Assisted suicide describes the process by which a person, with the help of others, takes medications to die by suicide.[1] It was formerly referred to as physician-assisted suicide (PAS), but is now more commonly referred to as medical aid in dying.[2]

This medical practice is an end-of-life measure for a person suffering a painful, terminal illness.[3] Once it is determined that the person's situation qualifies under the laws for that location, the physician's assistance is usually limited to writing a prescription for a lethal dose of drugs. Voluntary euthanasia, meanwhile, is a related but distinct practice where the doctor has a more active role (euthanasia). Both fall under the concept of the right to die.

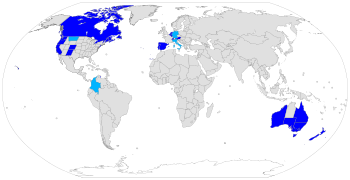

Medical aid in dying is legal in some countries, under certain circumstances, including Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, parts of the United States and five out of six states in Australia. The constitutional courts of Colombia, Germany and Italy have legalized assisted suicide, but their governments have not yet legislated or regulated the practice. In most of those states or countries, to qualify for legal assistance, individuals who seek a physician-assisted suicide must meet certain criteria, including: they are of sound mind, voluntarily and repeatedly express their wish to die, and take the specified, lethal dose by their own hand. The laws vary in scope from place to place. In the United States, medical aid in dying is limited to those who have a prognosis of six months or less to live; in this sense, it is a similar qualification to being put on hospice. In other countries, such as Germany, Canada, Switzerland, Spain, Italy, Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands, a terminal diagnosis is not a requirement, and voluntary euthanasia is additionally allowed.

In some countries and jurisdictions, helping a person kill themself is illegal.[4] People who support legalizing medical aid in dying want the people who assist in a voluntary death to be exempt from criminal prosecution for manslaughter or similar crimes.

Terminology

editAssisted suicide, physician-assisted suicide or medical aid in dying, involves a physician "knowingly and intentionally providing a person with the knowledge or means or both required to commit suicide, including counseling about lethal doses of drugs, prescribing such lethal doses or supplying the drugs". This is a regulated practice in which the patient must meet very strict criteria in order to receive medical assistance in dying.[5][6][7]

Euthanasia, sometimes referred to as mercy killing, is where the person dying does not directly bring about their own death, but is killed in order to stop the person from experiencing further suffering. Euthanasia can occur with or without consent, and can be classified as voluntary, non-voluntary or involuntary. Killing a person who is suffering and who consents is called voluntary euthanasia. This is currently legal in some regions.[8] If the person is unable to provide consent it is referred to as non-voluntary euthanasia. Killing a person who does not want to die, or who is capable of giving consent and whose consent has not been solicited, is the crime of involuntary euthanasia, and is regarded as murder.

Assisted dying includes both assisted suicide and euthanasia.

Other terms

editRight to die is the belief that people have a right to die, either through various forms of suicide, euthanasia, or refusing life-saving medical treatment.

Suicidism is currently used in two meanings;

- "the quality or state of being suicidal"[9]

- negative attitudes of society towards suicide, which can lead to suicidal people experiencing discrimination, stigmatization, exclusion, pathologization, and incarceration. They may be hospitalized and/or drugged without their consent, and have difficulties in finding jobs or housing, and have their parental rights revoked. Suicide is not seen as a positive human right, and/or a logical decision given circumstances. Suicidal people are not seen as having potentially valuable messages to convey.[10][11][12]

Concerns about use of the term "assisted suicide"

editSome advocates for assisted suicide strongly oppose the use of "assisted suicide" and "suicide" when referring to physician-assisted suicide, and prefer phrases like "medical aid in dying" (MAiD) or "assisted dying." The motivation for this is to distance the debate from the suicides commonly performed by those not terminally ill and not eligible for assistance where it is legal. They feel those cases have negatively impacted the word "suicide" to the point that it should not be used to refer to the practice of a physician prescribing lethal drugs to a person with a terminal illness.[13][14] However, in certain jurisdictions, like Canada, "aid in dying" does not require a person's natural death to be reasonably foreseeable in order to be eligible for MAiD. Moreover, the term "assisted dying" is also used to refer to other practices like voluntary euthanasia and terminal sedation.[15][16]

In November 2022, after deliberation at its biannual Annual General Meeting, the World Federation of Right to Die Societies discussed and adopted as the preferred term "voluntary assisted dying" in consideration of a range of aspects regarding suicidism.

Arguments for and against medical aid in dying

editArguments for

editArguments in support of assisted death include

- respect for patient autonomy

- personal liberty

- compassion

- equal treatment of terminally ill patients on and off life support

- transparency[17] and

- ethics of responsibility.[18]

Reasons given by people for seeking medical aid in dying

editIn 2022 in the Oregon program, the most frequently reported end-of-life concerns were

- decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable (89%)

- loss of autonomy (86%)

- loss of dignity (62%)

- burden on family/caregivers (46%)

- losing control of bodily functions (44%)

- inadequate pain control, or concern about it (31%)

- financial implications of treatment (6%).[19]

Previous years had seen similar factors.[20]

Pain has mostly not been reported as the primary motivation for seeking medical aid in dying in the United States.[21]

Arguments against

editArguments against assisted suicide are

- lack of genuine consent. Some are concerned that vulnerable populations may be at risk of untimely deaths because "patients might be subjected to medical aid in dying without their genuine consent".[22]

- risk of facilitating increase in suicide due to non-medical factors. A 1996 survey of Oregon emergency physicians concerning the Oregon initiative found that 83% agreed that patients "Might feel pressure because of burden to others" and 70% agreed that patients "Might feel pressure because of financial concerns".[23]

- slippery slope. This concern is that once medical aid in dying is initiated for the terminally ill it will progress to other vulnerable communities, namely disabled people, and may begin to be used by those who feel less worthy based on their demographic or socioeconomic status.[22][24] The UK Government Health and Social Care Select Committee found no evidence of the ‘slippery slope’ having occurred when it examined the global assisted suicide situation in 2024.[25]

Opinions on medical aid in dying

editMedical ethics

editHippocratic Oath

editSome doctors[26] state that physician-assisted suicide is contrary to the Hippocratic Oath (c. 400 BC), which is the oath historically taken by physicians. It states "I will give no deadly medicine to any one if asked, nor suggest any such counsel".[27][28] The original oath however has been modified many times and, contrary to popular belief, is not required by most modern medical schools, nor confers any legal obligations on individuals who choose to take it.[29] There are also procedures forbidden by the Hippocratic Oath that are in common practice today, such as abortion and execution.[30]

Declaration of Geneva

editThe Declaration of Geneva is a revision of the Hippocratic Oath, first drafted in 1948 by the World Medical Association in response to forced (involuntary) euthanasia, eugenics and other medical crimes performed in Nazi Germany. It contains, "I will respect the autonomy and dignity of my patient," as well as "I will maintain the utmost respect for human life."[31]

International Code of Medical Ethics

editThe International Code of Medical Ethics, last revised in 2006, includes "A physician shall always bear in mind the obligation to respect human life" in the section "Duties of physicians to patients".[32]

Statement of Marbella

editThe Statement of Marbella was adopted by the 44th World Medical Assembly in Marbella, Spain, in 1992. It provides that "physician-assisted suicide, like voluntary euthanasia, is unethical and must be condemned by the medical profession."[33]

American Medical Association Code of Ethics

editAs of 2022, the American Medical Association (AMA) opposed medical aid in dying. In response to the ongoing debate about medical aid in dying, the AMA has issued guidance for both those who support and oppose physician-assisted suicide. The AMA Code of Ethics Opinion 5.7 reads that "Physician-assisted suicide is fundamentally incompatible with the physician's role as healer" and that it would be "difficult or impossible to control, and would pose serious societal risks" but does not explicitly prohibit the practice. In the AMA Code of Ethics Opinion 1.1.7, which the AMA states "articulates the thoughtful moral basis for those who support assisted suicide", it is written that outside of specific situations in which physicians have clear obligations, such as emergency care or respect for civil rights, "physicians may be able to act (or refrain from acting) in accordance with the dictates of their conscience without violating their professional obligations."[34]

