The AD–AS or aggregate demand–aggregate supply model (also known as the aggregate supply–aggregate demand or AS–AD model) is a widely used macroeconomic model that explains short-run and long-run economic changes through the relationship of aggregate demand (AD) and aggregate supply (AS) in a diagram. It coexists in an older and static version depicting the two variables output and price level, and in a newer dynamic version showing output and inflation (i.e. the change in the price level over time, which is usually of more direct interest).

The AD–AS model was invented around 1950 and became one of the primary simplified representations of macroeconomic issues toward the end of the 1970s when inflation became an important political issue. From around 2000 the modified version of a dynamic AD–AS model, incorporating contemporary monetary policy strategies focusing on inflation targeting and using the interest rate as a primary policy instrument, was developed, gradually superseding the traditional static model version in university-level economics textbooks.

The dynamic AD–AS model can be viewed as a simplified version of the more advanced and complex dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models which are state-of-the-art models used by central banks and other organizations to analyze economic fluctuations. Unlike DSGE models, the dynamic AD–AS model does not provide a microeconomic foundation in the form of optimizing firms and households, but the macroeconomic relationships ultimately posited by the optimizing models are similar to those emerging from the modern-version AD–AS model. At the same time, the latter is much simpler and consequently more easily accessible for students, making it a widespread tool for teaching purposes.

History

editOrigins

editAccording to economic historian A.K. Dutt, the AD–AS diagram first made its appearance in 1948 in a contribution by O.H. Brownlee to a textbook on applied economics. Also a textbook by Kenneth E. Boulding in the same year presented a diagram in output-price space, but unlike Brownlee's version without trying to solve the model; Boulding rather uses the diagram to warn about the dangers of aggregative thinking. Brownlee, on the contrary, went on working on the diagram and in 1950 published an article in Journal of Political Economy, which is allegedly the first published version of a full AD–AS model in Y-P space. In 1951, Jacob Marschak published lecture notes providing the first full textbook treatment of the AD–AS model, presenting the same model as Brownlee's 1948 version, though not citing neither Brownlee nor anyone else.[1]

Growing popularity in 1970s

editIn the course of time, the model spread to several textbooks, becoming a standard modelling tool in principles and intermediate economics textbooks.[1] In particular, after inflation became important in the late 1960s and 1970s, there was a need to complement the IS–LM model, which had been a dominant model for teaching purposes until that time, but assumed a constant price level, with a model that incorporated aggregate supply and consequently could provide an explanation of changes in the price level. Thus, the "IS–LM–AS model", graphically depicted as an aggregate supply curve together with a curve combining the IS and LM curves and called an aggregate demand curve, became a standard teaching model only after the inflationary supply shocks of the 1970s.[1][2] In particular, two intermediate textbooks appearing in 1978 and later to be widely used, one by Rudi Dornbusch and Stanley Fischer, and one by Robert J. Gordon, together with William Hoban Branson's texbook from its second edition in 1979, all presented an AD–AS model.[1]

Rise of the dynamic AD–AS version

editFrom around the turn of the century, the traditional AD–AS diagram, as well as the traditional version of the IS–LM diagram, upon which the derivation of the AD curve rests, has been criticized for being obsolete. One reason is that the traditional IS–LM diagram and, consequently, AD curve rested upon the assumption of the central bank targeting money supply as its central policy variable. In contrast, central banks since around 1990 have largely abandoned controlling money supply, instead attempting to target inflation, using the policy interest rate as their main policy instrument, possibly via a Taylor rule-like strategy. Another reason is that for real-world policy purposes, it is generally not interesting to analyze the interaction between output and the price level per se, which is what the traditional AD–AS diagram illustrates, but rather between output and the change in the price level, i.e. inflation.[2][3][4]

