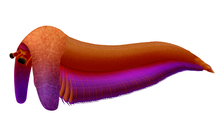

Balhuticaris is a genus of extinct bivalved (referring to the carapace) hymenocarine arthropod that lived in the Cambrian aged Burgess Shale in what is now British Columbia around 506 million years ago. This extremely multisegmented (with over 100 segments) arthropod is the largest member of the group, and it was even one of the largest animals of the Cambrian, with individuals reaching lengths of 245 mm (9 in). Fossils of this animal suggests that gigantism occurred in more groups of Arthropoda than had been previously thought.[1] It also presents the possibility that bivalved arthropods were very diverse, and filled in a lot of ecological niches.[1][2][3]

| Balhuticaris Temporal range: Cambrian,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Life restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Order: | †Hymenocarina |

| Genus: | †Balhuticaris Izquierdo-López & Caron, 2022 |

| Type species | |

| †Balhuticaris voltae Izquierdo-López & Caron, 2022

| |

The hymenocarines were an order of primitive mandibulates, the arthropod group that includes crustaceans, insects, myriapods and their relatives, that lived throughout the Cambrian period.[2] This group was extremely diverse and attained a wide variety of ecological niches and body plans.[2][3] Several dozen species are known from deposits of Cambrian, and ranged in size from smaller species like Fibulacaris nereidis reaching a length of 2 cm (0.79 in) long,[2] to larger ones like B. voltae.[1]

Discovery and Etymology

editThis arthropod was described in 2022 based on 11 specimens found in the Burgess Shale between 2014 and 2018, more specifically in the Marble canyon locality. By 2020, scientists realized that these fossils represented a new species. Because of how they were preserved the fossils were found two dimensional in several carbonaceous films. The holotype specimen and several others are nearly or fully complete with possible neural and other soft tissues having been preserved. Balhuticaris is named after Balhūt, a giant fish from Persian cosmography, as well as the Latin caris ("crab"). The specific epithet voltae is derived from the Catalan volta, meaning vault, referring to the shape of the carapace when seen from the front.[1]

Description

editBalhuticaris was the largest bivalved arthropod in the fossil record, beating the previous holders of this title Nereocaris exilis and Tuzoia. This animal's body was very long, and had extreme segmentation compared to other Cambrian arthropods, with over 100 distinct segments. In total this creature had about 110 pairs of biramous limbs, the most of any Cambrian-aged arthropod. Covering the head of this creature was a large carapace that resembles an arch or other curved structure. This structure only covers the frontmost part of this arthropod but it does extend ventrally beyond its appendages.[1]

Classification

editIn several studies performed, Balhuticaris was found to be a member of the Hymenocarina. More specifically it was found to be most closely related to the genus Odaraia and its relatives. Although they are normally regarded as pancrustaceans, this study found the Hymenocarina to occupy a more basal branch of the mandibulates.[1]

This cladogram shows the position of B. voltae in relation to other arthropods by López et al., 2022.[1]

Lifestyle

editThis hymenocarine most likely engaged in a fast-paced nektonic (free swimming) lifestyle. Its large size means that it was safe from most of the other predatory fauna of its environment. Many features of the fossils evidence a free swimming, pelagic lifestyle. Examples being the presence of a tripartite caudal rami, a feature only found in hymenocarines,[1][2] and that the carapace goes ventrally beyond the legs, which would have heavily impaired this arthropods ability to crawl on the ocean floor. Its eyes also have a similar shape seen in modern pelagic crustaceans. What this arthropod ate has been a difficult question to answer due to the lack of cephalic appendages in the fossils. Modern day arthropods of a similar size like lobsters, stomatopods, and giant isopods are mainly scavengers or predators. B. voltae however does not possess features that would suggest this, like chelate limbs and gnathobases.[1][4] Suspension and deposit feeding can also be readily ruled out due to lack of features needed for these lifestyles in B. voltae. Currently it is thought to have suctioned in prey in water currents through a ventral groove. The animal probably swam while it fed, similar to leptostracan and anostracan crustaceans.[1][5][6] It is possible that this animal swam in an upside down, or in an inverted position.[1] This is not unheard of, as many other free-swimming arthropods like anostracans,[6] pelagic trilobites like the Telephinids,[7] xiphosurans,[1] and other odaraiid hymenocarines, like Odaraia and Fibulacaris swam in inverted positions.[1][2]

Paleoecology

editThe Burgess Shale is a middle Cambrian aged Lagerstätte that lies in British Columbia in Canada.[8] This site was the first of its kind to have been discovered and provided great insights into the soft bodied fauna of the early Paleozoic.[9] Dozens of creatures have been preserved at this site including lobopodians, stem-group and total-group Arthropoda, worms, primitive chordates, echinoderms, sponges, as well as other animal groups.[10][11] This animal was one of the largest of its time, with only the giant radiodonts like Anomalocaris surpassing it in size.[1] More specifically, this animal was found in Marble Canyon. This Lagerstätte produced new taxa including other hymenocarines like Tokummia, Fibulacaris and Pakucaris, large hurdiid radiodonts like Cambroraster and Titanokorys, as well as other arthropods like the megacheiran genus Yawunik, the isoxyid genus Surusicaris, and the basal chelicerate Mollisonia plenovenatrix. Worms have also been found at this site, like the annelid Kootenayscolex. Well-preserved specimens of primitive chordate Metaspriggina are also known from there.[1][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Izquierdo-López, Alejandro (July 15, 2022). "Extreme multisegmentation in a giant bivalved arthropod from the Cambrian Burgess Shale". iScience. 25 (7): 104675. Bibcode:2022iSci...25j4675I. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2022.104675. PMC 9283658. PMID 35845166.