Religious stances

editReligious stances in favor

editUnitarian Universalism

editAccording to a 1988 General Resolution, "Unitarian Universalists advocate the right to self-determination in dying, and the release from civil or criminal penalties of those who, under proper safeguards, act to honor the right of terminally ill patients to select the time of their own deaths".[35]

Religious stances in opposition

editCatholicism

editThe Catholic Church acknowledges the fact that moral decisions regarding a person's life must be made according to one's own conscience and faith.[36] Catholic tradition has said that one's concern for the suffering of another is not a sufficient reason to decide whether it is appropriate to act upon voluntary euthanasia. According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, "God is the creator and author of all life." In this belief system God created human life, therefore God is the judge of when to end life.[36] From the Catholic Church's perspective, deliberately ending one's life or the life of another is morally wrong and defies the Catholic doctrine. Furthermore, ending one's life deprives that person and his or her loved ones of the time left in life and causes grief and sorrow for those left behind.[37]

Pope Francis[38] is the current dominant figure of the Catholic Church. He affirms that death is a glorious event and should not be decided for by anyone other than God. Pope Francis insinuates that defending life means defending its sacredness.[39] The Catholic Church teaches its followers that the act of euthanasia is unacceptable because it is perceived as a sin, as it goes against one of the Ten Commandments. As implied by the fifth commandment, "Thou shalt not kill (You shall not kill)," the act of assisted suicide contradicts the dignity of human life as well as the respect one has for God.[40][37] Additionally, the Catholic Church recommends that terminally ill patients should receive palliative care, which deals with physical pain while treating psychological and spiritual suffering as well, instead of physician-assisted suicide.[41]

Judaism

editWhile preservation of life is one of the greatest values in Judaism, there are instances of suicide and assisted suicide appearing in the Bible and Rabbinic literature.[42] The medieval authorities debate the legitimacy of those measures and in what limited circumstances they might apply. The conclusion of the majority of later rabbinic authorities, and accepted normative practice within Judaism, is that suicide and assisted suicide can not be sanctioned even for a terminal patient in intractable pain.[43]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

editThe Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) is against assisted suicide and euthanasia, and anyone who takes part in either is regarded as having violated the commandments of God.[44] However the church recognizes that when a person is in the final stages of terminal illness there may be difficult decisions to be taken. The church states that "When dying becomes inevitable, death should be looked upon as a blessing and a purposeful part of an eternal existence. Members should not feel obligated to extend mortal life by means that are unreasonable".[45]

Islam

editAccording to a rigid approach, the Muslim doctor should not intervene directly to voluntarily take the life of the patient, not even out of pity (Islamic Code of Medical Ethics, Kuwait 1981); he must see whether the patient is curable or not, not whether he must continue to live. Similarly, he must not administer drugs that accelerate death, even after an explicit request by relatives; acceleration of this kind would correspond to murder. Quran 3.145 states: "Nor can a soul die except by God's leave, the term being fixed as by writing"; Quran 3.156 continues "It is God that gives Life and Death, and God sees well all that ye do", resulting that God has fixed the length of each life, but leaves room for human efforts to save it when some hope exists. The patient's request for his life to be ended has in part been evaluated by juridical doctrine in some aspects. The four "canonical" Sunnite juridical schools (Hanafi te, Malikite, Shafi 'ite and Hanbalite) were not unanimous in their pronouncements. For all, the request or permission to be killed does not make the action, which remains a murder, lawful; however, the disagreement concerns the possibility of applying punishments to those that cause death: the Hanafi tes are in favour; the Hanbalites, the Shafi 'ites and the Malikites are partly in favour and partly contrary to penal sanctions.[46]

In June 1995 the Muslim Medical Doctors Conference in Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur) reasserted that euthanasia (not better defined) goes against the principles of Islam; this is also valid in the military context, prohibiting a seriously wounded soldier from committing suicide or asking other soldiers to kill him out of pity or to avoid falling into enemy hands.[47]

Organisations taking neutral positions

editThere have been calls for organisations representing medical professionals to take a neutral stance on medical aid in dying, rather than a position of opposition. The reasoning is that this supposedly would better reflect the views of medical professionals and that of wider society, and prevent those bodies from exerting undue influence over the debate.[48][49][50]

The UK Royal College of Nursing voted in July 2009 to move to a neutral position on medical aid in dying.[51]

The California Medical Association dropped its long-standing opposition in 2015 during the debate over whether a medical aid in dying bill should be introduced there, prompted in part by cancer sufferer Brittany Maynard.[52] The California End of Life Option Act was signed into law later that year.

In December 2017, the Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS) voted to repeal their opposition to medical aid in dying and adopt a position of neutrality.[53]

In October 2018, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) voted to adopt a position of neutrality from one of opposition. This is contrary to the position taken by the American Medical Association (AMA), which opposes it.[54]

In January 2019 the British Royal College of Physicians announced it would adopt a position of neutrality until two-thirds of its members think it should either support or oppose the legalization of medical aid in dying.[55]

In September 2021, the largest doctors union in the United Kingdom, the British Medical Association, adopted a neutral stance towards a change in the law on assisted dying, replacing their position of opposition which had been in place since 2006.[56]

Attitudes of healthcare professionals

editIn many medical aid in dying programs, physicians play a significant role, usually expressed as "gatekeeper", often putting them at the forefront of the issue. Decades of opinion research show that physicians in the US and several European countries are less supportive of the legalization of medical aid in dying than the general public.[57] In the US, although "about two-thirds of the American public since the 1970s" have supported legalization, surveys of physicians "rarely show as much as half supporting a move".[57] However, physician and other healthcare professional opinions vary widely on the issue of physician-assisted suicide, as shown in the following tables.

| Study | Population | Willing to Assist | Not Willing to Assist | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Medical Association, 2011[58] | Canadian Medical Association (n=2,125) | 16% | 44% | ||

| Cohen, 1994 (NEJM)[59] | Washington state doctors (n=938) | 40% | 49% | ||

| Lee, 1996 (NEJM)[60] | Oregon state doctors (n=2,761) | 46% | 31% | ||

| Study | Population | In favor of legalization | Not in favor of legalization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medscape Ethics Report, 2014[61] | U.S.-based doctors | 54% | 31% | ||

| Seale, 2009[57] | United Kingdom doctors (n=3,733) | 35% | 62.2% | ||

| Cohen, 1994 (NEJM)[59] | Washington state doctors (n=938) | 53% | 39% | ||

A 2019 survey of US physicians found that 60% of physicians answered 'yes' to the question "Should PAS be legalized in your state?" The survey discovered that physicians are concerned about a possible "slippery slope". 30% agreed that "PAS/AID would lead to the legalization of euthanasia" and 46% agreed that "Health insurance companies would cover PAS/AID over more expensive, possibly life-saving treatments, like chemotherapy".[62] The survey also found that physicians generally misunderstand why patients seek PAS. 49% of physicians agreed that "Most patients who seek PAS/AID do so because of physical pain", whereas studies in Oregon found that "the three most frequently mentioned end-of-life concerns were loss of autonomy (89.5%), decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable (89.5%), and loss of dignity (65.4%)."[63] In addition, the survey found uncertainty about the adequacy of safeguards. While 59% agreed that "Current PAS laws provide adequate safeguards", there was greater concern with respect to specific safeguards. 60% disagreed that "Physicians who are not psychiatrists are sufficiently trained to screen for depression in patients who are seeking PAS" and 60% disagreed that "Most physicians can predict with certainty whether a patient seeking PAS/AID has 6 months or less to live".[62] The concern about adequate safeguards is even greater among Oregon emergency physicians, among whom one study found that “Only 37% indicated that the Oregon initiative has enough safeguards to protect vulnerable persons."[23]