Because of that, the original AD–AS model has increasingly been supplanted in textbooks by a dynamic version which directly analyzes equilibria in output and inflation levels, showing these variables along the axes of the diagram.[3][4][5] In some textbooks, the dynamic AD–AS version is referred to as the "three-equation New Keynesian model",[6] the three equations being an IS relation, often augmented with a term that allows for expectations influencing demand, a monetary policy (interest) rule and a short-run Phillips curve.[7] Olivier Blanchard in his widely-used[8] intermediate-level textbook uses the term IS–LM–PC model (PC standing for Phillips curve) for the same basic construction.[9]: 195–201

A stepping stone towards DSGE models

editThe dynamic AD–AS model can be viewed as a simplified version of the more advanced and complex dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models which are state-of-the-art models used by central banks and other organizations to analyze economic fluctuations. Unlike DSGE models, the dynamic AD–AS model does not provide a microeconomic foundation in the form of optimizing firms and households, but the macroeconomic relationships ultimately posited by the optimizing models are similar to those emerging from the modern-version AD–AS model.[5]: 427–428

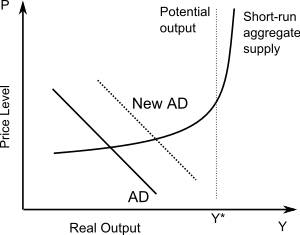

Static AD–AS model

editThe traditional or static AD/AS model illustrates the relationship between output and the price level of the economy under the assumptions of the model, containing both a short-run and a long-run aggregate supply curve (abbreviated SRAS and LRAS, respectively). In the short run wages and other resource prices are sticky and slow to adjust to new price levels. This gives way to an upward sloping or, in the extreme case of completely fixed prices, horizontal SRAS. In the long-run, resource prices adjust to the price level bringing the economy back to its structural output level along a vertical LRAS.[10] Movements of the two curves can be used to predict the effects that various exogenous events will have on two variables: real GDP and the price level.

Aggregate demand curve

editThe AD (aggregate demand) curve in the static AD–AS model is downward sloping, reflecting a negative correlation between output and the price level on the demand side. It shows the combinations of the price level and level of the output at which the goods and assets markets are simultaneously in equilibrium.

The equation for the AD curve in general terms can be written as:

- ,

where Y is real GDP, M is the nominal money supply, P is the price level, G is real government spending, T is real taxes levied, and Z1 any other variables that affect aggregate demand.[11]

Aggregate supply curve

editThe aggregate supply curve in the static AD–AS model illustrates the relationship between the supply of goods and services on the one hand and the price level on the other hand.[5]: 266 Under the premise that the price level is flexible in the long run, but sticky or even completely fixed under shorter time horizons, it is usual to distinguish between a long-run and a short-run aggregate supply curve. Whereas the long-run aggregate supply curve (LRAS) is vertical, the short-run aggregate supply curve will have a positive slope[5]: 377 or, in the extreme case of a completely constant price level, be horizontal.[5]: 268

The equation for the aggregate supply curve in general terms may be written as

- ,

where W is the nominal wage rate (exogenous due to stickiness in the short run), Pe is the anticipated (expected) price level, and Z2 is a vector of exogenous variables that can affect the position of the labor demand curve.

A horizontal aggregate supply curve (sometimes called a "Keynesian" aggregate supply curve) implies that the firm will supply whatever amount of goods is demanded at a particular price level. One possible justification for this is that when there is unemployment, firms can readily obtain as much labour as they want at that current wage, and production can increase without any additional costs (e.g. machines are idle which can simply be turned on). Firms' average costs of production therefore are assumed not to change as their output level changes.

