Ahu Akivi is a particular sacred place on the Chilean island of Rapa Nui (or Easter Island), looking out towards the Pacific Ocean. The site has seven moai, all of equal shape and size, and is also known as a celestial observatory that was set up around the 16th century. The site is located inland, rather than along the coast. Moai statues were considered by the early people of Rapa Nui as their ancestors or Tupuna that were believed to be the reincarnation of important kings or leaders of their clans. The Moais were erected to protect and bring prosperity to their clan and village.[1]

At Ahu Akivi, the moai face the ocean. Although the platform is clearly visible, the overgrown grass obscures the pattern of the sloping pavement. | |

| |

| 27°6′54″S 109°23′42″W / 27.11500°S 109.39500°W | |

| Location | Easter Island |

|---|---|

| Designer | Rapanui people |

| Type | Sacred stone statues |

| Material | Volcanic rock |

| Length | 70m |

| Height | 16 ft |

| Beginning date | Originally 15th century |

| Completion date | Restored in 1960 |

| Dedicated to | Make Make worship |

A particular feature of the seven identical moai statues is that they exactly face sunset during the Spring Equinox and have their backs to the sunrise during the Autumn Equinox. Such an astronomically precise feature is seen only at this location on the island.[1]

Geography

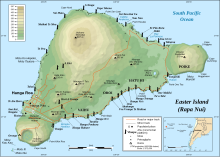

editAhu Akivi, aligned in an east–west direction,[2] is located on the flank of the southern slope of Maunga Terevaka at Rapauni and it is surrounded by fairly flat agricultural land. It is 2.3 kilometres (1.4 mi) inland in the non coastal zone and is at an elevation of 140 metres (460 ft). Ahu Vai Teka is at a distance of 706.8 metres (2,319 ft) from Ahu Kavi which is considered as part of the Ahu Akivi-Ahu Kavi complex.[3]

From Hanga Roa, an inland road leads to the site via the volcanic cone of Terevaka (510 metres (1,670 ft) peak level). The coast road is via Playa Anakena. On this road there are many moai statues lying scattered and un restored. There are paths branching off to Puna Pau, which is a quarry of low volcanic crater with red coloured rocks known as scoria, which has been used to carve 70 of the "top hat" of the statues known as pukao which could be cylindrical top knot of hair or grass hat or turban. Further on, the site of Ahu Akivi is reached.[4] The site is located to the Northeast of Hanga Roa,[5] the capital city of Easter Island, about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) to its north.[2]

The Rano Raraku quarry from where the statues were made is at least 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) away and free access is through the land route held by the clans.[3]

History

editAhu Akivi is part of the Ahu Akivi-Vai Teka complex which was built up by the Rapa Nui people in two phases. In the first phase, during the 16th century a central rectangular platform was created on a leveled surface. It had wings projecting to the north and the south directions. An approach ramp was also part of this platform which led to the ceremonial plaza stretching 25 metres (82 ft) towards the west of the central platform. A cremation ground existed behind the central platform. The second phase of construction was elaborately planned and implemented in the early years of the 17th century when the platform was modified, a ramp was created, seven statues of equal size were erected. Another crematorium was also built. A cave in which people used to reside was also used as tomb during historic times.[3]

The other Ahu in the complex is the Ahu Vai Teka, which is a much smaller platform of 16 metres (52 ft) length made up of rough lava stone blocks. There is no statue now, though one is believed to have existed initially. Both the ahus were believed to have been aligned astronomically with respect to the Sun. Both are located in the territory of the Miru, the highest ranking clan and the western confederacy, and both were contemporary. It is also conjectured that the seven statues were placed at Ahu Akivi at least 150 years before the first Europeans found the island when the clan was functional at that time. It is also evident that their culture existed for 250–300 years with economic prosperity with political stability.[3]

In 1955, Thor Heyerdahl recruited American archaeologist William Mulloy and his Chilean associate, Gonzalo Figueroa García-Huidobro, who later restored the statues to their original position; they had found them in knocked down condition in 1960.[1] Mulloy's work on the Akivi-Vaiteka Complex was supported by the Fulbright Foundation and by grants from the University of Wyoming, the University of Chile and the International Fund for Monuments. Ahu Akivi also gives its name to one of the seven regions of Rapa Nui National Park.[1]

