Australopithecus garhi is a species of australopithecine from the Bouri Formation in the Afar Region of Ethiopia 2.6–2.5 million years ago (mya) during the Early Pleistocene. The first remains were described in 1999 based on several skeletal elements uncovered in the three years preceding. A. garhi was originally considered to have been a direct ancestor to Homo and the human line, but is now thought to have been an offshoot. Like other australopithecines, A. garhi had a brain volume of 450 cc (27 cu in); a jaw which jutted out (prognathism); relatively large molars and premolars; adaptations for both walking on two legs (bipedalism) and grasping while climbing (arboreality); and it is possible that, though unclear if, males were larger than females (exhibited sexual dimorphism). One individual, presumed female based on size, may have been 140 cm (4 ft 7 in) tall.

| Australopithecus garhi Temporal range: Gelasian, 2.6–2.5 Ma

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstruction of the skull at the National Museum of Ethiopia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | †Australopithecus |

| Species: | †A. garhi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Australopithecus garhi Asfaw et al., 1997

| |

A. garhi is the first pre-Homo hominin postulated to have manufactured tools—using them in butchering—and may be counted among a growing body of evidence for pre-Homo stone tool industries (the ability to manufacture tools was previously believed to have separated Homo from predecessors.) A. garhi possibly produced the Oldowan industry which was previously considered to have been invented by the later H. habilis, though this may have instead been produced by contemporary Homo.

Anatomy

editLike other australopithecines, A. garhi had a brain volume of about 450 cc (27 cu in), a sagittal crest running along the midline of the skull, and a prognathic jaw (the jaw jutted out). Relatively, the postcanine teeth, the molars and premolars, are massive (post-canine megadontia), similar to or greater than those of other australopithecines and of the large-toothed Paranthropus robustus.[1]

Like the earlier A. afarensis from the same region, A. garhi had a humanlike humerus to femur ratio, and an apelike brachial index (lower to upper arm ratio) as well as curved phalanges of the hand.[1] This is generally interpreted as adaptations for both walking on two legs (habitual bipedalism) as well as for grasping while climbing in trees (arboreality).[2]

The BOU-VP-35/1 humerus specimen is notably larger than the humerus of the BOU-VP-12/1 specimen, which could potentially indicate size-specific sexual dimorphism with males larger than females to a similar degree to what is postulated in A. afarensis, but it is unclear if this does not represent normal size variation of the same sex as this is based on only two specimens. Nonetheless, on the basis of size, BOU-VP-12/130 is considered male and BOU-VP-17/1 female. Contemporary hominins from Kenya are about the same size as A. garhi.[1] BOU-VP-17/1 may have been about 140 cm (4 ft 7 in) tall.[3]

Australopithecus are thought to have had fast, apelike growth rates, lacking an extended childhood typical of modern humans. However, the legs of A. garhi are elongated, unlike those of other Australopithecus, and, in humans, elongated limbs develop during the delayed adolescent growth spurt. This could mean that A. garhi, compared to other Australopithecus, either had a slower overall growth rate, or a more rapid leg growth rate.[2]

Taxonomy

editThe Ethiopian Australopithecus garhi was first described in 1999 by palaeoanthropologists Berhane Asfaw, Tim D. White, Owen Lovejoy, Bruce Latimer, Scott Simpson, and Gen Suwa based on fossils discovered in the Hatayae Beds of the Bouri Formation in Middle Awash, Afar Region, Ethiopia. The first hominin remains were discovered here in 1990—a partial parietal bone (GAM-VP-1/2), left jawbone (GAM-VP-1/1), and left humerus (MAT-VP-1/1)—which are unassignable to a specific genus. The first identifiable Australopithecus fossils–an adult ulna (BOU-VP-11/1)–were found on 17 November 1996 by T. Assebework. A partial skeleton (BOU-VP-12/1) was discovered 13 days later by White, comprising a mostly complete left femur, right humerus, radius, and ulna, and a partial fibula, foot, and jawbone. The holotype specimen, a partial skull (BOU-VP-12/130), was discovered on 20 November 1997 by Ethiopian palaeoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie. More skull fragments (BOU-VP-12/87) were recovered 50 m (160 ft) south of BOU-VP-12/1. On 17 November 1997, French palaeoanthropologist Alban Defleur discovered a complete mandible (BOU-VP-17/1) about 9 km (5.6 mi) north in the Esa Dibo locality of the formation, and American palaeoanthropologist David DeGusta discovered a humerus (BOU-VP-35/1) 1 km (0.62 mi) north of BOU-VP-17/1. However, BOU-VP-11, -12, and -35 cannot conclusively be attributed to A. garhi.[1]