The long-run aggregate supply curve refers not to a time frame in which the capital stock is free to be set optimally (as would be the terminology in the micro-economic theory of the firm), but rather to a time frame in which wages are free to adjust in order to equilibrate the labor market and in which price anticipations are accurate. A vertical long-run aggregate supply curve (sometimes called a "classical" aggregate supply curve) illustrates a situation where the level of output does not depend on the price level, but is exclusively determined by the supply of production factors like the capital and the labour force, employment being at its structural ("natural") level.[5]: 267

Dynamic AD–AS model

editThe modern or dynamic AD/AS model illustrates the connection between output and inflation, combining an IS relation (i.e., a relation describing aggregate demand as a function of various demand components, some of which are negatively related to the interest rate), a monetary policy rule determining the policy interest rate (which together form the AD curve) and a Phillips curve relationship from which the aggregate supply curve is derived.[3]: 263 [4]: 593–600

Aggregate demand curve

editThe AD curve slopes downward, illustrating a negative correlation between output and inflation. When the central bank observes increased inflation, it will raise its policy interest rate sufficiently to increase the real interest rate of the economy, dampening aggregate demand and consequently the overall activity level of the economy.[3]: 263 [5]: 411

Aggregate supply curve

editThe dynamic AS curve slopes upward, reflecting the mechanisms of the Phillips curve: Other things equal, higher levels of activity reflect higher increases in wages and other marginal costs of production, causing higher inflation through the firms' price-setting mechanisms[3]: 263 [5]: 409 as they induce firms to raise their prices at a higher rate.[4]: 594 There will be a vertical long-run aggregate supply curve at the level of structural (natural) output.[4]: 595

Shifts of aggregate demand and aggregate supply

editThe following summarizes the exogenous events that could shift the aggregate supply or aggregate demand curve to the right. Exogenous events happening in the opposite direction would shift the relevant curve in the opposite direction.

Shifts of aggregate demand

editThe dynamic aggregate demand curve shifts when either fiscal policy or monetary policy is changed or any other kinds of shocks to aggregate demand occur.[5]: 411 Changes in the level of potential Y also shifts the AD curve, so that this type of shocks has an effect on both the supply and the demand side of the model.[5]: 412

Rightward aggregate demand shifts can be caused by any shock to one of the autonomous components of aggregate demand, e.g.:

- An exogenous increase in consumer spending

- An exogenous increase in investment spending on physical capital

- An exogenous increase in intended inventory investment

- An exogenous increase in government spending on goods and services

- An exogenous increase in transfer payments from the government to the people

- An exogenous decrease in taxes levied

- An exogenous increase in purchases of the country's exports by people in other countries

- An exogenous decrease in imports from other countries

Shifts of aggregate supply

editThe dynamic aggregate supply curve is drawn for a given value of inflation expectations and level of potential output. Changes in either of these variables as well as a number of possible supply shocks will shift the dynamic aggregate supply curve.[5]: 409 [12]

The long-run aggregate supply curve is affected by events that affect the potential output of the economy. These include the following shocks which would shift the long-run aggregate supply curve to the right:

- An increase in population

- An increase in the physical capital stock

- Technological progress

Applications

editFunctional finance theory

editAD-AS analysis are applied to Functional Finance Theory and/or MMT to study a relationship between inflation rate and economic growth rate. When a country's economy grows, the country needs deficit spending to maintain full employment without inflation. Inflation starts to occur when the interest rate of its government bond becomes larger than the growth rate, provided that the country maintains full employment. Also, when the country recovers from recession, it needs to increase government expenditure to achieve full employment. [13]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Dutt, Amitava Krishna (1 June 2002). "Aggregate Demand-Aggregate Supply Analysis: A History". History of Political Economy. 34 (2): 321–364. doi:10.1215/00182702-34-2-321.

- ^ a b Romer, David (1 May 2000). "Keynesian Macroeconomics without the LM Curve". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 14 (2): 149–170. doi:10.1257/jep.14.2.149. ISSN 0895-3309. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Romer, David (2019). Advanced macroeconomics (Fifth ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 262–264. ISBN 978-1-260-18521-8.

- ^ a b c d e Sørensen, Peter Birch; Whitta-Jacobsen, Hans Jørgen (2022). Introducing advanced macroeconomics: growth and business cycles (Third ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-19-885049-6.

