The Spanish institutions of the Ancien Régime were the superstructure that, with some innovations, but above all through the adaptation and transformation of the political, social and economic institutions and practices pre-existing in the different Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula in the Late Middle Ages, presided over the historical period that broadly coincides with the Modern Age: from the Catholic Monarchs to the Liberal Revolution (from the last third of the 15th century to the first third of the 18th century) and which was characterized by the features of the Ancien Régime in Western Europe: a strong monarchy (authoritarian or absolute), a estamental society and an economy in transition from feudalism to capitalism.

Ancient Regime of Spain | |

|---|---|

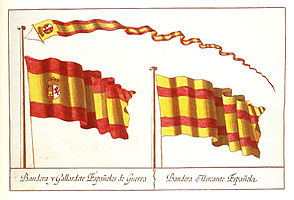

Symbols used by the institutions during the last years of the Ancien Régime. | |

| Date formed | circa 15th century |

| Date dissolved | early 19th century |

The characteristics of the Ancien Régime are dispersion, multiplicity and even institutional collision, which makes the study of the history of institutions very complex. The very existence of the institutional unity of Spain is a problematic issue. In this historical period there were unitary institutions: notably, and transcendental in the external perception of the Hispanic Monarchy, the person of the king and his military power; inwardly, the Inquisition. Others were common, such as those inherent to the estamental society: nobility, clergy and corporations of very different types were organized in a way that was not very different in each kingdom. A Catalan Cistercian monastery (Poblet) was interchangeable with a Castilian one (Santa María de Huerta); a Mesteño rancher, with another of the House of Zaragoza; the aristocracy merged into a network of family alliances. But others were markedly different: the Cortes or the Treasury in the kingdoms of the Crown of Aragon had nothing to do with those of Castile and León. Even with the imposition of Bourbon absolutism, which reduced these differences, the Basque provinces and Navarre maintained their fueros. The State and the nation were being forged, largely as a consequence of how the institutions responded to the economic and social dynamics, but they would not present themselves in their contemporary aspect until the end of the Ancien Régime.

Society in Ancient Régime Spain

editThe sociedad de la España moderna ("society of modern Spain" in the sense of the Modern Age or Ancien Régime) was a network of communities of diverse nature, to which individuals were attached by bonds of belonging: territorial communities in the style of the house or the village; intermediate communities such as the manor and the cities and their land (alfoz or comunidad de villa y tierra, of very different extension); political communities or broad jurisdictions such as the provinces, the adelantados, the veguerías, the intendancies or the kingdoms and crowns; professional communities such as corporations, fishermen's confraternities, or the universities; religious communities; etc.

The kingdom was contemplated with an organicist analogy, as a body headed by the king, with his supremacy, with the different communities and orders that formed it as organs, articulations and limbs. Men and women were linked by personal ties, such as family and kinship ties. Each bond was governed by common rules that were to govern its functioning and experience. In the Ancien Régime, communities were hierarchical, every body had its authority, and there were links of integration and subordination. But each link had an ambivalent value, of domination and paternalism: they had to guarantee the survival of individuals while maintaining social relations of subordination. What in the contemporary world are understood as public functions, were in the hands of private individuals, whether they were houses, lordships or domains of the king, with one territory having total autonomy from another. The very concept of private was meaningless, since there was no effective differentiation between public and private in the pre-state or pre-industrial society.

The nobility and the clergy were the privileged estates. From the 16th century onwards, the nobility tended to become more courtly and moved to Madrid, in the vicinity of the Court. The clergy was a more open estate, since individuals could join without regard to their social status, although it was also a hierarchical group with different degrees within its structure. The common state was the most heterogeneous and numerous. It ranged from the poorest peasants to the incipient bourgeoisie (the bourgeoisie of the intelligentsia: mostly literate people with administrative positions; and the bourgeoisie of business). The degree of integration of various persecuted minorities (Judeo-converts, moriscos or gypsies) underwent different alternatives.

Monarchy, nobility and territory

editThe way to determine the scope of royal power is to consider it as the reverse of manorial power and the inverse..... Manorial power never went beyond the exercise of local powers... the accumulation of lordships, however copious it was and even if it gave rise to the appearance of territorial manorial offices, never managed to extend its powers. Phenomena such as the sale of offices in manorial places but for the benefit of the Crown, or the well-documented fact of the appeal to royal justice, call into question the image of manorial power as a limitation of royal power.

Miguel Artola, Aristocracia, poder y riqueza en la España moderna: la Casa de Osuna, siglos XV-XIX, Prólogo.

The apex of the institutional system was the monarchy, justified from the beginning of the reconquista as an inheritance of the Visigothic Hispania in the Cantabrian nuclei: kingdom of Asturias, kingdom of León and county and later kingdom of Castilla; or of the Carolingian feudalism in the Pyrenees: Condal Court of Barcelona, later principality of Catalonia, county and later kingdom of Aragon, and kingdom of Navarra. This, in fact, had united almost all the peninsular Christian territories at the beginning of the 11th century, to later disintegrate them with the inheritance of Sancho III The Great among his descendants of the Jiménez dynasty, who were at odds with each other as they expanded territorially throughout Al-Andalus. By then the concept of hereditary monarchy was already sufficiently established to use it as a patrimonial institution, within the vassal dynamic of feudalism, with all the limitations that this expression has in the Iberian Peninsula. The European influence that arrived with the Camino de Santiago and the Order of Cluny determined that it was the House of Burgundy that would end up being linked to the western kingdoms (Portugal, León and Castile). The same justifying procedures (to which the very existence

of the monarchy was added) were used to justify the social predominance of the nobility (the bellatores or feudal defenders), who with the high clergy formed a single ruling class: the privileged.

The formation of the authoritarian monarchy culminated with the powerful Trastámara dynasty, originated in Castile in the person of a bastard, Henry II of Castile, raised to power by the high nobility who were zealous to avoid the same concentration of power, which would also be implanted in Aragon as a consequence of the Compromise of Caspe. The crisis of the 14th century had been decisive in producing a clear separation between the high and low nobility of hidalgos and knights, whose social prestige, when it could not be sustained by the control of lands, was sought with all kinds of probanzas, habits, ejecutorías, kings of arms, coats of arms ... which, if they could not be supported with those, did not hide their economic decadence. Geographically, there was also a gap between the north of the peninsula -the Cantabrian and Pyrenean mountains where the original lands of the noble houses were sought, but where there were no large domains and the greater equality of conditions allowed the myth of universal nobility to be born- and the south -dominated by the encomiendas of the military orders and the great noble estates-. For the non-privileged, there remained the perception of pride as an Old Christian, which was legally expressed in the statutes of limpieza de sangre, which were extended to all types of institutions after the anti-conversion revolt of Pedro Sarmiento in Toledo (1449). This legal discrimination was maintained as a decisive factor of social cohesion even more so after the expulsion of the Jews (1492) and the Moriscos (1609), maintaining as a useful scapegoat the existence of the New Christian, a condition from which neither the highest noble houses nor the king himself escaped (Libro Verde de Aragón, Tizón de la Nobleza).[1]

The territorial union of the Catholic Monarchs (by marriage: Aragon and Castile, or conquest: Canary Islands, Granada, Navarre, America, Naples, North Africa), was followed by the addition of vast territories in Europe with the arrival of the Habsburg dynasty, whose conception of power was based on respect for local peculiarities (not without conflicts, such as the Revolts of the Comuneros and the Brotherhoods with Charles V or the crisis of 1640 with Philip IV). The unitary conception of the peninsular domains allows historiography to speak of Hispanic Monarchy, despite the fact that the union is in the person of the kings and not in the kingdoms, which maintain their laws, languages, currencies and institutions. The attempt to unify them from the union of the noble families, especially in the foundation of the concept of Grandee (1520), which incorporated a small number of aristocratic houses of the two crowns (with clear Castilian predominance). Marriage alliances were encouraged, with the manifest aim that the social elite in practice was the same in all of them. The union with Portugal, which lasted sixty years (1580–1640), was also attempted to consolidate in the same way (not without misgivings; hence the Portuguese saying about Spain: "neither good wind nor good marriage").