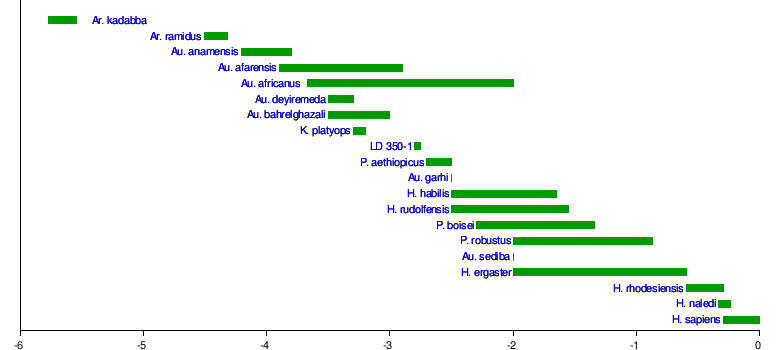

The remains are dated to about 2.5 million years ago (mya) based on argon–argon dating. When they were discovered, human evolution was obscured due to a paucity of remains from 3 to 2 mya, with the only hominins from this timespan being identified from South Africa (A. africanus) and Lake Turkana, Kenya (Paranthropus aethiopicus). Likewise, the classification of australopithecines and pre-Homo erectus hominins has been the subject of much debate. The original describers considered A. garhi to be a descendant of the earlier A. afarensis which inhabited the same region, based mainly on dental similarities. Though they assigned the species to Australopithecus, the original describers believed it could represent an ancestor to Homo, which, if the case, would possibly lead to reclassification as H. garhi. Because the characteristics of A. garhi are unexpected for a human ancestor at this stage, the specific name, garhi, means "surprise" in the local Afar language.[1][3] In 1999, American palaeoanthropologists David Strait and Frederick E. Grine concluded that A. garhi was instead an offshoot of the human line instead of an ancestor because A. garhi and Homo share no synapomorphies (traits unique to only them).[4][5] In 2015, Homo was recorded from 2.8 mya, much earlier than A. garhi.[6]

Palaeoecology

editThe large teeth of Australopithecus species have historically been interpreted as having been adaptations for a diet of hard foods, but the durable teeth may instead have only served an important function during leaner times for harder fallback foods. That is, dental anatomy may not accurately portray normal Australopithecus diet, rather abnormal diet during times of famine.[7]

Though it was not found with any tools, mammalian bones associated with the A. garhi remains exhibit cut and percussion marks made from stone tools: the left mandible of an alcelaphine bovid with three successive, unambiguous cut marks presumably made while removing the tongue; a bovid tibia with cut marks, chop marks, and impact scars from a hammerstone, possibly inflicted to harvest the bone marrow; and a Hipparion (a horse) femur with cut marks consistent with dismemberment and filleting. As to why stone tools were not present, because the Hatayae locality was likely a featureless, grassy lake margin with so few raw materials for making stone tools, it is possible these hominins were creating and carrying tools some ways with them to butchering sites, intending to use them many times before discarding. It was previously believed that only Homo could manufacture tools;[8][3] but it is also possible that the butcherers were not manufacturing tools and simply used naturally sharp rocks.[9]

At the nearby Gona site, where there is an abundance of raw materials, several Oldowan tools (an industry previously believed to have been invented by H. habilis) were recovered from 1992 to 1994. The tools date to around 2.6–2.5 mya, the oldest evidence of manufacturing at the time, and since A. garhi was the only species identified in the vicinity at the time, this species was the best candidate for authorship.[10][11] However, in 2015, the earliest remains of Homo, LD 350-1, were discovered in Ledi-Geraru, also in the Afar Region, dating to 2.8–2.75 mya.[6] More stone tools were found in 2019 dating to about 2.6 mya in Ledi-Geraru, predating the Gona artifacts, and these may be attributed to Homo; the invention of sharp-edged Oldowan tools could actually be due to specific adaptations characteristic of Homo.[12] Nonetheless, other australopithecines have been associated with stone tool manufacturing, such as the 2010 discovery of cut marks dating to 3.4 mya attributed to A. afarensis,[9] and the 2015 discovery of the Lomekwi culture from Lake Turkana dating to 3.3 mya possibly attributed to Kenyanthropus.[13]

|

See also

edit- African archaeology – Archaeology conducted in Africa

- Ardipithecus ramidus – Extinct hominin from Early Pliocene Ethiopia

- Australopithecus africanus – Extinct hominid from South Africa

- Australopithecus anamensis – Extinct hominin from Pliocene east Africa

- Australopithecus sediba – Two-million-year-old hominin from the Cradle of Humankind

