This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Oromo (/ˈɒrəmoʊ/[5] OR-əm-ow or /ɔːˈroʊmoʊ/[6][7] aw-ROW-mow; Oromo: Afaan Oromoo), historically also called Galla,[8] which is regarded by the Oromo as pejorative,[9] is an Afroasiatic language that belongs to the Cushitic branch. It is native to the Ethiopian state of Oromia and northern Kenya and is spoken predominantly by the Oromo people and neighboring ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa. It is used as a lingua franca particularly in the Oromia Region and northeastern Kenya.[10][11][12]

| Oromo | |

|---|---|

| Afaan Oromoo | |

"Afaan Oromoo" in the Sheek Bakrii Saphaloo script invented by Bakri Sapalo[1] | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈɒrəmoʊ/ or /ɔːˈroʊmoʊ/ |

| Native to | Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia[2] |

| Region | Oromia |

| Ethnicity | Oromo |

Native speakers | 45.5 million (all countries) (2022–2024)[3] |

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | om |

| ISO 639-2 | orm |

| ISO 639-3 | orm – inclusive codeIndividual codes: gax – Borana–Arsi–Guji Oromohae – Eastern Oromoorc – Ormagaz – West Central Oromossn – Waata |

| Glottolog | nucl1736 |

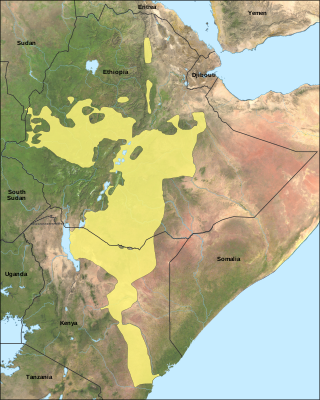

Areas in East Africa where Oromo is spoken | |

With more than 41.7 million speakers[13] making up 33.8% of the total Ethiopian population,[14] Oromo has the largest number of native speakers in Ethiopia, and ranks as the second most widely spoken language in Ethiopia by total number of speakers (including second-language speakers) following Amharic.[15] Forms of Oromo are spoken as a first language by an additional half-million people in parts of northern and eastern Kenya.[16] It is also spoken by smaller numbers of emigrants in other African countries such as South Africa, Libya, Egypt and Sudan. Oromo is the most widely spoken Cushitic language and among the five languages of Africa with the largest mother-tongue populations.[17]

Oromo serves as one of the official working languages of Ethiopia[4] and is also the working language of several of the states within the Ethiopian federal system including Oromia,[14] Harari and Dire Dawa regional states and of the Oromia Zone in the Amhara Region. It is a language of primary education in Oromia, Harari, Dire Dawa, Benishangul-Gumuz and Addis Ababa and of the Oromia Zone in the Amhara Region. It is used as an internet language for federal websites along with Tigrinya.[18][19] Under Haile Selassie's regime, Oromo was banned in education, in conversation, and in administrative matters.[20][21][22]

Varieties

editEthnologue (2015) assigns five ISO codes to Oromo:

- Boranaa–Arsii–Gujii Oromo (Southern Oromo, including Gabra and Sakuye dialects), ISO code [gax]

- Eastern Oromo (Harar), ISO code [hae]

- Orma (Munyo, Orma, Waata/Sanye), ISO code [orc]

- West–Central Oromo (Western Oromo and Central Oromo, including Mecha/Wollega, Raya, Wello (Kemise), Tulema/Shewa), ISO code [gaz]

- Waata, ISO code [ssn]

Blench (2006)[23] divides Oromo into four languages:

- Western Oromo (Maca)

- Shewa (Tuulama, Arsi)

- Eastern Oromo (Harar)

- Southern Oromo (Ajuran, Borana, Gabra, Munyo, Orma, Sakuye, Waata)

Some of the varieties of Oromo have been examined and classified.[24]

Speakers

editAbout 85 percent of Oromo speakers live in Ethiopia, mainly in the Oromia Region. In addition, in Somalia there are also some speakers of the language.[25] In Kenya, the Ethnologue also lists 722,000 speakers of Borana and Orma, two languages closely related to Ethiopian Oromo.[26] Within Ethiopia, Oromo is the language with the largest number of native speakers.

Within Africa, Oromo is the language with the fourth most speakers, after Arabic (if one counts the mutually unintelligible spoken forms of Arabic as a single language and assumes the same for the varieties of Oromo), Swahili, and Hausa.

Besides first language speakers, a number of members of other ethnicities who are in contact with the Oromo speak it as a second language. See, for example, the Omotic-speaking Bambassi and the Nilo-Saharan-speaking Kwama in northwestern Oromia.[27]

Language policy

editThe Oromo people use a highly developed oral tradition. In the 19th century, scholars began writing in the Oromo language using Latin script. In 1842, Johann Ludwig Krapf began translations of the Gospels of John and Matthew into Oromo, as well as a first grammar and vocabulary. The first Oromo dictionary and grammar was produced by German scholar Karl Tutschek in 1844.[28] The first printing of a transliteration of Oromo language was in 1846 in a German newspaper in an article on the Oromo in Germany.[29]

After Abyssinia annexed Oromo's territory, the language's development into a full-fledged writing instrument was interrupted. The few works that had been published, most notably Onesimos Nesib's and Aster Ganno's translations of the Bible from the late 19th century, were written in the Ge'ez alphabet. Following the 1974 Revolution, the government undertook a literacy campaign in several languages, including Oromo, and publishing and radio broadcasts began in the language. All Oromo materials printed in Ethiopia at that time, such as the newspaper Bariisaa, Urjii and many others, were written in the traditional Ethiopic script.[citation needed]

