병련대 | |

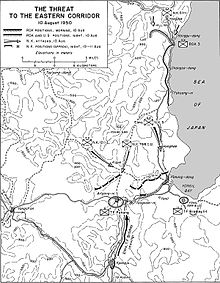

Map of the 766th Independent Infantry Regiment's final offensive action, August 10, 1950 | |

| Active | April 1949 – August 19, 1950 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Commando |

| Role | Amphibious warfare Close-quarters combat Direct action Forward observer Irregular warfare Mountain warfare Raiding Reconnaissance Unconventional warfare Urban warfare |

| Size | Regiment |

| Part of | |

| Garrison/HQ | Hoeryong, North Korea |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Senior Colonel Oh Jin Woo |

Activated in 1949, the regiment trained for more than a year before the outbreak of the war on June 25, 1950. On that day, half of the regiment led North Korean forces against South Korean troops by land and sea, pushing them back after several days of fighting. Over the next six weeks, the regiment advanced slowly down the Korean Peninsula, acting as a forward unit of the North Korean army. Suffering from a lack of supplies and mounting casualties, the regiment was committed to the Battle of Pusan Perimeter as part of a push to force United Nations (UN) troops out of Korea.

The regiment saw its final action at the Battle of P'ohang-dong, fighting unsuccessfully to take the town from U.N. troops. Racked by U.N. naval and air forces and suffering extensive losses from continuous fighting, the regiment was forced to retreat from the P'ohang-dong battlefield. It moved north, joining a concentration of other KPA units, before being disbanded and absorbed into the KPA's 12th Division.

Organization

editUpon creation, the 766th Unit was designed to vary in size, consisting of a number of smaller units capable of acting alone.[1] Eventually, it was reinforced to the size of a full regiment, with 3,000 men equally distributed across six battalions (numbered 1st through 6th). It was made directly subordinate to the KPA Army headquarters[2] and put under the command of Senior Colonel Oh Jin Woo, who would command the unit for its entire existence.[3] All 500 men of the 3rd Battalion were lost just before the war started when their transport was sunk while attacking Pusan harbor by the Republic of Korea Navy.[4][5] For the remainder of its existence the regiment was whittled down by losses until it numbered no more than 1,500 men and could not muster more than three battalions.[6]

History

editOrigins

editDuring the planning for the invasion of South Korea in the years before the war, the North Korean leadership began to create large numbers of commando and special forces units to send south. These units subverted South Korean authority before and during the war with terror campaigns, sabotage and inducing rebellions in ROK military units. Hundreds of commandos were sent to South Korea in this fashion, and by the end of the war up to 3,000 of them had been trained and armed.[7] During this time, North Korean leadership also ordered the creation of large conventional units to act as advance forces for the actual invasion. The 766th Unit was formed in April 1949 at the Third Military Academy in Hoeryong, North Korea. The academy was specially designed to train commandos, and the 766th was originally designed to supervise North Korean light infantry ranger units.[1] Over the next year, the 766th Unit received extensive training in unconventional warfare and amphibious warfare.[7] During this time, the unit was expanded in size to 3,000 men in six battalions.[2]

Prior to the beginning of the war in June 1950, the 766th completed training and was moved to the front at Yangyang to support the KPA's 5th Division.[8] The North Korean plan was to conduct amphibious landings in Chongdongjin and Imwonjin on the eastern coast using the 766th Regiment, in conjunction with the 549th Unit. These amphibious landings would harass the rear area of the Republic of Korea Army, providing supporting attacks to the planned frontal attack by the KPA's II Corps directly from the north.[9] The 766th was in position by June 23 and prepared for the attack.[10] The unit was moved to the ports of Wonsan and Kansong and loaded into ships.[11] With the 3,000 men in the 766th, another 3,000 in the 549th, and 11,000 men in the KPA's 5th Division, the 17,000 North Korean troops outnumbered the Republic of Korea Army's (ROK) 8th Division's 6,866 by a ratio of 2.1 to 1.[2] The combination of the frontal attack and the landings were expected to crush the ROK division and prevent reinforcements from moving in to support it.[12]

