Atlixco (Nahuatl pronunciation: [aːˈt͡ɬiːʃko] ) is a city in the Mexican state of Puebla. It is a regional industrial and commercial center but economically it is much better known for its production of ornamental plants and cut flowers. The city was founded early in the colonial period, originally under the jurisdiction of Huejotzingo, but eventually separated to become an independent municipality. The municipality has a number of notable cultural events, the most important of which is the El Huey Atlixcayotl, a modern adaptation of an old indigenous celebration. This event brings anywhere from 800 to 1,500 participants from all over the state of Puebla to create music, dance, and other cultural and artistic performances. Atlixco joined the UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities in 2018.[1]

Atlixco

Atlixco de las Flores | |

|---|---|

| Heroica Atlixco | |

| |

| Coordinates: 18°54′N 98°27′W / 18.900°N 98.450°W | |

| Country | |

| State | Puebla |

| Founded | 1579 |

| Municipal Status | 1706 |

| Government | |

| • Municipal President | Ariadna Ayala Camarillo (PT) |

| Area | |

• Total | 229.22 km2 (88.50 sq mi) |

| Elevation (of seat) | 1,035 m (3,396 ft) |

| Population (2008) Municipality | |

• Total | 125,000 |

| • Seat density | 1,035/km2 (2,680/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (US Central)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (Central) |

| Postal code (of seat) | 21019 |

| Area code | 33 |

| Demonym | Atlixquense |

| Website | (in Spanish) Municipal Official Site |

History

editThe name "Atlixco" comes from a Nahuatl phrase which can be interpreted as either "water in the valley" or "water on the ground".[2] Its main economic activity has earned the city the suffix of de las flores ("of the flowers").[3] The city of Atlixco received its coat of arms from King Philip II in 1579, which now represents the entire municipality.[2]

Pre-Hispanic period

editIn the pre-Hispanic period, it was part of Cuauhquecollán, today Huaquechula. The first known inhabitants of this area were the Teochichimecas around 1100 CE, before becoming a Xicalanca settlement. This area was eventually conquered by Tenochtitlan. Its location made it a battleground among several indigenous peoples, with the populations of Calpan, Huejotzingo and Cholula claiming possession. After the Conquest it was named Acapetlahuacan (place of reeds) until its current name.[2]

Colonial period

editDuring the colonial period, the area was an important producer of grain, especially wheat, giving rise to the first wheat mill in the state.[3] The city proper was founded in 1579 as Villas de Carrión by Pedro de Castillo, Cristóbal Ruiz de Cabrera and Alonso Díaz de Carrión.[2][4]

Province of Carrión in the Valley of Atlixco

editOriginally it and the surrounding area was under the jurisdiction of Huejotzingo, but in 1632, it became a local independent seat of government.[2] In 1693, Don Diego Fernández de Medrano y Zapata, a native of Sojuela and resident of Logroño, owner of the Divisa Regajal,[5] knight of the Order of Calatrava, became the Governor of the Province of Carrión, valley of Atlixco in Puebla, with his seat in the city of Atlixco.[6][7]

Duchy of Atlixco

editIn 1706 the area became under the direct control of the Spanish Crown, with Philip V granting José Sarmiento Valladares Arines de Romay the royal title of Duke and Lord of Atlixco.[2]

Notable visits

editIn 1840 the Marquesa Calderón de la Barca visited the community and noted that it was filled with beautiful churches, monasteries and other buildings.[3]

City of Atlixco

editThe town was given the official status of city by Nicolás Bravo in 1843. In 1847, the municipal government took over administration of the San Juan de Dios Hospital.[2] In 1862, troops led by General Tomás O´Horan defeated French sympathizers under Leonardo Márquez, impeding the advance of French troops. This was an important precursor to the Battle of Puebla.[3]

Economy

editSince then the area's economy has changed to the production of flowers and ornamental plants along with some commerce and industry. There have also been efforts to make the area attractive for tourists, with various festivals and other events established since the late 20th century.[2]

In 2008, the municipality set a world record for the largest chile en nogada, measuring 2.6 meters by 90cm.[8]

The city

editThe city of Atlixco is in the west of the state of Puebla at an elevation of 1,881 meters above sea level, 25 km from the state capital of Puebla.[2][4] The main economic activities of the city are agriculture and basic commerce.[2] It lies at the foot of the Cerro de San Miguel mountain, which is the main geographical and cultural landmark, marked by a small hermitage at the top dedicated to the Archangel Michael. According to local lore, a demon was entrapped in the well there, after causing problems in the community.[9][10] There are also lookout points that provide panoramic views of the city.[11]

