The Mitsubishi A5M, formal Japanese Navy designation Mitsubishi Navy Type 96 Carrier-based Fighter (九六式艦上戦闘機), experimental Navy designation Mitsubishi Navy Experimental 9-Shi Carrier Fighter, company designation Mitsubishi Ka-14, was a WWII-era Japanese carrier-based fighter aircraft. The Type number is from the last two digits of the Japanese imperial year 2596 (1936) when it entered service with the Imperial Navy.

| A5M | |

|---|---|

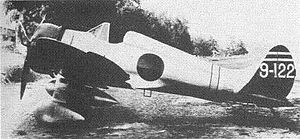

An A5M2b with arrestor hook and drop tank | |

| General information | |

| Type | Carrier-based fighter |

| Manufacturer | Mitsubishi Heavy Industries |

| Designer | |

| Primary user | Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service |

| Number built | 1,094 |

| History | |

| Introduction date | 1936 |

| First flight | 4 February 1935 |

| Retired | 1945 |

| Variants | |

It was the world's first low-wing monoplane shipboard fighter to enter service[note 1] and the predecessor of the famous Mitsubishi A6M "Zero". The Allied reporting name was Claude.

Design and development

editIn 1934, the Imperial Japanese Navy prepared a specification for an advanced fighter, requiring a maximum speed of 350 km/h (220 mph) at 3,000 m (9,800 ft) and able to climb to 5,000 m (16,000 ft) in 6.5 minutes.[1] This 9-shi (1934) specification produced designs from both Mitsubishi and Nakajima.[2][3]

Mitsubishi assigned the task of designing the new fighter to a team led by Jiro Horikoshi (original creator of the similar but unsuccessful Mitsubishi 1MF10, and later responsible for the famous A6M Zero).[4] The resulting design, designated Ka-14 by Mitsubishi, was an all-metal low-wing fighter, with a thin elliptical inverted gull wing and a fixed undercarriage, which was chosen as the increase in performance (estimated as 10% in drag, but only a mere 3% increase in maximum speed) arising from use of a retractable undercarriage was not felt to justify the extra weight.[5][6] The first prototype, powered by a 447 kW (600 hp) Nakajima Kotobuki 5 radial engine, flew on 4 February 1935.[7] The aircraft far exceeded the requirements of the specification, with a maximum speed of 450 km/h (280 mph) being reached.[4] The second prototype was fitted with a revised, ungulled wing, and after various changes to maximize maneuverability and reduce drag, was ordered into production as the A5M.

With the Ka-14 demonstrating excellent performance, the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force ordered a single modified prototype for evaluation as the Ki-18. While this demonstrated similar performance to the Navy aircraft and hence was far faster than the IJAAF's current fighter, the Kawasaki Ki-10 biplane, the type was rejected by the army owing to its reduced maneuverability.[8] The Army then produced a specification for an improved advanced fighter to replace the Ki-10. Mitsubishi, busy turning the Ka-14 into the A5M, submitted a minimally changed aircraft as the Ki-33, this being defeated by Nakajima's competing aircraft, which was ordered into service as the Ki-27.[9]

Operational history

editThe aircraft entered service in early 1937, and soon saw action in aerial battles at the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War,[10] including air-to-air battles with the Republic of China Air Force's Boeing P-26C Model 281 "Peashooters" in the world's first aerial dogfighting and kills between monoplane fighters built of mostly metal.[11] The A5M replaced the Nakajima A4N1 in service, a biplane fighter aircraft.[12]

Chinese Nationalist pilots, primarily flying the Curtiss Hawk III, fought against the Japanese, but the A5M was the better of almost every fighter aircraft it encountered. Though armed with only a pair of 7.7 mm (0.303 in) machine-guns, the new fighter proved effective and damage-tolerant, with excellent manoeuvrability and robust construction.[13] Later on A5M's also provided much-needed escorts for the then-modern but vulnerable Mitsubishi G3M bombers.

The Mitsubishi team continued to improve the A5M, working through versions until the final A5M4, which carried an external underside drop tank to provide fuel for extended range.