Finally, the Bourbon dynasty (curiously, of Navarrese origin) will impose the French customs of absolute monarchy, not only in court protocol, but also in the centralist configuration of the State[2] and in the succession provisions of the Salic law, after a civil war with a European dimension: the War of the Spanish Succession.

The State of the Ancien Régime protected the interests of the nobility. Precisely for this reason, in addition to being absolute, it has been called by some authors – P. Anderson, Kiernan, Porshnev, etc. – as nobiliary or lordly. The monarch never questions his nobility, nor vice versa. The former is concerned with pampering the latter and maintaining its economic, social and other privileges. Naturally, this is in a general way, and seen as a long-term situation. Of course there are conjunctural conflicts. Hence, it is necessary to break with the cliché that the Catholic Monarchs put an end to the power of their nobility. It seems a methodological error to consider the beginning and development of the Modern State as the resolution of a conflict of interests between the monarch and the nobility, in which the Crown emerged victorious. The members of the high nobility were the first to be interested in having a strong central power that would enable social control and make it difficult, if not impossible, for the less wealthy social groups from which they obtained their rents to protest. The so-called Modern State protects, defends and consolidates the nobility's interests... On the other hand, it would be a serious error, very numerous among historians, to conceive its evolution in a linear way. Developments are not usually like that, but have their progress – an ethereal term – and their setbacks. The same is true of the function of the nobility and its role in the State. Shortly after the end of the Reconquest it forgets its military character, begins to act politically, with an intensity that finds its warmest point in the 17th century, and gradually its role is reduced to occupy exclusively diplomatic and honorary positions, both in the administration and in the Army, although this in a very general way, and as such quite distorting. Finally, it is necessary to banish the cliché that during the 19th century, the liberal State definitively cornered the nobility. This did not happen, among other circumstances, because their privileged economic situation was not significantly damaged. Much of our historiography is plagued by clichés that need to be refreshed.

Ignacio Atienza, "La nobleza en el Antiguo Régimen. Conclusión" (1987). 65–66.

-

Íñigo López de Mendoza, Marquis of Santillana, by Jorge Inglés. He could cross Spain from North to South sleeping every night in a castle of the wide family network (of Álava origin) of the Mendoza family, which he headed through the House of Infantado. He knew how to maneuver skillfully in the struggles between noble factions, opposing both the privation of Álvaro de Luna and the Infantes of Aragon, supporting King John II of Castile when it was most necessary, which allowed him to significantly increase his own political and territorial power. The Mendozas maintained their prominence in the following reigns, within the so-called humanist, ebolist, romanist or papist faction -opposed to the Albists-.

-

A century later than that of Santillana, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, third Duke of Alba (painted by Titian) belongs to a nobility whose highest aspiration is to figure in the best position in the service of an undisputed monarchy. Outstanding general of Charles V and Philip II, he was governor of Milan (1555), viceroy of Naples (1556) and governor of the Netherlands (1566), where the black legend painted him as a negative stereotype of the Spanish nobleman. Disgraced by a family marital affair, he returned to lead the armies in the Portuguese campaign (1580). The Alba family headed the imperial faction, albista, hispanista or castellanista - opposed to the ebolistas in the 16th century, and the ensenadistas in the 18th century.

-

No lesser lineage possessed the Valencian Saint Francis Borgia, painted by Alonso Cano with the Jesuit habit that he took in his maturity (he became General of the Society of Jesus). He contrasts, but does not deny the way of life of the high nobility: in the century he was Duke of Gandía (Valencian house with Grandeeship) and courtier of Charles V, who took him to his campaigns, married him to a Portuguese aristocrat and appointed him Viceroy of Catalonia. His famous vocation came to him in the truculent burial of Isabella of Portugal ("I will not serve any more Lord that can die").

-

Carlos Gutiérrez de los Ríos, Duke of Fernán Núñez, by Goya. He followed the family tradition of diplomatic service, attending the Congress of Vienna (1814), the swan song of the Europe of the Old Regime where Spain no longer had any relevant role. He was the last of his lineage to exercise jurisdictional dominion over the Cordovan town of his title. Unlike the French Revolution (in which the peasants dispossessed their lords), in Spain this did not mean the loss of property or the ruin of his house, which remains part of the aristocracy to this day.

The territorial conformation of the Hispanic Monarchy in such a wide range of territories allows us to speak separately of the American institutions, those of the European territories on the other side of the Pyrenees (especially Flanders and Italy) and those of the kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula, which are the subject of this article.

The latter can be understood as an institutional unity (with the clear exception of the Kingdom of Navarre and the Basque provinces) from the beginning of the 18th century, due on the one hand to the traumatic clarification brought about by the separation from Portugal (1640), and on the other hand, the Nueva Planta decrees (1707 to 1716) which reduced the legislation of the Crown of Aragon to that of Castile (which was decisive above all for Catalonia, Valencia and Mallorca, since the Kingdom of Aragon had seen its charters very limited as a consequence of the revolt of Antonio Perez in 1592). In any case, and in spite of being used at the time, the expression kingdom of Spain and the concept of national unity (of liberal origin) should not be used strictly prior to the Constitution of Cádiz of 1812, already in the New Regime. It is not the object of this article to define Spain as a nation, but it is necessary to emphasize that the Spanish national identity is constructed precisely as a consequence (sometimes in spite of them) of the prolonged existence in time of the institutions of the Ancient Regime, some unitary, others common and others plural in their territorial configuration. When the Cortes de Cádiz held their debates, an explicit attempt would be made to update the traditional institutions which, together with the uses and customs, would supposedly form a "constitution" of their own, natural, timeless, adequate to the Spanish national idiosyncrasy,[3] despite the fact that the Constitution of 1812 was clearly a revolutionary rupture. Another thing would be to elucidate the pre-existence of a national character or "Ser de España", as it was understood in that famous essayistic debate.

The Municipality, the Courts and the Treasury

editIn the absence of powerful intermediate levels of territorial organization (they existed, but in a discontinuous manner, and sometimes without competencies or resources that would make them decisive: adelantamientos, veguerías, merindades... until the Bourbon reforms introduced the network of army and provincial intendants, precedent of the provincial governor), the lower level of territorial organization presented in Spain an extraordinary vitality: the municipal institution, inherited from the Roman municipality and reinforced with the repopulation that followed the reconquest during the Middle Ages. The early medieval repopulation process had granted an original freedom unparalleled in other parts of Europe (presuras, allods, behetrías), and more than in any other kingdom in the Castilian frontier or Extremadura, where the status of peasant was equated to that of nobleman if he defended his own land with a war horse (Caballeros Villanos). With the passing of the centuries and the distancing of the frontier, the concejos abiertos of the first moments, in which all the neighbors participated, were substituted by powerful corporations, the councils or town councils of cities or towns with "fueros", "cartas pueblas" that granted them jurisdiction over a wide "alfoz" or "comunidad de villa y tierra", composed of numerous rural nuclei (towns, lugares and villages) and more unpopulated lands (mountains, pastures, meadows, wastelands) against which they behaved as a true "collective lordship", in a similar way to how nobility and clergy were forming their own lordships. The condition of the peasants, therefore, was not radically different in royalty and manor: neither in the former was freedom nor in the latter slavery.

-

Salón de Cent (for the former Consell de Cent or Consejo de Ciento) of the Barcelona City Council.