The city centers on a main square which is Moorish in style, surrounded by restaurants and other places selling local specialties and ice cream.[2][11] Notable location on or near the square include the Casa de la Audencia, with its portal supported by Tuscan columns, the Portal Hidalgo, the old Marqués de Santa Martha House, the Botica Poblana pharmacy (founded in 1877 but taken down around 2005), the Rascon Building from the late 19th century, CADAC (an arts and trades school) and the Isaac Ochotorena House from the 18th century.[2] Another important area of the city is Colonia Cabrera, noted for its abundance of greenhouse production of flowers and ornamental plants.[3][12]

The most important churches in the city date from the 18th century, noted for their intricate "folk Baroque" facades created from stucco by indigenous craftsmen.[3][13] The La Merced Temple is all that remains of a Mercedarian monastery. Most of the church, including a decorative side door is from the 17th century, but the façade is from the 18th century. The main portal is decorated with paired columns, spiraling vines in high relief and ornamental sculptures in niches on both the upper and lower levels. The doorway itself is a lobed Moorish arch. The center of this decoration is a niche with an image of the Virgin of Mercy, who shelters Mercedarian founder Pedro Nolasco and other saints with her cloak. The interior was redone in the 19th century, but maintains a large colonial era portrait of Our Lady of Mercy by José Joaquín Magón as well as an 18th-century inlaid wood pulpit.[13] This church has a collection of paintings from the colonial period. This collection is under the care of the Adopt a Work of Art campaign working to restore many of the canvases to their original state.[9]

The Third Order Chapel is at the foot of the hill where the former Franciscan monastery is located and also has portal work of stucco.[2][13] The west facade has a classic altarpiece design in folk Baroque with cherubs and angels throughout. It contains pairs Solomonic columns with vines and fruits with two tiers of ornamental niches with saints and apostles. Above the arched doorway is a cornucopia and above this is a choir window covered by a shell arch. On either side of the window there are columns and geometric relief patterns as well as Moorish medallions. Inside there is a notable 18th-century gold leaf altarpiece called the Retablo de Reyes.[13][14]

Although the parish church called Natividad itself has a plain facade, it has an ornate addition called the Santuario del Santísimo (Most Holy Sanctuary), built in the late 1700s on the north side with a polychrome stucco facade and painted cupola. The former main portal has decorative spiral columns, which are topped by "woven" columns and bands of filigree and foliated relief around a choir window shaped like a shell. Above the facade, there is an escutcheon with a relief of the Holy Sacrament and a two-headed Habsburg eagle. On the sides of this are rampant lions and angels in while on an ocher background. The interior was redone in Neo Classical in the 19th century, with one Baroque altarpiece surviving, attributed to Luis Juárez.[13]

Other important churches include the San Agustin Church, built between 1589 and 1698,also with Baroque stucco work,[2] the La Soledad Chapel and the chapels of Santa Clara and El Carmen.[3] The San Felix Papa Church has a façade which is identical to a large sized painting possibly from the 18th century, which is found in the sacristy of the Natividad Parish Church on the main plaza.[2] It contains works from the 17th century, including a collection of apostles dressed as popes.[9]

There were a number of monasteries in the community during the colonial period, all now either destroyed or no longer active. The most notable of these is the former Franciscan monastery built on a hill in fortress fashion, walking distance from the main square. The atrium offers panoramic views of the city and the church is popular for weddings.[9] Inside there is a Baroque main altar.[2] In the 16th century, the Augustinians built a monastery under Melchor de Vargas, not for evangelization but rather to represent their order and provide services to the local criollo population. The church has two facades, with the main one on the north side. The portal of the side has Baroque decoration in stucco, as does the bell tower. Another was a convent called Las Clarisas founded in 1617.[2]

The San Juan de Dios Municipal Hospital was founded is one of the few colonial-era hospitals still running. The building is marked by an original statue of Saint Adrian fighting a lion. It is also noted for a significant painting collection, which is open to the public. Next to the hospital is a church dedicated to the Archangel Raphael.[9]

