Amoebic brain abscess is an affliction caused by the anaerobic parasitic protist Entamoeba histolytica. It is extremely rare; the first case being reported in 1849.[2] Brain abscesses resulting from Entamoeba histolytica are difficult to diagnose and very few case reports suggest complete recovery even after the administration of appropriate treatment regimen.[1]

| Amoebic brain abscess | |

|---|---|

| |

| Amoebic brain abscess caused by Entamoeba histolytica | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Symptoms | Prolonged headaches, progressive Drowsiness, diminished upper limb movement, trouble swallowing, breathing difficulties, low-grade fever, and intestinal symptoms.[1] |

| Causes | Entamoeba histolytica |

| Diagnostic method | PCR based analysis of the CSF. |

| Treatment | Metronidazole. |

Signs and symptoms

editThe onset of symptoms is very abrupt and the disease progression is very rapid.[1] Hence finding the root cause of the symptoms is very important as failing to do so, could result in imminent death. Signs and symptoms include:[1]

- Prolonged headaches

- Progressive Drowsiness

- Diminished upper limb movement

- Trouble swallowing

- Breathing difficulties

- Low grade fever

- Intestinal symptoms

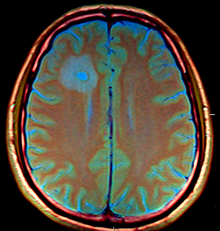

The CT images for the abscesses caused by Entamoeba histolytica are completely indistinguishable from the abscesses caused by any other organisms or causative agents. However, the brain abscesses are often observed in the frontal lobe or the basal ganglial regions.[1]

Immunopathogenesis of Entamoeba histolytica

editOnce the trophozoites undergo excystation in the terminal ileum region, they colonize the large bowel, remaining on the surface of the mucus layer and feeding on bacteria and food particles. However, in response to an unknown stimuli, trophozoites often move through the mucus layer and once they come in contact with the epithelial cell layer, they are able to start the pathological process. E. histolytica has a lectin that binds to galactose and N-Acetylgalactosamine sugars on the surface of the epithelial cells. The lectin is normally used to bind bacteria for ingestion. The parasite has several enzymes such as pore forming proteins, lipases, and cysteine proteases, which are normally used to digest bacteria in food vacuoles. However, these enzymes can cause lysis of the epithelial cells by inducing cellular necrosis and apoptosis when the trophozoites come in contact with them and bind via the lectin. This allows for penetration into the intestinal wall and blood vessels, sometimes leading to the liver and other organs like the brain. Meanwhile, the trophozoites begin to ingest the dead cells which triggers a massive immune response in the epithelial cell layer.[3][4]

The damage to the epithelial cell layer attracts immune cells, which in turn can be lysed by the trophozoite. This results in the release of the immune cells' own lytic enzymes into the surrounding tissue thus ultimately leading to excessive tissue destruction. This destruction manifests itself in the form of an 'ulcer', typically described as flask-shaped because of its appearance in transverse section. This tissue decimation can also involve blood vessels leading to bloody diarrhea or amebic dysentery.[3]

Occasionally, when the trophozoites enter the bloodstream, they are generally transported to the liver via the portal system. In the liver a similar pathological sequence ensues, leading to amebic liver abscesses. The trophozoites can also end up in other organs, as a result of liver abscess rupture or fistulas. In extremely rare cases, when the trophozoites travel to the brain surpassing the blood-brain barrier, they can cause amoebic brain abscess.[3]

Diagnosis

editThe diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica in the brain abscesses is difficult for several reasons. Firstly, the aerobic and anaerobic cultures generally provide negative results.[5][2]

In addition, the CT results are often inconclusive and even the parasitologic stool examinations and abdominal ultrasonography often yield normal results. However, direct examination of the abscess capsule may exhibit necrotic material, foamy histiocytes, rare eosinophills and ingested erythrocytes.[1] Spheric structures may insinuate the presence of Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites with Masson's trichrome stain. Additionally, PCR based analysis of the CSF can be used to positively identify the parasite in the system .[6]

Treatment

editMetronidazole is the first choice of drug for the treatment of the abscesses caused by Entamoeba histolytica. In addition, luminal amebicides such as Paramomycin must be administered after completion of Metronidazole treatment. This ensures complete eradication of the parasitic protist from the system.[7]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f Tamer, Gülden S.; Öncel, Selim; Gökbulut, Sevil; Arisoy, Emin S. (March 2015). "A rare case of multilocus brain abscess due to Entamoeba histolytica infection in a child". Saudi Medical Journal. 36 (3): 356–358. doi:10.15537/smj.2015.3.10178. ISSN 0379-5284. PMC 4381022. PMID 25737180.

- ^ a b Shah, AA; Shaikh, H; Karim, M (February 1994). "Amoebic brain abscess: a rare but serious complication of Entamoeba histolytica infection". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 57 (2): 240–1. doi:10.1136/jnnp.57.2.240-a. PMC 1072466. PMID 8126521.

- ^ a b c Kantor, Micaella; Abrantes, Anarella; Estevez, Andrea; Schiller, Alan; Torrent, Jose; Gascon, Jose; Hernandez, Robert; Ochner, Christopher (2018-12-02). "Entamoeba Histolytica: Updates in Clinical Manifestation, Pathogenesis, and Vaccine Development". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2018: 1–6. doi:10.1155/2018/4601420. ISSN 2291-2789. PMC 6304615. PMID 30631758.

- ^ Abdullah, Umme Hani; Baig, Mirza Zain; Azeemuddin, Muhammad; Wasay, Mohammad; Yakoob, Javed; Beg, Mohammad Asim (November 2017). "Amoebic brain abscess associated with renal cell carcinoma". Neurology and Clinical Neuroscience. 5 (6): 195–197. doi:10.1111/ncn3.12162. ISSN 2049-4173. S2CID 59205509.

- ^ Becker, George L.; Knep, Stanley; Lance, Kendrick P.; Kaufman, Lee (February 1980). "Amebic Abscess of the Brain". Neurosurgery. 6 (2): 192–194. doi:10.1227/00006123-198002000-00014. ISSN 0148-396X. PMID 6245387.

- ^ Ralston, Katherine S.; Petri, William A. (June 2011). "Tissue destruction and invasion by Entamoeba histolytica". Trends in Parasitology. 27 (6): 254–263. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2011.02.006. ISSN 1471-4922. PMC 3104091. PMID 21440507.

- ^ Chacín-Bonilla, Leonor (September 2020). "Editorial. Avances de la ciencia y perspectivas de las personas infectadas por el VIH en Venezuela". Investigación Clínica. 61 (3): 185–187. doi:10.22209/ic.v61n3a00. ISSN 2477-9393. S2CID 225180680.