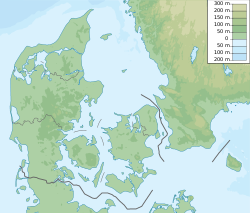

Aarhus (/ˈɔːrhuːs/, US also /ˈɑːr-/,[3][4][5][6] Danish: [ˈɒːˌhuˀs] ; officially spelled Århus from 1948 until 1 January 2011)[7][note 1] is the second-largest city in Denmark and the seat of Aarhus Municipality. It is located on the eastern shore of Jutland in the Kattegat sea and approximately 187 kilometres (116 mi) northwest of Copenhagen.

Aarhus | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Nickname: Smilets by (City of smiles) | |

Aarhus Denmark Street Map | |

| Coordinates: 56°09′N 10°13′E / 56.150°N 10.217°E | |

| Country | Denmark |

| Region | Central Denmark Region (Midtjylland) |

| Municipality | Aarhus |

| Established | 8th century |

| City Status | 15th century |

| Named for | Aarhus River mouth |

| Government | |

| • Type | Magistrate |

| • Mayor | Jacob Bundsgaard (S) |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 99.4 km2 (38.4 sq mi) |

| • Municipal | 468 km2 (181 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 105 m (344 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2024)[2] | |

| • Rank | Denmark: 2nd |

| • Urban | 295,688 |

| • Urban density | 2,975/km2 (7,710/sq mi) |

| • Municipal | 367,095 |

| • Municipal density | 784/km2 (2,030/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Aarhusianer |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 8000, 8200, 8210, 8220, 8230 |

| Area code | (+45) 8 |

| Website | Official website |

Dating back to the late 8th century, Aarhus was founded as a harbour settlement at the mouth of the Aarhus River and quickly became a trade hub. The first Christian church was built here around the year 900 and later in the Viking Age the town was fortified with defensive ramparts. The bishopric of Aarhus grew steadily stronger and more prosperous, building several religious institutions in the town during the early Middle Ages. Trade continued to improve, although it was not until 1441 that Aarhus was granted market town privileges, and the population of Aarhus remained relatively stable until the 19th century. The city began to grow significantly as trade prospered in the mid-18th century, but not until the mid-19th century did the Industrial Revolution bring real growth in population. The first railway line in Jutland was built here in 1862. In 1928, the first university in Jutland was founded in Aarhus and today it is a university city and the largest centre for trade, services, industry, and tourism in Jutland.

Aarhus Cathedral is the longest cathedral in Denmark with a total length of 93 m (305 ft). The Church of our Lady (Vor Frue Kirke) was originally built in 1060, making it the oldest stone church in Scandinavia. The City Hall, designed by Arne Jacobsen and Erik Møller, was completed in 1941 in a modern Functionalist style. Aarhus Theatre, the largest provincial theatre in Denmark, opposite the cathedral on Bispetorvet, was built by Hack Kampmann in the Art Nouveau style and completed in 1916. Musikhuset Aarhus (concert hall) and Det Jyske Musikkonservatorium (Royal Academy of Music, Aarhus/Aalborg) are also of note, as are its museums including the open-air museum Den Gamle By, the art museum ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, the Moesgård Museum and the women's museum Kvindemuseet. The city's major cultural institutions include Den Gamle By, ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, the Moesgård Museum, Gender Museum Denmark, Musikhuset Aarhus and Aarhus Theatre. Known as Smilets By (lit. City of Smiles) it is the Danish city with the youngest demographics and home to Scandinavia's largest university, Aarhus University.[2][8] Commercially, the city is the principal container port in the country, and major Danish companies such as Vestas, Arla Foods, Salling Group, and Jysk have their headquarters there.

Etymology

Aarhus is a compound of the two Old Norse words; ár, genitive of á ("river", Modern Danish å), and oss ("mouth") referencing the city's location at the mouth of Aarhus Å (Aarhus River).[9][10][11]

Spelling

In Valdemar's Census Book (1231) the city was called Arus, and in Icelandic it was known as Aros, later written as Aars.[12] The spelling "Aarhus" is first found in 1406 and gradually became the norm in the 17th century.[12] With the Danish spelling reform of 1948, "Aa" was changed to "Å". Some Danish cities resisted the change but Aarhus city council opted to change the name.[13] In 2010, the city council voted to change the name back from Århus to Aarhus again with effect from 1 January 2011.[14]

It is still grammatically correct to write geographical names with the letter Å and local councils are allowed to use the Aa spelling as an alternative and most newspapers and public institutions will accept either. Some official authorities such as the Danish Language Committee, publisher of the Danish Orthographic Dictionary, still retain Århus as the main name, providing Aarhus as a second option, in brackets[7] and some institutions are still using Århus explicitly in their official name, such as the local newspaper Århus Stiftstidende and the schools Århus Kunstakademi and Århus Statsgymnasium. "Aa" was used by some major institutions between 1948 and 2011 as well, such as Aarhus University or the largest local sports club, Aarhus Gymnastikforening (AGF), which has never used the "Å" spelling.[15] Certain geographically affiliated names have been updated to reflect the name of the city, such as the Aarhus River, changed from Århus Å to Aarhus Å.[9]

History

Early history

Founded in the early Viking Age, Aarhus is one of the oldest cities in Denmark, along with Ribe and Hedeby.[16] The original Aros settlement was situated on the northern shores of a fjord by the mouth of the Aarhus River, right where the city center is today. It quickly became a hub for sea-going trade due to its position on intersecting trade routes in the Danish straits and the fertile countryside. The trade, however, was not nearly as prominent as that in Ribe and Hedeby during the Viking Age, and it was primarily linked to Norway as evidenced by archaeological finds. A shipbuilding yard from the Viking Age was uncovered upriver in 2002 by archaeologists. It was located at a place formerly known as Snekkeeng, or Snekke Meadow in English ('Snekke' is a type of longship), east of the Brabrand Lake close to Viby, and it was in use for more than 400 years from the late 700s till around the mid-1200s.[17]

Archaeological evidence indicates that Aarhus was a town as early as the last quarter of the 8th century.[18][19] Discoveries after a 2003 archaeological dig included half-buried longhouses, firepits, glass pearls and a road dated to the late 700s.[20] Several excavations in the inner city since the 1960s have revealed wells, streets, homes and workshops, and inside the buildings and adjoining archaeological layers, everyday utensils like combs, jewellery and basic multi-purpose tools from approximately the year 900 have been unearthed.[21] The early town was fortified with defensive earthen ramparts in the first part of the 900s, possibly in the year 934 on order from king Gorm the Old. The fortifications were later improved and expanded by his son Harald Bluetooth, encircling the settlement much like the defence structures found at Viking ring fortresses elsewhere.[18] Together with the town's geographical placement, this suggests that Aros became an important military centre in the Viking Age. There are also strong indications of a former royal residence from the same period in Viby, a few kilometres south of the Aarhus city centre.[22][23]

The centre of Aarhus was originally a pagan burial site until Aarhus's first Christian church, Holy Trinity Church, a timber structure, was built upon it during the reign of Frode, King of Jutland, around 900.[24] The bishopric of Aarhus dates back to at least 948 when Adam of Bremen reported that the missionary bishop Reginbrand of Aros attended the synod of Ingelheim in Germany,[25][26] but the late Viking Age during the Christianization of Scandinavia was a turbulent and violent time with several naval attacks on the town, such as Harald Hardrada's assault around 1050, when the Holy Trinity Church was burned to the ground.[18][27] Despite the conflicts, Aarhus continued to prosper from the trade and the finding of six runestones in and around Aarhus indicates the city had some significance around the year 1000, as only wealthy nobles traditionally used them.[28] The bishopric diocese was obliterated for almost a hundred years after Reginbrand in 988, but in 1060 a new bishop Christian was ordained and he founded a new church in Aarhus, Sankt Nicolai Domkirke (St. Nicholas Cathedral), this time in stone. It was erected outside the town fortifications, and stood finished in 1070 at the site where Church of Our Lady stands today, but only an underground crypt remains.[29][30]