The municipal palace is facing the main square and distinguished by a facade decorated in Talavera tile.[2] Originally the city library, its inner walls contain a series of murals related to the history and culture of the municipality and the country, including its founding, history of education in Mexico, and heroes of wars of Independence and Reforma.[9]

The municipal market is one block from the main square, which also has stalls specializing in local foods.[11] Tianguis day in the city is Saturday, when streets fill with stalls selling fruits, vegetables, flowers, bread and many other staples. It is one of the largest and oldest tianguis in the state.[3]

There is one museum called Museo Obrero, located inside the Centro Vacacional IMSS Metepec, along with a cultural center located in a former textile factory.[2]

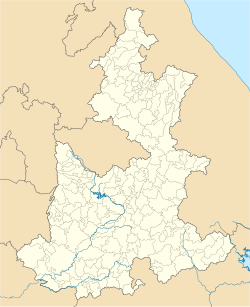

The municipality

editThe city of Atlixco is the local government for a number of other nearby communities, which form a municipality that covers an area of 229.22 km2. The municipal government consists of a president, a syndic, and twelve representatives for the various communities. Outside the seat, the main communities are San Pedro Benito Juárez, Santo Domingo Atoyatempan, San Jerónimo Coyula, La Trinidad Tepango, Axocapan, San Miguel Ayala, San Jerónimo Caleras, San Diego Acapulco, Santa Lucia Cosamaloapan and Metepec. It borders the municipalities of Tianguismanalco, Santa Isabel Cholula (municipality), Ocoyucan, Atzitzihuacán, Huaquechula, Tepeojuma, San Diego la Meza Tochimiltzingo (municipality), Puebla and Tochimilco.[2]

The main economic activities for the municipality are agriculture and livestock.[2] The Centro Vacacional Metepec is seven km northwest of the city, in a former textile factory. Today it is one of the state's most important water parks.[2]

Geography

editThe territory of the municipality is divided between the Valley of Puebla and the Atlixco Valley, both of which extend from the Sierra Nevada. The altitude varies from a low of 1,700 meters above sea level in the south to 2,500 in the northwest at the foot of the Iztaccihuatl Volcano, with an overall average altitude of 1840. The center of the territory is a valley floor that extends from north to south, with isolated mountains such as Zoapiltepec and Texistle in the southeast. Other isolated peaks include the Pochote, Tecuitlacuelo, Loma La Calera and El Charro.[2]

The municipality is located in the basin of the Nexapa River, a tributary of the Atoyac. Various streams run through the territory, which have their source at the Iztaccihuatl Volcano; however, most depending on snow melt from the volcano. The Nexcapa is one of the few that run year-round and splits the Atlixco Valley in half. Other larger ones include the Cuescomante, which passes by the seat, the Molino and the Palomas. The highest elevations at the foot of the volcanos are marked by a large number of ravines. The San Pedro Atlixco Waterfall is in this area, surrounded by pines and cedars. This area has fishing, boating, camping and more.[2][4]

Climate

editThe municipality is in the transition zone between the more temperate climates of the north of the state and the hotter climates of the south. The northwest and isolated peaks have a temperate and semi humid climate as it has the highest altitude. The center and south have a warm and semi-humid climate.[2]

| Climate data for Atlixco (1951–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.0 (87.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

39.0 (102.2) |

35.0 (95.0) |

38.0 (100.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.0 (95.0) |

33.0 (91.4) |

35.0 (95.0) |

38.0 (100.4) |

35.0 (95.0) |

31.0 (87.8) |

39.0 (102.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 24.3 (75.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.6 (83.5) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

19.8 (67.6) |

20.4 (68.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

17.3 (63.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

7.9 (46.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.5 (50.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.0 (30.2) |

1.0 (33.8) |

3.0 (37.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 9.8 (0.39) |

7.2 (0.28) |

8.0 (0.31) |

22.2 (0.87) |

74.1 (2.92) |

174.1 (6.85) |

149.0 (5.87) |

178.6 (7.03) |

161.6 (6.36) |

67.3 (2.65) |

12.0 (0.47) |

2.5 (0.10) |

866.4 (34.11) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 4.2 | 9.6 | 16.9 | 15.3 | 17.1 | 16.8 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 93.8 |

| Source: Servicio Meteorologico Nacional[15] | |||||||||||||

Flora

editMost of the valley floor area is dedicated to irrigated farming, with rainy season farming dominant in the higher elevations. The latter has contributed to extensive deforestation, cutting down pines and cedars. The only remaining wild vegetation is in small areas in the north and northeast, where these trees still exist. In small areas in the southeast, there is pastureland and scrub brush.[2]

