Andrew Michael Sullivan (born 10 August 1963) is a British-American political commentator. Sullivan is a former editor of The New Republic, and the author or editor of six books. He started a political blog, The Daily Dish, in 2000, and eventually moved his blog to platforms, including Time, The Atlantic, The Daily Beast, and finally an independent subscription-based format. He retired from blogging in 2015.[1] From 2016 to 2020, Sullivan was a writer-at-large at New York.[2][3] He launched his newsletter The Weekly Dish in July 2020.[4]

Andrew Sullivan | |

|---|---|

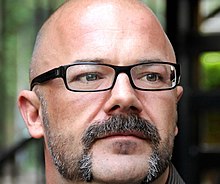

Sullivan in 2006 | |

| Born | Andrew Michael Sullivan 10 August 1963 South Godstone, Surrey, England |

| Citizenship | |

| Education | Magdalen College, Oxford (BA) Harvard University (MPA, PhD) |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse |

Aaron Tone

(m. 2007; div. 2023) |

| Website | dish |

Sullivan has said that his conservatism is rooted in his Catholic background and in the ideas of the British political philosopher Michael Oakeshott.[5][6] In 2003, he wrote that he could no longer support the American conservative movement, as he was disaffected with the Republican Party's continued rightward shift toward social conservatism during the George W. Bush era.[7]

Born and raised in Britain, Sullivan has lived in the U.S. since 1984. He is openly gay and a practicing Catholic.[8][9]

Early life and education

editSullivan was born in South Godstone, Surrey, England, into a Catholic family of Irish descent,[10] and was brought up in the nearby town of East Grinstead, West Sussex. He was educated at a Catholic primary school and at Reigate Grammar School,[11][12] where his classmates included Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Keir Starmer and Conservative member of the House of Lords Andrew Cooper.[13] He won a scholarship in 1981 to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he was awarded a first-class Bachelor of Arts in modern history and modern languages.[14] He founded the Pooh Stick Society at Oxford and in his second year was elected president of the Oxford Union for Trinity term 1983.[11]

After writing briefly for a newspaper, Sullivan won a scholarship in 1984 to Harvard University,[11] where he earned a Master in Public Administration in 1986 from the John F. Kennedy School of Government[15] and a Ph.D. in government in 1990. His dissertation was titled Intimations Pursued: The Voice of Practice in the Conversation of Michael Oakeshott.[16]

Career

editSullivan first wrote for The Daily Telegraph on American politics.[11] In 1986, he went to work for The New Republic magazine initially on a summer internship; among the most significant articles he wrote were "Gay Life Gay Death", an essay on the AIDS crisis, and "Sleeping with the Enemy", in which he attacked the practice of "outing", both of which earned him recognition in the gay community.[11] He was appointed the editor of The New Republic in October 1991, a position he held until 1996.[14] In that position, he expanded the magazine from its traditional roots in political coverage to cultural issues and the politics surrounding them. During this time, the magazine generated several high-profile controversies.[17]

While completing graduate work at Harvard in 1988, Sullivan published an attack in Spy magazine on Rhodes Scholars, "All Rhodes Lead Nowhere in Particular", which dismissed them as "hustling apple-polisher[s]"; "high-profile losers"; "the very best of the second-rate"; and "misfits by the very virtue of their bland, eugenic perfection." "[T]he sad truth is that as a rule," Sullivan wrote, "Rhodies possess none of the charms of the aristocracy and all of the debilities: fecklessness, excessive concern that peasants be aware of their achievement, and a certain hemophilia of character."[18] Author Thomas Schaeper notes that "[i]ronically, Sullivan had first gone to the United States on a Harkness Fellowship, one of many scholarships spawned in emulation of the Rhodes program."[18]

In 1994, Sullivan published excerpts on race and intelligence from Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray's controversial The Bell Curve, which argued that some of the measured difference in IQ scores among racially defined groups was a result of genetic inheritance. Almost the entire editorial staff of the magazine threatened to resign if material that they considered racist was published.[17] To appease them, Sullivan included lengthy rebuttals from 19 writers and contributors. He has continued to speak approvingly of the research and arguments presented in The Bell Curve, writing, "The book ... still holds up as one of the most insightful and careful of the last decade. The fact of human inequality and the subtle and complex differences between various manifestations of being human—gay, straight, male, female, black, Asian—is a subject worth exploring, period."[19] According to Sullivan, this incident was a turning point in his relationship with the magazine's staff and management, which he conceded was already bad because he "was a lousy manager of people."[17] He left the magazine in 1996.