Middle Ages

The growing influence of the Church during the Middle Ages gradually turned Aarhus, with its bishopric, into a prosperous religious centre. Many public and religious buildings were built in and around the town; notably Aarhus Cathedral was initiated in the late 12th century by the influential bishop Peder Vognsen, and around 1200, Aros had a total of four churches. The 13th century also marks a thorough reorganisation, erasing most of the town's original layout with new streets, relocations, dismantling and new constructions. The Church clearly had the upper hand in the Aarhus region during medieval times, and the large bishopric of Aarhus prospered and expanded territory, reaching as far as Viborg in extent.[17] In 1441, Christopher III issued the oldest known charter granting market town status, although similar privileges may have existed as far back as the 12th century. The charter is the first official recognition of the town as a regional power and is by some considered Aarhus's birth certificate.[29][31]

The commercial and religious status spurred town growth, and in 1477 the defensive earthen ramparts, which had ringed the town since the Viking Age, were abandoned to accommodate expansion. Parts of the ramparts still exist today and can be experienced as steep slopes at the riverside, and they have also survived in some place names of the inner city, including the streets of Volden (The Rampart) and Graven (The Moat).[32][33] Aarhus grew to become one of the largest cities in the country by the early 16th century. In 1657, octroi was imposed in larger Danish cities which changed the layout and face of Aarhus over the following decades. Wooden city walls were erected to prevent smuggling, with gates and toll booths on the major thoroughfares, Mejlgade and Studsgade. The city gates funnelled most traffic through a few streets where merchant quarters were built.[34]

In the 17th century, Aarhus entered a period of recession as it suffered blockades and bombardments during the Swedish wars and trade was dampened by the preferential treatment of the capital by the state.[35] Not until the middle of the 18th century did growth return, in large part due to trade with the large agricultural catchment areas around the city; grain, particularly, proved to be a remunerative export.[29] The first factories were established at this time, as the Industrial Revolution reached the country, and in 1810 the harbour was expanded to accommodate growing trade.[36]

Industrialisation

Aarhus began to prosper in the 1830s as the industrial revolution reached the city and factories with steam-driven machinery became more productive.[37] In 1838, the electoral laws were reformed leading to elections for the 15 seats on the city council. The rules were initially very strict, allowing only the wealthiest citizens to run. In the 1844 elections, only 174 citizens qualified out of a total population of more than 7,000.[38] The first city council, mainly composed of wealthy merchants and industrialists, quickly looked to improve the harbour, situated along the Aarhus River. Larger ships and growing freight volumes made a river harbour increasingly impractical. In 1840, the harbour was moved to the coast, north of the river, where it became the largest industrial harbour outside Copenhagen over the following 15 years. From the outset, the new harbour was controlled by the city council, as it is to this day.[39]

During the First Schleswig War, Aarhus was occupied by German troops from 21 June to 24 July 1849. The city was spared any fighting, but in Vejlby north of the city a cavalry skirmish known as Rytterfægtningen took place which stopped the German advance through Jutland.[40] The war and occupation left a notable impact on the city as many streets, particularly on Frederiksbjerg, are named after Danish officers of the time. Fifteen years later, in 1864, the city was occupied again, this time for seven months, during the Second Schleswig War.[41][42]

In spite of wars and occupation, the city continued to expand and develop. In 1851, the octroi was abolished and the city walls were removed to provide easier access for trade. Regular steamship links with Copenhagen had begun with the Jylland in 1825–26 and the Dania (1827–36), and in 1862 Jutland's first railway was established between Aarhus and Randers.[43][39]

In the second half of the 19th century, industrialisation came into full effect and a number of new industries emerged around production and refinement of agricultural products, especially oil and butter. Many companies from this time would come to leave permanent iconic marks on Aarhus. The Ceres Brewery was established in 1856 and served as Aarhus's local brewery for more than 150 years, gradually expanding into an industrial district known as Ceres-grunden (lit.: the Ceres-ground).[44][45][46] In 1896, local farmers and businessmen created Korn- og Foderstof Kompagniet (KFK), focused on grain and feedstuffs. KFK established departments all over the country, while its headquarters remained in Aarhus where its large grain silos still stand today.[47][48] Otto Mønsted created the Danish Preserved Butter Company in 1874, focusing on butter export to England, China and Africa and later founded the Aarhus Butterine Company in 1883, the first Danish margarine factory.[49] His company became an important local employer, with factory employees increasing from 100 in 1896 to 1,000 in 1931, partaking in the effective transformation of the city from a regional trade hub to an industrial centre.[50] Other new factories of note included the dockyard Aarhus Flydedok and the oil mill Århus Oliefabrik.[51]

Aarhus became the largest provincial city in the country by the turn of the century and the city marketed itself as the "Capital of Jutland". The population increased from 15,000 in 1870 to 52,000 in 1901 and, in response, the city annexed large land areas to develop new residential quarters such as Trøjborg, Frederiksbjerg and Marselisborg.[52] Many of its cultural institutions were also established at this time such as Aarhus Theatre (1900), the original State Library (1902), Aarhus University (1928) and several hospitals.[53]

Second World War

On 9 April 1940, Nazi Germany invaded Denmark, occupying Aarhus the following day; the occuption lasted for five years. This was a destructive period with major disasters, loss of life and economic depression. The Port of Aarhus became a hub for supplies to the Baltics and Norway, while the surrounding rail network supplied the Atlantic Wall in west Jutland and cargo headed for Germany. Combined, these factors resulted in a strong German presence, especially in 1944–45.[54]

Small resistance groups first appeared in 1941–42 but the first to co-ordinate with the Freedom Council was the Samsing Group, responsible for most operations from early 1943.[55][56] The Samsing group, along with others in and around Aarhus, was dismantled in June 1944 when Grethe "Thora" Bartram turned her family and acquaintances over to German authorities.[57] In response, requests for assistance were sent to contacts in England and in October 1944 the Royal Air Force bombed the Gestapo headquarters successfully destroying archives and obstructing the ongoing investigation.[58][59]

In the summer of 1944 the Copenhagen-based resistance group Holger Danske helped establish the 5 Kolonne group and an SOE agent arrived from England to liaison with the L-groups.[60] Subsequently, resistance operations escalated which was countered with Schalburgtage terror operations by the Peter group.[61][62] The increasingly destructive occupation was compounded when an ammunition barge exploded in July 1944, destroying much of the harbour area.[63] On 5 May 1945 German forces in Denmark surrendered but during the transitional period fighting broke out resulting in 22 dead.[64] On 8 May the British Royal Dragoons entered the city.[65]

Post-World War II years

In the 1970s and 1980s the city entered a period of rapid economic growth and the service sector overtook trade, industry and crafts as the leading sector of employment for the first time.[66] Workers gradually began commuting to the city from most of east and central Jutland as the region became more interconnected. The student population tripled between 1965 and 1977 turning the city into a Danish centre of research and education.[67] The growing and comparably young population initiated a period of creativity and optimism; Gaffa and the KaosPilot school were founded in 1983 and 1991 respectively, and Aarhus was at the centre of a renaissance in Danish rock and pop music launching bands and musicians such as TV2, Gnags, Thomas Helmig, Bamses Venner, Anne Dorte Michelsen, Mek Pek and Shit & Chanel.[68][69][70]

The 2000s

Since the turn of the millennium, Aarhus has seen an unprecedented building boom with many new institutions, infrastructure projects, city districts and recreational areas. Several of the construction projects are among the largest in Europe, such as the New University Hospital (DNU) and the harbourfront redevelopment.[71][72]

Both the skyline and land use of the inner city is changing, as former industrial sites are being redeveloped into new city districts and neighbourhoods. Starting in 2008, the former docklands known as De Bynære Havnearealer (The Peri-urban Harbour-areas), and closest to the city seaside, are being converted to new mixed-use districts. It is among the largest harbourfront projects in Europe. The northern part dubbed Aarhus Ø (Aarhus Docklands) is almost finished as of 2018, while the southern district dubbed Sydhavnskvarteret (The South-harbour neighbourhood) is only starting to be developed.[73][74][75] The adjacent site of Frederiks Plads at the former DSB repair facilities have been under construction since 2014 as a new business and residential quarter.[76][77][78] The main bus terminal close by is planned to be moved to the central railway station and the site will be redeveloped to a new residential neighbourhood.[79][80] Elsewhere in the inner city, the site of the former Ceres breweries was redeveloped in 2012–2019 as a new mixed use neighbourhood known as CeresByen.[81]