-

Pamplona City Hall.

-

Avilés City Hall.

-

Alcañiz City Hall.

The involvement of the royal authority in municipal control became stronger at the end of the Middle Ages, as the monarchy became more authoritarian, especially after the crisis of the 14th century. Finally, a sort of "distribution of roles" took place between the regidores, who had become venal and in practice hereditary positions in the families of what can be called urban patricians or municipal oligarchy (ennobled knights or bourgeois, ciutadans honrats (catalan for "honored citizens"...)[4] and the corregidor, as the direct representative of the king in the municipality. In smaller municipalities, the posts were usually held by a mayor representing the common state and a mayor representing the nobility.

The most important municipalities were the cities with a vote in the Cortes,[5] representatives not so much of a third estate as of an ennobled urban patriciate, more so in Castile than in Catalonia, where the city of Barcelona had a fundamental weight and from 1359 the permanent deputation of the Cortes (the Generalitat) acted as an effective counterweight to the increase in royal power; or in Aragon, where they were presided over by the Justicia (who warned the kings "We make you King if you comply with our Fueros and enforce them, otherwise not"), in addition to having its own Diputación del General since 1364. A similar institution existed in Valencia since 1418.

The Cortes were the representative institution of the kingdom (entity dialectically opposed to the king), with legislative and fiscal functions; stronger in Aragon, where they maintained their structure in three arms (four in the kingdom of Aragon, with the nobility divided into rich men and hidalgos), weaker in Castile, where they ceased to convene the privileged estates. They lost importance precisely in the XVIII century, when those of both crowns were summoned jointly, but they would only meet for succession issues.

There were three instances with independent fiscal capacity: the Church, the Kingdom and the Crown. Ecclesiastical taxation consisted in the collection of tithes and first fruits, direct taxes levied on the income from the land.... The Church, which, because of its pastoral function, had its individuals distributed throughout all the places, was in a position to demand a tribute of this type, things that the crown could not do.... The Cortes of each kingdom had limited powers in the legislative process – they formulated petitions that the king granted, postponed or denied – and decisive powers with regard to the voting of services. At the beginning of the sessions, the king or his representative presented the most significant points of his foreign policy and requested a service or donation that was usually fixed after often laborious negotiations, and only on one occasion, the Catalan Cortes of 1626, was the service not voted on, due not to the refusal of the procurators but because the sessions did not conclude.... The royal treasury lacked unity. Each kingdom constituted an independent administration and in all of them, with the exception of the budgets of the Kingdom in Castile, the principle was applied of consuming all the resources obtained in the territory... there was no treasury unity until 1799, when the so-called "reunion of revenues" was established.

Miguel Artola, "La Hacienda del Antiguo Régimen" (1982) 13–16.

The treasury was one of the pillars of the functioning of the Monarchy, much more substantial in Castile than in Aragon and Navarre (and in the Basque provinces, which, although Castilian, possessed a tax exemption linked to a hazy universal nobility). The Chamber of Comptos of Navarre or the private institutions of the other territories did not collect more than what was necessary to maintain the functioning of a minimum bureaucratic apparatus of their own, being insufficient even for the defense of the territories themselves if necessary. The same can be said of the more substantial revenues of Flanders or Italy (in these cases faced with constant and substantial military expenses). For Castile, the undisputed fiscal center of the monarchy, the Treasury Council and the Cortes designed the system, but it was really based on headship by the cities, for their benefit and against the territory they administered, and its actual collection – based on sisas levied on consumption and mercantile traffic – was usually leased to private individuals.[6] The main revenues were always insufficient, so that the extraordinary emergency resources to loans from bankers (successively Castilian, German -the mythical Fugger-, Genoese and Portuguese) to the public debt (juros) and to monetary alterations were a chronic burden, which undermined the monarchy's credit and led it to periodic bankruptcies.[7] These revenues were mainly the quinto real of American metals (which altered the economy of Europe producing the Price revolution)[8] and the alcabala, a theoretically universal indirect tax. The multiplicity of royalties and other taxes (ordinary and extraordinary service, millones, regalías de aposento, etc.) made the system inefficient and unfair, which led to some failed attempts at reform, such as the Union of Arms designed by the Count-Duke of Olivares and the Single Tax linked to the Catastro of Ensenada. Prior to this, the Nueva Planta decrees had administratively unified Valencia and Catalonia without any difference with Castile (Aragon had already lost its fueros in the time of Philip II of Spain after the revolt of Antonio Perez), as a consequence of its defeat in the War of the Spanish Succession, which gave the opportunity to establish a tax system practically ex-novo without the obstacles of having to respect acquired rights, resulting in a simple and effective system that in fact stimulated economic activity during the 18th century while producing a substantial increase in tax collection. This fiscal ideal, added to other legal characteristics (the emphyteutic census that guaranteed the Catalan peasant the continuity of his agricultural exploitation, and the survival of civil law, which guaranteed the hereu (inheritor) the full conservation of the family patrimony) was a model of the Enlightenment reforms (Count of Campomanes) although the resistance encountered made its application in Castile unviable, in what can be seen as an inverse situation to that of the Count-Duke's Union de Armas of the previous century.

Economic life

editEconomic life depended only very partially on high-level political decisions, despite the fact that the mercantilist orientation of the monarchy's economic policy (judged by the arbitrists, founders of economic science) was very pronounced. In the Crown of Aragon, medieval institutions such as the Llotja and the Taula de canvi, as well as the Consulate of the Sea and Commerce Consulate (also present in Castile), presided over long-distance trade, which, with the colonization of America, it became vital to control. This function was monopolistically entrusted to the Casa de Contratación in Seville. A similar institution was even envisaged, which would have operated in La Coruña, to control the expected spice trade with the Maluku Islands, but the cession of these islands to Portugal frustrated it. The freedom of trade with the Americas was one of the issues that the enlightenment policy of the 18th century tried to develop, opening the monopoly (then exercised by Cadiz) to other peninsular ports (1788), after the development of chartered companies such as the Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas (1728), later transformed into the Royal Company of the Philippines (1785).

In a narrower way, it was the municipal institutions that controlled the crafts and local commerce, through municipal ordinances. These relegated the control of the operation of the vile and mechanical trades to intermediate corporations that were self-managed: the corporations, associations of workshops of the same trade whose essential functions were to avoid competition among their members, control access to professional practice, maintain quality standards and the know-how of the trade (even against technological innovations), integrate and order in a paternalistic way the different professional categories (master, journeyman and apprentice) and defend their interests in a protectionist way (against intrusion, foreign competition or even economic and fiscal political interference, acting as a pressure group if necessary). They never had as much vitality as in other parts of Europe. In Castile, the inland cloth cities, such as Segovia or Toledo, did not manage to impose protectionist measures that would allow them to develop their industry in the face of consumer protection and the livestock and export interests of the peripheral cities, such as Burgos and Seville.[9] Municipal ordinances also controlled trade through markets of regional dimension; and with institutions such as the Repeso or the Fiel almotacén, whose function was to control supply, food trade and the agents of trade, such as the obligados and tablajeros.[10]

Fairs such as those of Medina del Campo,[11] which connected Castilian wool with the financial economy of northern Europe, represented an exceptional activity, which included the emergence of financial institutions and families of bankers that did not have continuity. The business opportunities offered by the American market, the enormous debt of the Treasury and the successive economic situations of inflation in the 16th century (Price revolution) and depression in the 17th century, rather than providing incentives, ended up asphyxiating the Castilian economic agents to the benefit of those from other European countries. Despite their importance, they did not serve to integrate a national market. Nor did the maintenance of internal customs, currencies and legislation specific to each kingdom help in this regard. The Crown of Aragon did not participate in the American commercial enterprise until the 18th century, although since then, especially in Catalonia, it was possible to witness the growth of a textile industry for the colonial market (the Indianas), stimulated by especially favorable social conditions, as evidenced by the appearance of a dynamic local institution: the Real Junta Particular de Comercio de Barcelona (1758–1847).[12]

