The Baháʼí Faith was discussed in the writings of various Western intellectuals and scholars during the lifetime of Baháʼu'lláh. His son and successor, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, travelled to France and Great Britain and gave talks to audiences there. There is a Baháʼí House of Worship in Langenhain, Germany, which was completed in 1964. The Association of Religion Data Archives reported national Baháʼí populations ranging from hundreds to over 35,000 in 2005. The European Union and several European countries have condemned the persecution of Baháʼís in Iran.

Earliest connections

editThe Baháʼí Faith originated in Asia, in Iran (Persia) and before there were any Baháʼís in Europe, the first newspaper reference to the religious movement began with coverage of the Báb which occurred in The Times on 1 November 1845, only a little over a year after the Báb first started his mission.[1] Similarly the Russian Empire took a notice of events. The religion had strong connections with Azerbaijan during the Russian rule in Azerbaijan. Among the most notable facts is a woman of Azerbaijani background who would play a central role in the religion of the Báb, viewed by Bahá´ís as the direct predecessor of the Baháʼí Faith – she would be later named Tahirih, though her story would be in the context of Persia.[2] She was among the Letters of the Living of the Báb.

In 1847, the Russian ambassador to Tehran, Prince Dimitri Ivanovich Dolgorukov became aware of the claims of the Báb and seeing the fleeing of Bábís across the border requested that the Báb, then imprisoned at Maku, be moved elsewhere; he also condemned the massacres of Iranian religionists.[3][4] Dolgorukov wrote some memoirs later in life but much of it has been shown to be a forgery. But his dispatches show that he was afraid of the movement spreading into the Caucasus.[5][6]

In 1852, after a failed assassination attempt against the Shah of Persia for which the entire Bábí community was blamed, many Bábís, including Baháʼu'lláh, who had no role in the attempt and later severely condemned it, were arrested in a sweep.[7] News coverage of the events reached beyond London and Paris to Dutch newspapers.[8] When Baháʼu'lláh was jailed by the Shah, his family went to Mírzá Majid Ahi who was married to a sister of Baháʼu'lláh, and was working as the secretary to the Russian Legation in Tehran. Baháʼu'lláh's family asked Mírzá Majid to go to Dolgorukov and ask him to intercede on behalf of Baháʼu'lláh, and Dolgorukov agreed however this assistance was short lived. In addition, Baháʼu'lláh refused the offer of exile in Russia.[9] Similarly the British consul-general of Baghdad offered him British citizenship and offered to arrange for a residence for him in India or any place he wished. Baháʼu'lláh refused the offer.[10]

After being further banished from Baghdad, Baháʼu'lláh wrote a specific letter or "tablet" addressed to Queen Victoria commenting favorably on the British parliamentary system and commending the Queen for the fact that her government had ended slavery in the British Empire.[11] She, in response to the tablet, is reported to have said, though the original record is lost, that "If this is of God, it will endure; if not, it can do no harm."[12][13] Though in no way espousing his beliefs, Baháʼís know Arthur de Gobineau as the person who wrote the first and most influential account of the movement, displaying a both accurate and inaccurate knowledge, of its history in Religions et philosophies dans l'Asie centrale in 1865 followed almost simultaneously in western press by Alexander Kasimovich Kazembek as a series of articles entitled Bab et les Babis in the Journal asiatique.[14][15]

In 1879, on the developing trade relations initiated by some Dutch businessmen, Dutchman Johan Colligan entered into partnership with two Baháʼís, Haji Siyyid Muhammad-Hasan and Haji Siyyid Muhammad-Husayn, who were known later as the King and Beloved of Martyrs. These two Baháʼís were arrested and executed because the Imám-Jum'ih at the time owed them a large sum of money for business relations and instead of paying them raised up a mob that would confiscate their property.[16] Their execution was committed despite Johan Colligan's testifying to their innocence.

In addition to newspaper coverage and diplomatic communications a growing scholarly interest reached the point that in April 1890 Edward G. Browne of Cambridge University was granted four interviews with Baháʼu'lláh after he had arrived in the area of Akka and left the only detailed description by a Westerner.[17]

The developing portrait of the Babis/Baháʼís from accounts of businessmen and travelers communicated to the Dutch public, for example, was different than the early reports of isolationist rebels with poor morals, and was of being prone to engage with foreigners, being monogamous, and seeking out civil authorities for protection from Muslim mobs.[18] However the French were still occupied much more with the Báb's dramatic life and the persecution his religion and life were subject to. French writer Henri Antoine Jules-Bois said that: "among the littérateurs of my generation, in the Paris of 1890, the martyrdom of the Báb was still as fresh a topic as had been the first news of his death. We wrote poems about him. Sarah Bernhardt entreated Catulle Mendès for a play on the theme of this historic tragedy."[19] The French writer A. de Saint-Quentin also mentioned the religion in a book published in 1891.[19] For all the attention, little penetrated to understanding the religion itself.[20]

Early development

editʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West

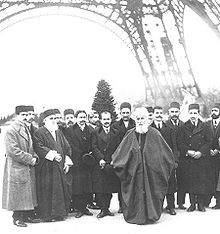

editIn 1910, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, then head of the Baháʼí Faith, embarked on a three-year journey to Egypt, Europe, and North America, spreading the Baháʼí message.[21]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's first European trip spanned from August to December 1911, at which time he returned to Egypt. During his first European trip he visited Lake Geneva on the border of France and Switzerland, Great Britain and Paris, France. The purpose of these trips was to support the Baháʼí communities in the West and to further spread his father's teachings,[22] after sending representatives and a letter to the First Universal Races Congress in July.[23][24]

His first touch on European soil was in Marseille, France where he was met by one of the earliest French Baháʼís - Hippolyte Dreyfus.[25] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in France for a few days before going to Vevey in Switzerland. While in Thonon-les-Bains, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá met Mass'oud Mirza Zell-e Soltan, who had asked to meet ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Soltan, who had ordered the execution of King and Beloved of martyrs, was the eldest grandson of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar who had ordered the execution of the Báb himself. Juliet Thompson, an American Baháʼí who had also come to visit ʻAbdu'l-Bahá while still in this early phase of his journeys, recorded comments of Dreyfus who heard Soltan's stammering apology for past wrongs. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá embraced him and invited his sons to lunch.[26] Thus Bahram Mírzá Sardar Mass'oud and Akbar Mass'oud, another grandson of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, met with the Baháʼís, and apparently Akbar Mass'oud was greatly affected by meeting ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[27] From then he went to Great Britain.

