Arawak (Arowak, Aruák), also known as Lokono (Lokono Dian, literally "people's talk" by its speakers), is an Arawakan language spoken by the Lokono (Arawak) people of South America in eastern Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana.[2] It is the eponymous language of the Arawakan language family.

| Arawak | |

|---|---|

| Lokono | |

| Native to | French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, Venezuela, Jamaica, Barbados |

| Region | Guianas |

| Ethnicity | Lokono (Arawak) |

Native speakers | (2,500 cited 1990–2012)[1] |

Arawakan

| |

| Latin script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | arw |

| ISO 639-3 | arw |

| Glottolog | araw1276 |

| ELP | Lokono |

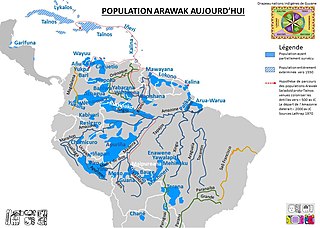

Arawakan languages in South America and the Caribbean | |

Arawak is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Lokono is an active–stative language.[3]

History

editLokono is a critically endangered language.[4] The Lokono language is most commonly spoken in South America. Some specific countries where this language is spoken include Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, and Venezuela.[5] The percentage of living fluent speakers with active knowledge of the language is estimated to be 5% of the ethnic population.[6] There are small communities of semi-speakers who have varying degrees of comprehension and fluency in Lokono that keep the language alive.[7] It is estimated that there are around 2,500 remaining speakers (including fluent and semi-fluent speakers).[8] The decline in the use of Lokono as a language of communication is due to its lack of transmission from older speakers to the next generation. The language is not being passed to young children, as they are taught to speak the official languages of their countries.[4]

Classification

editThe Lokono language is part of the larger Arawakan language family spoken by indigenous people in South and Central America along with the Caribbean.[9] The family spans four countries of Central America — Belize, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua — and eight of South America — Bolivia, Guyana, French Guiana, Surinam, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Brazil (and also formerly Argentina and Paraguay). With about 40 extant languages, it is the largest language family in Latin America.[10]

Etymology

editArawak is a tribal name in reference to the main crop food, the cassava root, commonly known as manioc. The cassava root is a popular staple for millions of people in South America, Asia and Africa.[11] It is a woody shrub grown in tropical or subtropical regions. Speakers of Arawak also identify themselves as Lokono, which translates as "the people". They call their language Lokono Dian, "the people's speech".[12]

Alternative names of the same language include Arawák, Arahuaco, Aruak, Arowak, Arawac, Araguaco, Aruaqui, Arwuak, Arrowukas, Arahuacos, Locono, and Luccumi.[13]

Geographic distribution

editLokono is an Arawakan language most commonly found to be spoken in eastern Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana. It was also formerly spoken on Caribbean islands such as Barbados and other neighboring countries. There are approximately 2,500 native speakers today. The following are regions where Arawak has been found spoken by native speakers.[1]

Phonology

editConsonants

edit| Bilabial | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | t | k | ||||

| aspirated | tʰ | kʰ | |||||

| voiced | b | d | |||||

| Fricative | ɸ | s | h | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | ||||

| Rhotic | trill | r | |||||

| tap | ɽ | ||||||

William Pet observes an additional /p/ in loanwords.[15]

| Character Used | Additional Usage | IPA symbol | Arawak Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| b | b | Like b in boy. | |

| č | ch, tj | t͡ʃ | Like ch in chair. |

| d | d ~ d͡ʒ | Like d in day. Before i the Arawak pronunciation sounds like the j in jeep. | |

| f | ɸ | This sound does not exist in English. It is pronounced by narrowing your lips and blowing through them, as if you were playing a flute. | |

| h | x | h | Like h in hay. |

| j | y | j | Like y in yes. |

| k | c, qu | k | Like the soft k sound in English ski. |

| kh | k, c, qu | kʰ | Like the hard k sound in English key. |

| l | l | Like l in light. | |

| lh | ř | ɽ | No exact equivalent in American English. This is a retroflex r, pronounced with the tongue touching the back of the palate. It is found in Indian-English. Some English speakers also pronounce this sound in the middle of the word "better" or "party". |

| m | m | Like m in moon. | |

| n | n | Like n in night. | |

| p | p | Like the soft p in spin. | |

| r | ɾ | Like the r in Spanish pero, somewhat like the tt in American English "better". | |

| s | z, c | s | Like the s in sun. |

| t | t ~ t͡ʃ | Like the soft t in star. Before i the Arawak pronunciation sounds like the ch in cheek. | |

| th | t | tʰ ~ t͡ʃʰ | Like the hard t in tar. Before i the Arawak pronunciation sounds like the ch in cheek. |

| hu | w | w | w as in way. |

| ' | ʔ | A glottal stop, like the pause in the word uh-oh. |

Vowels

edit| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɨ | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