Plans to introduce Oromo language instruction in schools, however, were not realized until the government of Mengistu Haile Mariam was overthrown in 1991, except in regions controlled by the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF). With the creation of the regional state of Oromia under the new system of ethnic federalism in Ethiopia, it has been possible to introduce Oromo as the medium of instruction in elementary schools throughout the region, including areas where other ethnic groups live speaking their languages, and as a language of administration within the region. Since the OLF left the transitional Ethiopian government in the early 1990s, the Oromo Peoples' Democratic Organization (OPDO) continued developing Oromo in Ethiopia.[citation needed]

Radio broadcasts began in the Oromo language in Somalia in 1960 by Radio Mogadishu.[30] The programme featured music and propaganda. A song Bilisummaan Aannaani (Liberation is Milk) became a hit in Ethiopia. To combat Somali wide-reaching influence, the Ethiopian Government initiated an Oromo language program radio of their own.[31] Within Kenya there has been radio broadcasting in Oromo (in the Borana dialect) on the Voice of Kenya since at least the 1980s.[32] The Borana Bible in Kenya was printed in 1995 using the Latin alphabet, but not using the same spelling rules as in Ethiopian Qubee. The first comprehensive online Oromo dictionary was developed by the Jimma Times Oromiffa Group (JTOG) in cooperation with SelamSoft.[33] Voice of America also broadcasts in Oromo alongside its other horn of Africa programs. In May 2022, Google Translate added Afaan Oromo as translation. Oromo and Qubee are currently utilized by the Ethiopian government's state radios, TV stations and regional government newspaper.

Phonology and orthography

editWriting systems

editOromo is written with a Latin alphabet called Qubee which was formally adopted in 1991.[34] Various versions of the Latin-based orthography had been used previously, mostly by Oromos outside of Ethiopia and by the OLF by the late 1970s (Heine 1986).[35] With the adoption of Qubee, it is believed more texts were written in the Oromo language between 1991 and 1997 than in the previous 100 years. In Kenya, the Borana and Waata also use Roman letters but with different systems.

The Sapalo script was an indigenous Oromo script invented by Sheikh Bakri Sapalo (1895–1980; also known by his birth name, Abubaker Usman Odaa) in the late 1950s, and used underground afterwards. Despite structural and organizational influences from Ge'ez and the Arabic script, it is a graphically independent creation designed specifically for Oromo phonology. It is largely an Abugida in nature, but lacks the inherent vowel present in many such systems; in actual use, all consonant characters are obligatorily marked either with vowel signs (producing CV syllables) or with separate marks used to denote geminated consonants or pure/standalone consonants not followed by a vowel (e.g. in word-final environments or as part of consonant clusters).[36][37]

The Arabic script has also been used intermittently in areas with Muslim populations.

Consonant and vowel phonemes

editLike most other Ethiopian languages, whether Semitic, Cushitic, or Omotic, Oromo has a set of ejective consonants, that is, voiceless stops or affricates that are accompanied by glottalization and an explosive burst of air. Oromo has another glottalized phone that is more unusual, an implosive retroflex stop, "dh" in Oromo orthography, a sound that is like an English "d" produced with the tongue curled back slightly and with the air drawn in so that a glottal stop is heard before the following vowel begins. It is retroflex in most dialects, though it is not strongly implosive and may reduce to a flap between vowels.[38] One source describes it as voiceless [ᶑ̥].[39]

Oromo has the typical Eastern Cushitic set of five short and five long vowels, indicated in the orthography by doubling the five vowel letters. The difference in length is contrastive, for example, hara 'lake', haaraa 'new'. Gemination is also significant in Oromo. That is, consonant length can distinguish words from one another, for example, badaa 'bad', baddaa 'highland'.

In the Qubee alphabet, letters include the digraphs[40] ch, dh, ny, ph, sh. Gemination is not obligatorily marked for digraphs, though some writers indicate it by doubling the first element: qopphaa'uu 'be prepared'. In the charts below, the International Phonetic Alphabet symbol for a phoneme is shown in brackets where it differs from the Oromo letter. The phonemes /p v z/ appear in parentheses because they are only found in recently adopted words. There have been minor changes in the orthography since it was first adopted: ⟨x⟩ ([tʼ]) was originally rendered ⟨th⟩, and there has been some confusion among authors in the use of ⟨c⟩ and ⟨ch⟩ in representing the phonemes /tʃʼ/ and /tʃ/, with some early works using ⟨c⟩ for /tʃ/ and ⟨ch⟩ for /tʃʼ/ and even ⟨c⟩ for different phonemes depending on where it appears in a word. This article uses ⟨c⟩ consistently for /tʃʼ/ and ⟨ch⟩ for /tʃ/.