During his travels, he visited England in the autumn of 1911. On 10 September he made his first public appearance before an audience at the City Temple, London, with the English translation spoken by Wellesley Tudor Pole.[28][29]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in Liverpool on 13 December,[30] and over the next six months he visited Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, and Germany before finally returning to Egypt on 12 June 1913.[22]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Tablets of the Divine Plan

editIn the history of the Baháʼí Faith the first mention of many European countries is in the twentieth century. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, the son of the founder of the religion, wrote a series of letters, or tablets, to the followers of the religion in the United States in 1916-1917; these letters were compiled together in the book titled Tablets of the Divine Plan. The seventh of the tablets was the first to mention several countries in Europe including beyond where ʻAbdu'l-Bahá had visited in 1911-12. Written on 11 April 1916, it was delayed in being presented in the United States until 1919 – after the end of World War I and the Spanish flu. The seventh tablet was translated and presented by Mirza Ahmad Sohrab on 4 April 1919, and published in Star of the West magazine on 12 December 1919.[31]

"In brief, this world-consuming war has set such a conflagration to the hearts that no word can describe it. In all the countries of the world the longing for universal peace is taking possession of the consciousness of men. There is not a soul who does not yearn for concord and peace. A most wonderful state of receptivity is being realized.… Therefore, O ye believers of God! Show ye an effort and after this war spread ye the synopsis of the divine teachings in the British Isles, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia, Italy, Spain, Belgium, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Holland, Portugal, Rumania, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Greece, Andorra, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, San Marino, Balearic Isles, Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, Crete, Malta, Iceland, Faroe Islands, Shetland Islands, Hebrides and Orkney Islands."[32]

Succeeding development of the religion in the 1920s after World War I under Shoghi Effendi, head of the religion after ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, included development of the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assemblies and National organizations.[33] In 1923 the first Baháʼí National Spiritual Assemblies were elected "where conditions are favorable and the number of the friends has grown and reached a considerable size".[34] Along with India and the British Isles, the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Germany and Austria was first elected in that year.[35] A 1925 list of "leading local Baháʼí Centres" of Europe listed organized communities of Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK - the largest being in Germany.[36] However much of the organization of the Baháʼís was lost in World War II. For example, during the early Nazi period Baháʼís had general freedom; May Maxwell, wife of William Sutherland Maxwell, was still able to travel through Germany in 1936,[37] though the plaque commemorating ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's visit had been taken down.[38] By 1937 however, Heinrich Himmler signed an order disbanding the Baháʼí Faith's institutions in Germany[2] because of its 'international and pacifist tendencies'.[39] In 1939 and in 1942 there were sweeping arrests of former members of the National Spiritual Assembly. In May 1944 there was a public trial in Darmstadt at which Dr. Hermann Grossmann was allowed to defend the character of the religion but the Baháʼís were instead heavily fined and its institutions continued to be disbanded. However, for this service and others, Grossmann was ranked as the third of the three believers who decisively influenced the German Baháʼís.[40] To the east in 1938 "monstrous accusations"[39] accusing Baháʼís of being 'closely linked with the leaders of Trotskyite-Bukharinist and Dashnak-Musavat bands'.[39] Following this numerous arrests and Soviet government policy of oppression of religion was established. Baháʼís, strictly adhering to their principle of obedience to legal government, abandoned its administration and properties[41] but Baháʼís across the Soviet Union were sent to prisons and camps or sent as refugees to other countries anyway.[39][42] Baháʼí communities in 38 cities across Soviet territories ceased to exist.[43]

(Re-)Establishment of the community

editStarting in 1946 Shoghi Effendi drew up plans for the American (US and Canada) Baháʼí community to send pioneers to Europe; the Baháʼís set up a European Teaching Committee chaired by Edna True.[44] At a follow-up conference in Stockholm in August 1953, Hand of the Cause Dorothy Beecher Baker asked for a Baháʼí to settle in Europe. By 1953 many had. Soon many national assemblies reformed. Baháʼís had managed to re-enter various countries of the Eastern Bloc to a limited degree.[4]

Meanwhile, in Turkey by the late 1950s Baháʼí communities existed across many of the cities and towns Baháʼu'lláh passed through on his passage through the country.[45] In 1959 the Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly of Turkey was formed with the help of ʻAlí-Akbar Furútan, a Hand of the Cause — an individual considered to have achieved a distinguished rank in service to the religion.[40][46] However repeating the pattern of arrests in the 20s and 30s, in 1959 there was a mass arrest of the local assembly of Ankara.[45] Because of the religious dimension of the situation the court requested three experts in comparative religion to give their opinion: two of the three experts supported viewing the Baháʼí Faith as an independent religion, and one claimed that it was a sect of Islam. After this report, the court appointed three respected religious scholars to review all aspects of the question and advise the court of their views. All three of these scholars agreed that the religion was independent on 17 January 1961. However the judges chose to disregard these findings and on 15 July 1961 declared that the Baháʼí Faith was a forbidden sect.

In 1962 in "Religion in the Soviet Union", Walter Kolarz notes:

"Islam…is attacked by the communists because it is 'reactionary', encourages nationalist narrowmindness and obstructs the education and emancipation of women. Baha'iism(sic) has incurred communist displeasure for exactly the opposite reasons. It is dangerous to Communism because of its broadmindness, its tolerance, its international outlook, the attention it pays to women's education and its insistence on equality of the sexes. All this contradicts the communist thesis about the backwardness of all religions."[39]

House of Worship

editThe construction of the Baháʼí House of Worship in Langenhain near Frankfurt, began in 1952.[2] Hand of the Cause Amelia Collins represented the Baháʼí International Community at the groundbreaking 20 November 1960. Designated as the "Mother Temple of Europe",[47] it was dedicated in 1964 by Hand of the Cause Ruhiyyih Khanum, representing the first elected Universal House of Justice.[48]

First Baháʼí World Congress

editIn 1963 the British community hosted the first Baháʼí World Congress. It was held in the Royal Albert Hall and chaired by Hand of the Cause Enoch Olinga, where approximately 6,000 Baháʼís from around the world gathered.[49][50] It was called to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the declaration of Baháʼu'lláh, and announce and present the election of the first members of the Universal House of Justice with the participation of over 50 National Spiritual Assemblies' members from around the world.

Rebirth and restriction in the East

editWhile the religion grew in Western Europe, the Universal House of Justice, the head of the religion since 1963, then recognized small Baháʼí presence across the USSR of about 200 Baháʼís.[3] As Perestroyka approached, the Baháʼís began to organize and get in contact with each other.

Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union Baháʼís in several cities were able to gather and organize. In this brief time ʻAlí-Akbar Furútan was able to return in 1990 as the guest of honor at the election of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of the Soviet Union.[51] From 1990 to 1997 Baháʼís had operated in some freedom, growing to 20 groups of Baháʼís registered with the federal government, but the Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations passed in 1997 is generally seen as unfriendly to minority religions though it hasn't frozen further registrations.[52] Conditions are generally similar or worse in other Russian block countries. See their respective entries below.

Modern community

editSince its inception the religion has had involvement in socio-economic development beginning by giving greater freedom to women,[53] promulgating the promotion of female education as a priority concern,[54] and that involvement was given practical expression by creating schools, agricultural coops, and clinics.[53] The religion entered a new phase of activity when a message of the Universal House of Justice dated 20 October 1983 was released.[55] Baháʼís were urged to seek out ways, compatible with the Baháʼí teachings, in which they could become involved in the social and economic development of the communities in which they lived. Worldwide in 1979, there were 129 officially recognized Baháʼí socio-economic development projects. By 1987, the number of officially recognized development projects had increased to 1482. In the 1990s British Baháʼís began involvement in Agenda 21 activities in the UK.[56] An estimated 500,000 people visited the Baháʼí pavilion at the Hanover Germany Expo 2000. The 170 square-meter Baháʼí exhibit, hosted by the Baháʼí International Community and the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Germany, featured development projects in Colombia, Kenya and Eastern Europe that illustrated the importance of grassroots capacity-building, the advancement of women, and moral and spiritual values in the process of social and economic development.[57] In 2002 the director of the Ernst Lange-Institute for Ecumenical Studies held a meeting under the auspices of the German Federal Environment Ministry titled "Orientation dialogue of religions represented in Germany on environmental politics with reference to the climate issue" for the interfaith community including the Baháʼís.[58] In 2004 the Swedish Baháʼí community began to support the Barli Development Institute for Rural Women in India.[59] In 2005 former German federal Minister of the Interior, Otto Schily, praised the contributions of German Baháʼís to the social stability of the country, noting "It is not enough to make a declaration of belief. It is important to live according to the basic values of our constitutional state, to defend them and make them secure in the face of all opposition. The members of the Baháʼí Faith do this because of their faith and the way they see themselves."[60] However the Baháʼís have been excluded from other dialogues on religious issues.[61]