Construction of Aarhus Letbane, the first light rail system in the country, commenced in 2013, and the first increment was finished in December 2017.[82] Since then, the lightrail service has been expanded with two intercity sections to the towns of Odder and Grenå, respectively, and also includes a northward leg to the suburb of Lisbjerg.[83][84] The light rail system is planned to tie many other suburbs closer to central Aarhus in the future, with the next phase including local lines to Brabrand in the east and Hinnerup to the north.[85]

Accelerating growth since the early 2000s, brought the inner urban area to roughly 260,000 inhabitants by 2014. The rapid growth is expected to continue until at least 2030 when Aarhus municipality has set an ambitious target for 375,000 inhabitants.[86]

Geography

Aarhus is located at the Bay of Aarhus facing the Kattegat sea in the east with the peninsulas of Mols and Helgenæs across the bay to the northeast. Mols and Helgenæs are both part of the larger regional peninsula of Djursland. A number of larger cities and towns is within easy reach from Aarhus by road and rail, including Randers (38.5 kilometres (23.9 mi) by road north), Grenå (northeast), Horsens (50 kilometres (31 mi) south) and Silkeborg (44 kilometres (27 mi) east).[87]

Topography

At Aarhus's location, the Bay of Aarhus provides a natural harbour with a depth of 10 m (33 ft) quite close to the shore.[35] Aarhus was founded at the mouth of a brackish water fjord, but the original fjord no longer exists, as it has gradually narrowed into what is now the Aarhus River and the Brabrand Lake, due to natural sedimentation. The land around Aarhus was once covered by forests, remains of which exist in parts of Marselisborg Forest to the south and Riis Skov to the north.[88][89] Several lakes extend west from the inner city as the landscape merges with the larger region of Søhøjlandet with heights exceeding 152 metres (499 ft) at Himmelbjerget between Skanderborg and Silkeborg.[90] The highest natural point in Aarhus Municipality is Jelshøj at 128 metres above sea level, in the southern district of Højbjerg. The hilltop is home to a Bronze Age barrow shrouded in local myths and legends.[91]

The hilly area around Aarhus consists of a morainal plateau from the last ice age, broken by a complex system of tunnel valleys. The most prominent valleys of this network are the Aarhus Valley in the south, stretching inland east–west with the Aarhus River, Brabrand Lake, Årslev Lake and Tåstrup Lake, and the Egå Valley to the north, with the stream of Egåen, Egå Engsø, the bog of Geding-Kasted Mose and Geding Lake. Most parts of the two valleys have been drained and subsequently farmed, but in the early 2000s some of the drainage was removed and parts of the wetlands were restored for environmental reasons. The valley system also includes the stream of Lyngbygård Å in the west and valleys to the south of the city, following erosion channels from the pre-quaternary. By contrast, the Aarhus River Valley and the Giber River Valley are late glacial meltwater valleys. The coastal cliffs along the Bay of Aarhus consist of shallow tertiary clay from the Eocene and Oligocene (57 to 24 million years ago).[92][93][94][95]

Climate

| East Jutland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Aarhus has a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb)[97] and the weather is constantly influenced by major weather systems from all four ordinal directions, resulting in unstable conditions throughout the year.[98] Temperature varies a great deal across the seasons with a mild spring in April and May, warmer summer months from June to August, frequently rainy and windy autumn months in October and September and cooler winter months, often with frost and occasional snow, from December to March. The city centre experiences the same climatic effects as other larger cities with higher wind speeds, more fog, less precipitation and higher temperatures than the surrounding, open land.[99]

Western winds from the Atlantic and North Sea are dominant resulting in more precipitation in western Denmark. In addition, Jutland rises sufficiently in the centre to lift air to higher, colder altitudes contributing to increased precipitation in eastern Jutland. Combined, these factors make east and south Jutland comparatively wetter than other parts of the country.[96] Average temperature over the year is 8.43 °C (47.17 °F) with February being the coldest month (0.1 °C or 32.2 °F) and August the warmest (15.9 °C or 60.6 °F). Temperatures in the sea can reach 17–22 °C (63–72 °F) in June to August, but it is not uncommon for beaches to register 25 °C (77 °F) locally.[99][100]

The geography in the area affects the local climate of the city with the Aarhus Bay imposing a temperate effect on the low-lying valley floor where central Aarhus is located. Brabrand Lake to the west further contributes to this effect and as a result, the valley has a comparably mild, temperate climate. The sandy ground on the valley floor dries up quickly after winter and warms faster in the summer than the surrounding hills of moist-retaining boulder clay. These conditions affect crops and plants that often bloom 1–2 weeks earlier in the valley than on the northern and southern hillsides.[101]

Because of the northern latitude, the number of daylight hours varies considerably between summer and winter. On the summer solstice, the sun rises at 04:26 and sets at 21:58, providing 17 hours 32 minutes of daylight. On the winter solstice, it rises at 08:37 and sets at 15:39 with 7 hours and 2 minutes of daylight. The difference in length of days and nights between summer and winter solstices is 10 hours and 30 minutes.[102]

| Climate data for East Jutland (Tirstrup) (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

2.5 (36.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.8 (69.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

11.8 (53.2) |

6.9 (44.4) |

4.1 (39.4) |

11.4 (52.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.2 (32.4) |

0.1 (32.2) |

2.3 (36.1) |

5.8 (42.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

15.9 (60.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

8.7 (47.7) |

4.4 (39.9) |

1.8 (35.2) |

7.7 (45.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.7 (27.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

1.2 (34.2) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.3 (52.3) |

11.8 (53.2) |

7.8 (46.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 60 (2.4) |

41 (1.6) |

48 (1.9) |

42 (1.7) |

50 (2.0) |

55 (2.2) |

67 (2.6) |

65 (2.6) |

72 (2.8) |

77 (3.0) |

80 (3.1) |

68 (2.7) |

722 (28.4) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1mm) | 11 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 12 | 120 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 41 | 75 | 141 | 207 | 254 | 251 | 243 | 239 | 165 | 101 | 65 | 45 | 1,827 |

| Source: "Danish Meteorological Institute". | |||||||||||||

Politics and administration

Aarhus is the seat of Aarhus Municipality, and Aarhus City Council (Aarhus Byråd) is also the municipal government with headquarters in Aarhus City Hall. The Mayor of Aarhus since 2010 is Jacob Bundsgaard of the Social Democrats.[103] Municipal elections are held every fourth year on the third Tuesday of November with the next election in 2021. The city council consists of 31 members elected for four-year terms. When an election has determined the composition of the council, it elects a mayor, two deputy mayors and five aldermen from their ranks.[104] Anyone who is eligible to vote and who resides within the municipality can run for a seat on the city council provided they can secure endorsements and signatures from 50 inhabitants of the municipality.[105]

The first publicly elected mayor of Aarhus was appointed in 1919. In the 1970 Danish Municipal Reform the current Aarhus municipality was created by merging 20 municipalities.[106] Aarhus was the seat of Aarhus County until the 2007 Danish municipal reform, which substituted the Danish counties with five regions and replaced Aarhus County with Central Denmark Region (Region Midtjylland), seated in Viborg.[107]

Subdivisions

Aarhus Municipality has 45 electoral wards and polling stations in four electoral districts for the Folketing (national Parliament).[108] The diocese of Aarhus has four deaneries composed of 60 parishes within Aarhus municipality.[109] Aarhus municipality contains 21 postal districts and some parts of another 9.[110] The urban area of Aarhus and the immediate suburbs are divided into the districts Aarhus C, Aarhus N, Aarhus V, Viby J, Højbjerg and Brabrand.[111]

Environmental planning

Aarhus has increasingly been investing in environmental planning and, in accordance with national policy, aims to be CO

2-neutral and independent of fossil fuels for heating by 2030.[112][113] The municipal power plants were adapted for this purpose in the 2010s. In 2015, the municipality took over three private straw-fired heating plants and the year after, a new 77 MW combined heat and power biomass plant at Lisbjerg Power Station was completed while Studstrup Power Station finished a refit to move from coal to wood chips.[114][115] In conjunction with the development of the Docklands district there are plans for a utility-scale seawater heat pump which will take advantage of fluctuating electricity prices to supply the district heating system.[116] Since 2015, the city has been implementing energy-saving LED technology in street lighting; by January 2019, about half of the municipal street lighting had been changed. Apart from reducing the city's CO2 emissions, it saves 30% on the electricity bill, thereby making it a self-financed project over a 20-year period.[117]