| Labial | Alveolar/ Retroflex |

Palato- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives and Affricates |

voiceless | (p) | t | tʃ ⟨ch⟩ | k | ʔ ⟨'⟩ |

| voiced | b | d | dʒ ⟨j⟩ | ɡ ⟨g⟩ | ||

| ejective | pʼ ⟨ph⟩ | tʼ ⟨x⟩ | tʃʼ ⟨c⟩ | kʼ ⟨q⟩ | ||

| implosive | ᶑ ⟨dh⟩ | |||||

| Fricatives | voiceless | f | s | ʃ ⟨sh⟩ | h | |

| voiced | (v) | (z) | ||||

| Nasals | m | n | ɲ ⟨ny⟩ | |||

| Approximants | w | l | j ⟨y⟩ | |||

| Rhotic | r | |||||

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | ɪ ⟨i⟩, iː ⟨ii⟩ | ʊ ⟨u⟩, uː ⟨uu⟩ | |

| Mid | ɛ ⟨e⟩, eː ⟨ee⟩ | ɔ ⟨o⟩, oː ⟨oo⟩ | |

| Open | ɐ ⟨a⟩ | ɑː ⟨aa⟩ |

Tone and stress

editOnly the penultimate or final syllable of a root can have a high tone, and if the penultimate is high, the final must also be high;[41] this implies that Oromo has a pitch-accent system (in which the tone need be specified only on one syllable, the others being predictable) rather than a tone system (in which each syllable must have its tone specified),[42] although the rules are complex (each morpheme can contribute its own tone pattern to the word), so that "one can call Oromo a pitch-accent system in terms of the basic lexical representation of pitch, and a tone system in terms of its surface realization."[43] The stressed syllable is perceived as the first syllable of a word with high pitch.[44]

Grammar

editNouns

editGender

editLike most other Afroasiatic languages, Oromo has two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine, and all nouns belong to either one or the other. Grammatical gender in Oromo enters into the grammar in the following ways:

- Verbs (except for the copula be) agree with their subjects in gender when the subject is third person singular (he or she).

- Third person singular personal pronouns (he, she, it, etc., in English) have the gender of the noun they refer to.

- Adjectives agree with the nouns they modify in gender.

- Some possessive adjectives ("my", "your") agree with the nouns they modify in some dialects.

Except in some southern dialects, there is nothing in the form of most nouns that indicates their gender. A small number of nouns pairs for people, however, end in -eessa (m.) and -eettii (f.), as do adjectives when they are used as nouns: obboleessa 'brother', obboleettii 'sister', dureessa 'the rich one (m.)', hiyyeettii 'the poor one (f.)'. Grammatical gender normally agrees with natural gender for people and animals; thus nouns such as Abbaa 'father', Ilma 'son', and sangaa 'ox' are masculine, while nouns such as haadha 'mother' and intala 'girl, daughter' are feminine. However, most names for animals do not specify biological gender.

Names of astronomical bodies are feminine: aduu 'sun', urjii 'star'. The gender of other inanimate nouns varies somewhat among dialects.

Number

editOromo displays singular and plural number, but nouns that refer to multiple entities are not obligatorily plural: nama 'man' namoota 'people', nama shan 'five men' namoota shan 'five people'. Another way of looking at this is to treat the "singular" form as unspecified for number.

When it is important to make the plurality of a referent clear, the plural form of a noun is used. Noun plurals are formed through the addition of suffixes. The most common plural suffix is -oota; a final vowel is dropped before the suffix, and in the western dialects, the suffix becomes -ota following a syllable with a long vowel: mana 'house', manoota 'houses', hiriyaa 'friend', hiriyoota 'friends', barsiisaa 'teacher', barsiiso(o)ta 'teachers'. Among the other common plural suffixes are -(w)wan, -een, and -(a)an; the latter two may cause a preceding consonant to be doubled: waggaa 'year', waggaawwan 'years', laga 'river', laggeen 'rivers', ilma 'son', ilmaan 'sons'.

Definiteness

editOromo has no indefinite articles (corresponding to English a, some), but (except in the southern dialects) it indicates definiteness (English the) with suffixes on the noun: -(t)icha for masculine nouns (the ch is geminated though this is not normally indicated in writing) and -(t)ittii for feminine nouns. Vowel endings of nouns are dropped before these suffixes: karaa 'road', karicha 'the road', nama 'man', namicha/namticha 'the man', haroo 'lake', harittii 'the lake'. For animate nouns that can take either gender, the definite suffix may indicate the intended gender: qaalluu 'priest', qaallicha 'the priest (m.)', qallittii 'the priest (f.)'. The definite suffixes appear to be used less often than the in English, and they seem not to co-occur with the plural suffixes.

Case

editOromo nouns appear in seven grammatical cases, each indicated by a suffix, the lengthening of the noun's final vowel, or both. For some of the cases, there is a range of forms possible, some covering more than one case, and the differences in meaning among these alternatives may be quite subtle.

- Absolutive

- The absolutive case is the citation form or base form that is used when the noun is the object of a verb, the object of a preposition or postposition, or a nominal predicative.

- mana 'house', mana binne 'we bought a house'

- hamma 'until', dhuma 'end', hamma dhumaatti 'until (the) end'

- mana keessa, 'inside (a/the) house'

- inni 'he', barsiisaa 'teacher'

- inni barsiisaa (dha) 'he is a teacher'

- Nominative

- The nominative is used for nouns that are the subjects of clauses.

- Ibsaa (a name), Ibsaan 'Ibsaa (nom.)', konkolaataa '(a) car', qaba 'he has':

- Ibsaan konkolaataa qaba 'Ibsaa has a car'.

- Most nouns ending in short vowels with a preceding single consonant drop the final vowel and add -ni to form the nominative. Following certain consonants, assimilation changes either the n or that consonant (the details depend on the dialect).