Culture

editThe most important annual event in the municipality is known as El Huey Atlixcayotl, a Nahuatl phrase which roughly translates to "the great Atlixco tradition".[2][12] This event, started in 1965, is a reinvention of an old indigenous celebration that tradition says in the pre Hispanic period honored the god Quetzalcoatl, giving thanks for the harvest. On the last Saturday of September, the event begins with the selection of the festival queen, called the Xochicihuatl (lit. flower woman) and a dance called Las Canastas, when women dance with baskets of fireworks on their heads. The main events are on the following day, Sunday, when a parade of between 800 and 1,500 participants from Puebla's eleven regions leaves the town square to climb Cerro de San Miguel, which has a stage area with stands. The rest of the day is filled with performances by charros, bands, mojigangas, voladores and more.[3][14] These activities are in honor of the Archangel Michael, who has a small church on the mountain. In 1996 the event was named as part of the Cultural Heritage of Puebla.[2]

The Festival de la Ilusión (Festival of Joy) was started in the 1990s by two teenagers to reinforce the tradition of Three Kings' Day in Mexico, January 6. At that time, many fathers and other family members went to the United States to work, leading to foreign influences such as Santa Claus. To give January 6 precedence, the teens took a collection from local businesses to buy thousands of balloons and envelopes so that children could have a mass launch, sending their requests for toys. The fourth of January is still dedicated to this launch, but two days have been added. On January 5, a 5 km parade with floats in honor of the Three Kings is held, and on January 6 the local convention center hosts musical groups, clowns and other forms of entertainment for the city.[10][16]

The Festival de la Iluminación (Lights Festival) or Villa Iluminada (Lighted Village) begins on November 20 with large lighted figures that adorn the city's streets.[16] This event was begun in 2010, with the lights placed along a corridor of a km and half. The event draws over 500,000 visitors to the city during the 46 days it is set up from the end of November to the beginning of January. In addition to the lights the event also features amusement rides, and an exhibition of sky lanterns.[17][18]

Some of the annual events are related to Atlixco's economy. The Festival de la Flor (Flower Festival) celebrates the municipality's main economic activity of growing flowers. Starting in the second week of March, giant "carpets" are created by arranging flowers on the street. During the last two weeks of the month, large flower sculptures are created to attract visitors, along with musical events and other attractions.[16] The Feria de la Nochebuena (Poinsettia Fair) begins on November 25 and runs through the Christmas season to promote the plants of this type grown in the municipality. The Feria de la Noche Buena began in 2001 and is timed for the start of the Christmas season.[19] The Feria de la Cecina (Cecina Fair) promotes the local version of this meat, in August with artistic and cultural events.[16] The last two weeks of October are dedicated to the regional fair.[2]

La Noche de las Estrellas (Night of the Stars) occurs on the last Saturday of February, when about 5,000 people come together on the Cerro de San Miguel mountain to observe the night sky, through the telescopes of the observatory there. The event promotes the organizations courses and workshops as well as a program to provide telescopes to families.[16]

For Holy Week, the streets of the Nexatengo community are adorned with flowers, pine branches and sawdust carpets for a procession of Jesus in which 8,000 people participate in an eight km procession.[16]

The Desfile de Calaveras (Skull Parade) takes place on November 2, Day of the Dead.[16]

It is during traditional festivals that local food specialties and dress most often appear. Traditional dishes include cecina, a local variety of consome called "atlixquense", chiles en nogada, barbacoa, mole poblano, mole de panza, mole de olla, mole verde, pozole blanco, tostadas, enchiladas, pambazos, tortas, cemitas, molotes and tlacoyos.[2][20]

The most traditional dress is now seen only on certain occasions and dances. For women, this is the style of the China Poblana, or alternatively a long full flowered skirt with white blouse and rebozo. For men this consists of a shirt and pants made of undyed cotton, huaraches and a hat made of palm fronds.[2]

Economy

editThe city of Atlixco is a regional commercial, manufacturing and industrial center with textile mills, distilleries and bottling plants.[4] Traditional handcrafts also are made here and in the rest of the municipality including ceramic utensils, embroidered shirts and blouses and candles.[2]