Sullivan began writing for The New York Times Magazine in 1998, but editor Adam Moss fired him in 2002. Jack Shafer wrote in Slate magazine that he had asked Moss in an email to explain this decision, but that his emails went unanswered, adding that Sullivan was not fully forthcoming on the subject. Sullivan wrote on his blog that the decision had been made by Times executive editor Howell Raines, who found Sullivan's presence "uncomfortable", but defended Raines's right to fire him. Sullivan suggested that Raines did so in response to Sullivan's criticism of the Times on his blog, and said he had expected that his criticisms would anger Raines.[20]

Sullivan has also worked as a columnist for The Sunday Times of London.[21]

Ross Douthat and Tyler Cowen have suggested that Sullivan is the most influential political writer of his generation, particularly because of his very early and strident support for same-sex marriage, his early political blog, his support of the Iraq War, and his support of Barack Obama's presidential candidacy.[22]

After the cessation of his long-running blog, The Dish, in 2015,[23] Sullivan wrote regularly for New York during the 2016 presidential election,[24] and in 2017 began writing a weekly column, "Interesting Times", for the magazine.[25]

On July 19, 2020, after the unexplained absence of his column for June 5,[26] Sullivan announced that he would no longer write for New York and would be reviving The Dish as a newsletter, The Weekly Dish, hosted by Substack.[4][27]

Politics

editSullivan describes himself as a conservative and is the author of The Conservative Soul. He has supported a number of traditional libertarian positions, favouring limited government and opposing social interventionist measures such as affirmative action.[28] But on many controversial public issues, including same-sex marriage, social security, progressive taxation, anti-discrimination laws, the Affordable Care Act, the U.S. government's use of torture, and capital punishment, he has taken positions not typically shared by conservatives in the United States.[28] In 2012, Sullivan said, "the catastrophe of the Bush–Cheney years ... all but exploded the logic of neoconservatism and its domestic partner-in-crime, supply-side economics."[29]

One of the most important intellectual and political influences on Sullivan is Michael Oakeshott.[6] Sullivan describes Oakeshott's thought as "an anti-ideology, a nonprogramme, a way of looking at the world whose most perfect expression might be called inactivism."[17] He argues "that Oakeshott requires us to systematically discard programmes and ideologies and view each new situation sui generis. Change should only ever be incremental and evolutionary. Oakeshott viewed society as resembling language: it is learned gradually and without us really realising it, and it evolves unconsciously, and for ever."[17] In 1984, he wrote that Oakeshott offered "a conservatism which ends by affirming a radical liberalism."[17] This "anti-ideology" is perhaps the source of accusations that Sullivan "flip-flops" or changes his opinions to suit the whims of the moment. He has written, "A true conservative—who is, above all, an anti-ideologue—will often be attacked for alleged inconsistency, for changing positions, for promising change but not a radical break with the past, for pursuing two objectives—like liberty and authority, or change and continuity—that seem to all ideologues as completely contradictory."[30]

As a youth, Sullivan was a fervent supporter of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. He says of that time, "What really made me a right-winger was seeing the left use the state to impose egalitarianism—on my school",[17] after the Labour government in Britain tried to merge his admissions-selective school with the local comprehensive school. At Oxford, he became friends with prominent conservatives William Hague and Niall Ferguson and became involved with Conservative Party politics.[17]

From 1980 through 2000, Sullivan supported Republican presidential candidates in the U.S.,[17] with the exception of the 1992 election, when he supported Bill Clinton.[31] In 2004, he was angered by George W. Bush's support of the Federal Marriage Amendment designed to enshrine in the Constitution marriage as a union between a man and a woman, as well as what he saw as the Bush administration's incompetent management of the Iraq War,[32] and supported Democratic nominee John Kerry.

Sullivan endorsed Senator Barack Obama for the Democratic nomination in the 2008 United States presidential election, and Representative Ron Paul for the Republican nomination. After John McCain clinched the Republican primary and named Sarah Palin as his running mate, Sullivan began to espouse a birther-like conspiracy theory involving Palin and her young son Trig.[33] Sullivan devoted a significant amount of space in The Atlantic to questioning whether Palin is Trig's biological mother. He and others who held this belief, dubbed "Trig Truthers", demanded Palin produce a birth certificate or other piece of medical evidence to prove Trig is indeed Palin's biological son.[34]

Sullivan eventually endorsed Obama for president, largely because he believed Obama would restore "the rule of law and Constitutional balance"; he also argued that Obama represented a more realistic prospect for "bringing America back to fiscal reason" and expressed hope that Obama could "get us past the culture war."[35] Sullivan continued to maintain that Obama was the best choice for president from a conservative point of view. During the 2012 election campaign, he wrote, "Against a radical right, reckless, populist insurgency, Obama is the conservative option, dealing with emergent problems with pragmatic calm and modest innovation. He seeks as a good Oakeshottian would to reform the country's policies in order to regain the country's past virtues. What could possibly be more conservative than that?"[36] Sullivan has declared support for Arnold Schwarzenegger[37] and other like-minded Republicans.[38][39] He argues that the Republican Party, and much of the conservative movement in the U.S., has largely abandoned its earlier scepticism and moderation in favour of a more fundamentalist certainty, both in religious and political terms.[40] He has said this is the primary source of his alienation from the modern Republican Party.[41]