- nama 'man', namni 'man (nom.)'

- namoota 'men'; namootni, namoonni 'men (nom.)' (t + n may assimilate to nn)

- If a final short vowel is preceded by two consonants or a geminated consonant, -i is suffixed.

- ibsa 'statement', ibsi 'statement (nom.)'

- namicha 'the man', namichi 'the man (nom.)' (the ch in the definite suffix -icha is actually geminated, though not normally written as such)

- If the noun ends in a long vowel, -n is suffixed to this. This pattern applies to infinitives, which end in -uu.

- maqaa 'name', maqaan 'name (nom.)'

- nyachuu 'to eat, eating', nyachuun 'to eat, eating (nom.)'

- If the noun ends in n, the nominative is identical to the base form.

- afaan 'mouth, language (base form or nom.)'

- Some feminine nouns ending in a short vowel add -ti. Again assimilation occurs in some cases.

- haadha 'mother', haati (dh + t assimilates to t)

- lafa 'earth', lafti

- Genitive

- The genitive is used for possession or "belonging"; it corresponds roughly to English of or -'s. The genitive is usually formed by lengthening a final short vowel, by adding -ii to a final consonant, and by leaving a final long vowel unchanged. The possessor noun follows the possessed noun in a genitive phrase. Many such phrases with specific technical meanings have been added to the Oromo lexicon in recent years.

- obboleetti 'sister', namicha 'the man', obboleetti namichaa 'the man's sister'

- hojii 'job', Caaltuu, woman's name, hojii Caaltuu, 'Caaltuu's job'

- barumsa 'field of study', afaan 'mouth, language', barumsa afaanii 'linguistics'

- In place of the genitive it is also possible to use the relative marker kan (m.) / tan (f.) preceding the possessor.

- obboleetti kan namicha 'the man's sister'

- Dative

- The dative is used for nouns that represent the recipient (to) or the benefactor (for) of an event. The dative form of a verb infinitive (which acts like a noun in Oromo) indicates purpose. The dative takes one of the following forms:

- Lengthening of a final short vowel (ambiguously also signifying the genitive)

- namicha 'the man', namichaa 'to the man, of the man'

- -f following a long vowel or a lengthened short vowel; -iif following a consonant

- intala 'girl, daughter', intalaaf 'to a girl, daughter'

- saree 'dog', sareef 'to a dog'

- baruu 'to learn', baruuf 'in order to learn'

- bishaan 'water', bishaaniif 'for water'

- -dhaa or -dhaaf following a long vowel

- saree 'dog'; sareedhaa, sareedhaaf 'to a dog'

- -tti (with no change to a preceding vowel), especially with verbs of speaking

- Caaltuu woman's name, himi 'tell, say (imperative)', Caaltuutti himi 'tell Caaltuu'

- Instrumental

- The instrumental is used for nouns that represent the instrument ("with"), the means ("by"), the agent ("by"), the reason, or the time of an event. The formation of the instrumental parallels that of the dative to some extent:

- -n following a long vowel or a lengthened short vowel; -iin following a consonant

- harka 'hand', harkaan 'by hand, with a hand'

- halkan 'night', halkaniin 'at night'

- -tiin following a long vowel or a lengthened short vowel

- Afaan Oromo 'Oromo (language)', Afaan Oromootiin 'in Oromo'

- -dhaan following a long vowel

- yeroo 'time', yeroodhaan 'on time'

- bawuu 'to come out, coming out', bawuudhaan 'by coming out'

- Locative

- The locative is used for nouns that represent general locations of events or states, roughly at. For more specific locations, Oromo uses prepositions or postpositions. Postpositions may also take the locative suffix. The locative also seems to overlap somewhat with the instrumental, sometimes having a temporal function. The locative is formed with the suffix -tti.

- Arsiitti 'in Arsii'

- harka 'hand', harkatti 'in hand'

- guyyaa 'day', guyyaatti 'per day'

- jala, jalatti 'under'

- Ablative

- The ablative is used to represent the source of an event; it corresponds closely to English from. The ablative, applied to postpositions and locative adverbs as well as nouns proper, is formed in the following ways:

- When the word ends in a short vowel, this vowel is lengthened (as for the genitive).

- biyya 'country', biyyaa 'from country'

- keessa 'inside, in', keessaa 'from inside'

- When the word ends in a long vowel, -dhaa is added (as for one alternative for the dative).

- Finfinneedhaa 'from Finfinne'

- gabaa 'market', gabaadhaa 'from market'

- When the word ends in a consonant, -ii is added (as for the genitive).

- Hararii 'from Harar'

- Following a noun in the genitive, -tii is added.

- mana 'house', buna 'coffee', mana bunaa 'cafe', mana bunaatii 'from cafe'

- An alternative to the ablative is the postposition irraa 'from' whose initial vowel may be dropped in the process:

- gabaa 'market', gabaa irraa, gabaarraa 'from market'

Pronouns

editPersonal pronouns

editIn most languages, there is a small number of basic distinctions of person, number, and often gender that play a role within the grammar of the language. Oromo and English are such languages. We see these distinctions within the basic set of independent personal pronouns, for example, English I, Oromo ani; English they, Oromo 'isaani' and the set of possessive adjectives and pronouns, for example, English my, Oromo koo; English mine, Oromo kan koo. In Oromo, the same distinctions are also reflected in subject–verb agreement: Oromo verbs (with a few exceptions) agree with their subjects; that is, the person, number, and (singular third person) gender of the subject of the verb are marked by suffixes on the verb. Because these suffixes vary greatly with the particular verb tense/aspect/mood, they are normally not considered to be pronouns and are discussed elsewhere in this article under verb conjugation.

