The architecture of Lebanon embodies the historical, cultural and religious influences that have shaped Lebanon's built environment. It has been influenced by the Phoenicians, Romans, Byzantines, Umayyads, Crusaders, Mamluks, Ottomans and French [citation needed]. Additionally, Lebanon is home to many examples of modern and contemporary architecture. Architecturally notable structures in Lebanon include ancient thermae and temples, castles, churches, mosques, hotels, museums, government buildings, souks, residences (including palaces) and towers.

Roman architecture

editBaalbeck is counted as one of the Roman treasures in Lebanon, and is home to many ancient Roman temples built at the end of the third millennium B.C.[contradictory][citation needed] The city was referred to as the city of the sun (Heliopolis) by the Greeks.[1]

The temples have faced theft, earthquakes and civil wars and wear. French, German and Lebanese archaeologists rebuilt the temples. In 1984, Baalbek was made a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.[2] They are described as being “the finest example of imperial Roman architecture” [citation needed].

The Jupiter temple is a six Corinthian columns of the great temple, and it is a 22 meters high column built on a podium. In this Temple, only six columns remain out of the 54 massive columns that originally surrounded the sanctuary. The little temple is found near the Jupiter Temple is known as the Temple of Bacchus and it was built in the second century A.D. Finally, it is considered to be the best preserved Roman temple of its size.[3]

Castles

editLebanon is known for its many stone castles.

Cities

editByblos

editByblos is one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world, tracing back to around 8800 years B.C.[4][5] The castle in Byblos, surrounded by a moat, was built by the Crusaders from indigenous limestone and the remains of Roman structures. Saladin captured the town and castle in 1188 and partially dismantled the walls in 1190. Later, the Crusaders recaptured Byblos and rebuilt the fortifications of the castle in 1197.[6]

Sidon

editSidon is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Lebanon, due largely to its historical sites. The two main cultural influences on Sidon were the Egyptian Pharaohs and the Greeks. The city is known for the castle of Sidon which is a castle on the sea that was built in 1228 by Crusaders. The castle was built on the remains of a Phoenician shrine dedicated to the God Melkart. This castle's location falls on an island in the Lebanese city of Saida, it is about 80 meters from the beach, linked by bridge building on a rocky nine barrages. The roof is usually used for sightseeing providing an exquisite view of the port and the old remains of the city. The city Sidon by itself has become a touristic destination because of its value in the history of the country as a whole and for the beauty of its architecture.[7]

Beirut

editArchaeological artifacts show Beirut was settled back to the Iron Age.[8] Beirut was a city of glory during the Roman era. It then became occupied by different civilizations some of which were the Crusaders in 1109, the Mamluks in 1291 and then Ottomans who stayed in Lebanon for 400 years until 1916. The country then went through a period of French mandate until 1943. During this period European architecture was introduced.[citation needed]

Up until the first half of the 19th century it was not as significant as other cities along the Mediterranean Sea coast (Tripoli and Damascus), and few pre-19th century landmarks remain, apart from some religious buildings.[8] In 1831 Ibrahim Pasha established himself in the city in the wake of his struggle against Ottoman rulers.[8] The toll road to Damascus was constructed in 1863, Orozdi Bek Department store in 1900, and the Arts and Crafts School in 1914.[8]

The city now features modern buildings alongside arabesque Ottoman buildings,[citation needed] as well as Roman and Byzantine structures. Beirut is famous for a group of five columns that were discovered underground in the heart of the city in 1963, found to be a small part of a grand colonnade of Roman Berytus.[9]

Religious architecture

editRoman temples include the Temples of Baalbek, and ancient temples in Niha. There Are also a few Ancient Phoenician Temples for example The Temple Of Eshmun, which is dedicated to the Phoenician God Eshmun, The God of Healing. It is located near the Awali river, 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) northeast of Sidon in southwestern Lebanon.