The fact that most of the population depended on self-sufficiency (the peasants) or on their own rents (nobles and clerics) meant that trade was, in reality, a somewhat marginal activity. Other vaguely pre-capitalist institutions, such as the Mount of piety or the Bank of St. Charles arrived later, at the end of the Ancien Régime, although they had earlier precedents in traditional figures that were able to adapt to the expansive situation of the 18th century, such as the Pósitos, the Five Major Guilds of Madrid or the corporations of arrieros (arrieros of Sangarcía and Etreros in Segovia, and that of Maragatería in León), highlighting the carretería or Cabaña Real de Carreteros, trajineros, cabañiles and their derramas (founded with privileges in 1497, and with special jurisdiction since 1599, including a conservator judge to defend them).[13] The Royal Manufactures, as an adaptation of the Colbertist economic policy, were the work of the Bourbons, but there was also an earlier interest in the control of strategic industries (armament factories and the Royal Shipyards).

It was the countryside, agricultural activities, which constituted the overwhelming majority of the economy in pre-industrial society. Primary food production depended on an agriculture subjected to traditional processes sanctioned by custom and the uses of the feudal regime, in charge of peasants whose social situation sometimes led to revolt (Irmandiño revolts in Galicia, pagesos de remença in Catalonia), with the monarchy playing an arbitration role (Sentencia Arbitral de Guadalupe) that did not hide its preference for maintaining the privileged status of the nobility and clergy (legislation on the Majorat).[14]

This option is clearly seen in the protection of cattle raising over agriculture, which has been understood by historiography as a class struggle between lords (ranchers) and peasants (farmers). The Mesta in Castile and similar institutions in the kingdom of Aragon (Casa de Ganaderos de Zaragoza) became very powerful privileged corporations, with privative jurisdiction, in which the norm was the confusion of interests and jurisdictions between the public and the private. The Enlightenment critique found in their survival one of the most important obstacles to economic modernization, together with the lack of definition of property rights (entailments and mortmain) and the obstacles to the free market (Pacte de Famine, internal customs and fiscal atomization). This period will be presided over by the Enlightenment project and the diffusion of the model of Sociedades Económicas de Amigos del País, born in the Basque Country and with special projection to Asturias, Madrid, in both places with the presence of Jovellanos, who also contributed to the Expedient of the Agrarian Law, another project born of the Enlightenment restlessness that emerges from some positions of the administration, in this case of the Intendant of Extremadura.

Bureaucracy, justice and legislation

editThe central bureaucracy was based on the system of Councils, which has been called polysynodial, because it was composed of multiple bodies that divided the government of such a complex monarchy thematically and territorially. There were thematic and territorial councils: Treasury, Orders, Inquisition, Indies, Flanders, Italy, Portugal, Navarre, Aragon, etc. The Council of Castile was responsible for most of the domestic policy, especially from the 18th century onwards, and the Council of State for international relations. The Chamber of Castile, a reduced commission of the council, but separate from it, was in charge of advising the king, as a secret and reserved office, in the administration of the royal grace or merced, a legal concept proper to the power exercised by kings by their mere will. The juntas were committees assembled for a monographic matter (although the local government institutions of the territories of the Cantabrian area (Galicia, Asturias and the Basque Provinces) were also called juntas.

The king's personal work at the head of such a vast complex could be undertaken by a vocational bureaucrat like Philip II of Spain, who spent half his life among papers (hence his nickname of "paper king"), or entrusted to the figure of a favourite.

With the reforms of Philip V, the councils declined (with the exception of the Council of Castile), and it was the Secretariat of State and the Office that became the most important institution in the governmental structure. First as the Secretariat of the Universal Office, since 1705 divided in two, and since 1714 in four (State, Treasury, Justice and one for War, Navy and the Indies), precedents of the structure in ministries and Council of Ministers with a President that will be typical of the Late modern period.

In any case, the work of the Secretaries who carried out the daily management of affairs had always been essential, and led to the formation of a class of scholars that allowed social ascent from non-privileged positions (or more commonly the lower nobility). Such a thing provoked not a few envies and misgivings among the grandees (whom the testamentary advice of some kings to their heirs recommended to be close to the Court and in diplomatic or military missions, but away from positions in which they could rule by themselves). At the same time, it guaranteed to the kings the fidelity of those who were their "breeds" and who should have no other ambition than to keep the favor of the king who had raised them to the throne. In a society in which family origin, and not merit or work, is the justification for social position, they could never have aspired to so much on their own. Positions of that nature existed, as it is logical, since the late Middle Ages, and some royal secretaries (several of Basque origin) reached a high confidence of the kings who did not delegate in favourites: Juan López de Lezárraga, that of Isabella the Catholic; Francisco de los Cobos and Martín de Gaztelu, among those of Carlos V; Mateo Vázquez de Leca, Antonio Pérez and Juan de Idiáquez of Felipe II.

The social role of these and other officials was somewhat similar to that of the French Nobles of the Robe, which had judicial functions. Traditionally it has been proclaimed with undisguised pride that in Spain the administration of justice did not come to have venal offices as in France, but in any case for a large part of the territory it fell under the manorial jurisdiction (which could be sold, with the manors).

The royal estate was judicially administered with a structure that began in the municipalities. Regidores and mayors were true judges, as well as legislators and executive power at the local level (the separation of powers was inconceivable, both at high and low levels); and bailiffs were justices, assisted by notaries, as in any court. The Spanish taste for writing down every administrative act produced such an extensive volume of documentation that it has been exploited by hispanists from all over the world, in a kind of reverse brain drain, since they could not find similar deposits in their countries of origin. The documentation produced by the royal dispatches soon reached such a volume that it could not accompany the itinerant court, and Charles V ordered the creation of the General Archive of Simancas. Similar accumulations of administrative acts of the town councils and parishes allow Spanish local history to have an inexhaustible corpus of documents. Imagine the result of adding to all this the hundreds of archives of notarial protocols, a daily reflection of the activity of all social institutions through all kinds of writings, deals and contracts[15] (marriages, dowries, wills, properties, titles, majorats, sales, mortgages, censuses...) that sought in the public registry of the notary the legal security provided by the liturgy of the written word and the stamped paper (a Spanish invention soon imitated in Europe). The stage in which the Spanish economic-social formation was at each moment found in these institutions the catalyst that accelerated or slowed down the rhythm that the productive forces were imprinting on their particular transition from feudalism to capitalism during the Ancien Régime.

For the Crown of Castile, the highest courts were the Reales Audiencias y Cancillerías of Valladolid and Granada (the latter being heir to that of Ciudad Real), created by delegation of the jurisdictional competence of the king, which in the Late Middle Ages was exercised by his own audience, itinerant like himself along with the papers and officials of the Court, and which became two stable institutions that divided the territory (with a border on the Tagus river) in the reign of the Catholic Monarchs. During the Modern Age other audiences were created (without title of chancillerías and subject to the jurisdiction of these) of Galicia, Asturias, Extremadura and Seville, in addition to the American ones.

The Court had a special jurisdiction: the Sala de Alcaldes, also itinerant until the establishment of Madrid as capital (1561), which conflicted with the ordinary jurisdiction of the place where it resided and a certain number of leagues around it. A priority was established for this (as well as for the Audiencia or Chancillería in its territories, as an emanation of the royal power) in the so-called casos de corte. Once the Court was established, the jurisdictional conflicts were mainly with the Villa de Madrid.