In all of these areas of the grammar—independent pronouns, possessive adjectives, possessive pronouns, and subject–verb agreement—Oromo distinguishes seven combinations of person, number, and gender. For first and second persons, there is a two-way distinction between singular ('I', 'you sg.') and plural ('we', 'you pl.'), whereas for third person, there is a two-way distinction in the singular ('he', 'she') and a single form for the plural ('they'). Because Oromo has only two genders, there is no pronoun corresponding to English it; the masculine or feminine pronoun is used according to the gender of the noun referred to.

Oromo is a subject pro-drop language. That is, neutral sentences in which the subject is not emphasized do not require independent subject pronouns: kaleessa dhufne 'we came yesterday'. The Oromo word that translates 'we' does not appear in this sentence, though the person and number are marked on the verb dhufne ('we came') by the suffix -ne. When the subject in such sentences needs to be given prominence for some reason, an independent pronoun can be used: 'nuti kaleessa dhufne' 'we came yesterday'.

The table below gives forms of the personal pronouns in the different cases, as well as the possessive adjectives. For the first person plural and third person singular feminine categories, there is considerable variation across dialects; only some of the possibilities are shown.

The possessive adjectives, treated as separate words here, are sometimes written as noun suffixes. In most dialects there is a distinction between masculine and feminine possessive adjectives for first and second person (the form agreeing with the gender of the modified noun). However, in the western dialects, the masculine forms (those beginning with k-) are used in all cases. Possessive adjectives may take the case endings for the nouns they modify: ganda kootti 'to my village' (-tti: locative case).

| English | Base | Subject | Dative | Instrumental | Locative | Ablative | Possessive adjectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | ana, na | ani, an | naa, naaf, natti | naan | natti | narraa | koo, kiyya [too, tiyya (f.)] |

| you (sg.) | si | ati | sii, siif, sitti | siin | sitti | sirraa | kee [tee (f.)] |

| he | isa | inni | isaa, isaa(tii)f, isatti | isaatiin | isatti | isarraa | (i)saa |

| she | isii, ishii, isee, ishee | isiin, etc. | ishii, ishiif, ishiitti, etc. | ishiin, etc. | ishiitti, etc. | ishiirraa, etc. | (i)sii, (i)shii |

| we | nu | nuti, nu'i, nuy, nu | nuu, nuuf, nutti | nuun | nutti | nurraa | keenna, keenya [teenna, teenya (f.)] |

| you (pl.) | isin | isini | isinii, isiniif, isinitti | isiniin | isinitti | isinirraa | keessan(i) [teessan(i) (f.)] |

| they | isaan | isaani | isaanii, isaaniif, isaanitti | isaaniitiin | isaanitti | isaanirraa | (i)saani |

As in languages such as French, Russian, and Turkish, the Oromo second person plural is also used as a polite singular form, for reference to people that the speaker wishes to show respect towards. This usage is an example of the so-called T-V distinction that is made in many languages. In addition, the third person plural may be used for polite reference to a single third person (either 'he' or 'she').

For possessive pronouns ('mine', 'yours', etc.), Oromo adds the possessive adjectives to kan 'of': kan koo 'mine', kan kee 'yours', etc.

Reflexive and reciprocal pronouns

editOromo has two ways of expressing reflexive pronouns ('myself', 'yourself', etc.). One is to use the noun meaning 'self': of(i) or if(i). This noun is inflected for case but, unless it is being emphasized, not for person, number, or gender: isheen of laalti 'she looks at herself' (base form of of), isheen ofiif makiinaa bitte 'she bought herself a car' (dative of of).

The other possibility is to use the noun meaning 'head', mataa, with possessive suffixes: mataa koo 'myself', mataa kee 'yourself (s.)', etc.

Oromo has a reciprocal pronoun wal (English 'each other') that is used like of/if. That is, it is inflected for case but not person, number, or gender: wal jaalatu 'they like each other' (base form of wal), kennaa walii bitan 'they bought each other gifts' (dative of wal).

Demonstrative pronouns

editLike English, Oromo makes a two-way distinction between proximal ('this, these') and distal ('that, those') demonstrative pronouns and adjectives. Some dialects distinguish masculine and feminine for the proximal pronouns; in the western dialects the masculine forms (beginning with k-) are used for both genders. Unlike in English, singular and plural demonstratives are not distinguished, but, as for nouns and personal pronouns in the language, case is distinguished. Only the base and nominative forms are shown in the table below; the other cases are formed from the base form as for nouns, for example, sanatti 'at/on/in that' (locative case).

| Case | Proximal ('this, these') |

Distal ('that, those') |

|---|---|---|

| Base | kana [tana (f.)] |

san |

| Nominative | kuni [tuni (f.)] |

suni |

Verbs

editAn Oromo verb consists minimally of a stem, representing the lexical meaning of the verb, and a suffix, representing tense or aspect and subject agreement. For example, in dhufne 'we came', dhuf- is the stem ('come') and -ne indicates that the tense is past and that the subject of the verb is first person plural.