- ^ a b c d e f Izquierdo-López, Alejandro; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2019). "A possible case of inverted lifestyle in a new bivalved arthropod from the Burgess Shale". Royal Society Open Science. 6 (11): 191350. Bibcode:2019RSOS....691350I. doi:10.1098/rsos.191350. PMC 6894550. PMID 31827867.

- ^ a b O'Flynn, Robert; Williams, Mark; Yu, Mengxiao; Harvey, Thomas; Liu, Yu (2022-02-11). "A new euarthropod with large frontal appendages from the early Cambrian Chengjiang biota". Palaeontologia Electronica. 25: a6. doi:10.26879/1167.

- ^ Briones-Fourzán, Patricia; Lozano-Alvarez, Enrique (1 July 1991). "Aspects of the biology of the giant isopod Bathynomus giganteus A. Milne Edwards, 1879 (Flabellifera: Cirolanidae), off the Yucatan Peninsula". Journal of Crustacean Biology. 11 (3): 375–385. doi:10.2307/1548464. JSTOR 1548464.

- ^ J. K. Lowry (October 2, 1999). "Leptostraca". Crustacea, the Higher Taxa: Description, Identification, and Information Retrieval. Australian Museum. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ a b Denton Belk (2007). "Branchiopoda". In Sol Felty Light; James T. Carlton (eds.). The Light and Smith Manual: Intertidal Invertebrates from Central California to Oregon (4th ed.). University of California Press. pp. 414–417. ISBN 978-0-520-23939-5.

- ^ McCormick, T.; Fortey, R.A. (1998). "Independent testing of a paleobiological hypothesis: the optical design of two Ordovician pelagic trilobites reveals their relative paleobathymetry". Paleobiology. 24 (2): 235–253. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(1998)024[0235:ITOAPH]2.3.CO;2. JSTOR 2401241. S2CID 132509541.

- ^ Butterfield, N. J. (2003-02-01). "Exceptional Fossil Preservation and the Cambrian Explosion". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 43 (1): 166–177. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.166. ISSN 1540-7063. PMID 21680421.

- ^ Butterfield, N.J. (2006). "Hooking some stem-group" worms": fossil lophotrochozoans in the Burgess Shale". BioEssays. 28 (12): 1161–6. doi:10.1002/bies.20507. PMID 17120226. S2CID 29130876.

- ^ Conway Morris, S. (1986). "Community structure of the Middle Cambrian Phyllopod Bed (Burgess Shale)" (PDF). Palaeontology. 29 (3): 423–467. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- ^ Whittington HB, Briggs DE (1985). "The largest Cambrian animal, Anomalocaris, Burgess Shale, British Columbia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 309 (1141): 569–609. Bibcode:1985RSPTB.309..569W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1985.0096.

- ^ Aria, Cédric; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2017). "Burgess Shale fossils illustrate the origin of the mandibulate body plan". Nature. 545 (7652): 89–92. Bibcode:2017Natur.545...89A. doi:10.1038/nature22080. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 28445464. S2CID 4454526.

- ^ Izquierdo-López, Alejandro; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2019-11-13). "A possible case of inverted lifestyle in a new bivalved arthropod from the Burgess Shale". Royal Society Open Science. 6 (11): 191350. Bibcode:2019RSOS....691350I. doi:10.1098/rsos.191350. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 6894550. PMID 31827867.

- ^ Izquierdo‐López, Alejandro; Caron, Jean‐Bernard (2021). Zhang, Xi‐Guang (ed.). "A Burgess Shale mandibulate arthropod with a pygidium: a case of convergent evolution". Papers in Palaeontology. 7 (4): 1877–1894. doi:10.1002/spp2.1366. ISSN 2056-2799. S2CID 236284813.

- ^ Caron, J.-B.; Moysiuk, J. (2021). "A giant nektobenthic radiodont from the Burgess Shale and the significance of hurdiid carapace diversity". Royal Society Open Science. 8 (9): 210664. Bibcode:2021RSOS....810664C. doi:10.1098/rsos.210664. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 8424305. PMID 34527273.

- ^ Aria, Cédric; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2015-06-03). "Cephalic and Limb Anatomy of a New Isoxyid from the Burgess Shale and the Role of "Stem Bivalved Arthropods" in the Disparity of the Frontalmost Appendage". PLOS ONE. 10 (6): e0124979. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1024979A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124979. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4454494. PMID 26038846.

- ^ Aria, Cédric; Caron, Jean-Bernard; Gaines, Robert (2015). Zhang, Xi-Guang (ed.). "A large new leanchoiliid from the Burgess Shale and the influence of inapplicable states on stem arthropod phylogeny". Palaeontology. 58 (4): 629–660. doi:10.1111/pala.12161. S2CID 86443516.

- ^ Aria, Cédric; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2019). "A middle Cambrian arthropod with chelicerae and proto-book gills". Nature. 573 (7775): 586–589. Bibcode:2019Natur.573..586A. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1525-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31511691. S2CID 202550431.

- ^ Nanglu, Karma; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2018-01-22). "A New Burgess Shale Polychaete and the Origin of the Annelid Head Revisited". Current Biology. 28 (2): 319–326.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.12.019. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 29374441. S2CID 2553089.

- ^ Conway Morris, Simon; Caron, Jean-Bernard (2014-08-01). "A primitive fish from the Cambrian of North America". Nature. 512 (7515): 419–422. Bibcode:2014Natur.512..419M. doi:10.1038/nature13414. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 24919146. S2CID 2850050.