The municipality aims for a coherent and holistic administration of the water cycle to protect against, and clean up previous, pollution as well as encourage green growth and self-sufficiency. The main issues are excessive nutrients, adapting to increased (and increasing) levels of precipitation brought on by climate change, and securing the water supply.[118] These goals have manifested in a number of large water treatment projects often in collaboration with private partners. In the 2000s, underground rainwater basins were built across the city while the two lakes Årslev Engsø and Egå Engsø were created in 2003 and 2006 respectively. The number of sewage treatment plants is planned to be reduced from 17 to 2 by 2025, as the treatment plants in Marselisborg and Egå are scheduled for expansion to take over all waste water treatment. They have already been refitted for biogas production to become net producers of electricity and heat.[119][120] To aid the new treatment plants, and avoid floodings, sewage and stormwater throughout the municipality is planned to be separated into two different drainage systems. Construction began in 2017 in several areas, but it is a long process that is scheduled to be finished by 2085.[121][122]

Afforestation projects have been undertaken to prevent groundwater pollution, secure drinking water, sequester CO

2, increase biodiversity, create an attractive countryside, provide easy access to nature and offer outdoor activities to the public. In 2000, the first project, the New Forests of Aarhus, was completed, which aimed to double the forest cover in the municipality and, in 2009, another phase was announced to double forest cover once more before the year 2030.[123] The afforestation plans were realised as a local project in collaboration with private landowners, under a larger national agenda.[124] Other projects to expand natural habitats include a rewilding effort in Geding-Kasted Bog and continuous monitoring of the four Natura 2000 areas in the municipality.[125]

Demographics

| Nationality | Population in 2017 | Population in 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| Lebanon | 5,030 | 5,240 |

| Somalia | 4,554 | 4,905 |

| Turkey | 4,370 | 4,362 |

| Iraq | 3,688 | 3,916 |

| Iran | 2,577 | 3,043 |

| Vietnam | 2,551 | 2,578 |

| Germany | 2,261 | 2,551 |

| Poland | 2,235 | 2,672 |

| Afghanistan | 2,092 | 2,591 |

| Romania | 1,983 | 2,678 |

Aarhus has a population of 261,570 on 91 square kilometres (35 sq mi) for a density of 2,874/km2 (7,444/sq mi).[2] Aarhus municipality has a population of 330,639 on 468 km2 with a density of 706/km2 (1,829/sq mi). Less than a fifth of the municipal population resides beyond city limits and almost all live in an urban area.[128] The population of Aarhus is both younger and better-educated than the national average which can be attributed to the high concentration of educational institutions.[129] More than 40% of the population have an academic degree while only some 14% have no secondary education or trade.[130] The largest age group is 20- to 29-year-olds and the average age is 37.5, making it the youngest city in the country and one of its youngest municipalities.[131][132] Women have slightly outnumbered men for many years.[131]

The city is home to 75 different religious groups and denominations, most of which are Christian or Muslim with a smaller number of Buddhist, Hindu, and Jewish communities. Since the 1990s there has been a marked growth in diverse new spiritual groups although the total number of followers remains small.[134] The majority of the population are members of the Protestant state church, Church of Denmark, which is by far the largest religious institution both in the city and the country as a whole. Some 20% of the population are not officially affiliated with any religion, a percentage that has been slowly rising for many years.[135]

During the 1990s there was significant immigration from Turkey and in the 2000s, there was a fast growth in the overall immigrant community, from 27,783 people in 1999 to 40,431 in 2008.[136] The majority of immigrants have roots outside Europe and the developed world, comprising some 25,000 people from 130 different nationalities, with the largest groups coming from the Middle East and North Africa. Some 15,000 have come from within Europe, with Poland, Germany, Romania and Norway being the largest contributors.[131]

Many immigrants have established themselves in the suburbs of Brabrand, Hasle and Viby, where the percentage of inhabitants with foreign origins has risen by 66% since 2000. This has resulted in a few so-called ghettos, defined as residential areas with more than half of inhabitants from non-Western countries and with relatively high levels of poverty and/or crime. Gellerup is the most notable neighbourhood in that respect. The ghetto-labelling has been criticized as unnecessarily stigmatising and counterproductive for social and economical development of the related areas.[137] [138] [139]

| Population groups | Year | |

|---|---|---|

| 2023[140][141] | ||

| Number | % | |

| Danish descent | 295,687 | 81.62% |

| Immigrants | 48,207 | 13.31% |

| EU-27 | 15,940 | 4.4% |

| Europe outside EU-27 | 11,386 | 3.14% |

| Africa | 8,576 | 2.37% |

| North America | 956 | 0.26% |

| South and Central America | 1,866 | 0.52% |

| Asia | 27,501 | 7.59% |

| Oceania | 259 | – |

| Stateless | – | |

| Unknown | – | |

| Total | 362,266 | 100% |

Economy

The economy of Aarhus is predominantly knowledge- and service-based, strongly influenced by the University of Aarhus and the large healthcare industry. The service sector dominates the economy and is growing as the city transitions away from manufacturing. Trade and transportation remain important sectors, benefiting from the large port and central position on the rail network. Manufacturing has been in slow but steady decline since the 1960s while agriculture has long been a marginal sector within the municipality.[142] The municipality is home to 175,000 jobs with some 100,000 in the private sector and the rest split between state, region and municipality.[143] The region is a major agricultural producer, with many large farms in the outlying districts.[144] People commute to Aarhus from as far away as Randers, Silkeborg and Skanderborg and almost a third of those employed within the Aarhus municipality commute from neighbouring communities.[145][146][147] Aarhus is a centre for retail in the Nordic and Baltic countries, with expansive shopping centres, the busiest commercial street in the country and a dense urban core with many speciality shops.[148][149]

The job market is knowledge- and service-based, and the largest employment sectors are healthcare and social services, trade, education, consulting, research, industry and telecommunications.[143] The municipality has more high- and middle-income jobs, and fewer low-income jobs, than the national average.[143] Today, te majority of the largest companies in the municipality are in the sectors of trade, transport and media.[150] The wind power industry has strong roots in Aarhus and the larger region of Central Jutland, and nationally, most of the revenue in the industry is generated by companies in the greater Aarhus area. The wind industry employs about a thousand people within the municipality, making it a central component in the local economy.[151] The biotech industry is well-established in the city, with many small- and medium-sized companies mainly focused on research and development.[152] There are multiple Big Tech companies with offices in the city, including Uber and Google.[153]

Several major companies are headquartered in Aarhus, including four of the ten largest in the country. These include Arla Foods, one of the largest dairy groups in Europe, Salling Group, Denmark's largest retailer, Jysk, a worldwide retailer of household goods, Vestas, a global wind turbine manufacturer,[154] Terma A/S, a major defence and aerospace manufacturer, Per Aarsleff, a civil engineering company and several large retail companies.[11][155] Other large employers of note include Krifa, Systematic A/S,[156]), and Bestseller A/S. Since the early 2000s, the city has experienced an influx of larger companies moving from other parts of the Jutland peninsula.[157][158]

Port of Aarhus

The Port of Aarhus is one of the largest industrial ports in northern Europe with the largest container terminal in Denmark, processing more than 50% of Denmark's container traffic and accommodating the largest container vessels in the world.[159][160] It is a municipal self-governing port with independent finances. The facilities handle some 9.5 million tonnes of cargo a year (2012). Grain is the principal export, while feedstuffs, stone, cement and coal are among the chief imports.[161] Since 2012 the port has faced increasing competition from the Port of Hamburg and freight volumes have decreased somewhat from the peak in 2008.[160]

The ferry terminal presents the only alternative to the Great Belt Link for passenger transport between Jutland and Zealand. It has served different ferry companies since the first steamship route to Copenhagen opened in 1830. Currently, Mols-Linien operates the route and annually transports some two million passengers and a million vehicles. Additional roll-on/roll-off cargo ferries serve Finland and Kalundborg on a weekly basis and smaller outlying Danish ports at irregular intervals. Since the early 2000s the port has increasingly become a destination for cruise lines operating in the Baltic Sea.[162]