However, the municipality is best known for its cultivation of ornamental plants, flowers and fruit trees.[11] Flowers include roses, geraniums, chrysanthemums, and Cornish mallow (Lavatera cretica).[3] All of its potted plant production is sold in Mexico, with eighty percent of the cut flowers sent abroad, mostly to the United States.[21]

The municipality ranks first in the production of roses and gladiolas and is one of the largest producers of poinsettias,[21] helping to make the state of Puebla fourth in Mexico in its production. Fifty two producers on twenty five hectares typically produce 1.5 million poinsettials per year.[19] Sales from poinsettias alone reach at least 68 million pesos for the municipality and support 800 families. Most of the plants are shipped to other Mexican states such as Veracruz, Oaxaca, Chiapas, Yucatán and Campeche.[22] The main flowers grown and sold for Day of the Dead include chrysanthemums, gladiolas and baby's breath.[23]

In addition, other crops such as wheat, corn, beans and fruits, much of which are processed locally and distributed from the city.[4]

The Fuerte avocado, second largest commercial avocado cultivar after Hass,[24] was first identified in Atlixco in the early 20th century.[25]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Puebla is declared a city of learning by UNESCO". NewsyList. 2020-09-24. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af "Atlixco". Enciclopedia de Los Municipios y Delegaciones de México Estado de Puebla. Mexico: INAFED. 2010. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Edgar Anaya (March 25, 2001). "Atlixco, Puebla: Su arquitectura surge entre flores". Monterrey, Mexico: El Norte. p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e "Atlixco". Britannica. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ He took possession of the Divisa Regajal on May 10, 1664 (S.V., B.20, fol. 123 vo)(7).

- ^ Diaz, Daniel (2024-07-04). "El Estado sale de compras en Fernando Durán". ARS Magazine (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-09-01.

- ^ TOMÁS FERNÁNDEZ DE MEDRANO CONSEJERO Y SECRETARIO DE ESTADO Y GUERRA DE LOS DUQUES DE SABOYA DIVISERO DEL SOLAR DE VALDEOSERA by D. Luis Pinillos Lafuente, divisero of Valdeosera page 29. https://cuadernosdeayala.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/CAyala-87.pdf

- ^ "Elaboran el chile en nogada más grande del mundo en Atlixco". Mexico City: Notimex. August 23, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f "Lugares de Interés" (in Spanish). Municipality of Atlixco. April 16, 2011. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ a b "Atlixco se llena de color por Día de Reyes". El Universal. Mexico City. January 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Imperdibles" (in Spanish). Municipality of Atlixco. April 16, 2011. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ a b "Recorridos" (in Spanish). Municipality of Atlixco. April 16, 2011. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Atlixco: Treasure city of the Pueblan baroque". Exploring Colonial Mexico. Espadaña Press. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ a b Ricardo Diazmunoz; Maryell Ortiz de Zarate (September 18, 2005). "Encuentros con Mexico / La gran fiesta de Atlixco". Guadalajara, Mexico: Mural. p. 3.

- ^ NORMALES CLIMATOLÓGICAS 1951-2010 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish). National Meteorological Service of Mexico. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Fiestas y Tradiciones" (in Spanish). Municipality of Atlixco. April 16, 2011. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ Erika Mejía Peniche (November 18, 2013). "Atlixco pondrá en marcha la Villa Iluminada". Mexico City: E-consulta. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ Ricardo Camacho Corripio (November 18, 2013). "Atlixco realizará la "Villa Iluminada"". Mexico City: SDP Noticias. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ a b Erika Mejía Peniche (November 12, 2013). "Durante feria, Atlixco venderá al menos 500 mil plantas de Noche Buena". Mexico City: E-consulta. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ "Gastronomía de Atlixco" (in Spanish). Municipality of Atlixco. April 16, 2011. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ a b "Es Atlixco líder en producción de rosas y gladiolas". Mexico City: Notimex. July 1, 2009.

- ^ Erika Mejía Peniche (November 19, 2013). "Flor de noche buena, industria de 68 mdp al año". Mexico City: E-consulta. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ Clara Ramirez (November 5, 2004). "Crece produccion de flores en Atlixco". Mexico City: Reforma. p. 24.

- ^ "Fuerte Avocado Trees - Louie's Nursery & Garden Center - Riverside CA". Louie's Nursery. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ Rounds, Marvin B. (1946). California Avocado Society 1946 Yearbook (PDF). California Avocado Society. pp. 54–56.