Conferences of youth across Nordic countries began to happen[62][63] as well as short term "Summer Schools" as a concept of Baháʼí schools for example 2009, the Portugal community hosted one for over 200 participants from all 5 continents, and counted with Ali Nakhjavani and Violette Nakhjavani, as well as Glenford Mitchell, as main speakers.[64]

Baháʼís from much of Europe were among the more than 4,600 people who gathered in Frankfurt for the largest ever Baháʼí conference in Germany in February 2009 to that date.[65]

According to the 2005 Association of Religion Data Archives data populations in European countries range from hundreds to over 35,000[66] and the many European governments and the EU as a whole have been alarmed at the treatment of Baháʼís in modern Iran.[67]

Actions on the persecution of Baháʼís

editIn February 2009 two open letters were published with lists including British citizens registering their opposition to the trial of Baháʼí leaders in Iran. The first was when some British were among the two hundred and sixty seven non-Baháʼí Iranian academics, writers, artists, journalists and activists from some 21 countries including Iran signed an open letter of apology posted to Iranian.com and stating they were "ashamed" and pledging their support for achieving the rights detailed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights for the Baháʼís in Iran.[68] The second letter a few weeks later was when entertainers David Baddiel, Bill Bailey, Morwenna Banks, Sanjeev Bhaskar, Jo Brand, Russell Brand, Rob Brydon, Jimmy Carr, Jack Dee, Omid Djalili, Sean Lock, Lee Mack, Alexei Sayle, Meera Syal, and Mark Thomas said in an open letter printed in The Times of London of the Baháʼí leaders to be on trial in Iran:

"In reality, their only 'crime', which the current regime finds intolerable, is that they hold a religious belief that is different from the majority…. We register our solidarity with all those in Iran who are being persecuted for promoting the best development of society …(and) with the governments, human rights organisations and people of goodwill throughout the world who have so far raised their voices calling for a fair trial, if not the complete release of the Bahaʼi leaders in Iran."[69]

In between the open letters, on the 16th, British Foreign Office Minister Bill Rammell expressed concern over the trial.[70] Hungarian Otto von Habsburg remembered in an interview that it was worth raising up his voice in the European Parliament for the human rights of the Baháʼís in Iran.[71] There were two speeches in the Hungarian Parliament - one in 2009 and one in 2010.[72] In a campaign to show support for victims of human rights abuses in Iran well-known Hungarian personalities posted video messages including Kinga Göncz, a member of the European Parliament and former Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs and Márta Sebestyén, a UNESCO Artist for Peace.[73] See also Statements about the persecution of Baháʼís

By country

editCentral Europe

editGermany

editThough mentioned in the Baháʼí literature in the 19th century, the Baháʼí Faith in Germany begins in the early 20th century when two emigrants to the United States returned on prolonged visits to Germany bringing their newfound religion. The first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly was established following the conversion of enough individuals to elect one in 1908.[74] After the visit of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá,[22] then head of the religion, and the establishing of many further assemblies across Germany despite the difficulties of World War I, elections were called for the first Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly in 1923.[34] Banned for a time by the Nazi government and then in East Germany the religion re-organized and was soon given the task of building the first Baháʼí House of Worship for Europe.[2] After German reunification the community multiplied its interests across a wide range of concerns earning the praise of German politicians. There are an estimated 5,000–6,000 Baháʼís in Germany.[75]

Hungary

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Hungary started in various mentions of the religion in the 19th century followed by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's trip to Hungary in 1913 when Hungary's first Baháʼí joined the religion.[76] The community suffered from WWII and communist rule until the 1980s.[77] The National Assembly was elected in 1992 and growth since then places 2002 estimates by Baháʼís at between 1100 and 1200 Baháʼís in Hungary, many are Roma.[78] However, according to the 2005 Association of Religion Data Archives data there are close to some 290.[66]

Poland

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Poland begins in the 1870s when Polish writer Walerian Jablonowski[79] wrote several articles covering its early history in Persia.[4][80] There was a polish language translation of Paris Talks published in 1915.[81] After becoming a Baháʼí in 1925[82] Poland's Lidia Zamenhof returned to Poland in 1938 as its first well known Baháʼí. During the period of the Warsaw Pact Poland adopted the Soviet policy of oppression of religion, so the Baháʼís, strictly adhering to their principle of obedience to legal government, abandoned its administration and properties.[83] An analysis of publications before and during this period finds coverage by Soviet-based sources basically hostile to the religion while native Polish coverage was neutral or positive.[80] By 1963 only Warsaw was recognized as having a community.[84] Following the fall of communism in Poland because of the Revolutions of 1989, the Baháʼís in Poland began to initiate contact with each other and have meetings – the first of these arose in Kraków and Warsaw.[81] In March 1991 the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly was re-elected in Warsaw. Poland's National Spiritual Assembly was elected in 1992.[85] There were about three hundred Baháʼís in Poland in 2006 and there have been several articles in polish publications in 2008 covering the persecution of Baháʼís in Iran and Egypt.[86]

Slovakia

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Slovakia begins after 1916 with a mention by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, then head of the religion, that Baháʼís should take the religion to the regions of Europe including Slovakia, then part of the Austria-Hungarian Empire.[87] It is not clear when the first Baháʼís entered Slovakia but there were Baháʼís in Czechoslovakia by 1963.[88] As the period of communism was ending, there is comment of activity in Slovakia starting around 1989.[89] Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991, Baháʼí communities and their administrative bodies started to develop across the nations of the former Soviet Union including Czechoslovakia.[36] In 1991 the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly of Bratislava was formed.[90] Separate national assemblies for Czechia and Slovakia were formed in 1998.[36] While registration with the national government of Slovakia is not required it is required for many religious activities as well as owning property.[91] In 2007 representatives of the Baháʼí Faith submitted 28,000 signatures of interested citizens to the government of Slovakia thus officially registering as a religious community[92] which then numbered about 1,065 individuals in 2011.[93]

Switzerland

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2016) |

The Baháʼí Faith in Switzerland has a history that goes back more than a hundred years. The first settlement of a resident Baháʼí in Switzerland occurred in 1903, when Edith MacKaye, a French-American, moved from Paris to Sion in the Rhone Valley, marrying Dr Joseph de Bons, a local dentist, who embraced this new religion. Abdu'l-Bahá visited Switzerland in 1911. At present, there are about 1,100 Baháʼís residing in Switzerland. This number has not increased in the past four decades. Currently, there are Baháʼí communities established in Aarau, Ayer, Basel, Bern, Biel, Carouge, Cologny, Delémont, Fribourg, Geneva, Grand-Lancy, Heiden, Lausanne, Le Lignon, Locarno, Lugano, Luzern, Meilen, Neuchatel Nyon, Olten, Pully, Reinach, Romanshorn, Schaffhausen, St-Gall, Thun, Zug and Zurich.