Tourism

The ARoS Art Museum, the Old Town Museum and Tivoli Friheden are among Denmark's top tourist attractions.[163] With a combined total of almost 1.4 million visitors they represent the driving force behind tourism but other venues such as Moesgård Museum and Kvindemuseet are also popular. The city's extensive shopping facilities are also said to be a major attraction for tourists, as are festivals, especially NorthSide and SPOT.[164][165] Many visitors arrive on cruise ships: in 2012, 18 vessels visited the port with over 38,000 passengers.[166]

In the 2010s, there was a significant expansion of tourist facilities, culminating in the opening of the 240-room Comwell Hotel in July 2014, which increased the number of hotel rooms in the city by 25%. Some estimates put the number of visitors spending at least one night as high as 750,000 a year, most of them Danes from other regions, with the remainder coming mainly from Norway, Sweden, northern Germany and the United Kingdom. Overall, they spend roughly DKK 3 billion (€402 million) in the city each year.[167] The primary motivation for tourists choosing Aarhus as a destination is experiencing the city and culture, family and couples vacation or as a part of a round trip in Denmark. The average stay is little more than three days on average.[167]

There are more than 30 tourist information spots across the city. Some of them are staffed, while others are online, publicly accessible touchscreens. The official tourist information service in Aarhus is organised under VisitAarhus, a corporate foundation initiated in 1994 by Aarhus Municipality and local commercial interest organisations.[168][169][170]

Research parks

The largest research park in Aarhus is INCUBA Science Park, focused on IT and biomedical research, It is based on Denmark's first research park, Forskerpark Aarhus (Research Park Aarhus), founded in 1986, which in 2007 merged with another research park to form INCUBA Science Park. The organisation is owned partly by Aarhus University and private investors and aims to foster close relationships between public institutions and startup companies.[171] It is physically divided across 4 locations after a new department was inaugurated in Navitas Park in 2015, which it will share with the Aarhus School of Marine and Technical Engineering and AU Engineering. Another major centre for knowledge is Agro Food Park in Skejby, established to facilitate co-operation between companies and public institutions working within food science and agriculture. In January 2017 Arla Foods will open the global innovation centre Arla Nativa in Agro Food Park and in 2018 Aarhus University is moving the Danish Centre for Food and Agriculture there as well.[172][173] In 2016, some 1000 people worked at Agro Food Park, spread across 50 companies and institutions and in August 2016 Agro Food Park management published plans to expand facilities from 92,000 m2 to 325,000 square metres (3,500,000 sq ft).[173]

In addition, Aarhus is home to the Aarhus School of Architecture, one of two Danish Ministry of Education institutions that provide degree programs in architecture, and some of the largest architecture firms in the Nordic countries such as Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects, Arkitema Architects and C. F. Møller Architects.[174] Taken together these organisations form a unique concentration of expertise and knowledge in architecture outside Copenhagen, which the Danish Ministry of Business and Growth refers to as arkitekturklyngen (the architecture cluster). To promote the "cluster", the School of Architecture will be given new school buildings centrally in the new Freight Station Neighborhood, planned for development in the 2020s. In the interim, the city council supports a culture, business and education centre in the area, which may continue in the future neighbourhood in some form. The future occupants of the neighbourhood will be businesses and organisations selected for their ability to be involved in the local community, and it is hoped that the area will evolve into a hotspot for creativity and design.[175][176][177]

Cityscape

Aarhus has developed in stages, from the Viking Age to modern times, all visible in the city today. Many architectural styles are represented in different parts of the city such as Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, National Romantic, Nordic Classicism, Neoclassical, Empire and Functionalism.[178] The city has developed around the main transport hubs – the river, the harbour, and later the railway station – and as a result, the oldest parts are also the most central and busiest today.[66]

The streets of Volden (The Rampart) and Graven (The Moat) testify to the defences of the initial Viking town, and Allégaderingen in Midtbyen roughly follows the boundaries of that settlement. The street network in the inner city formed during the Middle Ages with narrow, curved streets and low, dense housing by the river and the coast. Vesterport (Westward Gate) still bears the name of the medieval city gate and the narrow alleyways Posthussmøgen and Telefonsmøgen are remnants of toll stations from that time.[179] The inner city has the oldest preserved buildings, especially the Latin Quarter, with houses dating back to the early 17th century in Mejlgade and Skolegade.[35] Medieval merchants' mansions with courtyards can be seen in Klostergade, Studsgade and Skolegade. By far, the largest part of the present-day city was built during and after the industrialization of the late 1800s, and the most represented architectural styles today are historicism and modernism, especially the subgenre of Danish functionalism of which there are many fine examples.[180] The building boom of the 2000s has imprinted itself on Aarhus with a redeveloped harbourfront, many new neighbourhoods (also in the inner city), and a revitalized public space. It is also beginning to change the skyline with several dominating high-rises.[66]

Developments

In recent years, Aarhus has experienced a large demand in housing and offices, spurring a construction boom in some parts of the city. The newly built city district of Aarhus Ø, formerly docklands, includes major housing developments, mostly consisting of privately owned apartments, designed by architects such as CEBRA, and JDS Architects.[181][182]

In the second quarter of 2012, the population of the area stood at only 5; however, that number had risen to 3,940 by October 2019.[183]

The main public transportation service is bus line 23, as well as Østbanetorvet train station.[184] Plans to service the area by the light rail line Aarhus Letbane have now been shelved.[185]

Landmarks

Aarhus Cathedral (Århus Domkirke) in the centre of Aarhus, is the longest and tallest church in Denmark at 93 m (305 ft) and 96 m (315 ft) in length and height respectively. Originally built as a Romanesque basilica in the 13th century, it was rebuilt and enlarged as a Gothic cathedral in the late 15th and early 16th centuries.[186] Even though the cathedral stood finished around 1300, it took more than a century to build; the associated cathedral school of Aarhus Katedralskole was already founded in 1195 and ranks as the 44th oldest school in the world.[187] Another important and historic landmark in the inner city, is the Church of Our Lady (Vor Frue Kirke) also from the 13th century in Romanesque and Gothic style. It is smaller and less impressive, but it was the first cathedral of Aarhus and founded on an even older church constructed in 1060; the oldest stone church in Scandinavia.[188][189][190][191] Langelandsgade Kaserne in National Romantic Style from 1889 is the oldest former military barracks left in the country; home to the university Department of Aesthetics and Communication since 1989. [192][193][194] Marselisborg Palace (Marselisborg Slot), designed by Hack Kampmann in Neoclassical and Art Nouveau styles, was donated by the city to Prince Christian and Princess Alexandrine as a wedding present in 1898.[195][196] The Aarhus Custom House (Toldkammeret) from 1898, is said to be Hack Kampmann's finest work.[197]

Tivoli Friheden (Tivoli Freedom) opened in 1903 and has since been the largest amusement park in the city and a tourist attraction. Aarhus Theatre from 1916 in the Art Nouveau style is the largest provincial theatre in Denmark.[198][199] The early buildings of Aarhus University, especially the main building completed in 1932, designed by Kay Fisker, Povl Stegmann and by C.F. Møller have gained an international reputation for their contribution to functionalist architecture.[200] The City Hall (Aarhus Rådhus) from 1941 with an iconic 60 m (200 ft) tower clad in marble, was designed by Arne Jacobsen and Erik Møller in a modern Functionalist style.[201]

Culture

Aarhus is home to many annual cultural events and festivals, museums, theatres, and sports events of both national and international importance, and presents some of the largest cultural attractions in Denmark. There is a long tradition of music from all genres, and many Danish bands have emerged from Aarhus. Libraries, cultural centres and educational institutions present free or easy opportunities for the citizens to participate in, engage in, or be creative with cultural events and productions of all kinds.[202]

Since 1938, Aarhus has marketed itself as Smilets by (City of smiles) which has become both an informal moniker and official slogan. In 2011, the city council opted to change the slogan to "Aarhus. Danish for Progress" but it was unpopular and abandoned after just a few years.[203] Other slogans that have occasionally been used are Byen ved havet (City by the sea), Mellem bugt og bøgeskov (Between bay and beechwood) and Verdens mindste storby (World's smallest big city).[204][205] Aarhus is featured in popular songs such as Hjem til Aarhus by På Slaget 12, Lav sol over Aarhus by Gnags, 8000 Aarhus C by Flemming Jørgensen, Pigen ud af Aarhus by Tina Dickow and Slingrer ned ad Vestergade by Gnags. In 1919, the number Sangen til Aarhus (Song to Aarhus) had become a popular hit for a time, but the oldest and perhaps best known "national anthem" for the city is the classical Aarhus Tappenstreg from 1872 by Carl Christian Møller which is occasionally played at official events or at performances by local marching bands and orchestras.[206][207]