Attitudes toward medical aid in dying vary by health profession as well; an extensive survey of 3,733 medical physicians was sponsored by the National Council for Palliative Care, Age Concern, Help the Hospices, Macmillan Cancer Support, the Motor Neurone Disease Association, the MS Society and Sue Ryder Care showed that opposition to voluntary euthanasia and PAS was highest among Palliative Care and Care of the Elderly specialists, with more than 90% of palliative care specialists against a change in the law.[57]

A 1997 study by Glasgow University's Institute of Law & Ethics in Medicine found pharmacists (72%) and anaesthetists (56%) to be generally in favor of legalizing PAS. Pharmacists were twice as likely as medical GPs to endorse the view that "if a patient has decided to end their own life then doctors should be allowed in law to assist".[64] A report published in January 2017 by NPR suggests that the thoroughness of protections that allow physicians to refrain from participating in the municipalities that legalized assisted suicide within the United States presently creates a lack of access by those who would otherwise be eligible for the practice.[65]

A poll in the United Kingdom showed that 54% of General Practitioners are either supportive or neutral towards the introduction of assisted dying laws.[66] A similar poll on Doctors.net.uk published in the BMJ said that 55% of doctors would support it.[67] In contrast the BMA, which represents doctors in the UK, opposes it.[68]

An anonymous, confidential postal survey of all General Practitioners in Northern Ireland, conducted in the year 2000, found that over 70% of responding GPs were opposed to physician-assisted suicide and voluntary active euthanasia.[69]

Public opinion on medical aid in dying

editU.S. polls

editPolls conducted by Gallup dating back to 1947 posit the question, "When a person has a disease that cannot be cured, do you think doctors should be allowed to end the patient's life by some painless means if the patient and his family request it?" show support for the practice increasing from 37% in 1947 to a plateau of approximately 75% lasting from approximately 1990 to 2005. When the polling question was modified as such so the question posits "severe pain" as opposed to an incurable disease, "legalization" as opposed to generally allowing doctors, and "patient suicide" rather than physician-administered voluntary euthanasia, public support was substantially lower, by approximately 10% to 15%.[21]

A poll conducted by National Journal and Regence Foundation found that both Oregonians and Washingtonians were more familiar with the terminology "end-of-life care" than the rest of the country and residents of both states are slightly more aware of the terms palliative and hospice care.[70]

A survey from the Journal of Palliative Medicine found that family caregivers of patients who chose assisted death were more likely to find positive meaning in caring for a patient and were more prepared for accepting a patient's death than the family caregivers of patients who did not request assisted death.[71]

Legality by country and region

editMedical aid in dying is legal in some countries, under certain circumstances, including Austria,[72][73] Belgium,[74] Canada,[75] Luxembourg,[76] the Netherlands,[77] New Zealand,[78] Portugal,[79][note 1] Spain,[81] Switzerland,[82] parts of the United States (California,[83] Colorado,[84] Hawaii,[85] Maine,[86] Montana,[note 2][87] New Jersey,[88] New Mexico,[89] Oregon,[90] Vermont,[91] Washington[92] and Washington DC[93]) and Australia (New South Wales,[94] Queensland,[95] South Australia,[96] Tasmania,[97] Victoria[98] and Western Australia[99]). The Constitutional Courts of Colombia,[100][101][102] Germany[103] and Italy[104] legalized assisted suicide, but their governments have not legislated or regulated the practice yet.

Australia

editLaws regarding assisted suicide in Australia are a matter for state and territory governments. Physician assisted suicide is currently legal in all Australian states: New South Wales,[94] Victoria,[105] South Australia, Western Australia,[106] Tasmania[107] and Queensland.[108] It remains illegal in all Australian territories, however the Australian Capital Territory plans to legalise this by 2024,[109] and the Northern Territory is holding an investigation due to report in 2024.[110]

Under Victorian law, patients can ask medical practitioners about assisted suicide, and doctors, including conscientious objectors, should refer to appropriately trained colleagues who do not conscientiously object.[111] Health practitioners are restricted from initiating conversation or suggesting VAD to a patient unprompted.

Physician assisted suicide was legal in the Northern Territory for a short time under the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995, until this law was overturned by the Federal Parliament which also removed the ability for territories to pass legislation relating to assisted dying, however this prohibition was repealed in December 2022 with the passing of Restoring Territory Rights Act 2022. The highly controversial 'Euthanasia Machine', the first invented voluntary assisted dying machine of its kind, created by Philip Nitschke, utilised during this period is presently held at London's Science Museum.[112]

Austria

editIn December 2020, the Austrian Constitutional Court ruled that the prohibition of assisted suicide was unconstitutional.[113] In December 2021, the Austrian Parliament legalized assisted suicide for those who are terminally ill or have a permanent, debilitating condition.[114][115]

Belgium

editThe Euthanasia Act legalized voluntary euthanasia in Belgium in 2002,[116][117] but it did not cover physician-assisted suicide.[118]

Canada

editIn Canada, physician-assisted suicide was first legalized in the province of Quebec on 5 June 2014.[119] It was declared nationally legal by the Supreme Court of Canada on 6 February 2015, in Carter v. Canada (Attorney General).[120]

National legislation formalizing physician-assisted suicide passed in mid-June 2016, for patients facing an estimated death within six months.[121] Eligibility criteria have been progressively expanded over time. As of March 2021, individuals no longer need to be terminally ill in order to qualify for assisted suicide.[122] Legislation allowing for assisted suicide for mental illness was expected to come into force on 17 March 2023, but has since been postponed until 2027.[123]

Between 10 December 2015 and 30 June 2017, 2,149 medically assisted deaths were documented in Canada. Research published by Health Canada illustrates physician preference for physician-administered voluntary euthanasia, citing concerns about effective administration and prevention of the potential complications of self-administration by patients.[124]

China

editIn China, assisted suicide is illegal under Articles 232 and 233 of the Criminal Law of the People's Republic of China.[125] In China, suicide or neglect is considered homicide and can be punished by three to seven years in prison.[126] In May 2011, Zhong Yichun, a farmer, was sentenced to two years imprisonment by the People's Court of Longnan County, in China's Jiangxi Province for assisting Zeng Qianxiang to die by suicide. Zeng had a mental illness and repeatedly asked Zhong to help him die by suicide. In October 2010, Zeng took excessive sleeping pills and lay in a cave. As planned, Zhong called him 15 minutes later to confirm that he was dead and buried him. However, according to the autopsy report, the cause of death was from suffocation, not an overdose. Zhong was convicted of criminal negligence. In August 2011, Zhong appealed the court sentence, but it was rejected.[126]

In 1992, a physician was accused of murdering a patient with advanced cancer by lethal injection. He was eventually acquitted.[126]

Colombia

editIn May 1997 the Colombian Constitutional Court allowed for the voluntary euthanasia of sick patients who requested to end their lives, by passing Article 326 of the 1980 Penal Code.[127] This ruling owes its success to the efforts of a group that strongly opposed voluntary euthanasia. When one of its members brought a lawsuit to the Colombian Supreme Court against it, the court issued a 6 to 3 decision that "spelled out the rights of a terminally ill person to engage in voluntary euthanasia".[128]

Denmark

editAssisted suicide is illegal in Denmark. Passive euthanasia, or the refusal to accept treatment, is not illegal. A survey from 2014 found that 71% of Denmark's population was in favor of legalizing voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide.[129]