The regiment was split into three groups for the attack. Three battalions acted as spearheads for the 5th Division on land while two more battalions conducted the landings in Imwonjin.[13] This 2,500 man force reassembled and then led the North Korean units south.[4] In the meantime, the 3rd Battalion, 766th Regiment was detached and sent on a mission to infiltrate Pusan.[13] Paired with additional support, it formed the 600-man 588th Unit.[14] 588th Unit was tasked with raiding Pusan harbor, destroying vital facilities to make it impossible for UN forces to land troops there.[15] However, the troop transport carrying the 588th Unit was discovered and sunk by United Nations ships outside Pusan harbor the morning of June 25, destroying the 3rd Battalion.[5]

Landing at Imwonjin

editAround 04:00 on June 25, NK 5th Division attacked ROK 10th Regiment's forward positions.[16] Three hours later, the 766th Regiment landed two battalions using motor and sail boatsat the village of Imwonjin. Villagers were used to organize supplies. One battalion headed into the T'aebaek Mountains and the other advanced north toward Samcheok. The ROK 8th Division, under attack from the front and rear, requested reinforcements but the general North Korean offensive along the 38th parallel[17] meant there were none.

The ROK 21st Regiment, 8th Division's southernmost unit, moved to counter the amphibious attack. The regiment's 1st Battalion moved from Bukp'yong into the Okgye area; it, with local police and militia forces, ambushed forward elements of the 766th, and drove back the 766th Regiment's northern advance.[18] Another 766th Regiment battalion took Bamjae and blocked one of the 8th Division's main supply routes.[19] A moderately effective civilian militia reinforced ROK troops.[14] The ROK 8th Division withdrew on June 27 under pressure from the attacks and breakdowns in communication. The ROK eastern flank was forced back as the ROK 6th Division also retreated.[20] The 766th Regiment had established a bridgehead and disrupted communications in the initial attack.[21]

Advance

editWith the ROK army in retreat, the 766th Regiment, 549th Unit, and KPA's 5th Divisions all advanced steadily south along the eastern roads without encountering much resistance.[22][23] Across the entire front the North Korean Army had successfully routed the South Koreans and was pushing them south.[16] The 766th Regiment acted as an advance force, attempting to infiltrate further inland as it moved through the mountainous eastern region of the country.[24] The rugged terrain of the eastern regions of Korea, poor communication equipment, and unreliable resupply lines thwarted the South Korean resistance. The North Koreans used this to their advantage in advancing but they began to experience the same problems themselves.[22] The 5th Division and the two other units began advancing south slowly and cautiously, sending strong reconnaissance parties into the mountains to ensure they would not be threatened from the rear. However, this more cautious advance began to give the South Koreans valuable time to build up further south.[25] By June 28, the 766th had infiltrated into Taebaek-san from Uljin and was moving toward Ilwolsan, Yongyang and Cheongsong in order to block communications between Daegu and Busan, where United States Army forces were landing in an attempt to support the collapsing ROK Army.[3]

The ROK 23rd Regiment of the ROK 3rd Division was moved to block the advance of the three units at Uljin. The ROK forces mounted a series of delaying actions against the main North Korean force, which was significantly dispersed throughout the mountainous region and unable to muster its overwhelming strength. The ROK regiment was subsequently able to hold up the North Korean advance until July 5.[26] On July 10, the 766th separated from the 5th Division and met an advance party of North Korean civilians in Uljin who had been sent to set up a government in the area. From here, the 766th dispersed in small groups into the mountains.[25] On July 13 it reached Pyonghae-ri, 25 miles (40 km) north of Yongdok.[23]