Museums

Aarhus has a range of museums, including two of the largest in the country, measured by the number of paying guests, Den Gamle By and ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum. Den Gamle By (The Old Town), officially Danmarks Købstadmuseum (Denmark's Market Town Museum), presents Danish townscapes from the 16th century to the 1970s with individual areas focused on different time periods. 75 historic buildings collected from different parts of the country have been brought here to create a small town in its own right.[208][209]

ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, the city's main art museum, is one of the largest art museums in Scandinavia with a collection covering Danish art from the 18th century to the present day as well as paintings, installations and sculptures representing international art movements and artists from all over the world. The iconic glass structure on the roof, Your Rainbow Panorama, was designed by Olafur Eliasson and features a promenade offering a colourful panorama of the city.[210][211]

The Moesgård Museum specialises in archaeology and ethnography in collaboration with Aarhus University with exhibits on Denmark's prehistory, including weapon sacrifices from Illerup Ådal and the Grauballe Man.[212] Kvindemuseet, the Women's Museum, from 1984 contains collections of the lives and works of women in Danish cultural history.[213] The Occupation Museum (Besættelsesmuseum) presents exhibits illustrating the German occupation of the city during the Second World War;[214] the University Park on the campus of Aarhus University includes the Natural History Museum with 5,000 species of animals, many in their natural surroundings;[215] and the Steno Museum is a museum of the history of science and medicine with a planetarium.[216] Kunsthal Aarhus (Aarhus Art Hall) hosts exhibitions of contemporary art including painting, sculpture, photography, performance art, film and video. Strictly speaking it is not a museum but an arts centre, one of the oldest in Europe, built and founded in 1917.[217]

Libraries and community centres

Public libraries in Denmark are also cultural and community centres. They play an active role in cultural life and host many events, exhibitions, discussion groups, workshops, educational courses and facilitate everyday cultural activities for and by the citizens. In June 2015, the large central library and cultural centre of Dokk1 opened at the harbour front. Dokk1 also includes civil administrations and services, commercial office rentals and a large underground robotic car park and aims to be a landmark for the city and a public meeting place. The building of Dokk1 and the associated squares and streetscape is also collectively known as Urban Mediaspace Aarhus and it is the largest construction project Aarhus municipality has yet undertaken.[218] Apart from this large main library, some neighbourhoods in Aarhus have a local library engaged in similar cultural and educational activities, but on a more local scale.[219]

The State Library (Statsbiblioteket) at the university campus has status of a national library.[220] The city is a member of the ICORN organisation (International Cities of Refuge Network) in an effort to provide a safe haven to authors and writers persecuted in their countries of origin.[221]

There are several cultural and community centres throughout the city. This includes Folkestedet in the central Åparken, facilitating events for and by non-commercial associations, organisations and clubs, and activities for the elderly, the nearby Godsbanen at the railway yard, with workshops, events and exhibitions, and Globus1 in Brabrand facilitating sports and various cultural activities.[222]

Performing arts

The city enjoys strong musical traditions, both classical and alternative, underground and popular, with educational and performance institutions such as the concert halls of Musikhuset, the opera of Den Jyske Opera, Aarhus Symfoniorkester (Aarhus Symphony Orchestra) and Det Jyske Musikkonservatorium (Royal Academy of Music, Aarhus/Aalborg). Musikhuset is the largest concert hall in Scandinavia, with seating for more than 3,600 people. Other major music venues include VoxHall, rebuilt in 1999, and the associated venue of Atlas, Train nightclub at the harbourfront, and Godsbanen, a former rail freight station.[223][224][225]

The acting scene in Aarhus is diverse, with many groups and venues engaged in a broad span of genres, from animation theatre and children's theatre to classical theatre and improvisational theatre. Aarhus Teater is the oldest and largest venue with mostly professional classical acting performances. Svalegangen, the second largest theatre, is more experimental with its performances and other notable groups and venues includes EntréScenen, Katapult, Gruppe 38, Helsingør Teater, Det Andet Teater and Teater Refleksion as well as dance venues like Bora Bora.[226][227][228] The cultural center of Godsbanen includes several scenes and stages[223] and the Concert Halls of Musikhuset also stage theatrical plays regularly and is home to the children's theatre Filuren and a comedy club.[229][230][231] The city hosts a biannual international theatre festival, International Living Theatre (ILT), with the next event being scheduled for 2021.[232]

Since 2010 the music production centre of PROMUS (Produktionscentret for Rytmisk Musik) has supported the rock scene in the city along with the publicly funded ROSA (Dansk Rock Samråd), which promotes Danish rock music in general.[233]

Aarhus is known for its musical history. Fuelled by a relatively young population jazz clubs sprang up in the 1950s which became a tour stop for many iconic American Jazz musicians. By the 1960s, the music scene diversified into rock and other genres and in the 1970s and 1980s, Aarhus became a centre for rock music, fostering iconic bands such as Kliché, TV-2 and Gnags and artists such as Thomas Helmig and Anne Linnet. Acclaimed bands since the 1970s include Under Byen, Michael Learns to Rock, Nephew, Carpark North, Spleen United, VETO, Hatesphere and Illdisposed in addition to individual performers such as Medina and Tina Dico.[234]

Events and festivals

Aarhus hosts many annual or recurring festivals, concerts and events, with the festival of Aarhus Festuge as the most popular and wide-ranging, along with large sports events.[235][236] Aarhus Festuge is the largest multicultural festival in Scandinavia, always based on a special theme and takes place every year for ten days between late August and early September, transforming the inner city with festive activities and decorations of all kinds.[237][238]

There are numerous music festivals; the eight-day Aarhus Jazz Festival features jazz in many venues across the city. It was founded in 1988 and usually takes place in July every year, occasionally August or September.[239] There are several annually recurring music festivals for contemporary popular music in Aarhus. NorthSide Festival presents well-known bands every year in mid-June on large outdoor scenes. It is a relatively new event, founded in 2010, but grew from a one-day event to a three-day festival in its first three years, now with 35,000 paying guests in 2015.[240][241] Spot festival is aiming to showcase up-and-coming Danish and Scandinavian talents at selected venues of the inner city.[242] The outdoor Grøn Koncert music festival takes place every year in many cities across Denmark, including Aarhus. Danmarks grimmeste festival (lit. Denmark's ugliest Festival) is a small summer music festival held in Skjoldhøjkilen, Brabrand.[243]

Aarhus also hosts recurring events dedicated to specific art genres. International Living Theatre (ILT) is a bi-annual festival, established in 2009, with performing arts and stage art on a broad scale. The festival has a vision of showing the best plays and stage art experiences of the world, while at the same time attracting thespians and stage art interested people from both Aarhus and Europe at large.[244] LiteratureXchange is a new annual festival from 2018, focused on literature from around the world as well as regional talents.[245] The city actively promotes its gay and lesbian community and celebrates the annual Aarhus Pride gay pride festival while Aarhus Festuge usually includes exhibits, concerts and events designed for the LGBT communities.[246]

Notable events of a local scope include the university boat-race, held in the University Park since 1991, which has become a local spectator event attracting some 20,000 people. The boat race pits costumed teams from the university departments against each other in inflatable boats in a challenge to win the Gyldne Bækken (Golden Chamber Pot) trophy.[247] The annual lighting of the Christmas lights on the Salling department store in Søndergade has also become an attraction in recent times, packing the pedestrianised city centre with thousands of revellers.[248] Significant dates such as Saint Lucy's Day, Sankt Hans (Saint John's Eve) and Fastelavn are traditionally celebrated with numerous events across the city.[249][250]

Parks, nature, and recreation

The beech forests of Riis Skov and Marselisborg occupy the hills along the coast to the north and south, and apart from the city centre, sandy beaches form the coastline of the entire municipality. There are two public sea baths, the northern Den Permanente below Riis Skov and close to the harbour area, and the southern Ballehage Beach in the Marselisborg Forests. As in most of Denmark, there are no private beaches in the municipality, but access to Den Permanente requires a membership, except in the summer.[251]