Pet notes that phonetic realization of /o/ varies between [o] and [u].[15]

| Character Used | Additional Usage | IPA Symbol | Arawak Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | a | Like the a in father. | |

| aa | a· | aː | Like a only held longer. |

| e | e | Like the e sound in Spanish, similar to the a in gate. | |

| ee | e·, e: | eː | Like e only held longer. |

| i | i | Like the i in police. | |

| ii | i·, i: | iː | Like i only held longer. |

| o | o ~ u | Like o in note or u in flute. | |

| oo | o·, o: | oː | Like o only held longer. |

| y | u, |

ɨ | Like the e in roses. |

| yy | y:, uu, |

ɨː | Like the above y, only held longer. |

Grammar

editThe personal pronouns are shown below. The forms on the left are free forms, which can stand alone. The forms on the right are bound forms (prefixes), which must be attached to the front of a verb, a noun, or a postposition.[16]

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Person | de, da- | we, wa- |

| 2nd Person | bi, by- | hi, hy- |

| 3rd Person | li, ly- (he)

tho, thy- (she) |

ne, na- |

Cross-referencing affixes

editAll verbs are sectioned into transitive, active transitive, and stative intransitive.[14]

| prefixes | suffixes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | plural | singular | plural | ||

| 1st person | nu- or ta- | wa- | -na, -te | -wa | |

| 2nd person | (p)i- | (h)i- | -pi | -hi | |

| 3rd person | non-formal | ri-, i | na- | ri, -i | -na |

| formal | thu-, ru- | na- | -thu,-ru, -u | -na | |

| 'impersonal' | pa- | - | - | - | |

A= Sa=cross referencing prefix

O=So= cross referencing suffix

Vocabulary

editGender

editIn the Arawak language, there are two distinct genders of masculine and feminine. They are used in cross-referencing affixes, in demonstratives, in nominalization and in personal pronouns. Typical pronominal genders, for example, are feminine and non-feminine. The markers go back to Arawak third-person singular cross-referencing: feminine -(r)u, masculine -(r)i[13]

Number

editArawak Languages do distinguish singular and plural, however plural is optional unless the referent is a person. Markers used are *-na/-ni (animate/human plural) and *-pe (inanimate/animate non-human plural).[13]

Possession

editArawak nouns are fragmented into inalienably and alienably possessed. Inalienably crossed nouns include things such as body parts, terms for kinship and common nouns like food selections. Deverbal nominalization belong to that grouping. Both forms of possession are marked with prefixes (A/Sa). Inalienably possessed nouns have what is known as an "unpossessed" form (also known as "absolute") marked with the suffix *-tfi or *-hV. Alienably possessed nouns take one of the suffixes *-ne/ni, *-te, *-re, *i/e, or *-na. All suffixes used as nominalizers.[17]

Negation

editArawak languages have a negative prefix ma- and attributive-relative prefix ka-. An example of the use is ka-witi-w ("a woman with good eyes") and ma-witti-w ("a woman with bad eyes", i.e., a blind woman).

Tenses

editTenses are added at the end of a sentence: past tense is indicated with bura or bora (from ubura "before"), future tense with dikki (from adiki "after"), present continuous tense uses loko or roko.[18][19][further explanation needed]

Writing system

editThe Arawak language system has an alphabetical system similar to the Roman Alphabet with some minor changes and new additions to letters.

| Character Used | Additional Usage | IPA symbol | Arawak Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| b | b | Like b in boy. | |

| č | tj | t͡ʃ | Like ch in chair. |

| d | d ~ d͡ʒ | Like d in day. Before i the Arawak pronunciation sounds like the j in jeep. | |

| f | ɸ | This sound does not exist in English. It is pronounced by narrowing your lips and blowing through them, as if you were playing a flute. | |

| x | h | h | Like h in hay. |

| j | j | Like y in yes. | |

| k | c, qu | k | Like the soft k sound in English ski. |

| kh | k, c, qu | kh | Like the hard k sound in English key. |

| l | l | Like l in light. | |

| ř | rh, lh | ɽ | No exact equivalent in American English. This is a retroflex r, pronounced with the tongue touching the back of the palate. It is found in Indian-English. Some American English speakers also pronounce this sound in the middle of the word "hurting." |

| m | m | Like m in moon. | |

| n | n | Like n in night. | |

| p | p | Like the soft p in spin. | |

| r | ɾ | Like the r in Spanish pero, somewhat like the tt in American English butter. | |

| s | z, c | s | Like the s in sun. |

| t | t ~ t͡ʃ | Like the soft t in star. Before i the Arawak pronunciation sounds like the ch in cheek. | |