In 2009, Forbes ranked Sullivan 19th on a list of "The 25 Most Influential Liberals in the U.S. Media".[42] Sullivan rejected the "liberal" label and set out his grounds in a published article in response.[43]

In 2018, after Sarah Jeong, an editorial board member of The New York Times, received widespread criticism for her old anti-white tweets, Sullivan accused her of being racist and calling white people "subhuman". He also accused Jeong of spreading eliminationism,[44][45] the belief that political opponents are a societal cancer who should be separated, censored, or exterminated.[46]

LGBT issues

editHIV

editIn 1996, discussing HIV, he argued in the New York Times Magazine that "this plague is over" insofar as "it no longer signifies death. It merely signifies illness."[47] This led to "a trend of white male journalists proclaiming that AIDS is over", according to Sarah Schulman.[48]

Gay issues

editSullivan, like Marshall Kirk, Hunter Madsen, and Bruce Bawer, has been described by Urvashi Vaid as a proponent of "legitimation", seeing the objective of the gay rights movement as "mainstreaming gay and lesbian people" rather than "radical social change".[49] Sullivan wrote the first major article in the U.S. advocating for gay people to be given the right to marry,[17] published in The New Republic in 1989.[50] According to one columnist for Intelligent Life, many on "the gay left," aiming to alter social codes of sexuality for everyone, were chagrined at Sullivan's endorsement of the "assimilation" of gay people into "straight culture."[17] In the wake of the United States Supreme Court rulings on same-sex marriage in 2013 (Hollingsworth v. Perry and United States v. Windsor), The New York Times op-ed columnist Ross Douthat suggested that Sullivan might be the most influential political writer of his generation, writing: "No intellectual that I can think of, writing on a fraught and controversial topic, has seen their once-crankish, outlandish-seeming idea become the conventional wisdom so quickly, and be instantiated so rapidly in law and custom."[22]

As of 2007, Sullivan opposed hate crime laws, arguing that they undermine freedom of speech and equal protection.[51]

In 2014, Sullivan opposed calls to remove Brendan Eich as CEO of Mozilla for donating to the campaign for Proposition 8, which made same-sex marriage illegal in California.[52][53][54] In 2015, he claimed that "gay equality" had been achieved in the U.S. by the persuasive arguments of "old-fashioned liberalism" rather than the activism of "identity politics leftism."[55]

Transgender issues

editIn 2007, Sullivan said he was "no big supporter" of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act, arguing that it would "not make much of a difference." He said the "gay rights establishment" was making a tactical error by insisting on protections for gender identity, as he believed it would be easier to pass the bill without transgender people.[56]

In a September 2019 Intelligencer column, Sullivan expressed concern that gender-nonconforming children (especially those who are likely one day to come out as gay) might be encouraged to believe that they are transgender when they are not.[57] In November 2019, Sullivan wrote another Intelligencer column on young women who, in their teens, had begun to transition to live as men but later detransitioned. In that article, he discussed the controversy over a 2018 journal article by Lisa Littman that proposed a socially mediated subtype of gender dysphoria that Littman had termed "rapid onset gender dysphoria".[58] In April 2021, he said it should be illegal for doctors to initiate cross-sex hormones for children under 16 or sex reassignment surgery for children under 18.[59]

Recognitions

editIn 1996, Sullivan's book Virtually Normal: An Argument about Homosexuality won the Mencken Award for Best Book, presented by the Free Press Association.[60] In 2006, Sullivan was named an LGBT History Month icon.[61]

Foreign policy

editIraq war, war on terror

editSullivan supported the United States' 2003 invasion of Iraq and was initially hawkish in the war on terror, arguing that weakness would embolden terrorists. He was "one of the most militant"[17] supporters of the Bush administration's counter-terrorism strategy immediately following the September 11 attacks in 2001; in an essay for The Sunday Times, he wrote, "The middle part of the country—the great red zone that voted for Bush—is clearly ready for war. The decadent Left in its enclaves on the coasts is not dead—and may well mount what amounts to a fifth column."[62] Eric Alterman wrote in 2002 that Sullivan had "set himself up as a one-man House Un-American Activities Committee" running an "inquisition" to unmask "anti-war Democrats", "basing his argument less on the words these politicians speak than on the thoughts he knows them to be holding in secret".[63]

Later, Sullivan criticised the Bush administration for its prosecution of the war, especially regarding the numbers of troops, protection of munitions, and treatment of prisoners, including the use of torture against detainees in U.S. custody.[64] He argued that enemy combatants in the war on terror should not have been given status as prisoners of war because "terrorists are not soldiers",[65] but he believed that the U.S. government was required to abide by the rules of war—in particular, Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions—when dealing with such detainees.[66] In retrospect, Sullivan said that the torture and abuse of prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq had jolted him back to "sanity".[17] Of his early support for the invasion of Iraq, he said, "I was terribly wrong. In the shock and trauma of 9/11, I forgot the principles of scepticism and doubt towards utopian schemes that I had learned."[17]