The relatively mild, temperate marine climate, allows for outdoor recreation year round, including walking, hiking, cycling, and outdoor team sports. Mountain biking is usually restricted to marked routes.[252] Watersports like sailing, kayaking, motor boating, etc. are also popular, and since the bay rarely freezes up in winter, they can also be practised most of the year. Recreational and transportational pathways for pedestrians and cyclists, radiate from the city centre to the countryside, providing safety from motorised vehicles and a more tranquil experience.[253][254] This includes the 19 kilometre long pathway of Brabrandstien, encircling the Brabrand Lake.[255][256] The long-range hiking route Aarhus-Silkeborg, starts off from Brabrandstien.[257]

Aarhus has an unusually high number of parks and green spaces, 134 of them, covering a total area of around 550 ha (1,400 acres).[258] The central Botanical Gardens (Botanisk Have) from 1875 are a popular destination, as they include The Old Town open-air museum and host a number of events throughout the year. Originally used to cultivate fruit trees and other useful plants for the local citizens, there are now a significant collection of trees and bushes from different habitats and regions of the world, including a section devoted to native Danish plants.[259] Recently renovated tropical and subtropical greenhouses, exhibit exotic plants from throughout the world.[260] Also in the city centre is the undulating University Park, recognised for its unique landscaped design with large old oak trees.[261] The Memorial Park (Mindeparken) at the coast below Marselisborg Palace, offers a panoramic view across the Bay of Aarhus and is popular with locals for outings, picnics or events.[262][263] Other notable parks include the small central City Hall Park (Rådhusparken) and Marienlyst Park (Marienlystparken).[264] Marienlyst Park is a relatively new park from 1988, situated in Hasle out of the inner city and is less crowded, but it is the largest park in Aarhus, including woodlands, large open grasslands and soccer fields.[265][266]

Marselisborg Forests and Riis Skov, has a long history of recreational activities of all kinds, including several restaurants, hotels and opportunities for green exercise. There are marked routes here for jogging, running and mountain biking and large events are hosted regularly. This includes running events, cycle racing and orienteering, the annual Classic Race Aarhus with historic racing cars, all attracting thousands of people.[267] Marselisborg Deer Park (Marselisborg Dyrehave) in Marselisborg Forests, comprises 22 ha (54 acres) of fenced woodland pastures with free-roaming sika and roe deer.[268] Below the Moesgård Museum in the southern parts of the Marselisborg Forests, is a large historical landscape of pastures and woodlands, presenting different eras of Denmark's prehistory. Sections of the forest comprise trees and vegetation representing specific climatic epochs from the last Ice Age to the present.[269] Dotted across the landscape are reconstructed Stone Age and Bronze Age graves, buildings from the Iron Age, Viking Age and medieval times, with grazing goats, sheep and horses in between.[270]

Food, drink, and nightlife

Aarhus has a large variety of restaurants and eateries offering food from cultures all over the world, especially Mediterranean and Asian, but also international gourmet cuisine, traditional Danish food and New Nordic Cuisine.[271] Among the oldest restaurants are Rådhuscafeen (lit. The City Hall Café), opened in 1924, serving a menu of traditional Danish meals, and Peter Gift from 1906, a tavern with a broad beer selection and a menu of smørrebrød and other Danish dishes.[272][273] In Aarhus, New Nordic can be experienced at Kähler Villa Dining, Hærværk and Domestic, but local produce can be had at many places, especially at the twice-weekly food markets in Frederiksbjerg.[274] Aarhus and Central Denmark Region was selected as European Region of Gastronomy in 2017.[275][276] The city (and municipality) is a member of the Délice Network, an international non-profit organization nurturing and facilitating knowledge exchange in gastronomy.[277]

Appraised high-end restaurants serving international gourmet cuisine include Frederikshøj, Substans, Gastromé, Det Glade Vanvid, Nordisk Spisehus, Restaurant Varna, Restaurant ET, Gäst, Brasserie Belli, Møf.[278][279][280][281] Restaurants in Aarhus were the first in provincial Denmark to receive Michelin stars since 2015, when Michelin inspectors ventured outside Copenhagen for the first time.[282]

Vendors of street food are numerous throughout the centre, often selling from small trailers on permanent locations formally known as Pølsevogne (lit. sausage wagons), traditionally serving a Danish variety of hot dogs, sausages and other fast food. There are increasingly more outlets inspired by other cultural flavours such as sushi, kebab and currywurst.[283][284]

The city centre is packed with cafés, especially along the river and the Latin quarter. Some of them also include an evening restaurant, such as Café Casablanca, Café Carlton, Café Cross and Gyngen.[285] Aarhus Street Food and Aarhus Central Food Market are two indoor food courts from 2016 in the city centre, comprising a variety of street food restaurants, cafés and bars.[286][287]

Aarhus has a robust and diverse nightlife. The action tends to concentrate in the inner city, with the pedestrianised riverside, Frederiksgade, the Latin Quarter, and Jægergårdsgade on Frederiksbjerg as the most active centres at night, but things are stirring elsewhere around the city too. The nightlife scene offers everything from small joints with cheap alcohol and a homely atmosphere to fashionable nightclubs serving champagne and cocktails or small and large music venues with bars, dance floors and lounges. A short selection of well-established places where you can have a drink and socialise, include the fashionable lounge and night club Kupé at the harbourfront, the relaxed Ris Ras Filliongongong offering waterpipes and an award-winning beer selection, Fatter Eskild with a broad selection of Danish bands playing mostly blues and rock, the wine and book café Løve's in Nørregade, Sherlock Holmes, a British-style pub with live music, and the brew pub of Sct. Clemens, with A Hereford Beefstouw restaurant across the cathedral.[288][289][290] A few nightlife spots are aimed at gays and lesbians specifically, including Gbar (nightclub) and Café Sappho.[291]

The Århus Set (Danish: Århus Sæt) is a set of drinks often ordered together, named for the city and consisting of two beverages, one Ceres Top beer and one shot Arnbitter, both originally from Aarhus. Ordering "a set" suffices in most bars and pubs.[292][293] Aarhus Bryghus is a local craft brewery with a sizeable production. The brewery is located in the southern district of Viby and a large variety of their craft brews are available there, in most larger well-assorted stores in the city, and in some bars and restaurants as well. They also export.[294]

Local dialect

The Aarhus dialect, commonly called Aarhusiansk (Aarhusian in English), is a Jutlandic dialect in the Mid-Eastern Jutland dialect area, traditionally spoken in and around Aarhus.[295] Aarhusian, as with most local dialects in Denmark, has diminished in use through the 20th century and most Danes today speak some version of Standard Danish with slight regional features. Aarhusian, however, still has a strong presence in older segments of the population and in areas with high numbers of immigrants.[296][297][298] Some examples of common, traditional and unique Aarhusian words are: træls ('tiresome'), noller ('silly' or 'dumb') and dælme (excl. 'damn me!').[299][300] The dialect is notable for single-syllable words ending in "d" being pronounced with stød while the same letter in multiple-syllable words is pronounced as "j", i.e., Odder is pronounced "Ojjer". Like other dialects in East Jutland, it has two grammatical genders, similar to Standard Danish, but different from West Jutlandic dialects, which have only one.[301] In 2009, the University of Aarhus compiled a list of contemporary public figures who best exemplify the dialect, including Jacob Haugaard, Thomas Helmig, Steffen Brandt, Stig Tøfting, Flemming Jørgensen, Tina Dickow and Camilla Martin. In popular culture, the dialect features prominently in Niels Malmros's movie Aarhus by Night and in 90s comedy sketches by Jacob Haugaard and Finn Nørbygaard.[302]

Sports

| Club | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Founded | Titles | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aarhus Gymnastikforening | Football | Superliga | Ceres Park (20,032) | 1880 | 5 | 23,990[303] |

| Aarhus GF Håndbold | Handball | Danish Handball League | Ceres Arena (4,700) | 2001 | 9[304] | 4,700[305] |

| Bakken Bears | Basketball | Danish Basketball League | Vejlby-Risskov Hallen (1,800) | 1962 | 16 | 2,500[306] |

Aarhus has three major men's professional sports teams: the Superliga team Aarhus Gymnastikforening (AGF), Danish Handball League's Aarhus GF Håndbold, and Danish Basketball League's Bakken Bears. Notable or historic clubs include Aarhus 1900, Aarhus Fremad, Idrætsklubben Skovbakken and Aarhus Sejlklub. Aarhus Idrætspark has hosted matches in the premiere Danish soccer league since it was formed in 1920 and matches for the national men's soccer team in 2006 and 2007.[307] The five sailing clubs routinely win national and international titles in a range of disciplines and the future national watersports stadium will be located on the Aarhus Docklands in the city centre.[308][309] The Bakken Bears won the Danish basketball championships in 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014.[310]