The A5M's most competitive adversary in the air was the Polikarpov I-16, a fast and heavily armed fighter flown by both Chinese Air Force regulars and Soviet volunteers. Air battles in 1938, especially on 18 February and 29 April, ranked among the largest air battles ever fought at the time. The battle of 29 April saw 67 Polikarpov fighters (31 I-16s and 36 I-15 bis) against 18 G3Ms escorted by 27 A5Ms. Each side claimed victory: the Chinese/Soviet side claimed 21 Japanese aircraft (11 fighters and 10 bombers) shot down with 50 Japanese airmen killed and two captured having bailed out while losing 12 aircraft and 5 pilots killed; the Japanese claimed they lost only two G3Ms and two A5Ms shot down with over 40 Chinese aircraft shot down.[14]

104 A5M aircraft were modified to accommodate a two-seater cockpit. This version, used for pilot training, was dubbed the A5M4-K. K version aircraft continued to be used for pilot training long after standard A5Ms left front-line service.

Almost all A5Ms had open cockpits. A closed cockpit was tried but found little favor among Navy aviators[citation needed]. All had fixed, non-retractable undercarriage. Wheel spats were a feature of standard fighters but not training aircraft.

The Flying Tigers encountered the Type 96, although not officially, and one was shot down at Mingaladon airfield, Burma on 29 January 1942.[15]

Some A5Ms remained in service at the end of 1941 when the United States entered World War II in the Pacific. US intelligence sources believed the A5M still served as Japan's primary Navy fighter, when in fact the A6M Zero had replaced it on first-line aircraft carriers and with the Tainan Kōkūtai in Taiwan. Other Japanese carriers and Kōkūtai (air groups) continued to use the A5M until production of the Zero caught up with demand. On 1 February 1942, the US carrier USS Enterprise launched air strikes at Japanese air and naval bases on Roi and Kwajalein Atolls in the Marshall Islands. During these actions, Mitsubishi A5Ms shot down three Douglas SBD dive bombers, including the aircraft of LtCdr. Halstead Hopping, commanding officer of VS-6 Squadron.[16] The last combat actions with the A5M as a fighter took place at the Battle of the Coral Sea on 7 May 1942, when two A5Ms and four A6Ms of the Japanese carrier Shōhō fought against US aircraft that sank their carrier.[17]

In the closing months of the war most remaining A5M airframes were used for kamikaze attacks.

Variants

editData from Januszewski [18]

- Ka-14

- Six prototypes with various engines and design modifications.

- A5M1

- Navy carrier-based fighter, Model 1 : first production model with 633 kW (850 hp) Kotobuki 2 KAI I engine.

- A5M2/2a

- Model 21: More powerful engine.

- A5M2b

- Model 22: First production examples with NACA cowling and 477 kW (640 hp) Kotobuki 3 engine.

- A5M3a

- Prototypes with 448 kW (601 hp) Hispano-Suiza 12 Xcrs engine.

- A5M4

- Model 24 (ex-Model 4): The A5M2b with different engine, closed cockpit, additional detachable Drop tank. The last production models (Model 34) with Kotobuki 41 KAI engine.

- A5M1-A5M4

- 780 constructed by Mitsubishi. 39 constructed by Watanabe, 161 manufactured by Naval Ohmura Arsenal.

- A5M4-K

- Two-seat trainer version of A5M4, 103 constructed by Naval Ohmura Arsenal.

- Ki-18

- Single prototype land-based version for IJAAF, based on the A5M. 410 kW (550 hp) Kotobuki 5 engine.

- Ki-33

- Two prototypes, a development of Ki-18 with a different engine, and closed cockpit.

- Total production (all variants): 1,094

Operators

editData from[19]

- Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service

- Aircraft carrier Akagi

- Aircraft carrier Hōshō

- Aircraft carrier Kaga

- Aircraft carrier Ryūjō

- Aircraft carrier Shōhō

- Aircraft carrier Sōryū

- Aircraft carrier Zuihō

- Chitose Kōkūtai

- Oita Kōkūtai

- Ōminato Kōkūtai

- Omura Kōkūtai

- Sasebo Kōkūtai

- Tainan Kōkūtai

- Yokosuka Kōkūtai

- 12 Air Corps

- 13 Air Corps

- 14 Air Corps

- 15 Air Corps

Surviving aircraft

editNo restored or airworthy A5Ms are known to be in existence. The one A5M known to exist is a disassembled one underwater in the sunken ship Fujikawa Maru in Chuuk Lagoon in Micronesia, along with a number of disassembled Mitsubishi A6M Zeros.