Eastern Europe

editAzerbaijan

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Azerbaijan crosses a complex history of regional changes. Before 1850 followers of the predecessor religion Bábism were established in Nakhichevan.[94] By the early 20th century the Baháʼí community, now centered in Baku, numbered perhaps 2,000 individuals and several Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assemblies[2] had facilitated the favorable attention of local and regional,[94] and international[95] leaders of thought as well as long standing leading figures in the religion.[40] However under Soviet rule the Baháʼí community was almost ended[96] though it was immediately reactivated as perestroyka loosened controls on religions[2] and re-elected its own National Spiritual Assembly in 1992.[85] The modern Baháʼí population of Azerbaijan, centered in Baku, may have regained its peak from the oppression of the Soviet period of about 2,000 people, today with more than 80% converts[97] although the community in Nakhichevan, where it all began, is still seriously harassed and oppressed.[98]

Armenia

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Armenia begins with some involvements in the banishments and execution of the Báb,[99] the Founder of the Bábí Faith, viewed by Baháʼís as a precursor religion. The same year of the execution of the Báb the religion was introduced into Armenia.[94] During the period of Soviet policy of religious oppression, the Baháʼís in Armenia lost contact with the Baháʼís elsewhere.[83] However, in 1963 communities were identified[100] in Yerevan and Artez.[85] Following Perestroika the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assemblies of Armenia form in 1991[101] and Armenian Baháʼís elected their first National Spiritual Assembly in 1995.[85] As of 2004 the Baháʼís claim about 200 members in Armenia[102] but as of 2001 Operation World estimated about 1,400.[103]

Georgia

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Georgia begins with its arrival in the region in 1850 through its association with the precursor religion the Bábí faith during the lifetime of Baháʼu'lláh.[94] During the period of Soviet policy of religious oppression, the Baháʼís in the Soviet Republics lost contact with the Baháʼís elsewhere.[83] However, in 1963 an individual was identified[100] in Tbilisi.[104] Following Perestroika the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly of Georgia formed in 1991[101] and Georgian Baháʼís elected their first National Spiritual Assembly in 1995.[85] The religion is noted as growing in Georgia.[94]

Russia

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Russia begins with connections during the Russian rule in Azerbaijan in the Russian Empire in figure of a woman who would play a central role in the religion of the Báb, viewed by Bahá´ís as the direct predecessor of the Baháʼí Faith - she would be later named Tahirih.[105] Soon after, Russian diplomats to Persia[43] would observe, react to, and sends updates about, the Bábí religion which was succeeded by their encounters with Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith.[4] While the religion spread across the Russian Empire[3][4] and attracted the attention of scholars and artists,[43] the Baháʼí community in Ashgabat built the first Baháʼí House of Worship, elected one of the first Baháʼí local administrative institutions and was a center of scholarship. During the period of the Soviet Union, Russia adopted the Soviet policy of oppression of religion, so the Baháʼís, strictly adhering to their principle of obedience to legal government, abandoned its administration and properties[41] but in addition Baháʼís across the Soviet Union were sent to prisons and camps or abroad.[42] Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union Baháʼís in several cities were able to gather and organize as Perestroyka approached from Moscow through many Soviet republics.[2] The National Assembly of the Russian Federations was ultimately formed in 1995.[85] The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated the Baháʼís in Russia at about 18,990 in 2005.[66]

Ukraine

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Ukraine began during the policy of oppression of religion in the former Soviet Union. Before that time, Ukraine, as part of Russia, would have had indirect contact with the Baháʼí Faith as far back as 1847.[4] Following the Ukrainian diasporas, succeeding generations of ethnic Ukrainians became Baháʼís and some have interacted with Ukraine previous to development of the religion in the country. There are currently around 1,000 Baháʼís in Ukraine in 13 communities.[3][106]

Northern Europe

editDenmark

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Denmark began in 1925 but it was more than 20 years before the Baháʼí community in Denmark began to grow after the arrival of American Baháʼí pioneers in 1946. Following that period of growth, the community established its Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly in 1962. With Iranian Baháʼí refugees and convert Danes the modern community was about 330 Baháʼís as of 2011.3[107]

Finland

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Finland began with contact between traveling Scandinavians with early Persian believers of the Baháʼí Faith in the mid-to-late 19th century[108] while Finland was politically part of the Russian Empire. In the early 20th century ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, then head of the religion, requested Baháʼís from the United States and Canada consider Scandinavian countries and Russia among the places Baháʼís shouldpioneer to.[109] Later, after Finland gained independence from Russia, Baháʼís began to visit the Scandinavian area in the 1920s.[110] Following a period of more Baháʼí pioneers coming to the country, Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assemblies spread across Finland while the national community eventually formed a Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly in 1962.[111] Some estimates in 2003 of the Baháʼís in Finland number about 500 Baháʼís[112][113] though they include a winner of human rights award[114] and a television personality.[115]

Iceland

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Iceland began when Amelia Collins first visiting Iceland in 1924,[116] and met with Holmfridur Arnadottir who became the first Icelandic Baháʼí.[117] The Baháʼí Faith was recognized as a religious community in 1966 and the first Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly was elected in 1972.[118] Currently around 400 Baháʼís in the country and 13 Local Spiritual Assemblies. The number of assemblies is the highest percentage, by population, in all of Europe.[118]

Norway

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Norway began with contact between traveling Scandinavians with early Persian believers of the Baháʼí Faith in the mid-to-late 19th century.[108] Baháʼís first visited Scandinavia in the 1920s following ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's, then head of the religion, request outlining Norway among the countries Baháʼís should pioneer to[109] and the first Baháʼí to settle in Norway was Johanna Schubartt.[110] Following a period of more Baháʼí pioneers coming to the country, Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assemblies spread across Norway while the national community eventually formed a Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly in 1962.[111] There are currently around 1,000 Baháʼís in the country.[119]

Sweden

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Sweden began after coverage in the 19th century[108] followed by several Swedish-Americans who had metʻAbdu'l-Bahá in the United States around 1912 and pioneered or visited the country starting in 1920.[120] By 1932 translations of Baháʼí literature had been accomplished and around 1947 the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly had been elected in Stockholm.[121] In 1962 the first National Spiritual Assembly of Sweden was elected.[122] The Baháʼís claim about 1,000 members and 25 local assemblies in Sweden.[123]

Southern Europe

editAndorra

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Andorra begins with the first mention of Andorra in Baháʼí literature when ʻAbdu'l-Bahá listed it as a place to take the religion to in 1916.[109] The first Baháʼí to pioneer to Andorra was William Danjon Dieudonne in 1953.[124] By 1979 a Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly in Andorra-la-Vella is known.[125] In 2005 according to the Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) there were about 80 Baháʼís in Andorra.[126] In 2010 Wolfram Alpha estimated about 120 Baháʼís.[127]

Italy

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Italy begins before 1899 – the earliest known date for Baháʼís in Italy.[128] ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, head of the religion from 1892 to 1921, wrote two letters to Italian Baháʼís and mentioned Italy a few times addressing issues of war and peace as well.[32] Though several people joined the religion before World War II by the end there may have been just one Baháʼí in the country.[129] Soon a wave of pioneers was coordinated[107] with the first Baháʼís to arrive were Angeline and Ugo Giachery.[40][130] By Ridván 1948 the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly of Rome was elected.[131] There were six communities across Italy and Switzerland when a regional national assembly was formed in 1953.[132] The Italian Baháʼís elected their own National Spiritual Assembly in 1962.[85] A survey of the community in 1963 showed 14 assemblies and 18 smaller communities.[133] Major conferences held in Italy include the Palermo Conference of 1968 to commemorate from the movement of Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the religion, from Gallipoli to the prison in Acre[134] and the 2009 regional conference for southern Europe in Padua about the progress of the religion.[135] The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying mostly on the World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 4,900 Baháʼís in Italy in 2005.[66]