For the Crown of Aragon, the judicial plant also included the figure of the Real Audicencia.[16] The legislation of the territories of this crown, as well as in the Basque provinces and the kingdom of Navarre (which had the Royal Council of Navarre as a judicial institution) was always less permissive for the royal power, and did not disappear completely with the Nueva Planta decrees, nor with the abolition of the foral regime after the Carlist Wars. At present it still survives (to a different degree in each territory) as foral law, very important in some civil law matters, and even in the conformation of the so-called historical rights of the so-called foral communities.

The sources of law in the different Christian peninsular kingdoms were very different, although the memory of Visigothic legislation (Liber Iudiciorum) remained a constant, both to justify the power (kingdom of Asturias and Leon) and to reject it (County of Castile, which was born burning its copies and preferring the customary law applied by the Judges of Castile, through the fazañas).[17]

In Catalonia there was a very important legislative activity in the Middle Ages, compiled in the Usages of Barcelona and in the Catalan constitutions, which maintained pacitist formulations typical of the Aragonese crown. Similar principles were applied in the Furs of Valencia and the Franquesas of Mallorca. The litigious and interpretative activity of this legislation produced an inexhaustible source of work for the jurists of the Crown of Aragon throughout the Ancien Régime, and up to the present day.[18]

Legislative codification gave the Crown of Castile greater powers to the king, in a process of construction of the authoritarian monarchy in which Roman jurists introduced jus commune ("common law" with a Roman-canonical basis), in conflict with the traditional fueros, granted locally to encourage repopulation (Fuero de Sahagún, Fuero de Logroño, Fuero de Avilés) or more generically as estamental privileges (Fuero Viejo de Castilla, Ordenamiento de Nájera). This process began in the late Middle Ages with the code of Siete Partidas of Alfonso X the Wise, and was accentuated with Alfonso XI (Ordenamiento de Alcalá) and the Catholic Monarchs (Leyes de Toro). In the early modern period, the process continued with successive reformulations (from the Nueva Recopilación to the Novísima Recopilación). The Spanish colonization of the Americas was the object of a special legislative care (Laws of the Indies) for which a peculiar support of jurists and theologians was requested (Laws of Burgos, Valladolid debate), since the justos títulos of the Conquest depended on the interpretation of the Alexandrine Bulls that the Pope granted to the monarchs. The American institutions were based on the Castilian ones, although reinterpreted and adapted to their ultraperipheral situation (municipal cabildos, audiences, captaincies, governorates, corregimientos, viceroyalties, Real Acuerdo, juntas).

The army, the navy and the Santa Hermandad

editThe basic instrument of the authoritarian monarchy was the permanent and professional army, made up of soldiers of any nationality (some merely mercenaries and others who sought their cursus honorum in the profession of arms). The medieval concept of feudal huestes, summoned sporadically for a limited campaign and then disbanded, which limited the power of the feudal monarchy to its ability to maintain the loyalty of its vassals, who were also to be rewarded with the conquered lands, was overcome. The War of the Castilian Succession, besides clarifying the dynastic union with Aragon and not with Portugal, made it clear that the only opportunity to maintain the authority of a king was his control of a military instrument at his exclusive service that could keep the nobles and cities in check, the better if it was so expensive that only by pushing the resources of the monarchy's treasury to the limit could it be paid for. The weapon of artillerywas a very useful technological innovation for this purpose: the noble castles and urban walls would cease to be insurmountable obstacles. The War of Granada was the field of experimentation of this new mechanism, which will receive the name of tercios (from 1534, from the captaincies and colonelships of previous times) and will represent the decisive advantage against the French monarchy in the Italian Wars. The traditional title of Constable of Castile – since 1382 the head of the armies, replacing the old position of ensign – was linked to the Fernández de Velasco family (Duke of Frías) and will play a more protocol role from the 17th century onwards. When the military function of the nobility was already an inoffensive memory, in the times of Philip II, it was again considered to be part of the Maestranzas de caballería, which, like the Military orders, fulfilled a military function while at the same time endowing its members with an undeniable estates prestige. The substantial thing happened in other scenarios: the continuous wars in Europe kept the tercios as a well-oiled machinery for large amounts of money -and terribly unpredictable when it was lacking: sacks of Rome and Antwerp-. Control of the Spanish Road between Italy and Flanders allowed the Hispanic Monarchy to use them to the benefit of its policy of defending Catholicism and Habsburg hegemony until the battle of Rocroi.[19]

The same thing that happened with the position of Constable occurred with the title of Admiral of Castile, which in the Middle Ages was in charge of the Navy of Castile, and which ended up being linked to a noble family (the Enríquez family, since 1405) and ended up being honorary. The Capitulations of Santa Fe granted Christopher Columbus and his descendants the title of Admiral of the Ocean Sea together with the viceroyalty of the lands to be discovered, but the recovery for the monarchy of the effective management of those functions was a matter of a few years. Similar procedures were used with the so-called conquests in the American territory, an extension of the medieval cavalcades, and which in practice were political-military subcontracts to a particular of the rights that the monarchy was obsessively concerned with maintaining and justifying (the justos títulos and the reading of the famous Requirement). The Spanish treasure fleet was the most important organizational challenge to which any empire had ever been subjected – the Spanish and Portuguese were the world's first oceanic empires – and the success of its protection by galleons was proven by the fact that only one of the convoys (that of 1628, by the Dutchman Piet Hein) was captured among hundreds. The protection of the coasts on both sides of the Atlantic, of an inabarcable extension, against the maritime powers and piracy was also effective seen in perspective, in spite of the punctual failures (Pernambuco, Cádiz, Gibraltar...). The Mediterranean galleys and the fortified presence in the African presidios (Ceuta, Melilla, Oran...) were the instruments of control of the other space of geostrategic interest, in which the enemy was the Ottoman Empire and Berber piracy.

Internal public order was in the hands of the local justices: manorial or urban, and their dispersion was the norm. The rollo or pillory was the symbol of the exercise of jurisdiction, and its presence at the entrance to the towns indicated this, as well as being used to carry out the penalties of death or public shame. The social ideal of expeditious justice was reactivated with each episode of delinquency that struck the imagination, especially crimes that altered the urban pax. The night patrols sought, more than to avoid them, to make present the existence of a vigilance. Crimes in unpopulated areas were much more difficult to prevent and more punished. The Santa Hermandad was a militia of cuadrilleros managed by the Castilian town councils (similar to the Catalan somatén), which came to be controlled by the monarchy in the time of the Catholic Monarchs. Brigandage -including that of the rural nobles- did not disappear, and the mechanisms to combat it did not reach the mountainous areas -Sierra Morena, areas of Catalonia or Galicia- until the repopulation of some of them was developed (Olavide's program for Sierra Morena). Its survival in the 19th century was the object of attraction of a curious romantic "tourism".[20] There was no police force worthy of the name until Ferdinand VII, who used it as an agency of political repression, and later even the Civil Guard (1844), which inherited many characteristics of the Santa Hermandad, such as territorial deployment with a preferably rural vocation. Curiously, the only security corps in existence today that derives from the Ancien Régime is the Mossos d'Esquadra, recovered by the Autonomous Community of Catalonia, which was created as Escuadras de Paisanos Armados on 24 December 1721, with a rather inautonomist purpose: to maintain public order in substitution of the somatén and to put an end to the strongholds of miquelets supporting Charles of Austria.[21]

Just as it is impossible to find in the Ancien Régime a separation of powers such as that described by Locke or Montesquieu, the pretension of a unitary exercise of power meant that the military organization in the territory could be identified with the civil order to such an extent that there was no difference whatsoever between the positions in both spheres. The most complete example came with Bourbon absolutism, in the figure of the intendant of the army and province, subject to the eleven Captaincy Generals. However, before these figures could be implemented, it was necessary to wait for the disappearance of the particularism of the kingdoms of the crown of Aragon, which did not admit the king's capacity to order the presence of troops at will -which was at the origin of the uprising in Catalonia (1640)-. Similar peculiarities were maintained in the Basque and Navarrese foral territories. Also in the 18th century, while the program of the Marquess of Ensenada rebuilt a navy capable of maintaining itself in the arms race with France and England until Trafalgar, a structure was created in three maritime departments: the Mediterranean or Levant, based in the Cartagena Naval Base, and two for the Atlantic, the one in Cádiz and the one in Ferrol.