On the 27 October 2006 episode of Real Time with Bill Maher, Sullivan described conservatives and Republicans who refused to admit they had been wrong to support the Iraq War as "cowards". On 26 February 2008, he wrote on his blog: "After 9/11, I was clearly blinded by fear of al Qaeda and deluded by the overwhelming military superiority of the US and the ease of democratic transitions in Eastern Europe into thinking we could simply fight our way to victory against Islamist terror. I wasn't alone. But I was surely wrong."[67] His reversal on Iraq and increasing attacks on the Bush administration caused a severe backlash from many hawkish conservatives, who accused him of not being a "real" conservative.[17]

Sullivan authored an opinion piece, "Dear President Bush," that was featured as the cover article of the October 2009 edition of The Atlantic.[68] In it, he called on Bush to take personal responsibility for the incidents and practices of torture that occurred during his administration as part of the war on terror.

Israel

editSullivan has said that he has "always been a Zionist",[69] but his views of Israel have become more critical over time. In February 2009, he wrote that he could no longer take the neoconservative position on Israel seriously.[70]

In January 2010, Sullivan blogged that he was "moving toward" the idea of "a direct American military imposition" of a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with NATO troops enforcing "the borders of the new states of Palestine and Israel". He wrote, "I too am sick of the Israelis. [...] I'm sick of having a great power like the US being dictated to."[71] His post was criticised by Noah Pollak of Commentary, who called it "crazy", "heady stuff" based on "hubris".[72]

In February 2010, Leon Wieseltier suggested in The New Republic that Sullivan, a former friend and colleague, had a "venomous hostility toward Israel and Jews" and was "either a bigot, or just moronically insensitive" toward the Jewish people.[73] Sullivan rejected the accusation and was defended by some writers, while others at least partly supported Wieseltier.[74]

In March 2019, Sullivan wrote in New York magazine that while he strongly supported the right of a Jewish state to exist, he felt that U.S. Representative Ilhan Omar's comments about the influence of the pro-Israel lobby were largely correct. He said, "it is simply a fact that the Israel lobby uses money, passion, and persuasion to warp this country's foreign policy in favor of another country—out of all proportion to what Israel can do for the US."[75]

Iran

editSullivan devoted a significant amount of blog space to the allegations of fraud and related protests after the 2009 Iranian presidential election. Francis Wilkinson of The Week said that Sullivan's "coverage—and that journalism term takes on new meaning here—of the uprising in Iran was nothing short of extraordinary. 'Revolutionary' might be a better word."[76]

Sullivan was inspired by the Iranian people's reactions to the election results and used his blog as a hub of information. Because of the media blackout in Iran, Iranian Twitter accounts were a major source of information. Sullivan frequently quoted and linked to Nico Pitney of The Huffington Post.[77]

Immigration

editWriting for New York magazine, Sullivan expressed concern that high levels of immigration to the U.S. could drive "white anxiety" by making white Americans "increasingly troubled by the pace of change" since they were never asked whether they wanted such a demographic shift.[78] Sullivan has advocated for tighter immigration controls on asylum and overall lower levels of immigration. He has criticized Democrats for what he perceived as their unwillingness to implement such controls.[79]

Race

editAs editor at The New Republic, Sullivan published excerpts from the 1994 book The Bell Curve, by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray. The book, which contains a chapter about IQ in society and public policy, argues that there are innate differences in intelligence among racial groups.[80] This view of an innate connection between race and intelligence is rejected by the majority of scientists.[81][82][83][84][85]

In a 2015 article in The New Republic, "The New Republic's Legacy on Race", Jeet Heer called Sullivan's decision an example of the magazine's "myopia on racial issues".[86] The importance of Sullivan to the popularization of The Bell Curve and race science was noted by Matthew Yglesias, who called Sullivan "the punditocracy's original champion of Murray's thinking on genetics".[87] Similarly, Gavin Evans wrote in The Guardian that Sullivan "was one of the loudest cheerleaders for The Bell Curve in 1994" and that he "returned to the fray in 2011, using his popular blog, The Dish, to promote the view that population groups had different innate potentials when it came to intelligence."[80]

Blogging

editIn late 2000, Sullivan began his blog, The Daily Dish. The core principle of the blog has been the style of conservatism he views as traditional. This includes fiscal conservatism, limited government, and classic libertarianism on social issues. Sullivan opposes government involvement with respect to sexual and consensual matters between adults, such as the use of marijuana and prostitution. He believes recognition of same-sex marriage is a civil-rights issue but expressed willingness to promote it on a state-by-state legislative federalism basis, rather than trying to judicially impose the change.[88] Most of Sullivan's disputes with other conservatives have been over social issues and the handling of postwar Iraq.