Portugal

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Portugal comes after the first mention of Portugal in Baháʼí literature when ʻAbdu'l-Bahá mentioning it as a place to take the religion to in 1916.[109] The first Baháʼí visitor to Portugal was in 1926.[136] Its first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly was elected in Lisbon in 1946.[136] In 1962 the Portuguese Baháʼís elected their first National Spiritual Assembly.[137] In 1963 there were nine assemblies.[138] According to recent counts close to some 2,000 members of the Baháʼí Faith in 2005 according to the Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia).[66]

Spain

editThe history of the Baháʼí Faith in Spain begins with coverage of events in the history of the Bábí religion in the 1850s.[139] The first mention of Spain in Baháʼí literature was ʻAbdu'l-Bahá mentioning it as a place to take the religion to in 1916.[109] The first Baháʼí to visit Spain was in 1930[140] and the first pioneer to stay was Virginia Orbison in January 1947.[141] Following some conversions to the religion the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly of Madrid was elected in 1948.[142] The first National Spiritual Assembly was elected in 1962.[85] Following the election the breadth of initiatives of the community increased privately until 1968 when the national assembly was able to register as a Non-Catholic Religious Association in the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Information and Tourism allowing public religious events and publication and importation of religious materials.[143] Following this the diversity of initiatives of the community significantly expanded. Baháʼís began operating a permanent Baháʼí school[144] and in 1970 the first Spanish Roma joined the religion.[145] Fifty years after the first local assembly there were 100 assemblies.[146] The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 12,800 Baháʼís in 2005.[66] In 2008 the Universal House of Justice picked the Spanish community to host a regional conference for the Iberian peninsula and beyond.[147]

Vatican City

editVatican City is one of the two countries believed to have no Baháʼís at least as of 2008. The other is North Korea.[148]

Southeastern Europe

editAlbania

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Albania was introduced in the 1930s by Refo Çapari, an Albanian politician.[149] In 1967 along with the other religions the Baháʼí Faith was banned, however, after the collapse of the Communist regime in 1992 the Baháʼí community was re-established. Over the recent years several Baháʼí education centres have also been founded.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Bosnia and Herzegovina begins with mention by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá,[32] then head of the religion, of Austria-Hungary which Bosnia and Herzegovina were part of at the time. Between the World Wars when Bosnia and Herzegovina were part of Yugoslavia, several members of Yugoslavian royalty had contact with prominent members of the religion.[150] During the period of Communism in Yugoslavia, the first member of the Baháʼí Faith was in 1963 and the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly was formed in 1990.[151] With the Yugoslavian civil war and separation into Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Baháʼís had not elected a Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly[101] but do have a small population in a few regions in the country.[152]

Moldova

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Moldova began during the policy of oppression of religion in the former Soviet Union. Before that time, Moldova, as part of the Russian Empire, would have had indirect contact with the Baháʼí Faith as far back as 1847.[3][4] In 1974 the first Baháʼí arrived in Moldova.[153] and following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991, communities of Baháʼís, and respective National Spiritual Assemblies, developed across the nations of the former Soviet Union.[36] In 1996 Moldova elected its own National Spiritual Assembly.[85] There were about 400 Baháʼís in Moldova in 2004.[154]

Turkey

editThe Baháʼí Faith in Turkey has a history that goes back to the roots of the religion from the first Bábi, an immediate predecessor religion associated with the Baháʼí Faith, to reach Istanbul, Mullá 'Alíy-i-Bastámí,[46] through the initial banishment of Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the religion, from Persia into then Ottoman cities of Baghdad, and then further banishments to Istanbul, Edirne, and ultimately Acre during which significant portions of the writings of Baháʼu'lláh took place. Succeeding that period we have the history of the spread of the community through a history of trials adjudicating the legal standing of the religion in the country as progressively wider scales of organization of the religion are attempted. In the new millennium many of the obstacles to the religion remain in place – Baháʼís cannot register with the government officially[155] but there are probably 10[156] to 20[157] thousand Baháʼís, and around a hundred Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assemblies in Turkey.[46]

Western Europe

editFrance

editThe Baháʼí Faith in France started after French citizens observed and studied the religion in its native Persia in the 19th century.[158] Following the introduction of followers of the religion shortly before 1900 the community grew and was assisted by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's trip to France in 1911 and 1912.[22] After growth and tribulation the community established its National Assembly in 1958. The community has been reviewed a number of times by researchers.[159][160][161] According to the 2005 Association of Religion Data Archives data there are close to some 4,400 Baháʼís in France[66] and the French government is among those who have been alarmed at the treatment of Baháʼís in modern Iran.[67]

The Netherlands

editThe first mentions of the Baháʼí Faith in the Netherlands were in Dutch newspapers which in 1852 covered some of the events relating to the Bábí movement which the Baháʼí Faith regards as a precursor religion.[8] Circa 1904 Algemeen Handelsblad, an Amsterdam newspaper, sent a correspondent to investigate the Baháʼís in Persia.[162] The first Baháʼís to settle in the Netherlands were a couple of families – the Tijssens and Greevens, both of whom left Germany for the Netherlands in 1937.[163] Following World War II the Baháʼís established a committee to oversee introducing the religion across Europe and so the permanent growth of the community in the Netherlands begins with Baháʼí pioneers arriving in 1946.[163] Following their arrival and conversions of some citizens, the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly of Amsterdam was elected in 1948.[164] In 1957, with 110 Baháʼís and nine spiritual assemblies, the Baháʼí community in the Netherlands first elected its own National Spiritual Assembly.[163] In 2005 the Netherlands had 34 local spiritual assemblies.[164] In 1997 there were about 1500 Baháʼís in The Netherlands.[165]

United Kingdom

editThe Baháʼí Faith in the United Kingdom started with the earliest mentions of the predecessor of the Baháʼí Faith, the Báb, in British newspapers. Some of the first British people who became members of the Baháʼí Faith include George Townshend and John Esslemont. Through the 1930s, the number of Baháʼí in the United Kingdom grew, leading to a pioneer movement beginning after the Second World War with sixty percent of the British Baháʼí community eventually relocating. In 2004 there were about 5,000 Baháʼís in the UK.[166]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Baháʼí Information Office (United Kingdom) (1989). "First Public Mentions of the Baháʼí Faith". Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Geschichte (100 Jahre)". Official website of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Germany. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Germany. Archived from the original on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Local Spiritual Assembly of Kyiv (August 2007). "Statement on the history of the Baháʼí Faith in Soviet Union". Official Website of the Baháʼís of Kyiv. Local Spiritual Assembly of Kyiv. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Momen, Moojan. "Russia". Draft for "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith". Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- ^ Momen, Moojan (2004), "Conspiracies and Forgeries: the attack upon the Baha'i community in Iran" (PDF), Persian Heritage, 9 (35): 27–29

- ^ Balyuzi, H.M. (1973), The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, Oxford, UK: George Ronald, p. 131, ISBN 0-85398-048-9

- ^ Balyuzi, H.M. (2000), Baháʼu'lláh, King of Glory, Oxford, UK: George Ronald, pp. 77–78, 99–100, ISBN 0-85398-328-3

- ^ a b de Vries 2002, pp. 18–20

- ^ Warburg, Margit (2006). Hanegraaff, W.J.; Kumar, P.P. (eds.). Citizens of the World; A History and Sociology of the Baha'is from a Globalization Perspective. Numen Book Series Studies in the History of Religions. Vol. 106. Koninklijke Brill NV. pp. 34–35, 147. ISBN 978-90-04-14373-9.