The municipality actively supports sports organisations in and around the city, providing public organisations that aim to attract major sporting events and strengthen professional sports.[311] The National Olympic Committee and Sports Confederation of Denmark counts some 380 sports organisations within the municipality and about one third of the population are members of one.[312] Soccer is by far the most popular sport followed by Gymnastics, Handball and Badminton.[312]

In recent decades, many free and public sports facilities have sprung up across the city, such as street football, basketball, climbing walls, skateboarding and beach volley. Several natural sites also offer green exercise, with exercise equipment installed along the paths and tracks reserved for mountain biking. The newly reconstructed area of Skjoldhøjkilen is a prime example.[313]

Aarhus has hosted many sporting events including the 2010 European Women's Handball Championship, the 2014 European Men's Handball Championship, the 2013 Men's European Volleyball Championships, the 2005 European Table Tennis Championships, the Denmark Open in badminton, the UCI Women's Road Cycling World Cup, the 2006 World Orienteering Championships, the 2006 World Artistic Gymnastics Championships and the GF World Cup (women's handball).[314] On average, Aarhus is hosting one or two international sailing competitions every year. In 2008, the city hosted the ISAF Youth Sailing World Championships[315][316] and in 2018 it was host to the ISAF Sailing World Championships, the world championship for the 12 Olympic sailing disciplines.[317] Aarhus is an important qualifier for the 2020 Olympics.[318]

Education

Aarhus is the principal centre for education in the Jutland region. It draws students from a large area, especially from the western and southern parts of the peninsula. The relatively large influx of young people and students creates a natural base for cultural activities.[319] Aarhus has the greatest concentration of students in Denmark, fully 12% of citizens attending short, medium or long courses of study. In addition to around 25 institutions of higher education, several research forums have evolved to assist in the transfer of expertise from education to business.[320] The city is home to more than 52,000 students.[321][when?]

Since 2012, Aarhus University (AU) has been the largest university in Denmark by number of students enrolled.[322] It is ranked among the top 100 universities in the world by several of the most influential and respected rankings. The university has approximately 41,500 Bachelor and Master students enrolled as well as about 1,500 PhD students.[322] It is possible to engage in higher academic studies in many areas, from the traditional spheres of natural science, humanities and theology to more vocational academic areas like engineering and dentistry.[323]

Aarhus Tech is one of the largest technical colleges in Denmark, teaching undergraduate study programmes in English, including vocational education and training (VET), continuing vocational training (CVT), and human resource development.[324] Business Academy Aarhus is among the largest business academies in Denmark and offers undergraduate and some academic degrees, in IT, business and technical fields. The academic level technical aspects are covered in a collaboration with Aarhus Tech, Aarhus School of Marine and Technical Engineering and Aarhus Educational Centre for Agriculture.[325] The Danish School of Media and Journalism (DMJX) is the oldest and largest of the colleges, offering journalism courses since 1946, with approximately 1,700 students as of 2014. DMJX has been an independent institution since 1974, conducting research and teaching at undergraduate level, and in 2004, master's courses in journalism was established in a collaboration with Aarhus University. The latter is offered through the Centre for University studies in journalism, granting degrees through the university.[326]

The Royal Academy of Music in Aarhus (Det Jyske Musikkonservatorium) is a conservatoire, established under the auspices of the Danish Ministry of Culture in 1927. In 2010, it merged administratively with the Royal Academy of Music in Aalborg, which was founded in 1930.[327] Under the patronage of His Royal Highness Crown Prince Frederik, it offers graduate level studies in areas such as music teaching, and solo and professional musicianship. VIA University College was established in January 2008 and is one of eight new regional organisations offering bachelor courses of all kinds, throughout the Central Denmark Region. It offers over 50 higher educations, taught in Danish or sometimes in English, with vocational education and it participates in various research and development projects.[328] Aarhus School of Architecture (Arkitektskolen Aarhus) was founded in 1965. Along with the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts of Copenhagen, it is responsible for the education of architects in Denmark. With an enrolment of approximately 900 students, it teaches in five main departments: architecture and aesthetics, urban and landscape, architectonic heritage, design and architectural design.[329]

Transport

Aarhus has two ring roads; Ring 1, roughly encircling the central district of Aarhus C, and the outlying Ring 2. Six major intercity motorways radiate from the city centre, connecting with nearby cities Grenå, Randers, Viborg, Silkeborg, Skanderborg and Odder.[330]

In the inner city, motorised traffic is highly regulated, larger parts are pedestrianised and in the 2000s, a system of roads prioritised for cyclists have been implemented, connecting to suburban areas.[331]

The main railway station in Aarhus is Aarhus Central Station located in the city centre. DSB has connections to destinations throughout Denmark and also services to Flensburg and Hamburg in Germany.[332]

Aarhus Letbane is a local electric tram-train system that opened in December 2017, connecting the central station and the inner city with the University Hospital in Skejby and also replaced local railway services to Grenaa and Odder in late 2018. It is the first electric light rail system in Denmark and more routes are planned to open in coming years. Tickets for the light rail are also available in local yellow bus lines.[333]

Most city bus lines go through the inner city and pass through either Park Allé or Banegårdspladsen, or both, right at the central station.[334] Regional and Inter-city buses terminate at Aarhus Bus Terminal, just east of the central station.[335][336] FlixBus provides long-distance buses that travel to other cities in Denmark and Europe.[337]

Ferries administered by Danish ferry company Mols-Linien transports passengers and motorvehicles between Aarhus and Sjællands Odde on Zealand.[338] The ferries comprises HSC KatExpress 1 and HSC KatExpress 2, the world's largest diesel-powered catamarans,[339] and HSC Max Mols. [340]

Aarhus Airport is located on Djursland, 40 km (25 mi) north-east of Aarhus near Tirstrup, and provides links to both Copenhagen and international destinations.[341] The larger Billund Airport is situated 95 km (59 mi) south-west of Aarhus.[342] There has been much discussion about constructing a new airport closer to the city for many years, but so far no plans have been realised.[343] In August 2014, the city council officially initiated a process to assert the viability of a new international airport.[344][345] A small seaplane now operates four flights daily between Aarhus harbour and Copenhagen harbour.[346]

Aarhus has a free bike sharing system, Aarhus Bycykler (Aarhus City Bikes). The bicycles are available from 1 April to 30 October at 57 stands throughout the city and can be obtained by placing a DKK 20 coin in a release slot, like caddies in a supermarket. The coin can be retrieved when the bike is returned at a random stand. Bicycles can also be hired from many shops.[347]

Healthcare

Aarhus is home to Aarhus University Hospital, one of six Danish "Super Hospitals" officially established in 2007 when the regions reformed the Danish healthcare sector.[348] The university hospital is the result of a series of mergers in the 2000s between the local hospitals of Skejby Sygehus, the Municipal Hospital, the County Hospital, Marselisborg Hospital and Risskov Psychiatric Hospital. It is today the largest hospital in Denmark with a combined staff of some 10,000 and 1,150 patient beds,[349] and has been ranked the best hospital in Denmark consecutively since 2008.[350] In 2012, construction of a new large hospital building began, known as Det Nye Universitetshospital (DNU) or 'The New University Hospital' in English, and it is centralising and accommodating all of the former departments, ending in 2019. The new hospital is divided in four clinical centres, a service centre and one administrative unit along with twelve research centres.[351][352]

Private hospitals specialised in different areas from plastic surgery to fertility treatments operate in Aarhus as well. Ciconia Aarhus Private Hospital founded in 1984 is a leading Danish fertility clinic and the first of its kind in Denmark. Ciconia has provided for the birth of 6,000 children by artificial insemination and continually conducts research into the field of fertility.[353] Aagaard Clinic, established in 2004, is another private fertility and gynaecology clinic which since 2004 has undertaken fertility treatments that has resulted in 1550 births.[354] Aarhus Municipality also offers a number of specialised services in the areas of nutrition, exercise, sex, smoking and drinking, activities for the elderly, health courses and lifestyle.[355]

Media