The Royal Artillery School of Segovia, installed in the Alcazar, was a scientific institution of the first order. Mathematics, calculus, geometry, trigonometry, physics, chemistry, artillery and fortification studies, laboratory, scientific-military library. "There was no lack of books or money to buy them" said Count Félix Gazola. Its own editorial production of books for teaching, translation of scientific works and of course applied empirical research, were some of the subjects and activities that distinguished the school, protected by the Crown, and turned it into the most important teaching center in Spain in the last third of the 18th century, corresponding to and at the level of the prestigious international scientific institutions with which it was related.

In the time of Charles III and under the government of the Count of Aranda, a series of institutions were founded that would have great projection in the Contemporary Age, some symbolic: the Marcha Real (which would become the anthem of Spain) and the red and yellow banner (which replaced the white one with the Burgundy cross of St. Andrew in the Navy and ended up becoming the flag of Spain); and others substantive: the Royal Ordinances (Reales Ordenanzas para el Régimen, Disciplina, Subordinación y Servicio de sus Exércitos, of 22 October 1768)[22] and the extensive regulation of compulsory conscription by drawing quintas (1770),[23] an evolution of the already existing one, derived from the system of the Santa Hermandad (which obliged each town or group of towns to distribute one soldier for every one hundred inhabitants). The privileged were exempted, and the Basque provinces and Navarre participated in this privilege (which produced a curious emigration of midwives from neighboring provinces). However, the formation of something that could be called a national army, similar to the revolutionary army of France, had to wait for the popular uprising of the Spanish War of Independence.

The Church, the teaching and the Inquisition

editThe Church in the Catholic Monarchy was an institution distinct but not separate from the civil power, which served and used it at the same time: the achievement of the "religious maximum" at the end of the fifteenth century, which justified the expulsion of the Jews and the forced baptism of the moriscos,[24] does not deny its usefulness for internal social control, and has sometimes been explained as the result of a class struggle masked as an ethno-religious conflict.[25] The European policy of the Habsburgs, and Philip II's statement "I would rather lose my states than rule over heretics" was not only a senseless bleeding to death for the benefit of the Catholic faith, but a chain of tactical and strategic responses that fall within the imperial logic.[26] Church-State relations, which gave rise to the birth of diplomacy at the end of the Middle Ages, were not established without conflict: the regalism or predominance of the Catholic Monarch over the Church within its borders always presided over its relationship with both the local church and the Pope, who had in the Apostolic nunciature much more than a simple embassy (he extracted notable revenues and exercised great political as well as religious influence). On the other hand, the interference of the hegemonic power -Spain- in Rome -center of international relations- was constant: from the preparation of the conclaves (in which sometimes candidates as clear as Adrian of Utrecht, preceptor of Charles V, were imposed) to the invasion (sack of Rome in 1527), passing through the punctual alliances in favor (Holy League of 1511 and 1571), or against (League of Cognac in 1526). The political control of the clergy went beyond simple collaboration: the appointment of bishops obtained through the right of presentation, participation in ecclesiastical revenues (the royal third of the tithe, a tax more important than any of the civil ones) and, already in the 18th century, pressure on their properties (the so-called "first confiscation"). In America, the Alexandrine Bulls made the control even greater.

Proof of the deep religiosity that is supposed to the Catholic Monarch was the extreme importance that was granted to the election of the royal confessor, a real power in the Court for his capacity of access to the person of the king (sometimes considered little less than a favourite), and that it was customary to appoint among the members of a religious order (successively Franciscans, Hieronymites, Dominicans, Jesuits...). ) interpreting the appointment of a new confessor as an act of government of the first order, whose meaning could be analyzed in political terms as an expression of the confidence that the king deserved from one faction or another, serving as a channel of discrepancy (in a different way, but parallel to how the different political parties related to the king in a non-democratic parliamentary monarchy).

The influence of the royal confessors was only one aspect of the enormous prestige enjoyed by the Church, perhaps the most powerful of the pressure groups, according to today's terminology. But its authority was more social than political. It defended its interests and exemptions, even the less justifiable ones; however, in its clashes against an unpopular civil power it usually had the sympathies of the people. Some preachers criticized the actions of the rulers; not a few tried to influence them with their writings; more than one obtained important positions.... It is enough to remember the main role played by Cardinal Portocarrero in the struggles for the succession. But the Church, as a hierarchical body, did not have a defined political action.

— Antonio Domínguez Ortiz, "Sociedad y estado en el siglo XVIII español" (1976), p. 17.

As for the rest of the administration, the clergy (who remained, as in the Middle Ages, the most educated segment of the population) was used extensively: from the presidency of the Council of Castile, which was systematically entrusted to a bishop, to the requests for statistical information addressed to the parish priests.

A perfect society, according to its own theology (political Augustinianism), the Church was inextricably united as an institution with the society of the estates: clergy and nobility are the same class, the privileged, and the justification of the social and economic predominance of both against the bourgeoisie and peasants is a clear and consciously worldly part of its spiritual mission. In churches and monasteries the members of the nobility, who have often made substantial donations, sit in preferential places (as do their burial places). Their second sons (of both sexes) enter to fill the principal positions, covered by substantial dowries. The testamentary mandates oblige them to perform most of the masses for their eternal salvation. The lands of the Church themselves are of mortmain, that is to say, they are linked to that end and could not be sold until they became national goods in the confiscation. Even the non-privileged who reached a comfortable economic position found it more interesting than the investment of capital, to imitate these strategies of nobiliary origin (what has been called the "betrayal of the bourgeoisie").[27]

The peasants who were part of the ecclesiastical manors did not enjoy economic or legal conditions more lenient than those of a lay manor. In addition, all -in manor and in royalty- were obliged to pay religious taxes (tithes and first fruits), and in an extensive area of Galicia, Leon and Castile, they also paid the Voto de Santiago, which included the Patronage of Spain and its annual recognition by the king or his representative. The ecclesiastical jurisdiction implied, besides the exemption of taxes to all the participants of it, a privative jurisdiction that included the sacredness of the churches (to which any criminal could take refuge, being impossible for the civil justice to arrest him inside them).