- ^ Baháʼí International Community (30 November 1992). "Statement in rebuttal of Accusations made against the Baha'i Faith by the Permanent Mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations General Assembly, 37th session, November 1982" (PDF). Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Cole, Juan. "Baha'u'llah's Tablets to the Rulers". Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ Universal House of Justice (6 November 1997). "Responses of Napoleon III and Queen Victoria to the Tablets of Baha'u'llah". Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi (1996). Promised Day is Come. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. g. 65. ISBN 0-87743-244-9.

- ^ Momen, Moojan (1981), The Babi and Baha'i Religions, 1844-1944: Some Contemporary Western Accounts, Oxford, England: George Ronald, ISBN 0-85398-102-7

- ^ See:

- 'Bab et les Babis', Journal asiatique, Publisher Société asiatique, April–May 1866, pp. 329–384,

- 'Bab et les Babis', Journal asiatique, Publisher Société asiatique, June 1866, pp. 457–522.

- 'Bab et les Babis', Journal asiatique, Publisher Société asiatique, August–September 1866, pp. 196–252.

- 'Bab et les Babis', Journal asiatique, Publisher Société asiatique, October–November 1866, pp. 357–400.

- ^ de Vries 2002, pp. 24

- ^ U.K. Baháʼí Heritage Site. "The Baháʼí Faith in the United Kingdom -A Brief History". Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ de Vries 2002, pp. 19, 43–46

- ^ a b Early Western Accounts of the Babi and Baháʼí Faiths by Moojan Momen

- ^ Bibliographie des ouvrages de langue française mentionnant les religions babie ou bahaʼie (1844–1944) compiled by Thomas Linard, published in Occasional Papers in Shaykhi, Babi and Baháʼí Studies, 3, 1997–06

- ^ Bausani, Alessandro and Dennis MacEoin (1989). "Abd-al-Bahā". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ a b c d Balyuzi 2001, pp. 159–397, 373–379

- ^ various (20 August 1911). Windust, Albert R; Buikema, Gertrude (eds.). "various". Star of the West. 02 (9). Chicago, USA: Baháʼí News Service: all. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá; Wellesley Tudor Pole (1911). "The Bahai Movement". In Spiller, G. (ed.). Papers on Inter-racial Problems Communicated to the First Universal Races Congress. London: in London, P.S. King & Son and Boston, The World's Peace Foundation. pp. 154–157. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Hippolyte Dreyfus, apôtre d'ʻAbdu'l-Bahá; Premier Baháʼí français". Qui est ʻAbdu'l-Bahá ?. Assemblée Spirituelle Nationale des Baháʼís de France. 9 July 2000. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ Thompson, Juliet; Marzieh Gail (1983). The diary of Juliet Thompson. Kalimat Press. pp. 147–223, Chapter With ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Thonon, Vevey, and Geneva. ISBN 978-0-933770-27-0.

- ^ Honnold, Annamarie (2010). Vignettes from the Life of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. UK: George Ronald. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-85398-129-9. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1 October 2006). "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in London". National Spiritual Assembly of Britain. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- ^ Lady Blomfield (1 October 2006). "The Chosen Highway". Baha'i Publishing Trust Wilmette, Illinois. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ Balyuzi 2001, p. 343

- ^ ʻAbbas, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (April 1919). Tablets, Instructions and Words of Explanation. Translated by Mirza Ahmad Sohrab.

- ^ a b c ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916-17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 43. ISBN 0-87743-233-3.

- ^ The Baháʼí World: A Biennial International Record, Volume II, 1926–1928 (New York City: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1928), 182–85.

- ^ a b Effendi, Shoghi (1974). Baháʼí Administration. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-166-3.

- ^ The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953-1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, pages 22 and 46.

- ^ a b c d Hassall, Graham; Fazel, Seena. "100 Years of the Baháʼí Faith in Europe". Baháʼí Studies Review. Vol. 1998, no. 8. pp. 35–44.

- ^ "May Ellis Maxwell". Biographies. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ^ German Baháʼí News Service (25 April 2007). "German town re-erects monument". Baháʼí World News Service.

- ^ a b c d e Kolarz, Walter (1962). Religion in the Soviet Union. Armenian Research Center collection. St. Martin's Press. pp. 470–473. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d Universal House of Justice (1986). "In Memoriam". The Baháʼí World. XVIII. Baháʼí World Centre: 797–800. ISBN 0-85398-234-1.

- ^ a b Effendi, Shoghi (11 March 1936). The World Order of Baháʼu'lláh. Haifa, Palestine: US Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1991 first pocket-size edition. pp. 64–67.

- ^ a b Momen, Moojan (1994). "Turkmenistan". draft of "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baha'i Faith". Baháʼí Library Online. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ a b c "Notes on the Bábí and Baháʼí Religions in Russia and its Territories" Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, by Graham Hassall, Journal of Baháʼí Studies, 5.3 (September–December 1993)

- ^ Warburg, Margit (2004). Peter Smith (ed.). Baháʼís in the West. Kalimat Press. pp. 228–63. ISBN 1-890688-11-8.

- ^ a b Rabbani, R., ed. (1992). The Ministry of the Custodians 1957-1963. Baháʼí World Centre. pp. 85, 124, 148–151, 306–9, 403, 413. ISBN 0-85398-350-X.

- ^ a b c Walbridge, John (March 2002). "Chapter Four – The Baha'i Faith in Turkey". Occasional Papers in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies. 06 (1).

- ^ Marks, Geoffry W.; Universal House of Justice (1996). Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1963-1986: the Third Epoch of the Formative Age. Wilmette, Illinois: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 37–8. ISBN 0-87743-239-2.

- ^ "Historie". Official Website of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Germany. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Germany. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ Francis, N. Richard. "Excerpts from the lives of early and contemporary believers on teaching the Baháʼí Faith: Enoch Olinga, Hand of the Cause of God, Father of Victories". Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). "conferences and congresses, international". A concise encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 109–110. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ High-ranking member of the Baha'i Faith passes away 26 November 2003

- ^ Dunlop, John B. (1998). "Russia's 1997 Law Renews Religious Persecution" (PDF). Demokratizatsiya. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ^ a b Momen, Moojan. "History of the Baha'i Faith in Iran". draft "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baha'i Faith". Bahai-library.com. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ^ Kingdon, Geeta Gandhi (1997). "Education of women and socio-economic development". Baháʼí Studies Review. 7 (1).

- ^ Momen, Moojan; Smith, Peter (1989). "The Baha'i Faith 1957–1988: A Survey of Contemporary Developments". Religion. 19: 63–91. doi:10.1016/0048-721X(89)90077-8.

- ^ "AGENDA 21 - Sustainable Development: Introduction to UK project". 21 August 2003. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ International Community, Baháʼí (5 November 2000). "500,000 people visit Baha'i exhibit at the Hanover Expo 2000". Baháʼí World News Service.