Specifications (Mitsubishi A5M4)

editData from Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War[20]and The Concise Guide to Axis Aircraft of World War II [21]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 7.565 m (24 ft 10 in)

- Wingspan: 11 m (36 ft 1 in)

- Height: 3.27 m (10 ft 9 in)

- Wing area: 17.8 m2 (192 sq ft)

- Airfoil: root: B-9 mod. (16%); tip: B-9 mod. (9%)[22]

- Empty weight: 1,216 kg (2,681 lb)

- Gross weight: 1,671 kg (3,684 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Nakajima Kotobuki 41 or 41 KAI 9-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engine, 530 kW (710 hp) for take-off

- 585 kW (785 hp) at 3,000 m (9,800 ft)

- Propellers: 3-bladed metal propeller

Performance

- Maximum speed: 435 km/h (270 mph, 235 kn) at 3,000 m (9,800 ft)

- Range: 1,201 km (746 mi, 648 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 9,800 m (32,200 ft)

- Time to altitude: 3,000 m (9,800 ft) in 3 minutes 35 seconds

- Wing loading: 93.8 kg/m2 (19.2 lb/sq ft)

- Power/mass: 0.316 kW/kg (0.192 hp/lb)

Armament

- Guns: 2× 7.7 mm (0.303 in) Type 97 aircraft machine gun fuselage-mounted synchronized machine guns firing through the engine cylinders and propeller at about 1 and 11 o'clock.

- Bombs:

- 2x 30 kg (66 lb) Type 99 high-explosive bombs or

- 1x 160 L (42.27 US gal; 35.20 imp gal) drop-tank

See also

editAircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

editNotes

edit- ^ It was however preceded by the Dewoitine D.1ter and Wibault Wib.74 high wing monoplanes into service

Citations

edit- ^ Green & Swanborough 1982, p. 27

- ^ Mikesh & Abe 1990, p. 234

- ^ Januszewski 2003, p. 6

- ^ a b Mikesh & Abe 1990, p. 173

- ^ Green & Swanborough 1982, p. 28

- ^ Januszewski 2003, p. 8

- ^ Green & Swanborough 1982, p. 29

- ^ Green & Swanborough 1982, p. 31

- ^ Mikesh & Abe 1990, pp. 187–188

- ^ Sakaida 1998, p. 8.

- ^ Sino-Japanese Air War 1937 – 1945 via http://surfcity.kund.dalnet.se

- ^ Dmitriy Khazanov, Aleksander Medved, Edward M. Young, Tony Holmes (2019). Air Combat: Dogfights of World War II. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 102.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ War machines, Aerospace Publishing/Orbis Publishing, 1983, Italian edition, p.1168

- ^ Air battles over China, 1938 via http://surfcity.kund.dalnet.se

- ^ Bond & Anderson 1984, pp. 86, 88

- ^ Tillman, Barrett. SBD Dauntless Units of World War 2. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012. p16

- ^ Januszewski 2003, p. 47

- ^ Januszewski 2003, p. 52

- ^ Januszewski 2003, p. 49.

- ^ Francillon, René J. (1979). Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War. London: Putnam & Company Limited. pp. 342–349. ISBN 0-370-30251-6.

- ^ Mondey 1996, p. 193.

- ^ Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

edit- Bond, Charles R.; Anderson, Terry H. (1984). A Flying Tiger's Diary. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University. ISBN 0-89096-408-4.

- Francillon, Ph.D., René J. Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War. London: Putnam & Company Ltd., 1970 (second edition 1979). ISBN 0-370-30251-6

- Green, William (1961). Warplanes of the Second World War, Volume Three: Fighters. London: Macdonald & Co. (Publishers) Ltd. ISBN 0-356-01447-9.

- Green, William; Swanborough, Gordon (August–November 1982). "The Zero Precursor...Mitsubishi's A5M". Air Enthusiast. No. 19. pp. 26–43.

- Januszewski, Tadeusz (2003). Mitsubishi A5M Claude. Sandomierz, Poland/Redbourn, UK: Mushroom Model Publications. ISBN 83-917178-0-1.

- Mikesh, Robert C.; Abe, Shorzoe (1990). Japanese Aircraft, 1910-1941. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books. ISBN 0-85177-840-2.

- Mondey, David, ed. (1996). The Concise Guide to Axis Aircraft of World War II. London: Chancellor. ISBN 1-85152-966-7.

- Sakaida, Henry (1998). Imperial Japanese Navy Aces, 1937-45. Botley, Oxfordshire, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-727-9.

- Unknown. "Handbook of Japanese Aircraft 1910-1945 (Model Art Special #327)" Model Art Modeling Magazine, March 1989.

- Unknown. Mitsubishi Type 96 Carrier Fighter/Nakajima Ki-27 (The Maru Mechanic #49). Tokyo: Kojinsha Publishing, 1984.

- Unknown. Type 96 Carrier Fighter (Famous Airplanes of the World #27). Tokyo: Bunrindo Publishing, 1991.