A primate see (Toledo) was designated, whose primacy was disputed by Tarragona and Braga, and a network of archdioceses and dioceses that in practice gave the bishops, supported by the canons of the cathedral chapter, enormous authority. The collegiate churches and major churches of the important localities reproduced this collegiate institution. The local archpriestships and parishes closed the institutional base of the network of the secular clergy, very dense in the north of Spain and very dispersed in the south, with areas in Andalusia, La Mancha, Extremadura and Murcia where pastoral care was very deficient. Simultaneously, there was an abundance of unedifying figures such as the beneficiary who accumulated the incomes of various benefices, the chaplains who sang mass with few or no assistants (apart from the altar boy) in the noble palaces, the tonsured clergy who did not exercise any curate or those who received minor orders for the sole purpose of acquiring ecclesiastical privileges. The clerics regular were also similarly implanted throughout the territory, but subdivided into a large number of religious orders of various types, with monasteries (mostly in rural areas) and urban convents (dangerously taxing the local economy, as the municipalities complained, frequently requesting the limitation of new foundations).[28]

The proverbial relaxation of customs and poor formation of the late medieval clergy were the object of energetic reform programs: such as the Synod of Aguilafuente convoked by the Bishop of Segovia Juan Arias Dávila in 1472 (which gave rise to the first book printed in Spain, the Synodal of Aguilafuente), or the more general Council of Aranda convoked by Archbishop Carrillo in 1473; which did not prevent his successor in the see of Toledo, Cardinal Mendoza, known as the third king of Spain, from legitimizing his sons (the "beautiful little sins of the cardinal", according to Isabella the Catholic); or that the succession of the seat of Compostela fell first to the nephew of the previous archbishop and then to his son, linking three Alonsos de Fonseca who must be distinguished with ordinal numbers. This would be the most scandalous case, so that there were those who mocked insinuating that it had been instituted as a Majorat, perhaps inheritable by females. To avoid canonical inconveniences, a brief interregnum of a nephew of the Valencian pope of Borgia (Alexander VI) was inserted. The same thing also happened in the Archidiocese of Burgos with Pablo de Santa Maria and his son Alfonso de Cartagena, although in this case the scandal could not include any reproach to his sexual morals, since the son had had him as a Jewish rabbi before being baptized (no doubt sincerely, but coinciding with the terrible pogroms of 1390).[29] The role of Cardinal Cisneros in the transition from the 15th to the 16th century was decisive for the Spanish Church to become a disciplined mechanism, little accessible to the innovations of the Lutheran reformation, although it did suffer the heartbreaking debate around Erasmism, which had much to do with the resistance to modernization in the religious orders.[30] During the 16th century, a reformist movement of a mystical nature took place, in which Teresa of Jesus and John of the Cross were involved with no little confrontation; and, with a European perspective, the founding of the Society of Jesus by Ignatius of Loyola (all three were later canonized).

Two institutions directly linked to the Church were of great importance: the Military Orders (such as the international Order of Malta and the private Orders of Aragon (Montesa), Castile (Santiago), Alcántara and Calatrava) and the Universities (among which those that came to be known as the major ones: Salamanca, Valladolid and Alcalá, as opposed to the rest of the convents and schools-universities, which came to be known as minor[31] whose social function was much more important than the educational, while the scientific function was practically absent, beyond Law and Theology. Of great importance was the so-called School of Salamanca, which from a neo-scholastic and neo-Aristotelian position can be considered the main builder of the dominant ideology in Habsburg Spain. The life of the Universities was dominated by the confrontations between the different residential colleges, linked to different religious orders, especially Franciscans, Dominicans and Jesuits (such as those that led to the imprisonment of Fray Luis de León, an Augustinian). In the 18th century, within a shameful intellectual decadence that allowed eccentricities such as those of Piscator Diego de Torres Villarroel from Salamanca, the main confrontation took place between the groups known as golillas and manteístas, with derivations to the later political careers of the university students. The attempts at reform produced by the Enlightenment critics (Jovellanos, Meléndez Valdés) did not have any effect. When Ferdinand VII closed universities (at the same time that he opened Pedro Romero's Bullfighting School) their state was definitely catastrophic. The confiscation and the creation of the Central University in Madrid marked the beginning of a university renovation in the middle of the 19th century.

In secondary education, the creation of the Reales Estudios de San Isidro, Colegio Imperial or Seminario de Nobles de Madrid by the jesuits, as a mechanism for recruiting the elites, and the involvement of the Piarists in education were significant from the 17th century onwards. The former earned them many enemies, both among the other religious orders and among the enlightened, as was demonstrated on the occasion of the Esquilache riots (1766). There were also secular teaching institutions, linked to the town councils and entrusted to Latin teachers (some of them notable, such as the Estudio de la Villa de Madrid run by Juan López de Hoyos, where Miguel de Cervantes attended), but by no means generalized. State regulation of primary and secondary education had to wait for the Moyano Law, developed in the second half of the 19th century, although insufficient efforts were made to generalize schooling until the Second Spanish Republic, which sought to restrict the influence of the religious, triumphant again with the subsequent National Catholicism.

As for scientific institutions, apart from the classic organization of the medical profession in the Faculties of Medicine, the Protomedicato was established in the time of Charles V, although it did not become a centralized institution, maintaining local colleges such as the Colegio de San Cosme y San Damián in Pamplona (which did not even have jurisdiction over the whole of Navarre). The organizational needs of the overseas Empire led to the organization in the 16th century of state-sponsored training institutions linked to mining and metallurgy (Almadén) and, above all, to armaments and navigation through the commercial monopoly of the Universidad de Mareantes and the Casa de Contratación, which established the positions of chief pilot and chief cosmographer, a Chair of Navigation and Cosmography from 1552, and later a ship measurer and a Chair of Artillery, fortifications and squadrons.[32] From the 18th century onwards, the French model was imitated with the creation of the Reales Academias. At the end of the Ancien Régime, the Real Colegio de Artillería of Segovia and the network of Sociedades Económicas de Amigos del País appeared.

Dissidence in religious matters was the responsibility of a peculiar institution: the Spanish Inquisition, possibly the only one common to all of Spain, apart from the crown, and which, not having jurisdiction in the European kingdoms (the attempts to suffocate Protestantism in Flanders through its implantation were one of the causes of the success of its revolt) can really be considered as a shaping of the national personality, an extreme on which the anti-Spanish propaganda known as the Black Legend insisted. Its territorial implantation, with courts in strategically chosen cities and above all with a network of informants (familiares) was extraordinarily effective. Its political role sometimes escaped from the usual subjection to the civil power that used to instrumentalize it and even put the latter in trouble (trials of Bishop Carranza, in the 16th century, and of Macanaz[33] and Olavide, in the 18th century).

The role of the Inquisition and the limpieza de sangre statutes in shaping the mindset of the Old Christian was the closest thing that could be reached to the formation of a national identity in Spain in the first centuries of the Modern Age.

See also

editNotes and references

edit- ^ The author of the second was Cardinal Francisco de Mendoza y Bovadilla, written in 1560 as a memorial to King Philip II, where he questioned the cleanliness of blood of the Spanish nobility. The Libro verde de Aragón, from the first half of the 16th century, was a similar manuscript by a counselor of the Aragonese Inquisition, which was widely disseminated.

- ^ Amelang, James S. (1 December 1988). "Tantas personas como estados: Por una antropologia politica de la historia europea. Bartolome Clavero". The Journal of Modern History. 60 (4): 734–735. doi:10.1086/600444. ISSN 0022-2801.

- ^ Baquer, Lorenzo Martín-retortillo (1 January 2004). "Los derechos fundamentales y la Constitución a los veinticinco años". FORO. Revista de Ciencias Jurídicas y Sociales, Nueva Época (in Spanish): 33–58. ISSN 2255-5285.

- ^ SL, DiCom Medios. "Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa Online". www.enciclopedia-aragonesa.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ In the Crown of Castile, after other localities won and lost it, a list of seventeen was established: León, Zamora, Toro, Salamanca, Burgos, Valladolid, Soria, Ávila, Segovia, Madrid, Guadalajara, Toledo, Cuenca, Córdoba, Jaén, Seville and Murcia, to which Granada was added after its conquest. They were those that had been capitals of kingdoms, in addition to some localities that for one reason or another achieved and maintained that privilege.

- ^ Gallego, Miguel Artola (1982). La Hacienda del Antiguo Régimen (in Spanish). Alianza. p. 18. ISBN 978-84-206-8042-2.

- ^ Carande, Ramón (1990). Carlos V y sus banqueros (in Spanish). Crítica. ISBN 978-84-7423-457-2.