France

editAssisted suicide is not legal in France. The controversy over legalising voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide is not as big as in the United States because of the country's "well developed hospice care programme".[130] However, in 2000 the controversy over the topic was ignited with Vincent Humbert. After a car crash that left him "unable to 'walk, see, speak, smell or taste'", he used the movement of his right thumb to write a book, I Ask the Right to Die (Je vous demande le droit de mourir), in which he voiced his desire to "die legally".[130] After his appeal was denied, his mother assisted in killing him by injecting him with an overdose of barbiturates that put him into a coma, killing him two days later. Though his mother was arrested for aiding in her son's death and later acquitted, the case did jump-start new legislation which states that when medicine serves "no other purpose than the artificial support of life" it can be "suspended or not undertaken".[131]

Germany

editKilling somebody in accordance with their demands is always illegal under the German criminal code (Paragraph 216, "Killing at the request of the victim").[132]

That said, assisting suicide is now generally legal as the Federal Constitutional Court has ruled in 2020 that it is generally protected under the Basic Law. This milestone decision overturned a ban on the commercialization of assisted suicide and set out an entirely new course for countries or jurisdictions contemplating such a provision.[113] Since suicide itself is legal, assistance or encouragement is not punishable by the usual legal mechanisms dealing with complicity and incitement (German criminal law follows the idea of "accessories of complicity" which states that "the motives of a person who incites another person to commit suicide, or who assists in its commission, are irrelevant").[133] Whereas the traditional approach for establishing an assisted dying service has always been based on identifying criteria for who was eligible for it predicated on a view regarding a person's acceptable quality of life (e.g. condition of health or illness), the ruling by the German court stated that government in pluralist societies can not do so as it would violate one's autonomy, the principle of person-state separation. That suggests an alternative model for an assisted dying regime similar to that in Switzerland where no government legislated regime was created but where the provision has existed for decades.[134]

Travel to Switzerland

editBetween 1998 and 2018 around 1250 German citizens (almost three times the number of any other nationality) travelled to Dignitas in Zurich, Switzerland, for an assisted suicide, where this has been legal since 1998.[135][unreliable source?][136] Switzerland is one of the few countries that permit assisted suicide for non-resident foreigners.[137]

Physician-assisted suicide

editPhysician-assisted suicide was formally legalised on 26 February 2020 when Germany's top court removed the prohibition of "professionally assisted suicide".[138]

Iceland

editAssisted suicide is illegal.[139]

Ireland

editAssisted suicide is illegal. "Both euthanasia and assisted suicide are illegal under Irish law. Depending on the circumstances, euthanasia is regarded as either manslaughter or murder and is punishable by up to life imprisonment."[140]

Italy

editOn 25 September 2019, the Italian Constitutional Court ruling 242/2019 declared that article 580 of the criminal code was unconstitutional; the decriminalisation of assisted suicide in the case of those who aid people who suffer from an irreversible pathology to die, effectively legalised assisted suicide.[141] The Italian Parliament has not yet passed a law regulating assisted suicide. On 16 June 2022, the first assisted suicide was performed.[142][143]

Jersey

editOn 25 November 2021, the States Assembly voted to legalise assisted dying and a law legalising it will be drafted in due course.[144] The Channel Island is the first country in the British Islands to approve the measure.[145] The proposition, which was lodged by the Council of Ministers, proposes that a legal assisted dying service should be set up for residents over the age of 18 with a terminal illness or other incurable suffering. The service will be voluntary and methods are either physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia.[146]

This follows a campaign and overwhelming public support. Paul Gazzard and his late husband Alain du Chemin were key actors in the campaign in favour of legalising assisted dying. A citizen's jury was established, which recommended that assisted dying be legalised in the island.[145]

Luxembourg

editAfter again failing to get royal assent for legalizing voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, in December 2008 Luxembourg's parliament amended the country's constitution to take this power away from the monarch, the Grand Duke of Luxembourg.[147] Voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide were legalized in the country in April 2009.[148]

Netherlands

editThe Netherlands was the first country in the world to formally legalise voluntary euthanasia.[149] Physician-assisted suicide is legal under the same conditions as voluntary euthanasia. Physician-assisted suicide became allowed under the Act of 2001 which states the specific procedures and requirements needed in order to provide such assistance. Assisted suicide in the Netherlands follows a medical model which means that only doctors of patients who are suffering "unbearably without hope"[150] are allowed to grant a request for an assisted suicide. The Netherlands allows people over the age of 12 to pursue an assisted suicide when deemed necessary.

New Zealand

editAssisted suicide was decriminalised after a binding referendum in 2020 on New Zealand's End of Life Choice Act 2019. The legislation provided for a year-long delay before it took effect on 6 November 2021.[151] Under Section 179 of the Crimes Act 1961, it is illegal to 'aid and abet suicide' and this will remain the case outside the framework established under the End of Life Choice Act.

Norway

editAssisted suicide is illegal in Norway. It is considered murder and is punishable by up to 21 years imprisonment.

Portugal

editThe Law n.º 22/2023, of 22 May,[152] legalized physician-assisted death, which can be done by physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia. Physician-assisted death can only be permitted to adults, by their own decision, who are experiencing suffering of great intensity and who have a permanent injury of extreme severity or a serious and incurable disease.

The law is not yet in force, because the government has to regulate it first. It states in Article 31 that the regulation must be approved within 90 days of the publishing of the law, which would have been 23 August 2023. However, the regulation has not yet been approved by the government. According to Article 34, the law will only enter into force 30 days after the regulation is published. On 24 November 2023, the Ministry of Health said the regulation of the law would be the responsibility of the new government elected in the 10 March 2024 elections.[80]

South Africa

editSouth Africa is struggling with the debate over legalizing voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Owing to the underdeveloped health care system that pervades the majority of the country, Willem Landman, "a member of the South African Law Commission, at a symposium on euthanasia at the World Congress of Family Doctors" stated that many South African doctors would be willing to perform acts of voluntary euthanasia when it became legalized in the country.[153] He feels that because of the lack of doctors in the country, "[legalizing] euthanasia in South Africa would be premature and difficult to put into practice ...".[153]

On 30 April 2015, the High Court in Pretoria granted Advocate Robin Stransham-Ford an order that would allow a doctor to assist him in taking his own life without the threat of prosecution. On 6 December 2016, the Supreme Court of Appeal overturned the High Court ruling.[154]

Switzerland

editThough it is illegal to assist a patient in dying in some circumstances, there are others where there is no offence committed.[155] The relevant provision of the Swiss Criminal Code[156] refers to "a person who, for selfish reasons, incites someone to commit suicide or who assists that person in doing so will, if the suicide was carried out or attempted, be sentenced to a term of imprisonment (Zuchthaus) of up to 5 years or a term of imprisonment (Gefängnis)."

A person brought to court on a charge could presumably avoid conviction by proving that they were "motivated by the good intentions of bringing about a requested death for the purposes of relieving "suffering" rather than for "selfish" reasons.[157] In order to avoid conviction, the person has to prove that the deceased knew what he or she was doing, had the capacity to make the decision, and had made an "earnest" request, meaning they asked for death several times. The person helping also has to avoid actually doing the act that leads to death, lest they be convicted under Article 114: Killing on request (Tötung auf Verlangen) – A person who, for decent reasons, especially compassion, kills a person on the basis of his or her serious and insistent request, will be sentenced to a term of imprisonment (Gefängnis). For instance, it should be the suicide subject who actually presses the syringe or takes the pill, after the helper had prepared the setup.[158] This way the country can criminalise certain controversial acts, which many of its people would oppose, while legalising a narrow range of assistive acts for some of those seeking help to end their lives.