As in many other Afroasiatic languages, Oromo makes a basic two-way distinction in its verb system between the two tensed forms, past (or "perfect") and present (or "imperfect" or "non-past"). Each of these has its own set of tense/agreement suffixes. There is a third conjugation based on the present which has three functions: it is used in place of the present in subordinate clauses, for the jussive ('let me/us/him, etc. V', together with the particle haa), and for the negative of the present (together with the particle hin). For example, deemne 'we went', deemna 'we go', akka deemnu 'that we go', haa deemnu 'let's go', hin deemnu 'we don't go'. There is also a separate imperative form: deemi 'go (sg.)!'.

Conjugation

editThe table below shows the conjugation in the affirmative and negative of the verb beek- 'know'. The first person singular present and past affirmative forms require the suffix -n to appear on the word preceding the verb or the word nan before the verb. The negative particle hin, shown as a separate word in the table, is sometimes written as a prefix on the verb.

| Past | Present | Jussive, Imperative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main clause | Subordinate clause | |||||||

| Affirmative | Negative | Affirmative | Negative | Affirmative | Negative | Affirmative | Negative | |

| I | -n beeke | hin beekne | -n beeka | hin beeku | -n beeku | hin beekne | haa beeku | hin beekin |

| you (sg.) | beekte | beekta | hin beektu | beektu | beeki | hin beek(i)in | ||

| he | beeke | beeka | hin beeku | beeku | haa beeku | hin beekin | ||

| she | beekte | beekti | hin beektu | beektu | haa beektu | |||

| we | beekne | beekna | hin beeknu | beeknu | haa beeknu | |||

| you (pl.) | beektani | beektu, beektan(i) | hin beektan | beektani | beekaa | hin beek(i)inaa | ||

| they | beekani | beeku, beekan(i) | hin beekan | beekani | haa beekanu | hin beekin | ||

For verbs with stems ending in certain consonants and suffixes beginning with consonants (that is, t or n), there are predictable changes to one or the other of the consonants. The dialects vary a lot in the details, but the following changes are common.

| b- + -t → bd | qabda 'you (sg.) have' |

| g- + -t → gd | dhugda 'you (sg.) drink' |

| r- + -n → rr | barra 'we learn' |

| l- + -n → ll | galla 'we enter' |

| q- + -t → qx | dhaqxa 'you (sg.) go' |

| s- + -t → ft | baas- 'take out', baafta 'you (sg.) take out' |

| s- + -n → fn | baas- 'take out', baafna 'we take out' |

| t-/d-/dh-/x- + -n → nn | biti 'buy', binna 'we buy'; nyaadhaa 'eat', nyaanna 'we eat' |

| d- + -t → dd | fid- 'bring', fidda 'you (sg.) bring' |

| dh- + -t → tt | taphadh- 'play', taphatta 'you (sg.) play' |

| x- + -t → xx | fix- 'finish', fixxa 'you (sg.) finish' |

Verbs whose stems end in two consonants and whose suffix begins with a consonant must insert a vowel to break up the consonants since the language does not permit sequences of three consonants. There are two ways this can happen: either the vowel i is inserted between the stem and the suffix, or the final stem consonants are switched (an example of metathesis) and the vowel a is inserted between them. For example, arg- 'see', arga 'he sees', argina or agarra (from agar-na) 'we see'; kolf- 'laugh', kolfe 'he laughed', kolfite or kofalte 'you (sg.) laughed'.

Verbs whose stems end in the consonant ' (which may appear as h, w, or y in some words, depending on the dialect) belong to three different conjugation classes; the class is not predictable from the verb stem. It is the forms that precede suffixes beginning with consonants (t and n) that differ from the usual pattern. The third person masculine singular, second person singular, and first person plural present forms are shown for an example verb in each class.

- du'- 'die': du'a 'he dies', duuta 'you (sg.) die', duuna 'we die'

- beela'-, 'be hungry': beela'a 'he is hungry', beelofta 'you (sg.) are hungry', beelofna 'we are hungry'

- dhaga'- 'hear': dhaga'a 'he hears', dhageessa 'you (sg.) hear', dhageenya 'we hear' (the suffix consonants change)

The common verbs fedh- 'want' and godh- 'do' deviate from the basic conjugation pattern in that long vowels replace the geminated consonants that would result when suffixes beginning with t or n are added: fedha 'he wants', feeta 'you (sg.) want', feena 'we want', feetu 'you (pl.) want', hin feene 'didn't want', etc.

The verb dhuf- 'come' has the irregular imperatives koottu, koottaa. The verb deem- 'go' has, alongside regular imperative forms, the irregular imperatives deemi, deemaa.

Derivation

editAn Oromo verb root can be the basis for three derived voices, passive, causative, and autobenefactive, each formed with addition of a suffix to the root, yielding the stem that the inflectional suffixes are added to.

- Passive voice

- The Oromo passive corresponds closely to the English passive in function. It is formed by adding -am to the verb root. The resulting stem is conjugated regularly. Examples: beek- 'know', beekam- 'be known', beekamani 'they were known'; jedh- 'say', jedham- 'be said', jedhama 'it is said'

- Causative voice

- The Oromo causative of a verb V corresponds to English expressions such as 'cause V', 'make V', 'let V'. With intransitive verbs, it has a transitivizing function. It is formed by adding -s, -sis, or -siis to the verb root, except that roots ending in -l add -ch. Verbs whose roots end in ' drop this consonant and may lengthen the preceding vowel before adding -s. Examples: beek- 'know', beeksis- 'cause to know, inform', beeksifne 'we informed'; ka'- 'go up, get up', kaas- 'pick up', kaasi 'pick up (sing.)!'; gal- 'enter', galch- 'put in', galchiti 'she puts in'; bar- 'learn', barsiis- 'teach', nan barsiisa 'I teach'.