...we apply and extend the modern AS-AD framework where the nominal variable is the rate of inflation rather than the price level, and where monetary policy is specified as a Taylor rule for the nominal interest rate. This set-up is gradually superseding the traditional IS-LM and AS-AD analysis and makes it easier to relate the model to real-world policy discussions.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mankiw, Nicholas Gregory (2022). Macroeconomics (Eleventh, international ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers, Macmillan Learning. ISBN 978-1-319-26390-4.

- ^ Davis, Leila E.; Gómez-Ramírez, Leopoldo (2 October 2022). "Teaching post-intermediate macroeconomics with a dynamic 3-equation model". The Journal of Economic Education. 53 (4): 348–367. doi:10.1080/00220485.2022.2111385. ISSN 0022-0485. S2CID 252249958. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ de Araujo, Pedro; O’Sullivan, Roisin; Simpson, Nicole B. (January 2013). "What Should be Taught in Intermediate Macroeconomics?". The Journal of Economic Education. 44 (1): 74–90. doi:10.1080/00220485.2013.740399. ISSN 0022-0485. S2CID 17167083. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Courtoy, François; De Vroey, Michel; Turati, Riccardo. "What do we teach in Macroeconomics? Evidence of a Theoretical Divide" (PDF). sites.uclouvain.be. UCLouvain. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ Blanchard, Olivier (2021). Macroeconomics (Eighth, global ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-134-89789-9.

- ^ Reed, Jacob (2016). "AP Macroeconomics Review: AS-AD Model". APEconReview.com. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ Salter, Alexander W. "Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply: Keep It Simple, Stupid! | AIER". www.aier.org. Retrieved 2024-03-24.

- ^ "The Great Recession: A Macroeconomic Earthquake | Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis". www.minneapolisfed.org. Retrieved 2024-03-24.

- ^ Tanaka, Y. (June 2023). "AD-AS Analysis from the Perspective of Functional Finance Theory and MMT". Folia Oeconomica Stetinensia. 23.

Further reading

edit- Blanchard, Olivier (2021). Macroeconomics (Eighth, global ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-134-89789-9.

- Dutt, Amitava K.; Skott, Peter (1996). "Keynesian Theory and the Aggregate-Supply/Aggregate-Demand Framework: A Defense". Eastern Economic Journal. 22 (3): 313–331.

- Dutt, Amitava K.; Skott, Peter (2006). "Keynesian Theory and the AD-AS Framework: A Reconsideration". In Chiarella, Carl; Franke, Reiner; Flaschel, Peter; Semmler, Willi (eds.). Quantitative and Empirical Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamic Macromodels. Contributions to Economic Analysis. Vol. 277. Emerald Group. pp. 149–172. doi:10.1016/S0573-8555(05)77006-1. ISBN 978-0-444-52122-4. S2CID 16009286.

- Mankiw, Nicholas Gregory (2022). Macroeconomics (Eleventh, international ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers, Macmillan Learning. ISBN 978-1-319-26390-4.

- Palley, Thomas I. (1997). "Keynesian Theory and AS/AD Analysis". Eastern Economic Journal. 23 (4): 459–468. JSTOR 40325806.

- Romer, David (2019). Advanced macroeconomics (Fifth ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-1-260-18521-8.

- Sørensen, Peter Birch; Whitta-Jacobsen, Hans Jørgen (2022). Introducing advanced macroeconomics: growth and business cycles (Third ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-885049-6.

External links

edit- Sparknotes: Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand brief explanation of the AD–AS model

- "Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply" in CyberEconomics by Robert Schenk explains the AD–AS model and explains its relation to the IS/LM model

- "ThinkEconomics: Macroeconomic Phenomena in the AD/AS Model" includes an interactive graph demonstrating inflationary changes in a graph based on the AD–AS model

- "ThinkEconomics: The Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply Model" includes an interactive AD-AS graph that tests one's knowledge of how the AD and AS curves shift under different conditions