Switzerland is the only country in the world which permits assisted suicide for non-resident foreigners,[159][137] causing what some critics have described as suicide tourism. Between 1998 and 2018 around 1250 German citizens (almost three times the number of any other nationality) travelled to Dignitas in Zurich, Switzerland, for an assisted suicide. During the same period over 400 British citizens also opted to end their life at the same clinic.[135][136]

In May 2011, Zurich held a referendum that asked voters whether (i) assisted suicide should be prohibited outright; and (ii) whether Dignitas and other assisted suicide providers should not admit overseas users. Zurich voters heavily rejected both bans, despite anti-euthanasia lobbying from two Swiss social conservative political parties, the Evangelical People's Party of Switzerland and Federal Democratic Union. The outright ban proposal was rejected by 84% of voters, while 78% voted to keep services open should overseas users require them.[160]

In Switzerland non-physician-assisted suicide is legal, the assistance mostly being provided by volunteers, whereas in Belgium and the Netherlands, a physician must be present. In Switzerland, the doctors are primarily there to assess the patient's decision capacity and prescribe the lethal drugs. Additionally, unlike cases in the United States, a person is not required to have a terminal illness but only the capacity to make decisions. About 25% of people in Switzerland who take advantage of assisted suicide do not have a terminal illness but are simply old or "tired of life".[161]

United Kingdom

editEngland and Wales

editDeliberately assisting a suicide is illegal.[162] Between 2003 and 2006, Lord Joffe made four attempts to introduce bills that would have legalised physician-assisted suicide in England and Wales. All were rejected by the UK Parliament.[163] In the meantime, the Director of Public Prosecutions has clarified the criteria under which an individual will be prosecuted in England and Wales for assisting in another person's suicide.[164] These have not been tested by an appellate court as yet.[165] In 2014, Lord Falconer of Thoroton tabled an Assisted Dying Bill in the House of Lords which passed its Second Reading but ran out of time before the general election. During its passage peers voted down two amendments which were proposed by opponents of the Bill. In 2015, Labour MP Rob Marris introduced another Bill, based on the Falconer proposals, in the House of Commons. The Second Reading was the first time the House was able to vote on the issue since 1997. A Populus poll had found that 82% of the British public agreed with the proposals of Lord Falconer's Assisted Dying Bill.[166] However, in a free vote on 11 September 2015, only 118 MPs were in favour and 330 against, thus defeating the bill.[167]

Scotland

editUnlike the other jurisdictions in the United Kingdom, suicide was not illegal in Scotland before 1961 (and still is not) thus no associated offences were created in imitation. Depending on the actual nature of any assistance given to a suicide, the offences of murder or culpable homicide might be committed or there might be no offence at all; the nearest modern prosecutions bearing comparison might be those where a culpable homicide conviction has been obtained when drug addicts have died unintentionally after being given "hands on" non-medical assistance with an injection. Modern law regarding the assistance of someone who intends to die has a lack of certainty as well as a lack of relevant case law; this has led to attempts to introduce statutes providing more certainty.

Independent MSP Margo MacDonald's "End of Life Assistance Bill" was brought before the Scottish Parliament to permit physician-assisted suicide in January 2010. The Catholic Church and the Church of Scotland, the largest denomination in Scotland, opposed the bill. The bill was rejected by a vote of 85–16 (with 2 abstentions) in December 2010.[168][169]

The Assisted Suicide (Scotland) Bill was introduced on 13 November 2013 by the late Margo MacDonald MSP and was taken up by Patrick Harvie MSP on Ms MacDonald's death. The Bill entered the main committee scrutiny stage in January 2015 and reached a vote in Parliament several months later; however the bill was again rejected.

Northern Ireland

editHealth is a devolved matter in the United Kingdom and as such it would be for the Northern Ireland Assembly to legislate for assisted dying as it sees fit. As of 2018, there has been no such bill tabled in the Assembly.

United States

edit1 In its 2009 decision Baxter v. Montana, the Montana Supreme Court ruled that assisted suicide did not violate Montana legal precedent or state statutes, even though no Montana laws specifically allowed it.

Physician-assisted dying was first legalized by the 1994 Oregon Death with Dignity Act, with effect delayed by lawsuits until 1997.[170] The Montana Supreme Court ruled in Baxter v. Montana (2009) that it found no state law or public policy reason that would prohibit physician-assisted dying.[87]

It was legalized by Washington (state) in 2008,[171] Vermont in 2013,[172] California[173][174] and Washington, D.C.,[175] and Colorado[176] in 2016, Hawaii in 2018,[177] New Jersey in 2019,[178] Maine in 2020,[179][180] and New Mexico in 2021[181] It had also been briefly legal in New Mexico in 2014 and 2015 due to a court decision that was overturned.

Access to the procedure is generally restricted to people with a terminal illness and less than six months to live. Patients are generally required to be mentally healthy, to get approval from multiple doctors, and to affirm the request multiple times.

The punishment for participating in physician-assisted death varies throughout the other states. The state of Wyoming does not "recognize common law crimes and does not have a statute specifically prohibiting physician-assisted suicide". In Florida, "every person deliberately assisting another in the commission of self-murder shall be guilty of manslaughter, a felony of the second degree".[182]

Uruguay

editAssisted suicide, while criminal, does not appear to have caused any convictions, as article 37 of the Penal Code (effective 1934) states: "The judges are authorized to forego punishment of a person whose previous life has been honorable where he commits a homicide motivated by compassion, induced by repeated requests of the victim."[183]

Safeguards

editMany current assisted death laws contain provisions that are intended to provide oversight and investigative processes to prevent abuse. This includes eligibility and qualification processes, mandatory state reporting by the medical team, and medical board oversight. In Oregon and other states, two doctors and two witnesses must assert that a person's request for a lethal prescription was not coerced or under undue influence.

These safeguards include proving one's residency and eligibility. The patient must meet with two physicians and they must confirm the diagnoses before one can continue the procedure; in some cases, they do include a psychiatric evaluation as well to determine whether or not the patient is making this decision on their own. The next steps are two oral requests, a waiting period of a minimum of 15 days before making the next request. A written request which must be witnessed by two different people, one of which cannot be a family member, and then another waiting period by the patient's doctor in which they say whether they are eligible for the drugs or not ("Death with Dignity").

The debate about whether these safeguards work is debated between opponents and proponents.

A 1996 survey of Oregon emergency physicians found that "Only 37% indicated that the Oregon initiative has enough safeguards to protect vulnerable persons."[23]

Criteria

editIn some programs, when death is imminent (half a year or less) patients can choose to have assisted death as a medical option to shorten what the person perceives to be an unbearable dying process.

In Canada and some European countries eligibility also includes ‘unbearable suffering’, i.e. the person does not need to be terminally ill.[25]

In the Dignitas program, criteria include that the person;

- have a disease which will lead to death (terminal illness), and/or an unendurable incapacitating disability, and/or unbearable and uncontrollable pain.

- be of sound judgement

- be able themselves to action the last stage – to swallow, administer the gastric tube or open the valve of the intravenous access tube.[184][185]

Methods

editMedications

editAssisted suicide is typically undertaken using medications.[186][187]

In Canada a sequence of midazolam, propofol and rocuronium is used.[188]

In the Netherlands very high-dose barbiturates were recommended by the Netherland's Guidelines for the Practice of Euthanasia.[189][190]

In Oregon, in 2022, more than 70% of ingestions used the drug combination DDMAPh (diazepam, digoxin, morphine sulfate, amitriptyline, phenobarbital),[191][192] and 28% used the drug combination DDMA (diazepam, digoxin, morphine sulfate, amitriptyline). These medication combinations have largely replaced the use of individual medications in previous years. Over 2001–22, the median time to death for DDMAPh was 42 minutes and for DDMA 49 minutes. [193]

Other US states also use drug combinations in assisted suicide programs.[189]

In the Dignitas program in Switzerland, after taking an anti-emetic, the person ingests sodium pentobarbital (NaP), usually 15 grams. This is normally drunk in water, but may be ingested by gastric tube or intravenously.[184] In the Swiss Pegasos program, sodium pentobarbital is taken intravenously.[194]

Medications that have been used in assisted suicide include

- Barbiturates, particularly secobarbital (brand name Seconal)[196][197] and pentobarbital[198][199]

- propofol[200]

- midazolam[200]

- rocuronium[200]

- Combinations of medications are sometimes used.[196]

Other medications and medication combinations have been considered.[201][202]

Gases

editInert gas asphyxiation by nitrogen has been used in assisted suicide[203] (and also in legal execution[204]).