- ^ International Community, Baháʼí (4 June 2002). "Faith groups, including Baha'is of Germany, meet on environment and climate concerns". Baháʼí World News Service.

- ^ "Baháʼí-projekt". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Sweden. Archived from the original on 4 February 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ International Community, Baháʼí (31 May 2005). "Senior government minister praises Baha'i contributions". Baháʼí World News Service.

- ^ Micksch, Jürgen (2009). "Trialog International - Die jährliche Konferenz". Herbert Quandt Stiftung. Archived from the original on 23 May 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ^ "Sweden 2005". Nordic Baha'i Youth Conferences. Vikings, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ "Sweden 2009". Nordic Baha'i Youth Conferences. Vikings, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ "Media (Pics & Vids)". Summer School Committee. 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ Baháʼí International Community (8 February 2009). "The Frankfurt Regional Conference". Baháʼí World News Service.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Most Baháʼí Nations (2005)". QuickLists > Compare Nations > Religions >. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ a b UN Commission expresses concern over human rights violations in Iran

- ^ "We are ashamed! Century and a half of silence towards oppression against Bahais is enough". Iranian.com. 4 February 2009. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009.

- ^ "Stand up for Iran's Bahaʼis - Voices from the arts call for the imprisoned Baha'i leaders in Iran to receive a fair trial". The Times. London. 26 February 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "Trial of members of the Iranian Baháʼí community" (Press release). Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 16 February 2009. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ Official English news page of the Baháʼí Community of Hungary.

- ^ "Baháʼís of Hungary to the Baháʼís and Government of Iran". Hans Peterson. 10 May 2009. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ Hungarian personalities speak out for human rights in Iran.

- ^ Mooman, Moojan (2004). Peter Smith (ed.). Baháʼís in the West. Kalimat Press. pp. 63–109. ISBN 1-890688-11-8.

- ^ "Verschiedene Gemeinschaften / neuere religiöse Bewegungen". Religionen in Deutschland: Mitgliederzahlen (Membership of religions in Germany). REMID – the "Religious Studies Media and Information Service" in Germany. August 2007. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ^ Lederer, György (2004). "ʻAbdu'l-Baha in Budapest". In Smith, Peter (ed.). Baháʼís in the West. Studies in the Bábí and Baháʼí religions. Vol. 14. Kalimat Press. pp. 109–126. ISBN 978-1-890688-11-0.

- ^ "A Draft Summary of the History and International Character of the Hungarian Baháʼí Community". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of Hungary. 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ Mallows, Lucy (5 December 2002). "Baháʼí community celebrates new center". Budapest Sun (Hungary). Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ "History in Poland". Official Webpage of the Baháʼís of Poland. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Poland. 2008. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ^ a b Jasion, Jan T. (1999). "The Polish Response to Soviet Anti-Baháʼí Polemics". Associate. Vol. Winter 1999, no. 29. Association for Baháʼí Studies (English-Speaking Europe). Archived from the original on 15 February 2012.

- ^ a b National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of South Africa (1997). "Baháʼís in South Africa – Progress of the Baháʼí Faith in South Africa since 1911". Official website. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of South Africa. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). "Zamenhof, Lidia". A concise encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. p. 368. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ a b c Effendi, Shoghi (11 March 1936). The World Order of Baháʼu'lláh. Haifa, Israel: US Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1991 first pocket-size edition. pp. 64–67.

- ^ The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, page 109

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hassall, Graham. "Notes on Research on National Spiritual Assemblies". Research notes. Asia Pacific Baháʼí Studies. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "Press about the Baháʼí Faith". Official Webpage of the Baháʼís of Poland. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Poland. 2008. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916–17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 40/42. ISBN 0-87743-233-3.

- ^ Hands of the Cause. "The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963". p. 78.

- ^ "Who are we?". Official website of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Slovakia. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Slovakia. 2008. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ Ahmadi (2003). "Major events of the Century of Light". webpage for an online course on the book "Century of Light". Association for Baháʼí Studies in Southern Africa. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ U.S. State Department (14 September 2007). "Slovak Republic – International Religious Freedom Report 2007". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ Baháʼí International Community (13 May 2007). "Slovak government recognizes Baha'i Faith". Baháʼí World News Service.

- ^ "Freedom in the World – Slovakia (2008)". Freedom House. 2008. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Balci, Bayram; Jafarov, Azer (21 February 2007), "The Bahaʼis of the Caucasus: From Russian Tolerance to Soviet Repression {2/3}", Caucaz.com, archived from the original on 24 May 2011

- ^ Stendardo, Luigi (30 January 1985). Leo Tolstoy and the Baháʼí Faith. London, UK: George Ronald Publisher Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85398-215-9. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ Hassall, Graham (1993). "Notes on the Babi and Baha'i Religions in Russia and its territories". The Journal of Baháʼí Studies. 05 (3). Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ^ Balci, Bayram; Jafarov, Azer (20 March 2007), "The Bahaʼis of the Caucasus: From Russian Tolerance to Soviet Repression {3/3}", Caucaz.com

- ^ U.S. State Department (15 September 2006). "International Religious Freedom Report 2006– Azerbaijan". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- ^ Quinn, Sholeh A. (2009). "Aqasi, Haji Mirza (ʻAbbas Iravani)". Baháʼí Encyclopedia Project. Evanston, Illinois: National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United States.

- ^ a b Monakhova, Elena (2000). "From Islam to Feminism via Baha'i Faith". Women Plus…. Vol. 2000, no. 3.

- ^ a b c Ahmadi, Dr. (2003). "Major events of the Century of Light". homepage for an online course on the book "Century of Light". Association for Baháʼí Studies in Southern Africa. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ U.S. State Department (2005). "Armenia International Religious Freedom Report 2004". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ "Republic of Armenia, Hayastan". Operation World. Paternoster Lifestyle. 2001. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- ^ Hands of the Cause. "The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963". p. 84.

- ^ "Baha'i Faith History in Azerbaijan". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. State Department. 15 September 2004. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ a b Warburg, Margit (2004). Peter Smith (ed.). Baháʼís in the West. Kalimat Press. pp. 228–63. ISBN 1-890688-11-8.

- ^ a b c National Spiritual Assembly of Norway (2007–2008). "Skandinavisk Baháʼí historie". Official website of the Baháʼís of Norway. National Spiritual Assembly of Norway. Archived from the original on 9 September 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ a b c d e ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916–17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 31–32. ISBN 0-87743-233-3.

- ^ a b National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Norway (25 March 2008). "Johanna Schubarth". Official website of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Norway. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Norway. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ a b The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, pages 22 and 46.

- ^ "Other Churches and Religions in Finland". Laura Maria Raitis. December 2004. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ "Religion in Finland". 24-7Prayer.com. 2003. Archived from the original on 20 March 2005. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ "In Finland, an emphasis on diversity leads to human rights award". OneCountry. Vol. 15, no. 3. October–December 2003.

- ^ "Finnish TV talk show host finds success in unconventional approach". Baháʼí World News Service. 9 December 2007.

- ^ Francis, Richard. "Amelia Collins the fulfilled Hope of ʻAbdu'l-Baha". Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ^ Universal House of Justice (1976). Messages from the Universal House of Justice 1968–73. Wilmette, Illinois: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 205.