Legend

editThe statues on the island invariably faced the village as a protective mana, but in the case of the Ahu Akivi statues they face towards the sea. There is a legend narrated for this positioning of the seven statues. It is conjectured that the Rapanui people did it to propitiate the sea to help the navigators. However, according to an oral tradition, Hotu Matu's priest had a dream in which the King's soul flew across the ocean when the Rapa Nui island was seen by him. He then sent scouts navigating across the sea to locate the island and to find people to settle there. Seven of these scouts stayed back on the island waiting for the king to arrive. These seven are represented by the seven stone statues erected in their honour.[6][2]

Features

editThe architectural features of an Ahu platform were discerned by archaeologists, depending on its length under five categories. These are: A central platform of varying length; platform made of crude masonry in its rear wall or with fine masonry in the rear wall; with or without wings; with one or more statues; a red scoria top knot (headgear), ramp, a crematoriums plaza pavement, crafted front retaining wall, a cornice made of red scoria. In the case of the Ahu Akivi all these features have been noted except that the rear part of the platform is made of crude masonry wall.[6] Another feature of the foundation of the platform is that the stones used to make it are not from the island but were brought as ballast in the 19th century in a ship.[2]

Apart from the above, archeologists also unearthed stone disks, small statues, and fish hooks made of stones and bones indicative of burial ceremonies that were performed at the site.[6]

The seven moai statues are located with absolute astronomical precision. Thus, the sacred observatory and sanctuary with all the seven moai look exactly towards the point where the sun sets during the equinox and which also aligns with the Moon. Each one is of 16 feet (4.9 m) height and weighs about 18 tons,[7] and its length is 70 metres (230 ft).[2]

During the excavations done here, the archaeologists also found tree root moulds, indicative of vegetative cover in the past.[5]

Restoration

editIn 1960, when the American archaeologist and his associate carried out restoration, it took them one month to rise and fix the first moai in place. They used a stone ramp and two wooden levers to carry out this operation. However, they took less than a week to raise the seventh one.[8]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d "Easter Island: stones, history. Easter Island". Lost Civilizations.net. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Ahu Akivi – The Seven scouts from Easter Island" (in German). Osterinsel.de. Archived from the original on 20 June 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d Peregrine & Ember 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Graham 2003, p. 537.

- ^ a b Flenley & Bahn 2003, p. 250.

- ^ a b c Kirch 1986, p. 73.

- ^ Maras 2010, p. 25.

- ^ "Ahu Akivi". NOVA Online and Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) Organization. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

Bibliography

edit- Flenley, John; Bahn, Paul (29 May 2003). The Enigmas of Easter Island. Oxford University Press, UK. ISBN 978-0-19-158791-7. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- Graham, Melissa (2003). Rough Guide to Chile. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-062-6.

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton (1986). Island Societies: Archaeological Approaches to Evolution and Transformation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30189-3.

- Maras, Drew Ryan (May 2010). Open Your Eyes: To 2012 and Beyond. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4389-8245-8.

- Peregrine, Peter Neal; Ember, Melvin (1 January 2001). Encyclopedia of Prehistory: Volume 3: East Asia and Oceania. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-46257-3.

- Spitzer, Daniel (13 December 2004). Let's Go Chile 2nd Edition: Including Easter Island. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-33560-1.

Further reading

edit- Mulloy, W.T. 1968. Preliminary Report of Archaeological Field Work, February–July, 1968, Easter Island. New York, N.Y.: Easter Island Committee, International Fund for Monuments.

- Mulloy, W.T., and G. Figueroa. 1978. The A Kivi-Vai Teka Complex and its Relationship to Easter Island Architectural Prehistory. Honolulu: Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

- Mulloy, W.T., and S.R. Fischer. 1993. Easter Island Studies: Contributions to the History of Rapanui in Memory of William T. Mulloy. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Mulloy, W.T., World Monuments Fund, and Easter Island Foundation. 1995. The Easter Island Bulletins of William Mulloy. New York; Houston: World Monuments Fund; Easter Island Foundation.

- Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the East Pacific, T. Heyerdahl, E.N. Ferdon, W.T. Mulloy, A. Skjølsvold, C.S. Smith. 1961. Archaeology of Easter Island. Stockholm; Santa Fe, N.M.: Forum Pub. House; distributed by The School of American Research.

External links

edit- William Mulloy Library Archived 2008-01-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Father Sebastian Englert Anthropology Museum

- Easter Island Foundation

- Rapa Nui Fact Sheet with Photographs

- Rapa Nui Photo Gallery

- The Statues and Rock Art of Rapa Nui

- University of Wyoming Outstanding Former Faculty

- Unofficial Easter Island Homepage

- Easter Island Statue Project

- Nova: The Secrets of Easter Island

- Easter Island – Moai Statue Scale Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- How to make Walking Moai

- Czech Who Made Moai Walk Returns to Easter Island