- Autobenefactive voice

- The Oromo autobenefactive (or "middle" or "reflexive-middle") voice of a verb V corresponds roughly to English expressions such as 'V for oneself' or 'V on one's own', though the precise meaning may be somewhat unpredictable for many verbs. It is formed by adding -adh to the verb root. The conjugation of a middle verb is irregular in the third person singular masculine of the present and past (-dh in the stem changes to -t) and in the singular imperative (the suffix is -u rather than -i). Examples: bit- 'buy', bitadh- 'buy for oneself', bitate 'he bought (something) for himself', bitadhu 'buy for yourself (sing.)!'; qab- 'have', qabadh- 'seize, hold (for oneself)', qabanna 'we hold'. Some autobenefactives are derived from nouns rather than verbs, for example, hojjadh- 'work' from the noun hojii 'work'.

The voice suffixes can be combined in various ways. Two causative suffixes are possible: ka'- 'go up', kaas- 'pick up', kaasis- 'cause to pick up'. The causative may be followed by the passive or the autobenefactive; in this case the s of the causative is replaced by f: deebi'- 'return (intransitive)', deebis- 'return (transitive), answer', deebifam- 'be returned, be answered', deebifadh- 'get back for oneself'.

Another derived verbal aspect is the frequentative or "intensive," formed by copying the first consonant and vowel of the verb root and geminating the second occurrence of the initial consonant. The resulting stem indicates the repetition or intensive performance of the action of the verb. Examples: bul- 'spend the night', bubbul- 'spend several nights', cab- 'break', caccab- 'break to pieces, break completely'; dhiib- 'push, apply pressure', dhiddhiib- 'massage'.

The infinitive is formed from a verb stem with the addition of the suffix -uu. Verbs whose stems end in -dh (in particular all autobenefactive verbs) change this to ch before the suffix. Examples: dhug- 'drink', dhuguu 'to drink'; ga'- 'reach', ga'uu 'to reach'; jedh- 'say', jechu 'to say'. The verb fedh- is exceptional; its infinitive is fedhuu rather than the expected fechuu. The infinitive behaves like a noun; that is, it can take any of the case suffixes. Examples: ga'uu 'to reach', ga'uuf 'in order to reach' (dative case); dhug- 'drink', dhugam- 'be drunk', dhugamuu to be drunk', dhugamuudhaan 'by being drunk' (instrumental case).

References

edit- ^ https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2024/24109-sheek-bakrii-saphaloo.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2024). "Oromo". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Twenty Seventh ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Oromo at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

Borana–Arsi–Guji Oromo at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

Eastern Oromo at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

Orma at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

West Central Oromo at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

Waata at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024) - ^ a b Shaban, Abdurahman (2020-03-04). "One to Five: Ethiopia Gets Four New Federal Working Languages". Africa News. Archived from the original on 2020-12-15. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2759-2.

- ^ "Oromo". Dictionary.com.

- ^ "Oromo". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ^ Hodson, Arnold W.; Walker, Craven H. (July 1924). "Grammar of the Galla or Oromo Language". African Affairs (Review). XXIII (XCII): 328–329. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a100016.

- ^ Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D. "Oromo, West-Central [gaz]". Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-fifth edition. Dallas: SIL International. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ Bulcha, Merkuria (1997). "The Politics of Linguistic Homogenization in Ethiopia and the Conflict over the Status of Afaan Oromoo". African Affairs. 96 (384): 325–352. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a007852. JSTOR 723182.

- ^ "Oromo (Afaan Oromo, Oromiffa, Oromoo)". Language Centre Resources. University of Cambridge. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Oromo Language". MustGo. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "West Central Oromo". Ethnologue. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Ethiopia". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 6 June 2022.

- ^ "Amharic". Ethnologue.

- ^ "Oromo". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 2016-08-25. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ^ "Children's Books Breathe New Life Into Oromo Language". BBC. 16 February 2016.

- ^ "mcit.gov.et". mcit.gov.et. Archived from the original on 2019-11-19. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ "ቤት | FMOH". moh.gov.et. Archived from the original on 2021-02-05. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ^ Davey, Melissa (2016-02-13). "Oromo Children's Books Keep Once-Banned Ethiopian Language Alive". The Guardian. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ "Oromo" (PDF) (Brochure). National African Language Resource Center (NALRC).

- ^ "Ethiopians: Amhara and Oromo". International Institute of Minnesota.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2006-11-14). "The Afro-Asiatic Languages: Classification and Reference List" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-11-16. Retrieved 2022-06-08.

- ^ Janko, Kebede Hordofa (2012). Towards the Genetic Classification of the Afaan Oromoo Dialects. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89645-487-4.

- ^ "Languages of Somalia". Ethnologue. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "Languages of Kenya". Ethnologue. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "Languages of Ethiopia". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ Tutschek, Karl; Tutschek, Lorenz (1844). Dictionary of the Galla Language. Munich: L. Tutschek.

- ^ Smidt, Wolbert G. C. (2015). "A Remarkable Chapter of German Research History: The Protestant Mission and the Oromo in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). In Smidt, Wolbert G. C.; Thubauville, Sophia (eds.). Cultural Research in Northeastern Africa: German Histories and Stories. Frankfurt: Frobenius-Institut. p. 63.