Sullivan gave out yearly "awards" for various public statements, parodying those of the people the awards were named after. Throughout the year, nominees were mentioned in various blog posts. The readers of his blog chose winners at the end of each year.[89]

- The Hugh Hewitt Award, introduced in June 2008 and named after a man Sullivan described as an "absurd partisan fanatic", was for the most egregious attempts to label Barack Obama as un-American, alien, treasonous, and far out of the mainstream of American life and politics.

- The John Derbyshire Award was for egregious and outlandish comments on gays, women, and minorities.

- The Paul Begala Award was for extreme liberal hyperbole.

- The Michelle Malkin Award was for shrill, hyperbolic, divisive, and intemperate right-wing rhetoric. (Ann Coulter was ineligible for this award so that, in Sullivan's words, "other people will have a chance.")

- The Michael Moore Award was for divisive, bitter, and intemperate left-wing rhetoric.

- The Matthew Yglesias Award was for writers, politicians, columnists, or pundits who criticised their own side of the political spectrum, made enemies among political allies, and generally risked something for the sake of saying what they believed.

- The "Poseur Alert" was awarded for passages of prose that stood out for pretension, vanity, and bad writing designed to look profound.

- The Dick Morris Award (formerly the Von Hoffman Award) was for stunningly wrong cultural, political, and social predictions. Sullivan renamed this award in September 2012, saying that Von Hoffman was "someone who in many ways got the future right—at least righter than I did."

In February 2007, Sullivan moved his blog from Time to The Atlantic Monthly, where he had accepted an editorial post. His presence was estimated to have contributed as much as 30% of the subsequent traffic increase for The Atlantic's website.[90]

In 2009, The Daily Dish won the 2008 Weblog Award for Best Blog.[91]

Sullivan left The Atlantic to begin blogging at The Daily Beast in April 2011.[92] In 2013, he announced that he was leaving The Daily Beast to launch The Dish as a stand-alone website, charging subscribers $20 a year.[93][94]

In a note posted on The Dish on 28 January 2015, Sullivan announced his decision to retire from blogging.[95][96] He posted his final blog entry on 6 February 2015.[97] On 26 June 2015, he posted an additional piece in reaction to Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized same-sex marriage in the United States.[98]

In July 2020, Sullivan announced that The Dish would be revived as a weekly feature, including a column and podcast;[99] he published there and elsewhere a notable obituary of Queen Elizabeth II.[100]

Personal life

editIn 2001, it came to light that Sullivan had posted anonymous online advertisements for unprotected anal sex, preferably with "other HIV-positive men". He was widely criticised in the media for this, with some critics noting that he had condemned Bill Clinton's "incautious behavior", though others wrote in his defence.[101][102][103][104]

In 2003, Sullivan wrote a Salon article identifying himself as a member of the gay "bear community".[105] On 27 August 2007, he married Aaron Tone in Provincetown, Massachusetts.[106][107][108] On May 26, 2023, Sullivan announced on his blog that he and Tone had divorced the previous week.[109]

Sullivan was barred for many years from applying for U.S. citizenship because of his HIV-positive status.[110] Following the statutory and administrative repeals of the HIV immigration ban in 2008 and 2009, respectively, he announced his intention to begin the process of becoming a permanent resident and citizen.[111][112] On The Chris Matthews Show on 16 April 2011, Sullivan confirmed that he had become a permanent resident, showing his green card.[113] On 1 December 2016, Sullivan became a naturalised US citizen.[114]

He has been a daily user of cannabis since 2001.[115]

Religion

editSullivan identifies himself as a faithful Catholic while disagreeing with some aspects of the Catholic Church's doctrine.

He expressed concern about the election of Pope Benedict XVI in a Time magazine article on 24 April 2005, titled "The Vicar of Orthodoxy".[116] He wrote that Benedict was opposed to the modern world and women's rights, and considered gays and lesbians innately disposed to evil. Sullivan has, however, agreed with Benedict's assertion that reason is an integral element of faith.

Sullivan takes a moderate approach to religion, rejecting fundamentalism and describing himself as a "dogged defender of pluralism and secularism." Sullivan was a friend of late journalist and atheist writer Christopher Hitchens,[117][118]and often debated religion with him.[119] Sullivan also defended religious moderates in a series of exchanges with atheist author Sam Harris.

Works

edit- As author

- Virtually Normal: An Argument About Homosexuality (1995). Knopf. ISBN 0-679-42382-6.

- Love Undetectable: Notes on Friendship, Sex and Survival (1998). Knopf. ISBN 0-679-45119-6.

- The Conservative Soul: How We Lost It, How to Get It Back (2006). HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-018877-4.