Medical staff, provider or other person may be present

editMedical staff may be involved as 'gatekeepers'. Volunteers may be present. However, in the Oregon programme in 2022, no provider or volunteer was present in 28% of cases when meds were ingested, and in 55% of cases at time of death.[205]

Duo-euthanasia

editIn duo-euthanasia partners die together. In the Netherlands 66 people (33 couples) died by duo-euthanasia in 2023. [206][207][208]

Organ donation

editIn the Netherlands assisted dying followed by organ donation is legal.[187]

Statistics on medical aid in dying programs

editStatistics by leading countries

editCountries with the highest levels of assisted dying, as of 2021 data, are

- Canada 10,064

- Netherlands 7,666

- Belgium 2,699

- USA 1,300+[209]

In Canada assisted deaths of 13,241 in 2022 made up more than 4% of all deaths.[209]

In the Netherlands deaths by euthanasia in 2023 were 9,068, an increase of 4% on 2022. These deaths were 5% of all deaths.[210]

In California 853 assisted deaths were recorded in 2022.[209]

Oregon

editIn the Oregon program 2454 deaths had occurred from 2001 to 2022.

During 2022, 431 people (384 in 2021) received prescriptions for lethal doses of medications under the provisions of the Oregon DWDA, and at January 20, 2023, OHA had received reports of 278 of these people (255 in 2021) dying through ingesting those medications. 85% were aged 65 years or older, and 96% were white. The most common underlying illnesses were cancer (64%), heart disease (12%) and neurological disease (10%). 92% died at home. (See the arguments section above for reasons for using the program, and the methods section above for further information.)[19]

In February 2016, Oregon released a report on its 2015 numbers. In 2015, there were 218 people in the state who were approved and received the lethal drugs to end their own life. Of that 218, 125 have been confirmed to have ultimately decided to ingest drugs, resulting in their death. 50 did not ingest medication and died from other means, while the ingestion status of the remaining 43 is unknown. According to the state of Oregon Public Health Division's survey, the majority of the participants, 78%, were 65 years of age or older and predominantly white, 93.1%. 72% of the terminally ill patients who opted for ending their own lives had been diagnosed with some form of cancer. In the state of Oregon's 2015 survey, they asked the terminally ill who were participating in medical aid in dying, what their biggest end-of-life concerns were: 96.2% of those people mentioned the loss of the ability to participate in activities that once made them enjoy life, 92.4% mentioned the loss of autonomy, or the independence of their own thoughts or actions, and 75.4% stated loss of their dignity.[211]

A 2015 Journal of Palliative Medicine report on patterns of hospice use noted that Oregon was in both the highest quartile of hospice use and the lowest quartile of potentially concerning patterns of hospice use. A similar trend was found in Vermont, where aid-in-dying (AiD) was authorized in 2013.[212]

A 2002 study of hospice nurses and social workers in Oregon reported that symptoms of pain, depression, anxiety, extreme air hunger and fear of the process of dying were more pronounced among hospice patients who did not request a lethal prescription for barbiturates, the drug used for physician-assisted death.[213]

Washington State

editAn increasing trend in deaths caused by ingesting lethal doses of medications prescribed by physicians was also noted in Washington: from 64 deaths in 2009 to 202 deaths in 2015.[214] Among the deceased, 72% had terminal cancer and 8% had neurodegenerative diseases (including ALS).[214]

Dignitas

edit250 accompanied suicides took place under the Dignitas program in Switzerland in 2023.[215]

Publicized cases

editIn January 2006, British doctor Anne Turner took her own life in a Zurich clinic having developed an incurable degenerative disease. Her story was reported by the BBC and later, in 2009, made into a TV film A Short Stay in Switzerland starring Julie Walters.

In July 2009, British conductor Sir Edward Downes and his wife Joan died together at a suicide clinic outside Zürich "under circumstances of their own choosing". Sir Edward was not terminally ill, but his wife was diagnosed with rapidly developing cancer.[216]

In March 2010, the American PBS TV program Frontline showed a documentary called The Suicide Tourist which told the story of Professor Craig Ewert, his family, and Dignitas, and his decision to die by assisted suicide using sodium pentobarbital in Switzerland after he was diagnosed and suffering with ALS (Lou Gehrig's disease).[217]

In June 2011, the BBC televised the assisted suicide of Peter Smedley, a canning factory owner, who was suffering from motor neurone disease. The programme – Terry Pratchett: Choosing to Die – told the story of Smedley's journey to the end where he used The Dignitas Clinic, a voluntary euthanasia clinic in Switzerland, to assist him in carrying out his suicide. The programme shows Smedley eating chocolates to counter the unpalatable taste of the liquid he drinks to end his life. Moments after drinking the liquid, Smedley begged for water, gasped for breath and became red, he then fell into a deep sleep where he snored heavily while holding his wife's hand. Minutes later, Smedley stopped breathing and his heart stopped beating.

In Colombia in January 2022 Victor Escobar became the first person with a non-terminal illness to die by legally regulated euthanasia. The 60-year-old Escobar had end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[218]

Organisations active in assisted suicide

editDeath with Dignity National Center is coined as the United States national leader in end of life advocacy and policy reform. The organization has been advocating for physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia since 1994.[219]

Care Not Killing is a UK organisation opposed to euthanasia.[220]

See also

edit- Bioethics

- Betty and George Coumbias

- Consensual homicide

- Euthanasia device

- Jack Kevorkian

- Legality of euthanasia

- List of deaths from legal euthanasia and assisted suicide

- Brittany Maynard

- Philip Nitschke

- Right to Die? (2008 film)

- Senicide

- A Short Stay in Switzerland (2009 film)

- Suicide by cop

- Suicide legislation

- You Don't Know Jack (2010 film)

- The Chalice of Courage (1915 film)

Explanatory notes

edit- ^ a b c Portugal: Law not yet in force, awaits regulation to be implemented. The law legalizing physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia, Law n.º 22/2023, of 22 May,[79] states in Article 31 that the regulation must be approved within 90 days of the publishing of the law, which would have been 23 August 2023. However, the regulation has not yet been approved by the government. On 24 November 2023, the Ministry of Health stated that the regulation of the law would be the responsibility of the new government elected in the 10 March 2024 elections.[80] The law, according to its Article 34, will only enter into force 30 days after the regulation is published.

- ^ See Baxter v. Montana.

References

edit- ^ "assisted suicide". Encyclopaedia Brittanica. 30 October 2023. Archived from the original on 9 November 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "Medical Aid In Dying Is Not Assisted Suicide, Suicide or Euthanasia - Compassion & Choices". compassionandchoices.org/. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ "physician-assisted suicide". July 2020. Archived from the original on 9 November 2023.

- ^ "Spain passes law allowing euthanasia". BBC News. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "EUTHANASIA AND ASSISTED SUICIDE (UPDATE 2007)" (PDF). Canadian Medical Association. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2011.

- ^ "Assisted dying/assisted suicide - Committees - UK Parliament".

- ^ "What do assisted dying, assisted suicide and euthanasia mean and what is the law?". BBC News. 8 February 2019.

- ^ "What are euthanasia and assisted suicide?". Medical News Today. 17 December 2018. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "Suicidism". Webster's 1913 Dictionary. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "A Q&A with Alexandre Baril". 31 May 2023.