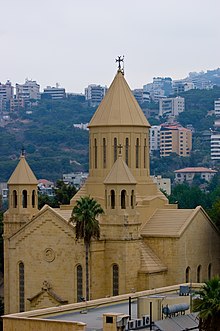

There are thousands of churches in Lebanon that include but are not limited to: Saint George Maronite Cathedral of Beirut, Saint Louis Cathedral, Beirut, Saint George Maronite Cathedral, Beirut, Saint George Greek Orthodox Cathedral, Bzoummar, and St. Elie and St. Gregory the Illuminator Armenian Catholic Cathedral. Deir el Qamar is home to a former synagogue. (Deir el Qamar Synagogue)[citation needed]

19th century

editThe Beit ed-Dine palace complex was built by Amir Bechir El-Chehab II in the early 19th century. The palace entrance leads through the gates into an open space. This area was originally used for cavalry practices and for celebrations, which were attended by the public, visitors and important people of that time. The palace complex is now a museum with pictures, transcripts and documents including a collection of ancient pottery. It also contains a collection of Romanian gold jewelry, Islamic glazed wares, ethnographic objects, and ancient and modern weapons.[10]

Major building projects during Ottoman times included the Grand Serail (1853), an Ottoman Bank (1856, closed 1921), Capucine St. Louise (1863), Petit Serail (1884), Beirut train station (1895), Ottoman Clock Tower (1898) and an Ottoman department store (1900).[11] Outside the city walls, Syrian Protestant College (which became American University of Beirut in 1920) opened in 1866.[11] In 1883 the Jesuits also opened a university on the city's edge (Saint Joseph University).[11] New primary and secondary schools were also established.[11]

20th century and Classical architecture to Modernism

edit20th century architecture in Lebanon included the period of the French Mandate (1918–1943) and independent periods. Lebanon and Beirut in particular has seen large scale developments in recent decades, especially after the civil war ended.[12] Some historic sites have been lost as new buildings are erected.[12] Swiss architect Addor et Juilliard designed the Central Bank building. Maurice Hindieh designed the Ministry of Defense building (1965) and Andre Wogenscky Lebanese University (1960s).[8] The Museum of the Resistance is in Mleeta. Artisans House (1963) in Ain-Mreisseh and Electricite du Liban headquarters in Beirut. Monastery of Unity in Yarze, School of Ain Najm, and SNA-Assurances headquarters (1970) in Beirut are other modernist examples.

Contemporary architecture

editInternational architecture firms have also played a role and 21st century projects include the New Beirut Souks by Rafael Moneo, Hariri Memorial Garden[13] and Zaitunay Bay. The Arab Center for Architecture (ACA) was established in Beirut in 2008.[14] VJAA designed the Charles Hostler Center (2008) in Beirut.[15]

Residential architecture

editThe first residential houses in Lebanon were the Phoenician houses.[16] They were bricks and the roofs where always formed from massive rocky segments. The perception deriving the method of building a house met some changes after the third millennium BC when the walls of the houses increased in height, some houses were built with stones, others remained rectangular and all increased in dimensions.[citation needed] The exterior and the interior walls where covered sometimes with mud.[citation needed]

Lebanese houses incorporated the rules of the Ottoman Empire and the exit of the French mandate.

Architects

editProminent architects who worked in Lebanon include:

- Bechara Affendi, an Armenian-Lebanese architect who designed Petit Serail, Menchiyyeh and the Police and Internal Security Headquarters (demolished in the early 1990s)[11]

- Youssef Aftimus, Beirut City Hall (1933)[8]

- Mardiros Altounian[8] (1889-1958), a graduate of the Ecole des Beaux Arts (1918) he designed Lebanese Parliament (1931), Abed clock tower (1934) in Nejmeh Square, Armenian Sanatorium of Azounieh (1937) in the Chouf region,[12] and National Museum buildings.[8]

- Ilyas Murr (1884–1976), the first Lebanese engineer to graduate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1905), he designed the Art Deco Roxy movie theater (1932) in central Beirut.[12]

- Antoine Tabet (1907–1964) graduated from the Ecole Superieure des Ingenieurs de Beyrouth in 1926 and worked in Paris under Auguste Perret until 1932 when he joined Jacques Poirrier, Georges Bordes and Andre Lotte to design the Hotel Saint Georges. He also designed the Almaza beer factory (1934), and Sagesse School (1937) in Achrafieh. Tabet and Farid Trad were Modernist pioneers in Lebanon.[12]

- Karol Schayer (1900–1971), a graduates of the Polytechnic School of Lvov in 1920, emigrated to Lebanon during World War II. He teamed with German interior designer Fritz Gotthelf (1905–1980), Wassek Adib (1926–) and engineer Bahij Makdissi (1916–1995) to establish an architectural firm that designed the AUB Alumni Club (1952), Dar al Sayad (1954), and the Shell building (1959).[12]