- Intimations Pursued: The Voice of Practice in the Conversation of Michael Oakeshott (2007). Imprint Academic. ISBN 978-0-907845-28-7

- Out on a Limb: Selected Writing, 1989–2021 (2021). Avid Reader Press. ISBN 978-1501155895

- As editor

- Same-Sex Marriage Pro & Con: A Reader (1997). Vintage. ISBN 0-679-77637-0. First edition

- Same-Sex Marriage Pro & Con: A Reader (2004). Vintage. ISBN 1-4000-7866-0. Second edition

- The View from Your Window: The World as Seen by Readers of One Blog (2009). Blurb.com

References

edit- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (28 January 2015). "Andrew Sullivan Retires From Blogging". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ "Andrew Sullivan Joins New York Magazine As Contributing Editor". New York Press Room. 1 April 2016. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ "Longtime columnist and blogger Andrew Sullivan resigns from New York magazine". CNN Business. 14 July 2020. Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Andrew (17 July 2020). "See You Next Friday: A Farewell Letter". New York. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Allison, Maisie (14 March 2013). "Beyond Fox News". The American Conservative. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Ask Andrew Anything: Oakeshott's Influence". The Daily Beast. 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (1 December 2009). "Leaving the Right". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Oliveira, Philip de (9 July 2017). "Conservative gay writer Andrew Sullivan makes a case for faith". Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "Sullivan's Catholicism | Commonweal Magazine". www.commonwealmagazine.org. 8 February 2015. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Raban, Jonathan (12 April 2007). "Cracks in the House of Rove: The Conservative Soul by Andrew Sullivan". New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Toomey, Christine (1992). "Englishman Aboard". The Sunday Times Magazine. pp. 44–46.

- ^ "Notable Past Pupils". The Old Reigatian Association, Foundation and Alumni Office, Reigate Grammar School. Archived from the original on 24 June 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ Maguire, Patrick (31 March 2020). "Keir Starmer: The sensible radical". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Andrew's Bio". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ Van Auken, Dillon (18 November 2011). "Andrew Sullivan Lectures at IOP". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on 8 August 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ Brooks, David (27 December 2003). "Arguing With Oakeshott". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Hari, Johann (Spring 2009). "Andrew Sullivan: Thinking. Out. Loud". Intelligent Life. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Andrew. "All Rhodes Lead Nowhere in Particular Archived 11 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine", Spy, October 1988, pp. 108–114. Quoted in Schaeper, Thomas J.; Schaeper, Kathleen. The Rhodes Scholarship, Oxford, and the Creation of an American Elite, Berghahn Books, 2010, pp. 281–285. ISBN 978-1845457211

- ^ Metcalf, Stephen (17 October 2005). "The Bell Curve revisited". Slate. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- ^ Shafer, Jack (15 May 2002). "Raines-ing in Andrew Sullivan". Slate. Archived from the original on 19 January 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ Andrew Sullivan (23 June 2013). "Back together: me, Fatboy Slim and the rest of the Upwardly Mobile Gang". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ a b Douthat, Ross (2 July 2013). "The Influence of Andrew Sullivan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (6 February 2015). "The Years of Writing Dangerously". The Dish. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "Most recent Articles By:Andrew Sullivan". Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (17 July 2020). "The Madness of King Donald". New York. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (4 June 2020). "Heads up: my column won't be appearing this week". Twitter. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Recker, Jane (22 December 2020). "Substack Is Attracting Big DC Journos. Who's Making the Leap?". Washingtonian. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ a b Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: ""Conservatism And Its Discontents" T. H. White Lecture with Andrew Sullivan". YouTube. 28 November 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ "Yglesias Award Nominee" Archived 10 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine The Dish 6 July 2012

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (13 November 2013). "The Necessary Contradictions of a Conservative". The Daily Dish. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ Davidson, Telly (14 July 2016). Culture War: How the '90s Made Us Who We Are Today (Whether We Like It or Not). McFarland. p. 42. ISBN 9781476666198. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew. "Why I Am Supporting John Kerry". Free Republic. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Sarah Palin slams Newsweek for giving 'conspiracy kook writer' Andrew Sullivan cover story". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Elliott, Justin (26 April 2011). "Trig Trutherism: A response to Andrew Sullivan". Salon. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "The Daily Dish | By Andrew Sullivan (3 November 2008) – Barack Obama For President". Andrew Sullivan. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (24 August 2012). "America's Tory President". The Daily Dish. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ "Saturday, 11 October 2003". Sullivan Chronicles. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012.