| th | t | th ~ t͡ʃʰ | Like the hard t in tar. Before i the Arawak pronunciation sounds like the ch in cheek. |

| hu | w | w | Like w in way. |

| ' | ʔ | A pause sound (glottal stop), like the one in the middle of the word "uh-oh." |

| Character Used | Additional Usage | IPA Symbol | Arawak Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | a | Like the a in father. | |

| aa | a· | aː | Like a only held longer. |

| e | e | Like the e sound in Spanish, similar to the a in gate. | |

| ee | e·, e: | eː | Like e only held longer. |

| i | i | Like the i in police. | |

| ii | i·, i: | iː | Like i only held longer. |

| o | o ~ u | Like o in note or u in flute. | |

| oo | o·, o: | oː | Like o only held longer. |

| y | ɨ | Like the u in upon, only pronounced higher in the mouth. | |

| yy | y: | ɨː | Like y only held longer. |

The letters in brackets under each alphabetical letter is the IPA symbol for each letter.[1]

Examples

edit| English | Eastern Arawak (French Guiana) | Western Arawak (Venezuela, Guyana, and Suriname) |

|---|---|---|

| One | Ábą | Aba |

| Two | Bian | Biama |

| Three | Kabun | Kabyn |

| Four | Biti | Bithi |

| Man | Wadili | Wadili |

| Woman | Hiaro | Hiaro |

| Dog | Péero | Péero |

| Sun | Hadali | Hadali |

| Moon | Kati | Kathi |

| Water | Uini | Vuniabu |

References

edit- ^ a b c Arawak at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ Pet 2011, p. 2

- ^ Aikhenvald, "Arawak", in Dixon & Aikhenvald, eds., The Amazonian Languages, 1999.

- ^ a b "Lokono". Endangered Languages Project. Archived from the original on 2018-01-06. Retrieved 2018-01-05.

- ^ Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. (2006). "7. Areal Diffusion, Genetic Inheritance and Problems of Subgrouping: A north Arawak Case Study". In Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y.; Dixon, R. M. W. (eds.). Areal Diffusion and Genetic Inheritance: Problems in Comparative Linguistics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199283088. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Edwards, W.; Gibson, K. (1979). "An Ethnohistory of Amerindians in Guyana". Ethnohistory. 26 (2): 161. doi:10.2307/481091. JSTOR 481091.

- ^ Harbert, Wayne; Pet, Willem (1988). "Movement and Adjunct Morphology in Arawak and Other Languages". International Journal of American Linguistics. 54 (4): 416–435. doi:10.1086/466095. S2CID 144291701.

- ^ Aikhenvald, Alexandra (2013). "Arawak Languages". Linguistics. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199772810-0119. ISBN 9780199772810. Archived from the original on 2018-01-06. Retrieved 2018-01-05 – via Oxford Bibliographies.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ De Carvalho, Fernando O. (2016). "The diachrony of person-number marking in the Lokono-Wayuunaiki subgroup of the Arawak family: reconstruction, sound change and analogy". Language Sciences. 55: 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2016.02.001.

- ^ "Arawak languages". Research@JCU. Archived from the original on 2016-08-28. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ^ Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. (1995). "Person marking and discourse in North Arawak languages". Studia Linguistica. 49 (2): 152–195. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9582.1995.tb00469.x.

- ^ A Brief Introduction to Some Aspects of the Culture and Language of the Guyana Arawak (Lokono) Tribe. Amerindian Languages Project, University of Guyana. 1980. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ a b c Hill, Johnathon (2010-10-01). Comparative Arawakan Histories : Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252091506. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ a b Pet 2011

- ^ a b Pet, William (1988). Lokono dian: the Arawak language of Surinam: a sketch of its grammatical structure and lexicon (PhD thesis). Cornell University.

- ^ Pet 2011, p. 12

- ^ Rybka, Konrad (2015). "State-of-the-Art in the Development of the Lokono Language". Language Documentation & Conservation. 9: 110–133. hdl:10125/24635.

- ^ Brinton, Daniel Garrison (1871). "The Arawack language of Guiana in its linguistic and ethnological relations". Philadelphia, McCalla & Stavely.

- ^ Patte, Marie-France (2011). La langue arawak de Guyane: présentation historique et dictionnaires arawak-français et français-arawak (PDF) (in French). Marseille: Institut de recherche pour le développement. ISBN 978-2-7099-1715-5.

- ^ Trevino, David (2016). "Arawak". Salem Press Encyclopedia – via ebescohost.

Bibliography

edit- Pet, Willem J. A. (2011). A Grammar Sketch and Lexicon of Arawak (Lokono Dian) (PDF). SIL eBook 30. SIL International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-13. Retrieved 2014-10-24.