- Homo gautengensis – Name proposed for an extinct species of hominin from South Africa

- Homo habilis – Archaic human species from 2.8 to 1.65 mya

- Homo rudolfensis – Extinct hominin from the Early Pleistocene of East Africa

- Kenyanthropus – Oldest-known tool-making hominin

- List of human evolution fossils

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Asfaw, B; White, T; Lovejoy, O; Latimer, B; Simpson, S; Suwa, G (1999). "Australopithecus garhi: a new species of early hominid from Ethiopia". Science. 284 (5414): 629–635. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..629A. doi:10.1126/science.284.5414.629. PMID 10213683.

- ^ a b Harmon, E. H. (2013). "Age and Sex Differences in the Locomotor Skeleton of Australopithecus". The Paleobiology of Australopithecus. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. Springer Science and Business Media. pp. 263–272. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5919-0_18. ISBN 978-94-007-5918-3.

- ^ a b c Culotta, E. (1999). "A new human ancestor?". Science. 284 (5414): 572–573. doi:10.1126/science.284.5414.572. PMID 10328732. S2CID 7042848.

- ^ Strait, D. S.; Grine, F. E. (1999). "Cladistics and Early Hominid Phylogeny". Science. 285 (5431): 1210–1. doi:10.1126/science.285.5431.1209c. PMID 10484729. S2CID 45225047.

- ^ Strait, D. S. (2001). "The systematics of Australopithecus garhi". Ludus Vitalis. 9 (15): 109–135.

- ^ a b Villmoare, B.; Kimbel, W. H.; Seyoum, C.; et al. (2015). "Early Homo at 2.8 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1352–1355. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1352V. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1343. PMID 25739410.

- ^ Scott, J. E.; McAbee, K. R.; Eastman, M. M.; Ravosa, M. J. (2014). "Experimental perspective on fallback foods and dietary adaptations in early hominins". Biology Letters. 10 (1): 20130789. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2013.0789. PMC 3917327. PMID 24402713.

- ^ De Heinzelin, J.; Clark, J. D.; White, T. D.; Hart, W.; Renne, P.; Woldegabriel, G.; Beyene, Y.; Vrba, E. (1999). "Environment and behavior of 2.5-million-year-old Bouri hominids". Science. 284 (5414): 625–629. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..625D. doi:10.1126/science.284.5414.625. PMID 10213682.

- ^ a b McPherron, S. P.; Alemseged, Z.; Marean, C. W.; et al. (2010). "Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia". Nature. 466 (7308): 857–860. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..857M. doi:10.1038/nature09248. PMID 20703305. S2CID 4356816.

- ^ Semaw, S.; Renne, P.; Harris, J. W. K. (1997). "2.5-million-year-old stone tools from Gona, Ethiopia". Nature. 385 (6614): 333–336. Bibcode:1997Natur.385..333S. doi:10.1038/385333a0. PMID 9002516. S2CID 4331652.

- ^ Semaw, S.; Rogers, M. J.; Quade, J.; et al. (2003). "2.6-Million-year-old stone tools and associated bones from OGS-6 and OGS-7, Gona, Afar, Ethiopia". Journal of Human Evolution. 45 (2): 169–177. doi:10.1016/s0047-2484(03)00093-9. PMID 14529651.

- ^ Braun, D. R.; Aldeias, V.; Archer, W.; et al. (2019). "Earliest known Oldowan artifacts at >2.58 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Ethiopia, highlight early technological diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (24): 11712–11717. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11611712B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1820177116. PMC 6575601. PMID 31160451.

- ^ Harmand, S.; Lewis, J. E.; Feibel, C. S.; et al. (2015). "3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 521 (7552): 310–315. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..310H. doi:10.1038/nature14464. PMID 25993961. S2CID 1207285.

External links

edit- Reconstruction by Viktor Deak

- "Australopithecus garhi". The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- "Australopithecus garhi". ArchaelogyInfo. Archived from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

- "The Earliest Human Ancestors: New Finds, New Interpretations". Science in Africa. 2001. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. Retrieved March 1, 2011.