- ^ "Don't Say It's Selfish: Suicide Is Not a Choice". www.nationwidechildrens.org.

- ^ Suicidism has been described as "an oppressive system (stemming from non-suicidal perspectives) functioning at the normative, discursive, medical, legal, social, political, economic, and epistemic levels in which suicidal people experience multiple forms of injustice and violence..."Baril A (2020). "Suicidism: A new theoretical framework to conceptualize suicide from an anti-oppressive perspective". Disability Studies Quarterly. 40 (3): 1–41. doi:10.18061/dsq.v40i3.7053. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ "ASSISTED DYING NOT ASSISTED SUICIDE". Dignity in Dying. 10 April 2013. Archived from the original on 6 April 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ "Why medically assisted dying is not suicide". Dying with Dignity Canada. Archived from the original on 6 April 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ "Assisted dying around the world: a status quaestionis". Annals of Palliative Medicine. 10 (3). March 2021. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ "Las justificaciones de la muerte asistida". Recerca Revista de pensament i anàlisi. 25 (2). 2020.

- ^ Starks H. "Physician Aid-in-Dying". Physician Aid-in-Dying: Ethics in Medicine. University of Washington School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Baril A (2020). "Suicidism: A new theoretical framework to conceptualize suicide from an anti-oppressive perspective". Disability Studies Quarterly. 40 (3): 1–41. doi:10.18061/dsq.v40i3.7053. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ a b Oregon Death with Dignity Act 2022 data summary https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PROVIDERPARTNERRESOURCES/EVALUATIONRESEARCH/DEATHWITHDIGNITYACT/Documents/year25.pdf

- ^ The three most frequently mentioned end-of-life concerns reported by Oregon residents who took advantage of the Death With Dignity Act in 2015 were: decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable (96.2%), loss of autonomy (92.4%), and loss of dignity (75.4%)."OREGON DEATH WITH DIGNITY ACT: 2015 DATA SUMMARY" (PDF). Oregon.gov. Oregon Health Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ a b Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J (July 2016). "Attitudes and Practices of Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe". JAMA. 316 (1): 79–90. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.8499. PMID 27380345.

- ^ a b Mayo DJ, Gunderson M (July 2002). "Vitalism revitalized.... Vulnerable populations, prejudice, and physician-assisted death". The Hastings Center Report. 32 (4): 14–21. doi:10.2307/3528084. JSTOR 3528084. PMID 12362519.

- ^ a b c Schmidt TA, Zechnich AD, Tilden VP, Lee MA, Ganzini L, Nelson HD, Tolle SW (October 1996). "Oregon emergency physicians' experiences with, attitudes toward, and concerns about physician-assisted suicide". Academic Emergency Medicine. 3 (10): 938–945. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03323.x. PMID 8891040.

- ^ Douthat R (6 September 2009). "A More Perfect Death". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ a b "Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill publications - Parliamentary Bills - UK Parliament".

- ^ Kass L (1989). "Neither for love nor money: why doctors must not kill" (PDF). The Public Interest. 94 (94): 25–46. PMID 11651967. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "The Internet Classics Archive – The Oath by Hippocrates". mit.edu. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ "Hippocratic oath". Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 May 2024. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ "Greek Medicine – The Hippocratic Oath". History of Medicine. 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Oxtoby K (14 December 2016). "Is the Hippocratic oath still relevant to practicing doctors today?". BMJ: i6629. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6629.

- ^ "WMA DECLARATION OF GENEVA". www.wma.net. 6 November 2017. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "WMA International Code of Medical Ethics". wma.net. 1 October 2006. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "WMA Statement on Physician-Assisted Suicide". wma.net. 1 May 2005. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "Physician-Assisted Suicide". American Medical Association. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "The Right to Die with Dignity: 1988 General Resolution". Unitarian Universalist Association. 24 August 2011. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ a b Donovan GK (December 1997). "Decisions at the end of life: Catholic tradition". Christian Bioethics. 3 (3): 188–203. doi:10.1093/cb/3.3.188. PMID 11655313.

- ^ a b Harvey K (2016). "Mercy and Physician-Assisted Suicide". Ethics & Medics. 41 (6): 1–2. doi:10.5840/em201641611.

- ^ "Pope Francis Biography". 20 April 2021. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Cherry MJ (6 February 2015). "Pope Francis, Weak Theology, and the Subtle Transformation of Roman Catholic Bioethics". Christian Bioethics. 21 (1): 84–88. doi:10.1093/cb/cbu045.

- ^ "Roman Catholicism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Yao T (2016). "Can We Limit a Right to Physician-Assisted Suicide?". The National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly. 16 (3): 385–392. doi:10.5840/ncbq201616336.

- ^ Samuel 1:31:4–5, Daat Zekeinim Baalei Hatosfot Genesis 9:5.

- ^ Steinberg A (1988). Encyclopedia Hilchatit Refuit. Vol. 1. Jerusalem: Shaarei Zedek Hospital. p. 15.

- ^ "Handbook 2: Administering the Church – 21.3 Medical and Health Policies". Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ "Euthanasia and Prolonging Life". LDS News. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ Nohra F (1 December 2014). "Pouvoir politique, droits fondamentaux et droit à la révolte : la doctrine religieuse face aux processus révolutionnaires dans le monde arabe". Revue des droits de l'homme (6). doi:10.4000/revdh.922. ISSN 2264-119X. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ Gurcum BH, Ozcan N (31 August 2016). "Searching for Form in Textile Art with Traditional Cit Weaving". Idil Journal of Art and Language. 5 (24). doi:10.7816/idil-05-24-10. ISSN 2146-9903.

- ^ Godlee F (8 February 2018). "Assisted dying: it's time to poll UK doctors". BMJ: k593. doi:10.1136/bmj.k593.

- ^ "'Neutrality' on assisted suicide is a step forward". Nursing Times. 31 July 2009. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Gerada C (December 2012). "The case for neutrality on assisted dying – a personal view". The British Journal of General Practice. 62 (605): 650. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X659376. PMC 3505400. PMID 23211247.

- ^ "RCN Position statement on assisted dying" (PDF). Royal College of Nursing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ "California Medical Association drops opposition to doctor-assisted suicide". Reuters. 20 May 2015. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ "Massachusetts Medical Society adopts several organizational policies at Interim Meeting". Massachusetts Medical Society. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "COD Addresses Medical Aid in Dying, Institutional Racism". AAFP. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "Doctors to be asked if they would help terminally ill patients die". Chronicle Live. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ "BMA drops opposition to assisted dying and adopts neutral stance". Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d Seale C (April 2009). "Legalisation of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide: survey of doctors' attitudes". Palliative Medicine. 23 (3): 205–212. doi:10.1177/0269216308102041. PMID 19318460. S2CID 43547476.

- ^ Canadian Medical Association (2011). "Physician view on end-of-life issues vary widely: CMA survey" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ a b Cohen JS, Fihn SD, Boyko EJ, Jonsen AR, Wood RW (July 1994). "Attitudes toward assisted suicide and euthanasia among physicians in Washington State". The New England Journal of Medicine. 331 (2): 89–94. doi:10.1056/NEJM199407143310206. PMID 8208272.

- ^ Lee MA, Nelson HD, Tilden VP, Ganzini L, Schmidt TA, Tolle SW (February 1996). "Legalizing assisted suicide—views of physicians in Oregon". The New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (5): 310–315. doi:10.1056/nejm199602013340507. PMID 8532028.

- ^ Kane L. "Medscape Ethics Report 2014, Part 1: Life, Death, and Pain". Medscape. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ a b Hetzler III PT, Nie J, Zhou A, Dugdale LS (December 2019). "A Report of Physicians' Beliefs about Physician-Assisted Suicide: A National Study". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 92 (4): 575–585. PMC 6913834. PMID 31866773.