- ^ Blair, Thomas Lucien Vincent (1965). Africa: A Market Profile. New York: Praeger. p. 126.

- ^ Lata, Leenco (1999). The Ethiopian State at the Crossroads: Decolonization and Democratization or Disintegration?. Lawrenceville, NJ: The Red Sea Press. pp. 174–176.Leenco Lata, The Ethiopian State at the Crossroads p.

- ^ Stroomer, p. 4

- ^ "Online Afaan Oromoo–English Dictionary". Jimma Times. 2009-04-15. Archived from the original on 2012-06-15. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ^ "Afaan Oromo". University of Pennsylvania, School of African Studies.

- ^ "Letter from the Oromo Communities in North America to H.E. Mr. Kofi Anan, Secretary-General of the United Nations". April 17, 2000. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2010 – via Oromia Online.

- ^ Hayward, R. J.; Hassan, Mohammed (1981). "The Oromo Orthography of Shaykh Bakri Saṗalō". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 44 (3): 550–566. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00144209. JSTOR 616613. S2CID 162289324.

- ^ "The Oromo Orthography of Shaykh Bakri Sapalo". The Abyssinia Gateway. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ Lloret (1997), p. 500

- ^ Dissassa (1980), pp. 10–11

- ^ called Qubee Dachaa in the Oromo language.

- ^ Owens (1985), p. 29

- ^ Owens (1985), p. 35

- ^ Owens (1985), p. 36–37

- ^ Owens (1985), p. 37

Bibliography

editGrammar

edit- Ali, Mohamed; Zaborski, A. (1990). Handbook of the Oromo Language. Wroclaw, Poland: Polska Akademia Nauk. ISBN 83-04-03316-X.

- Baye Yimam (1986). The phrase structures of Ethiopian Oromo. London: University of London. p. 347.

- Griefenow-Mewis, Catherine; Tamene Bitima (1994). Lehrbuch des Oromo. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. ISBN 3-927620-05-X.

- Griefenow-Mewis, Catherine (2001). A Grammatical Sketch of Written Oromo. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. ISBN 3-89645-039-5.

- Heine, Bernd (1981). The Waata Dialect of Oromo: Grammatical Sketch and Vocabulary. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer. ISBN 3-496-00174-7.

- Hodson, Arnold Weinholt (1922). An Elementary and Practical Grammar of the Galla or Oromo Language. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Lloret, Maria-Rosa (1997). Phonologies of Asia and Africa. Alan S. Kaye. ISBN 978-1-57506-019-4.

- Nordfeldt, Martin (1947). A Galla Grammar. Uppsala/Lund: Lundequistska Bokhandeln. p. 232.

- Launhardt, Johannes (1973). Guide to learning the Oromo (Galla) language. Addis Ababa: Cooperative Language Institute. p. 363.

- Owens, Jonathan (1985). A Grammar of Harar Oromo. Hamburg: Buske. ISBN 3-87118-717-8.

- Praetorius, Franz (1973) [1872]. Zur Grammatik der Gallasprache. Hildesheim; New York: G. Olms. ISBN 3-487-06556-8.

- Roba, Taha M. (2004). Modern Afaan Oromo grammar: qaanqee galma Afaan Oromo. Bloomington, IN: Authorhouse. ISBN 1-4184-7480-0.

- Stroomer, Harry (1987). A Comparative Study of Three Southern Oromo Dialects in Kenya. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag. ISBN 3-87118-846-8.

Dictionaries

edit- Bramly, A. Jennings (1909). English-Oromo-Amharic Vocabulary. Typescript in Khartoum University Library.

- Foot, Edwin C. (1968) [1913]. An Oromo-English, English-Oromo Dictionary. Cambridge University Press (repr. Farnborough, Gregg). ISBN 0-576-11622-X.

- Gragg, Gene B. et al. (ed., 1982) Oromo Dictionary. Monograph (Michigan State University. Committee on Northeast African Studies) no. 12. East Lansing, Mich. : African Studies Center, Michigan State Univ.

- Mayer, Johannes (1878). Kurze Wörter-Sammlung in Englisch, Deutsch, Amharisch, Oromonisch, Guragesch, hrsg. von L. Krapf. Basel: Pilgermissions-Buchsdruckerei St. Chrischona.

- Bitima, Tamene (2000). A Dictionary of Oromo Technical Terms: Oromo – English. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. ISBN 3-89645-062-X.

- Stroomer, Harry (2001). A Concise Vocabulary of Orma Oromo (Kenya): Orma-English, English-Orma. Köln: Rudiger Köppe.

- Gamta, Tilahun (1989). Oromo-English Dictionary. Addis Ababa: University Printing Press.

External links

edit- BBC Learning English Afaan Oromoo

- Online Oromo – Qubee Dictionary

- Voice of America news broadcast in Oromo.

- Oromo Federalist Democratic Movement (OFDM) website contains many articles written in Oromo and audio.

- PanAfriL10n page on Oromo

- HornMorpho Archived 2011-08-10 at the Wayback Machine: software for morphological analysis and generation of Oromo (and Amharic and Tigrinya) words

- 500 Word Oromo Dictionary

- Oromo – Daily News

- Google Translate adds 24 languages, includes Afaan Oromo, Tigrinya

- "Proposal for Encoding the Sheek Bakrii Saphaloo Script" (PDF). Unicode.