- ^ "The Daily Dish | By Andrew Sullivan". Andrew Sullivan. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ "Ron Paul For The GOP Nomination" Archived 19 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine 14 December 2011, The Daily Beast

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (14 August 2011). "The Christianist Takeover". The Daily Dish. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (16 October 2013). "The Tea Party As A Religion". The Daily Dish. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ Varadarajan, Tunku; Eaves, Elisabeth; Alberts, Hana R. (22 January 2009). "The 25 Most Influential Liberals in the U.S. Media". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2 May 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (24 January 2009). "Forbes' Definition Of "Liberal"". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ Klein, Ezra (8 August 2018). "The problem with Twitter, as shown by the Sarah Jeong fracas". Vox. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "'Goblins,' 'Gooks' and 'Cancel All White Men.' The New York Times Makes a Controversial Hire". Al Bawaba. 5 August 2018. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "When Racism Is Fit to Print". New York. 3 August 2018. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (10 November 1996). "When Plagues End". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ Schulman, Sarah (2021). Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993. New York City: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. xxii. ISBN 978-0-374-71995-1. OCLC 1251803405. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ Vaid, Urvashi (1996). Virtual Equality: The Mainstreaming of Gay & Lesbian Liberation. New York City: Doubleday. p. 37. ISBN 978-1101972342.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (9 November 2012). "Here Comes the Groom". Slate. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ "The Daily Dish | By Andrew Sullivan (3 May 2007) – Hate Crimes and Double Standards". Andrew Sullivan. Archived from the original on 8 March 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ "The Hounding of a Heretic". The Dish. 3 April 2014. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ^ "Andrew Sullivan Blows Colbert's Mind with Defense of Brendan Eich". mediaite.com. 10 April 2014. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ^ "Andrew Sullivan sparks ire of gay community over defense of former Mozilla CEO Brendan Eich". Tech Times. 12 April 2014. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ^ "The Left's Intensifying War on Liberalism " The Dish". The Dish. 27 January 2015. Archived from the original on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ^ "Andrew Sullivan Supports Barney Frank / Queerty". Queerty. 12 October 2007. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (20 September 2019). "Andrew Sullivan: When the Ideologues Come for the Kids". Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (1 November 2019). "Andrew Sullivan: The Hard Questions About Young People and Gender Transitions". Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (9 April 2021). "A Truce Proposal in the Trans Wars". Substack. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "The Mencken Awards: 1982–1996". Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "Andrew Sullivan". LGBTHistoryMonth.com. 20 August 2011. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Noah, Timothy (2 December 2002). "Gore, Sullivan, and "Fifth Column"". Slate. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ^ Alterman, Eric (8 April 2002). "Sullivan's Travails". The Nation. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ "Archives: Daily Dish". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ "The View From Your Window". andrewsullivan.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2005. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "The Reality of War". The Daily Dish. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "McCain's National Greatness Conservatism". The Daily Dish. Andrew Sullivan. 26 February 2008. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Cleland, Elizabeth (1 October 2009). "Dear President Bush". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ A. Sullivan, Mr Netanyahu "Expects" Archived 23 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 20 May 2011.

- ^ Andrew Sullivan,"A False Premise" Archived 29 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Sullivan's Daily Dish, 5 February 2009.

- ^ "Sick". 6 January 2010. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ Pollak, Noah (6 January 2010). "Andrew Sullivan: It's Time to Invade Israel". Commentary. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ Wieseltier, Leon (8 February 2010). "Something Much Darker. Andrew Sullivan has a serious problem". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ "19 Pundits on the Sullivan-Wieseltier Debate". The Atlantic. 11 February 2010. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (8 March 2019). "How Should We Talk About the Israel Lobby's Power?". Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 10 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Wilkinson, Francis. "The future belongs to Andrew Sullivan". The Week. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (22 June 2009). "Is Iran Calming Down?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2 February 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (12 April 2019). "Andrew Sullivan: The Opportunity of White Anxiety". Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (26 October 2018). "Democrats Can't Keep Dodging Immigration as a Real Issue". Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ a b Evans, Gavin (2 March 2018). "The unwelcome revival of 'race science'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Jackson, John P.; Winston, Andrew S. (March 2021). "The Mythical Taboo on Race and Intelligence". Review of General Psychology. 25 (1): 3–26. doi:10.1177/1089268020953622.

[G]eneticists largely reject the conclusions of hereditarian psychology" (p. 5). "Hereditarians thus create an illusion of mainstream research while remaining a minor outlier in psychology (p. 7)

- ^ Bird, Kevin A. (June 2021). "No support for the hereditarian hypothesis of the Black–White achievement gap using polygenic scores and tests for divergent selection". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 175 (2): 465–476. doi:10.1002/ajpa.24216.

- ^ Birney, Ewan; Raff, Jennifer; Rutherford, Adam; Scally, Aylwyn (24 October 2019). "Race, genetics and pseudoscience: an explainer". Ewan's Blog: Bioinformatician at large. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

'Human biodiversity' proponents sometimes assert that alleged differences in the mean value of IQ when measured in different populations – such as the claim that IQ in some sub-Saharan African countries is measurably lower than in European countries – are caused by genetic variation, and thus are inherent. . . . Such tales, and the claims about the genetic basis for population differences, are not scientifically supported. In reality for most traits, including IQ, it is not only unclear that genetic variation explains differences between populations, it is also unlikely.