- ^ "Oregon Death with Dignity Act Data summary" (PDF). oregon.gov/oha. Oregon Health Authority. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ McLean S (1997). Sometimes a Small Victory. Institute of Law and Ethics in Medicine, University of Glasgow.

- ^ Aleccia J (25 January 2017). "Legalizing Aid in Dying Doesn't Mean Patients Have Access To It". NPR. Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ "Public Opinion – Dignity in Dying". Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ "Assisted dying case 'stronger than ever' with majority of doctors now in support". 7 February 2018. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ "Physician-assisted dying – BMA". Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ McGlade KJ, Slaney L, Bunting BP, Gallagher AG (October 2000). "Voluntary euthanasia in Northern Ireland: general practitioners' beliefs, experiences, and actions". The British Journal of General Practice. 50 (459): 794–797. PMC 1313819. PMID 11127168.

- ^ "Living Well at the End of Life Poll" (PDF). The National Journal. February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ Ganzini L, Goy ER, Dobscha SK, Prigerson H (December 2009). "Mental health outcomes of family members of Oregonians who request physician aid in dying". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 38 (6): 807–815. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.026. PMID 19783401.

- ^ "G 139/2019-71. 11. Dezember 2020" (PDF) (in German). Verfassungsgerichtshof. 11 December 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 December 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ "Sterbeverfügungsgesetz; Suchtmittelgesetz, Strafgesetzbuch, Änderung". parlament.gv.at (in German). Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ "28 MEI 2002. — Wet betreffende de euthanasie / 28 MAI 2002. — Loi relative a' l'euthanasie" (PDF) (in Dutch and French). Belgisch Staatsblad / Moniteur Belge. 22 June 2002. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ "Bill C-14. An Act to amend the Criminal Code and to make related amendments to other Acts (medical assistance in dying". parl.ca. Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ "Legislation reglementant les soins palliatifs ainsi que l'euthanasie et l'assistance au suicide" (PDF) (in French). Journal Officiel du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. 16 March 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ "Wet toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding". overheid.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ "End of Life Choice Act". health.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Law n.º 22/2023, of 22 May, published on the 1st Series of Diário da República, n.º 101, of 25 May 2023, in Portuguese, retrieved 25 May 2023".

- ^ a b Caeiro T (24 November 2023). "Eutanásia não avança para já. Ministério da Saúde deixa regulamentação para o próximo governo" [Euthanasia is not moving forward for now. Ministry of Health leaves regulation to the next government]. Observador (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2 December 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Ley Orgánica 3/2021, de 24 de marzo, de regulación de la eutanasia". boe.es (in Spanish). 25 March 2021. pp. 34037–34049. Archived from the original on 5 July 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ "Swiss Criminal Code". fedlex.admin.ch. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ "End of Life Option Act". Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Colorado End-of-Life Options Act". Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Our Care, Our Choice Act" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Death with Dignity Act". Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b Baxter v. State, [1], 224 P.3d 1211, 354 Mont. 234 (2009).

- ^ "Medical Aid in Dying for the Terminally Ill Act". Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Elizabeth Whitefield End-of-Life Options Act" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Death with Dignity Act". Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Patient Choice and Control at End of Life Act". 23 November 2016. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Death with Dignity Act". Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "District of Columbia Death with Dignity Act of 2016, D.C. Law 21-182". Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2021". Archived from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2021" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2020". 22 November 2021. Archived from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "End Of Life Choices (Voluntary Assisted Dying) Bill 2020 (30 of 2020)". Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2017". Archived from the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Voluntary assisted dying". Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Sentencia C-239/97". Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Sentencia T-970/14". Archived from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Sentencia C-164-2022" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ "Zum Urteil des Zweiten Senats vom 26. Februar 2020". 26 February 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Sentenza n. 242/2019" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Voluntary euthanasia is now legal in Victoria". Archived from the original on 7 July 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Voluntary euthanasia becomes law in WA in emotional scenes at Parliament". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 10 December 2019. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ "Tasmania passes voluntary assisted dying legislation, becoming third state to do so". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 23 March 2021. Archived from the original on 27 March 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ "Queensland MPs vote to legalise voluntary assisted dying". The Guardian. 16 September 2021. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Allen C (20 May 2023). "The ACT's proposed voluntary assisted dying laws have yet to be introduced, but could be the most liberal in the country". ABC News. Archived from the original on 20 August 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ Northern Territory Government (2023). "Project Management Office". Department of Chief Minister and Cabinet. Archived from the original on 20 August 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Health practitioner information on voluntary assisted dying". Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Euthanasia machine, Australia, 1995–1996". Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ a b Brade A, Friedrich R (16 January 2021). "Stirb an einem anderen Tag". Verfassungsblog. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ "Austria's parliament legalizes assisted suicide". DW. 16 December 2021. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "New law allowing assisted suicide takes effect in Austria". BBC News. 1 January 2022. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Moniteur Belge – Belgisch Staatsblad". fgov.be (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 9 October 2006.

- ^ "Moniteur Belge – Belgisch Staatsblad". fgov.be (in French). Archived from the original on 9 October 2006.

- ^ Adams M, Nys H (1 September 2003). "Comparative reflections on the Belgian Euthanasia Act 2002". Medical Law Review. 11 (3): 353–376. doi:10.1093/medlaw/11.3.353. PMID 16733879.

- ^ Hamilton G (10 December 2015). "Is it euthanasia or assisted suicide? Quebec's end-of-life care law explained". National Post. Toronto, Ontario. Archived from the original on 12 June 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Carter v. Canada (Attorney General), 2015 S.C.C. 5, [2015] 1 S.C.R. 331. Archived 18 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bill C-14, An Act to amend the Criminal Code & to make related amendments to other Acts (medical assistance in dying), 1st Sess., 42nd Parl., 2015–2016 (assented to 2016‑06‑17), S.C. 2016, c. 3 Archived 5 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Canada Do (18 March 2021). "New medical assistance in dying legislation becomes law". www.canada.ca. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Canada H (16 June 2016). "Medical assistance in dying". www.canada.ca. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Health Canada (October 2017), Second Interim Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada (PDF), Ottawa: Health Canada, ISBN 978-0-660-20467-3, H14‑230/2‑2017E‑PDF, archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2021, retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Euthanasia & Physician-Assisted Suicide (PAS) around the World - Euthanasia - ProCon.org". euthanasia.procon.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ a b c Zeldin W (17 August 2011). "China: Case of Assisted Suicide Stirs Euthanasia Debate". The Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ McDougall & Gorman 2008

- ^ Whiting R (2002). A Natural Right to Die: Twenty-Three Centuries of Debate. Westport, Connecticut. pp. 41. ISBN 978-0-313-31474-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Nielsen ME, Andersen MM (July 2014). "Bioethics in Denmark. Moving from first- to second-order analysis?" (PDF). Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 23 (3): 326–333. doi:10.1017/S0963180113000935. PMID 24867435. S2CID 6706267. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ a b McDougall & Gorman 2008, p. 84

- ^ McDougall & Gorman 2008, p. 86

- ^ "German Criminal Code". German Federal Ministry of Justice. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Wolfslast G (2008). "Physician-Assisted Suicide and the German Criminal Law". Giving Death a Helping Hand. International Library of Ethics, Law, and the New Medicine. Vol. 38. pp. 87–95. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6496-8_8. ISBN 978-1-4020-6495-1.

- ^ Dankwort, J. 6 April 2023.Overcoming impediments to medically assisted dying: A signal for another approach? Journal of Medical Ethics Forum. Accessed 14 September 2023. https://blogs.bmj.com/medical-ethics/2023/04/06/overcoming-impediments-to-medically-assisted-dying-a-signal-for-another-approach/ Archived 23 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Statistiken". Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2020.