- ^ Concept coined by Earl J. Hamilton in The American Treasury and the Price Revolution.

- ^ Madrazo, Santos (1969). Las dos Españas: burguesia y nobleza, los origenes del precapitalismo español (in Spanish). Zero: Distribuidor exclusivo:ZYX, Madrid.

- ^ Roca, Ángel Luis Alfaro (1990). "Fuentes para el estudio del consumo y del comercio alimentario en Madrid en el Antiguo Régimen". Primeras Jornadas sobre fuentes documentales para la historia de Madrid (in Spanish). Dirección General de Patrimonio Cultural: 279–288. ISBN 978-84-451-0173-5 – via Dialnet.

- ^ Website of the Museo de las Ferias, in Medina del Campo, with documentation on its history and that of the textile and wool trade.

- ^ Pablo, Ángel Ruiz y (1994). Historia de la Real Junta Particular de Comercio de Barcelona (1758 a 1847) (in Spanish). Editorial Alta Fulla. ISBN 978-84-7900-059-2.

- ^ Madrazo, Santos (1984). El sistema de transportes en España : 1750 – 1850. Colección de Ciencias, Humanidades e Ingeniería (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Colegio de Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales y Puertos. ISBN 978-84-7506-113-9.

- ^ Clavero, Bartolomé (1974). Mayorazgo: propiedad feudal en Castilla, 1369–1836 (in Spanish). Siglo Veintiuno Editores. ISBN 978-84-323-0128-5.

- ^ The title of one of the key works of arbitrism is Suma de tratos y contratos, by Tomás de Mercado (1569).

- ^ Aparisi, Teresa Canet (2006). "Las Audiencias reales en la Corona de Aragón: de la unidad medieval al pluralismo moderno". Estudis: Revista de historia moderna (in Spanish) (32): 133–174. ISSN 0210-9093.

- ^ "Los manuales, tratados y cursos de Historia del Derecho español". BYBLOS Revista de Historiografía Histórico-Jurídica (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Número monográfico sobre Notarios y juristas de la Corona de Aragón" (PDF). Revista de Estudios Histórico-Jurídicos de la Corona de Aragón. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Parker, Geoffrey (14 October 2004). The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567–1659: The Logistics of Spanish Victory and Defeat in the Low Countries' Wars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54392-7.

- ^ Marín, José Antonio Gómez (1972). Bandolerísmo, santidad y otros temas españoles (in Spanish). M. Castellote.

- ^ "Historia de la PG-ME". Mossos d'Esquadra (in European Spanish). Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Vicente, José Antonio Armillas (2002). Guerra y milicia en la España del X Conde de Aranda : actas IV Congreso de Historia Militar (in Spanish). Departamento de Cultura y Turismo. ISBN 978-84-7753-962-9.

- ^ Villa, Fernando Puell de la (1995). "La ordenanza del reemplazo anual de 1770". Hispania: Revista española de historia (in Spanish). 55 (189): 205–228. ISSN 0018-2141.

- ^ Suárez Fernández, Luis (2008). "La doctrina del máximo religioso". Página Oficial de la Comisión para la Causa de Canonización de la Reina Isabel La Católica. Archived from the original on 16 March 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Flem, Jean-Paul Le; Pérez, Joseph; Pelorson, Jean-Marc (1982). Historia de España: la frustración de un imperio. (1476–1714). Tomo V (in Spanish). Editorial Labor. ISBN 978-84-335-9431-0.

- ^ Elliott, J. H. (25 July 2002). Imperial Spain 1469–1716. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-192557-8.

- ^ "Las clases populares en la Sevilla del siglo XVI". Alma Mater Hispalense. Archived from the original on 2 June 2007. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Church, Politics, and Society in Spain, 1750–1874 — William J. Callahan". www.hup.harvard.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ ""El Hijo del Obispo"". Leyendas de las Tierras Altas de Galicia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Bataillon, Marcel (1950). Erasmo y España: estudios sobre la historia espiritual del siglo XVI (in Spanish). Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- ^ Escatín Sánchez, Eduardo (2003). "Universidades mayores y menores: Una polémica en la Cataluña del siglo XVII". Revista Pedrables (in Spanish). 23: 187–202.

- ^ Artola, Miguel (1988). Enciclopedia de la Historia de España (in Spanish). Vol. 5: Diccionario Temático. Spain: Alianza. ISBN 8420652407.

- ^ Gaite, Carmen Martín (15 December 2014). El proceso de Macanaz: Historia de un empapelamiento (in Spanish). Siruela. ISBN 978-84-16280-17-9.

Bibliography

edit- Anes, Gonzalo (1975), "Historia de España", The Journal of Economic History (in Spanish), 5: El Antiguo Régimen: Los Borbones (4), Alfaguara: 931–933, doi:10.1017/S0022050700098053, S2CID 154586629

- Aróstegui, Julio (1982), Historia de España (in Spanish), vol. 9: Crisis del antiguo régimen: de Carlos IV a Isabel II, Información y Revistas

- Artola, Miguel (1988), Enciclopedia de Historia de España (in Spanish), Alianza, ISBN 9788420652948

- Artola, Miguel (1982), "La Hacienda del Antiguo Régimen", Revista de Historia Economica - Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History (in Spanish), 2 (1), Alianza: 196–198, doi:10.1017/S0212610900012982, S2CID 154593345

- Artola, Miguel (1978), Antiguo régimen y revolución liberal (in Spanish), Ariel

- Ortiz Dominguez, Antonio (1985), Instituciones y sociedad en la España de los Austrias (in Spanish), Ariel, ISBN 9788434465480

- Ortiz Dominguez, Antonio (1981), Historia de España (in Spanish), vol. 6: La Forja del imperio: Carlos V y Felipe II., Historia 16, ISBN 9788434465480

- Ortiz Dominguez, Antonio (1981), Historia de España (in Spanish), vol. 7: Esplendor y decadencia: de Felipe III a Carlos II, Historia 16

- Ortiz Dominguez, Antonio (1981), Historia de España (in Spanish), vol. 8: El reformismo borbónico: la España del XVIII, Historia 16

- Ortiz Dominguez, Antonio (1976), Sociedad y estado en el siglo XVIII español (in Spanish), Ariel, ISBN 9788434465091

- Ortiz Dominguez, Antonio (1988), Historia de España: El Antiguo Régimen: Los Reyes Católicos y los Austrias (in Spanish), Alianza

- García de Valdeavellano, Luis (1998), Curso de historia de las instituciones españolas: de los orígenes al final de la edad media (in Spanish), Alianza, ISBN 9788420681757

- Avilés Fernández, Miguel; Espadas Burgos, Manuel (1987), Gran historia universal (in Spanish), Nájera, ISBN 9788476620410

- Fernández de Pinedo, Emiliano; Gil Novales, Alberto; Dérozier, Albert (1980), Centralismo, ilustración y agonía del Antiguo Régimen (1715-1833) (in Spanish), Labor, ISBN 9788433594204

- Le Flem, Jean Paul (1982), La Frustración de un imperio (1476-1714) (in Spanish), Labor, ISBN 9788433594310

- Salrach i Marés, Josep Maria; Espalader, Anton (1996), Historia de España (in Spanish), vol. 12: La corona de Aragón, plenitud y crisis: de Pedro el Grande a Juan II, 1276–1479, Historia 16, ISBN 9788476620410

- Valdeón Baruque, Julio; Salvador Miguel, Nicasio (1995), Castilla se abre al Atlántico. De Alfonso X a los Reyes Católicos (in Spanish), Temas de Hoy, ISBN 9788476792889

- Valdeón Baruque, Julio (1981), Historia de España (in Spanish), vol. 5: La Baja edad media: crisis y renovación en los siglos XIV-XV, Historia 16