- ^ Aaron, Panofsky; Dasgupta, Kushan (28 September 2020). "How White nationalists mobilize genetics: From genetic ancestry and human biodiversity to counterscience and metapolitics". American Journal of Biological Anthropology. 175 (2): 387–398. doi:10.1002/ajpa.24150. PMC 9909835. PMID 32986847. S2CID 222163480.

[T]he claims that genetics defines racial groups and makes them different, that IQ and cultural differences among racial groups are caused by genes, and that racial inequalities within and between nations are the inevitable outcome of long evolutionary processes are neither new nor supported by science (either old or new).

- ^ Nisbett, Richard E.; Aronson, Joshua; Blair, Clancy; Dickens, William; Flynn, James; Halpern, Diane F.; Turkheimer, Eric (2012). "Group differences in IQ are best understood as environmental in origin" (PDF). American Psychologist. 67 (6): 503–504. doi:10.1037/a0029772. ISSN 0003-066X. PMID 22963427. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Heer, Jeet (29 January 2015). "The New Republic's Legacy on Race". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Yglesias, Matthew (10 April 2018). "The Bell Curve is about policy. And it's wrong". Vox. Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (24 June 2004). "Give Federalism a Chance". The Stranger. Archived from the original on 4 August 2004. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Andrew Sullivan (16 September 2008). "The Daily Dish Awards". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "A Venerable Magazine Energizes Its Web Site". The New York Times. 21 January 2008. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "The 2008 Weblog Awards". The 2008 Weblog Awards. Archived from the original on 8 August 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Cleland, Elizabeth (1 April 2011). "Home News". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Gillmor, Dan (3 January 2013). "Andrew Sullivan plans to serve Daily Dish by subscription". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Bell, Emily (6 January 2013). "The Daily Dish may feed minds but will Andrew Sullivan taste a profit?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "A Note To My Readers". 28 January 2015. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Andrew Sullivan, blogger extraordinaire, decides that it's time to stop dishing, The Washington Post, 28 January 2015

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (6 February 2015). "The Years of Writing Dangerously". The Daily Dish. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "It Is Accomplished". The Dish. 26 June 2015. Archived from the original on 3 September 2024. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (17 July 2020). "Andrew Sullivan: See You Next Friday". Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 17 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "The genius of a monarchy embedded in a democracy," National Post 19 Sep. 2022.

- ^ "Andrew Sullivan, Overexposed". The Nation. Archived from the original on 17 May 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ "My story was ethical". Salon. 5 June 2001. Archived from the original on 2 September 2003. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ "Salon.com Andrew Sullivan's jihad". Salon. 20 October 2001. Archived from the original on 30 August 2003. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ "Salon.com in defense of Andrew Sullivan". Salon. 2 June 2001. Archived from the original on 30 August 2003. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ "I am bear, hear me roar!". Salon. 1 August 2003. Archived from the original on 28 December 2003. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Argetsinger, Amy; Roberts, Roxanne (26 April 2007). "At Artomatic, a Rocket Ship Blasts Off; That's the Breaks". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Independent Gay Forum – The Poltroon and the Groom". Indegayforum.org. Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (19 August 2007). "My small gay wedding is finally here help". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrews (26 May 2023). "The Resistance Resists...DeSantis". The Weekly Dish. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

Almost two decades after we met, Aaron and I got a divorce last week. It hasn't been easy, and my heart is still somewhat broken, but we are still close, and love and care deeply for each other, and always will, and this was a very amicable agreement. His dreams took him to the West Coast and we tried to make it work long-distance, but it didn't work out. Sometimes the right thing to do is the saddest. Thanks for respecting his privacy. I'll be 60 in a couple of months. Life begins again.

- ^ "Q&A with Andrew Sullivan (see 45:44 to 46:27)". C-SPAN. 4 October 2006. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "The HIV Travel Ban: Still In Place". The Daily Dish. Archived from the original on 31 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "Free at Last". The Daily Dish. 30 October 2009. Archived from the original on 26 December 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ^ "Weekend of April 16–17, 2011 – Videos – The Chris Matthews Show". videos.thechrismatthewsshow.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ "On the Cover: Andrew Sullivan on Becoming an American Citizen". New York Press Room. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (15 September 2017). "Yes, I'm Dependent on Weed". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ Andrew Sullivan (24 April 2005). "The Vicar of Orthodoxy". Time. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (16 December 2011). "Andrew Sullivan Recalls a Memorable Brunch Invitation from Hitchens". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Miniter, Richard. "Christopher Hitchens, As I Knew Him". Forbes. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Andrew (15 August 2010). "Feel the love, Hitch — it will survive you". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 10 January 2024. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

External links

edit- The Weekly Dish, Andrew Sullivan's substack newsletter

- The Dish, Andrew Sullivan's blog

- Column archive (2009–2009) at The Atlantic

- Why I Blog, November 2008

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Andrew Sullivan on Charlie Rose

- Andrew Sullivan at IMDb

- Andrew Sullivan collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- World's Best Blogger?, Harvard Magazine, May–June 2011