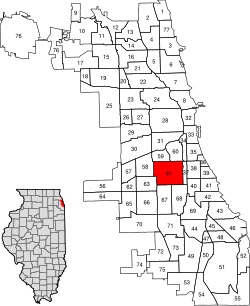

New City is one of Chicago's 77 official community areas, located on the southwest side of the city in the South Side district. It contains the neighborhoods of Canaryville and Back of the Yards.

New City

Back of the Yards/Canaryville | |

|---|---|

| Community Area 61—New City | |

Union Stock Yard Gate at Exchange Ave. | |

Location within the city of Chicago | |

| Coordinates: 41°48.6′N 87°39.6′W / 41.8100°N 87.6600°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Cook |

| City | Chicago |

| Neighborhoods | List

|

| Area | |

• Total | 4.86 sq mi (12.59 km2) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

• Total | 43,628 |

| • Density | 9,000/sq mi (3,500/km2) |

| Demographics 2020[1] | |

| • White | 12.4% |

| • Black | 23.1% |

| • Hispanic | 61.8% |

| • Asian | 1.9% |

| • Other | 0.8% |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code | part of 60609 |

| Median income 2020[1] | $35,396 |

| Source: U.S. Census, Record Information Services | |

The area was home to the famous Union Stock Yards from 1865 until it closed in 1971, and the International Amphitheatre from 1934 until it was demolished in 1999.

Neighborhoods

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 87,103 | — | |

| 1940 | 80,725 | −7.3% | |

| 1950 | 75,917 | −6.0% | |

| 1960 | 67,428 | −11.2% | |

| 1970 | 60,747 | −9.9% | |

| 1980 | 55,860 | −8.0% | |

| 1990 | 53,226 | −4.7% | |

| 2000 | 51,721 | −2.8% | |

| 2010 | 44,377 | −14.2% | |

| 2020 | 43,628 | −1.7% | |

| [1][2] | |||

Back of the Yards

editBack of the Yards is an industrial and residential neighborhood so named because it was near the former Union Stock Yards, which employed thousands of European immigrants in the early 20th century. Life in this neighborhood was explored in Upton Sinclair's 1906 novel The Jungle. The area was formerly part of the town of Lake until it was annexed by Chicago in 1889. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the area was occupied largely by Eastern European immigrants and their descendants, who were predominantly ethnic Lithuanian, Bohemian, Moravian, and Slovak.[3]

In 1939, the activist Saul Alinsky and the local park director Joseph Meegan organized the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council, where Alinsky first developed the method of community organizing. The prerequisites of this successful attempt to bring together community leaders from different national Catholic churches, business, and labor were the Great Depression and the labor organizing work of the Packinghouse Workers Organizing Committee, a member of the CIO led in Chicago by Herb March. This work led to his founding the Industrial Areas Foundation in 1940, which later trained community organizers.[4]

Jane Jacobs, in her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, cites the Back of the Yards as an area able to "unslum" in the 1960s, due to a beneficial set of circumstances. This included a stabilized community base with skilled members who were willing to trade work to upgrade housing, as well as active and well-led local social and political organizations. Jacobs often cited the Back of the Yards as a model for other depressed neighborhoods to follow to upgrade their communities.[5]

Some time after the 1970s, when the stockyard operations closed and the number of nearby jobs decreased, many people left to move to newer housing and work in the suburbs. The population of the neighborhood gradually reflected a new wave of settlement, predominantly Mexican-American.

Canaryville

editThe Canaryville neighborhood is one of the oldest neighborhoods in Chicago, and borders the Bridgeport neighborhood. According to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, the neighborhood extends from Pershing Road to 49th Street and centers on Halsted Street. The area's residents experienced the development, and then decline, of the meat packing industry, when Chicago was, in the words of Carl Sandburg, "hog butcher for the world". Many of its residents found other work in the post–World War II years.

Historically, Canaryville was a largely Irish American neighborhood, starting Irish immigrants escaping the Great Famine in the mid-19th century. They were deeply entrenched in the neighborhood, considering it their territory, and attempted to defend it against later arrivals of all races –including non-Irish White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian people. Its Irish gangs were active in attacks on Black people in the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. Since the late 20th century, Latin American (predominantly Mexican) immigrants and their descendants have moved into the area.[6] Canaryville is now largely both Irish and Mexican.

Canaryville's name may refer to the sparrows who fed in the stockyards and railroad cars in the late 1800s. The name may also refer to white youth gangs in the neighborhood from the early 1900s, who were known as "wild canaries".[6]

Politics

editThe New City community area supported the Democratic Party in the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections. In 2016, New City cast 8,897 votes for Hillary Clinton and 1,331 votes for Donald Trump (84.40% to 12.63%).[7] In 2012, New City cast 9,053 votes for Barack Obama and 1,009 votes for Mitt Romney (89.36% to 9.96%).[8]

Notable residents

edit- Ted Kaczynski, the "Unabomber" spent the first years of his life in Back of the Yards.[9]

References

edit- ^ a b c d "Community Data Snapshot - New City" (PDF). cmap.illinois.gov. MetroPulse. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ Paral, Rob. "Chicago Community Areas Historical Data". Archived from the original on March 18, 2013. Retrieved September 3, 2012.

- ^ "Back of the Yards", Encyclopedia of Chicago

- ^ Sanford D. Horwitt: Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky. His Life and Legacy. Vintage Books, New York 1992, pp. 56–87.

- ^ Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961.

- ^ a b "Canaryville", Encyclopedia of Chicago

- ^ Ali, Tanveer (November 9, 2016). "How Every Chicago Neighborhood Voted In The 2016 Presidential Election". DNAInfo. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Ali, Tanveer (November 9, 2012). "How Every Chicago Neighborhood Voted In The 2012 Presidential Election". DNAInfo. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ "Ted Kaczynski, Chicago-born 'Unabomber' responsible for 16 bombings, died by suicide in prison: sources". www.chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 28, 2024.

External links

edit- Official City of Chicago New City Community Map

- Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (oldest community organization in the United States, founded by Alinsky in 1939)