- Michel Ecochard (1905–1985) a graduated of the Ecole des Beaux Arts who developed the first master plan of Beirut to be implemented (1943). With Claude Lecoeur he designed the College Protestant (1955) on Marie Curie Street and went on to design the Grand Lycee Franco-Libanais (1960), and Sacre-coeur Hospital (1961) in Hazmieh.[12]

- Andre Leconte (1894–1990) designed the Beirut International Airport (1948–1954) at Khalde and also designed the Lazarieh office building (1953) in downtown Beirut and Rizk Hospital (1957] in Achrafieh.[12]

- George Addor (1920–1982) a graduate of the Zurich Polytechnic school (1948) designed the Starco Center (1957) with his partner Dominique Julliard as well as the Central Bank building and the presidential palace (1965) in Baabda[12]

- Joseph Phillippe Karam[11]

- George Rayyes (1915–2002), born in Alexandria, Egypt and attended the Bartlett School and the Architecture Association went on to design several projects with partners Theo Kanaan (1910–1959) and Assem Salam including the Pan American Building (1955) in the center of the city.[12] He also designed Arida Apartment Building (1951) with Theo Kanaan.[11]

- Oscar Niemeyer, from Brazil designed the Tripoli, Lebanon, Tripoli International Fair or Rashid Karami Fair (begun in 1963 and still unfinished during the beginning of the civil war in 1975)[12]

- Assem Salam (born 1924), a graduate of the University of Cambridge (1950) he designed the Serail of Saîda (1965), Khachoggi Mosque (1968), Broumana High School dormitories (1966)[12] He worked with George Rayyes and Theo Kanaan, and went on to be involved in the design in many important buildings.[11]

- Michel Abboud

- Pierre el-Khoury (1930–2005), known as "Sheikh Pierre", studied at Ecole Nationale des Beaux Arts (1957), returned to Lebanon and designed more than 200 buildings including Ghazal Tower, Moritra residential building[8][17] British Bank in Beirut and basilica at Our Lady of Lebanon in Harissa, Lebanon.[11]

- Joseph Philippe Karam

- Zaha Hadid American University in Beirut buildings

- Other architects who have helped shape Lebanon include Khalil Khoury (1929–), his brother Georges Khoury (1933–), Gregoire Serof, Raoul Verney, Jacques Liger-Belair, Pierre Neema, Antoine Romanos,[12] Pierre Neema, Karl Cheyer, Fritz Gotthelf, Bahij Makdisi, Habib Debs, Jad Tabet, Jalal El-Ali, and Wassek Adib.[11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Baalbek: Heliopolis, city of the sun, p. 15. Dar el-Machreq Publishers : distribution, Librairie Orientale. Retrieved 12 November 2011

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Review describing Baalbek

- ^ Ballbek Info, Middle east countries, Retrieved on 18 November 2011

- ^ Byblos Info, Middle east cities, Retrieved 19 November 2011

- ^ E. J. Peltenburg; Alexander Wasse; Council for British Research in the Levant (2004). Garfinkel, Yosef., "Néolithique" and "Énéolithique" Byblos in Southern Levantine Context* in Neolithic revolution: new perspectives on southwest Asia in light of recent discoveries on Cyprus. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-132-5. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- ^ "Byblos Castle". Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Aḥmad ʻĀrif Zayn, (Sidon's history) تاريخ صيدا, Princeton University Arabic collection, مطبعة العرفان 1913

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Architecture edited by Stephen Sennott pages 128- 130

- ^ Samir Kassir, Malcolm Debevoise, Robert Fisk, Beirut University of California Press, University of California Press, 2010

- ^ Beit ed-Dine بيت الدين, barelias Archived November 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on 20 November 2011

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Heart of Beirut: Reclaiming the Bourj by Samir Khalaf

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-08-07. Retrieved 2015-07-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Hariri Memorial Garden by Vladimir Djurovic Archived July 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Architecture Lab

- ^ About Arab Center for Architecture

- ^ "Charles Hostler Center / VJAA". 29 September 2009.

- ^ Peter Rainow, HISTORY OF LEBANON Greenwood histories of the modern nations, Greenblood Pub Group, 2010

- ^ Distinguished architect Pierre El-Khoury leaves a dazzling visual legacy July 8, 2005 The Daily Star (Lebanon)

Further reading

edit- A dictionary of 20th century architecture in Lebanon, Alphamedia, Beirut by Yacoube G., 2004.