Over the next week, the 766th Regiment and the KPA's 5th Division continued in slow advance south as it met increasing South Korean resistance. United Nations air support began to increase, slowing the advance further. The force continued to occupy the eastern flank, and by July 24 it was advancing from the Chongsong-Andong region and approaching Pohang. On its flank was the KPA's 12th Division.[27] Progress halted as UN aerial and naval bombardment made movement more difficult. At the same time, the North Korean units' supply lines were stretched thin and began to break down, forcing them to conscript South Korean civilians to carry supplies.[28]

Resistance

editOn July 17, the KPA's 5th Division entered Yongdok, taking the city without much resistance before fierce UN air attacks caused the division heavy losses. Still, it was able to surround the ROK 3rd Division in the city. By now, the 5th Division and the 766th Regiment had been reduced to a combined strength of 7,500 men to the ROK 3rd Divisions' 6,469.[29][30] The 766th massed its force again to assist the 5th Division in surrounding and besieging the ROK 3rd Division, which was trapped in the city.[31] The 3rd Division, in the meantime, was ordered to remain in the city to delay the North Koreans as long as possible. It was eventually evacuated by sea after delaying North Korean forces for a considerable time.[32] The rugged terrain of the mountains prevented the North Korean forces from conducting the enveloping maneuvers they had used so effectively against other troops, and their advantages in numbers and equipment had been negated in the fight.[33]

By July 28, the division was still embroiled in this fight and the 766th bypassed it and moved toward Chinbo on the left flank of the city.[34] However the 766th had suffered significant setbacks at Yongdok, with substantial losses due to American and British naval artillery fire.[33] Once it arrived in the area, it met heavier resistance from South Korean police and militia operating in armored vehicles. With air support, they offered the heaviest resistance the unit had faced thus far. With the support of only one of the 5th Division's regiments, the 766th was unable to sustain its advance and had to pull back by the 29th.[34] Movement from the ROK Capital Division prevented the 766th Regiment from infiltrating further into the mountains.[35] ROK cavalry and civilian police then began isolated counteroffensives against the 766th.[36] These forces included special counter-guerrilla units targeting the 766th and countering its tactics.[37] South Korean troops halted the advance of the North Koreans again around the end of the month thanks to increased reinforcements and support closer to the Pusan Perimeter logistics network.[36]

On August 5, the KPA's 12th Division pushed back the ROK Capital Division in the Ch'ongsong-Kigye area and linked up with elements of the 766th which had infiltrated the area of Pohyunsan. Unopposed, they began to prepare to attack P'ohang to secure entry into the UN's newly established Pusan Perimeter.[38] The Regiment was ordered to begin an attack in coordination with the KPA's 5th Division. The Korean People's Army planned simultaneous offensives across the entire Perimeter,[31] including a flanking maneuver by the 766th and the 5th Division to envelop UN troops and push them back to Pusan.[39] The 766th was not reinforced; North Korean planners intended it to move unseen around the UN lines while the majority of the UN and North Korean troops were locked in fighting around Taegu and the Naktong Bulge.[30]

By this time, however, North Korean logistics had been stretched to their limit, and resupply became increasingly difficult.[40] By the beginning of August, the North Korean units operating in the area were getting little to no food and ammunition supply, instead relying on captured UN weapons and foraging for what they could find. They were also exhausted from over a month of advancing, though morale remained high among the 766th troops.[41] The 766th Regiment specialized in raiding UN supply lines, and effectively mounted small disruptive attacks against UN targets to equip themselves.[42]

Disbandment

editAt dawn on August 11, one 300-man battalion[43] of the 766th Regiment entered the village of P'ohang, creating a state of alarm among its populace.[40] The village was only protected by a small force of South Korean Navy, Air Force and Army personnel comprising the rear guard of the ROK 3rd Division. The South Korean forces engaged the 766th forces around the village's middle school with small-arms fire until noon. At that point, North Korean armored vehicles moved in to reinforce the 766th troops and drove the South Koreans out of the village.[44]