- ^ a b Hassall, Graham; Fazel, Seena (1998). "100 Years of the Baháʼí Faith in Europe". Baháʼí Studies Review (8): 35–44.

- ^ Statistics Norway (2008). "Members of religious and life stance communities outside the Church of Norway, by religion/life stance". Church of Norway and other religious and life stance communities. Statistics Norway. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Collins, William (1982). Moojan Momen (ed.). Studies in Babi and Baha'i History, volumes 1, chapter: Kenosha, 1893–1912: History of an Early Baháʼí Community in the United States. Kalimat Press. p. 248. ISBN 1-890688-45-2.

- ^ "August og Anna Ruud". National Spiritual Council of the Baha'is in Norway. Archived from the original on 9 September 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ Hands of the Cause. "The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963". p. 116.

- ^ "English Summary". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Sweden. Archived from the original on 9 September 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ "Mountainous country marks anniversary". Baháʼí International News Service. Andorra la Vella, Andorra: Baháʼí International Community. 18 November 2004. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ "Victory Messages; The Baha'i world resounds with the glorious news of Five Year Plan victories (section mentioning Andorra)". Baháʼí News. No. 581. August 1979. p. 11. ISSN 0043-8804.

- ^ "Andorra". International > Regions > Southern Europe. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ "Andorra: population, capital, cities, GDP, map, flag, currency, languages, ..". Wolfram Alpha. Vol. Online. Wolfram – Alpha (curated data(. 13 March 2010. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ "Report form Italy". Baháʼí News. No. 43. August 1930. p. 8. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "News From Other Lands; Italy". Baháʼí News. No. 10. September 1946. pp. 18–20. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "Four More Pioneers Leave for Europe". Baháʼí News. No. 192. February 1947. p. 1. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "Europeau Enrollments Increase". Baháʼí News. No. 205. March 1948. p. 9. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "First Annual Convention Baháʼís of Italy and Switzerland". Baháʼí News. No. 266. April 1953. p. 2. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ Hands of the Cause. "The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963". pp. 93–94, 111, 112.

- ^ "From Ciallipoli to the Most Great Prison; Message from the Universal House of Justice to Palermo". Baháʼí News. No. 451. October 1968. pp. 1–2. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "The Padua Regional Conference". Baháʼí World News Service. Padua, Italy: Baháʼí International Community. 7–8 February 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ^ a b Moreira, Rute (13 January 2001). "Comunidade Baháʼí em Portugal". Correio da Manhã. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2004). Baháʼís in the West. Kalimat Press. pp. 22, 36–38. ISBN 978-1-890688-11-0.

- ^ Hands of the Cause. "The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963". p. 109.

- ^ Egea, Amin (10–13 July 2003). "Chronicles of a Birth: Early References to the Bábí and Baháʼí Religions in Spain (1850–1853)". Lights of Irfan. Vol. 05. Center for Baháʼí Studies: Acuto, Italy: Irfan Colloquia. pp. 59–76. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ Mitchell, Glenford (5 October 1996). "Whatever happened to the Double Crusade?". Informal Talks by Notable Figures. Foundation Hall, US Baháʼí House of Worship, Wilmette, Illinois: Baháʼí Academics Resource Library. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ "Seventh Pioneer Flies to Lisbon". Baháʼí News. No. 191. January 1947. p. 1.

- ^ "Virginia Orbison – A Baha'i pioneer recalls 40 years of service to Faith". Baháʼí News. No. 586. January 1980. pp. 1–5.

- ^ "Granted NSA of Spain". Baháʼí News. No. 446. May 1968. p. 11.

- ^ "News Briefs". Baháʼí News. No. 449. March 1972. p. 7.

- ^ "Spain". Baháʼí News. No. 469. November 1970. p. 14.

- ^ "Carta abierta a los pueblos de España". Official website of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Spain. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Spain. 1997. Archived from the original on 14 December 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ^ Baháʼí International Community (11 November 2008). "The Madrid Regional Conference". Baháʼí International News Service.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge University Press. pp. 79, 95. ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2001). A dictionary of Albanian religion, mythology and folk culture. C. Hurst. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-85065-570-1. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi (1944). God Passes By. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 389, 395. ISBN 0-87743-020-9.

- ^ Hassall, Graham; Fazel, Seena. "100 Years of the Baháʼí Faith in Europe". Baháʼí Studies Review. Vol. 1998, no. 8. pp. 35–44.

- ^ Committee for International Pioneering and Travel Teaching (January 2003). "Report of the Committee for International Pioneering and Travel Teaching" (PDF). Baháʼí Journal of the Baháʼí Community of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. 19 (7).

- ^ Ahmadi, Dr. (2003). "Major events of the Century of Light". homepage for an online course on the book "Century of Light". Association for Baháʼí Studies in Southern Africa. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ Irina, member of the Local Spiritual Assembly of Chisinau (April–July 2004). "Activities in Moldova". European Baháʼí Women's Network. 02 (2). Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ U.S. State Department (19 September 2008). "International Religious Freedom Report 2008 – Turkey". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ^ "For the first time, Turkish Baha'i appointed as dean". The Muslim Network for Bahaʼi Rights. 13 December 2008. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ^ "Turkey /Religions & Peoples". LookLex Encyclopedia. LookLex Ltd. 2008. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ^ Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, by Nader Saiedi: Review by Stephen Lambden, published in The Journal of the American Oriental Society, 130:2, 2010-04

- ^ Larousse, Pierre; Augé, Claude (1898). "Babisme". Nouveau Larousse illustré: dictionnaire universel encyclopédique. p. 647. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Cannuyer, Christian (1987). "Les Baháʼís". In Longton, J. (ed.). Fils d'Abraham. S. A. Brepols I. G. P. and CIB Maredsous. ISBN 2503823475.

- ^ Gouvion, Colette; Jouvion, Philippe (1993). The Gardeners of God: an encounter with five million Baháʼís (trans. Judith Logsdon-Dubois from "Les Jardiniers de Dieu" (published by Berg International and Tacor International, 1989.). Oxford, UK: Oneworld. ISBN 1-85168-052-7.

- ^ de Vries 2002, pp. 65–69

- ^ a b c C. van den Hoonaard, Will (8 November 1993). "Netherlands". draft of A Short Encyclopedia of the Baha'i Faith. Baha'i Library Online. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^ a b Vieten, Gunter C. (2006). "The Dutch Baha'i Community". Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ^ Hoekstra & Ypenburg 2000, pp. 61

- ^ "In the United Kingdom, Baháʼís promote a dialogue on diversity". One Country. 16 (2). July–September 2004.

Sources

edit- Balyuzi, H.M. (2001). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant of Baháʼu'lláh (Paperback ed.). Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-043-8.

- de Vries, Jelle (2002). The Babi Question You Mentioned--: The Origins of the Baha'i Community of the Netherlands, 1844-1962. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-1109-3.

- Hoekstra, E.G.; Ypenburg, M.H. (2000). Wegwijs in religieus en levensbeschouwelijk Nederland. Kampen: Uitgeverij Kok. ISBN 90-435-0028-3.

Further reading

edit- Fazel, Seena (2022). "Ch. 43: Europe". In Stockman, Robert H. (ed.). The World of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. pp. 532–545. doi:10.4324/9780429027772-50. ISBN 978-1-138-36772-2. S2CID 244706754.

- Warburg, Margit (2006). Citizens of the World: A History and Sociology of the Bahaʹis from a Globalisation Perspective. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14373-9.