The village was strategically important because it was one of the few direct routes through the mountains and into the Gyeongsang plain. It also led directly to the land routes being used by the UN to reinforce Taegu.[45] Upon hearing of the fall of P'ohang, UN Eighth United States Army commander Lieutenant General Walton Walker immediately ordered naval and air bombardment of the village. He also ordered ROK and US forces to secure regions around the village to prevent the further advance of the North Korean troops.[44] Within a few hours, the village was being blasted by artillery forcing the Regiment's advance force to pull back.[43] The 766th's forces congregated and fought in the hills around the village.[40] They joined elements of the KPA's 5th Division, and did not enter P'ohang until night.[43]

UN forces responded to the threat with overwhelming numbers. A large force of South Korean troops, designated Task Force P'ohang, was massed and sent into P'ohang-dong to engage the 766th Regiment and the 5th Division.[46] ROK troops attacked toward An'gang-ni to the east, forcing the KPA's 12th Division into a full retreat. Threatened with encirclement, the KPA's 5th Division and 766th Regiment were ordered into full retreat on August 17. By this time, the 766th had been reduced to 1,500 men, half its original strength.[6]

Exhausted and out of supplies, the 766th Regiment moved to Pihak-san, a mountain 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Kigye, to join the shattered KPA's 12th Division. The 12th Division was reduced to 1,500 men in the fighting, and 2,000 army replacements and South Korean conscripts were brought to replenish the division. The 766th Regiment was also ordered to merge its remaining troops into the depleted KPA's 12th Division. Upon the completion of the merger with the 12th Division on August 19, 1950, the 766th Regiment ceased to exist. It had trained for close to 14 months prior to the war but fought for less than two.[6][47]

See also

edit- 71: Into the Fire, a 2010 South Korean war film based on the battle of P'ohang-dong

- 78th Independent Infantry Regiment

Notes

edit- ^ a b Millett 2000, p. 49

- ^ a b c Millett 2000, p. 147

- ^ a b Millett 2000, p. 336

- ^ a b Rottman 2001, p. 167

- ^ a b Rottman 2001, p. 171

- ^ a b c Appleman 1998, p. 332

- ^ a b Millett 2000, p. 52

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 27

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 118

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 125

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 124

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 209

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 28

- ^ a b Millett 2010, p. 91

- ^ Millett 2010, p. 92

- ^ a b Alexander 2003, p. 52

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 210

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 212

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 213

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 218

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 411

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 105

- ^ a b Alexander 2003, p. 74

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 275

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 106

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 340

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 392

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 396

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 439

- ^ a b Alexander 2003, p. 109

- ^ a b Appleman 1998, p. 255

- ^ Millett 2010, p. 199

- ^ a b Alexander 2003, p. 116

- ^ a b Millett 2000, p. 400

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 401

- ^ a b Millett 2010, p. 200

- ^ Millett 2010, p. 194

- ^ Millett 2000, p. 493

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 108

- ^ a b c Alexander 2003, p. 135

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 333

- ^ Millett 2010, p. 164

- ^ a b c Appleman 1998, p. 327

- ^ a b Millett 2000, p. 497

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 320

- ^ Appleman 1998, p. 331

- ^ Rottman 2001, p. 166

References

edit- Alexander, Bevin (2003), Korea: The First War We Lost, New York City, New York: Hippocrene Books, ISBN 978-0-7818-1019-7

- Appleman, Roy E. (1998), South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War, Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0, archived from the original on 2013-11-02, retrieved 2010-12-22

- Millett, Allan R. (2000), The Korean War, Volume 1, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-7794-6

- Millett, Allan R. (2010), The War for Korea, 1950–1951: They Came from the North, Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 978-0-7006-1709-8

- Rottman, Gordon (2001), Korean War Order of Battle: United States, United Nations, and Communist Ground, Naval, and Air Forces, 1950–1953, Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers, ISBN 978-0-275-97835-8