The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is a committee of the Bank of England, which meets for three and a half days, eight times a year, to decide the official interest rate in the United Kingdom (the Bank of England Base Rate).

Interest rates since the Committee's inception | |

| Formation | May 1997 |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Determining monetary policy |

Chairman | Andrew Bailey (ex officio) |

Parent organization | Bank of England |

Staff | 9 |

| Website | Monetary Policy Committee |

It is also responsible for directing other aspects of the government's monetary policy framework, such as quantitative easing and forward guidance. The Committee comprises nine members, including the Governor of the Bank of England, and is responsible primarily for keeping the Consumer Price Index (CPI) measure of inflation close to a target set by the government, currently 2% per year (as of 2019).[1] Its secondary aim – to support growth and employment – was reinforced in March 2013.

Announced on 6 May 1997, only five days after that year's General Election, and officially given operational responsibility for setting interest rates in the Bank of England Act 1998, the committee was designed to be independent of political interference and thus to add credibility to interest rate decisions. Each member has one vote, for which they are held to account: full minutes of each meeting are published alongside the committee's monetary policy decisions, and members are regularly called before the Treasury Select Committee, as well as speaking to wider audiences at events during the year.

Purpose

editThe committee is responsible for formulating the United Kingdom's monetary policy,[2] most commonly via the setting of the rate at it which it lends to banks (officially the Bank of England Base Rate or BOEBR for short).[3] As laid out in law, decisions are made with a primary aim of price stability, defined by the government's inflation target (2% per year on the Consumer Price Index as of 2016).[2] The target takes the form of a "point", rather than the "band" used by the Treasury prior to 1997.[4] The secondary aim of the committee is to support the government's economic policies, and help it meet its targets for growth and employment.[2] That secondary aim was reinforced by then Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne in his March 2013 budget, with the MPC given more discretion to more openly "trade off" above-rate inflation in the medium run to boost other economic indicators.[5] The MPC is not responsible for fiscal policy, which is handled by the Treasury itself,[4] but is briefed by the Treasury about fiscal policy developments at meetings.[3]

| Bank of England Act 1998 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| Long title | An Act to make provision about the constitution, regulation, financial arrangements and functions of the Bank of England, including provision for the transfer of supervisory functions; to amend the Banking Act 1987 in relation to the provision and disclosure of information; to make provision relating to appointments to the governing body of a designated agency under the Financial Services Act 1986; to amend Schedule 5 to that Act; to make provision relating to the registration of Government stocks and bonds; to make provision about the application of section 207 of the Companies Act 1989 to bearer securities; and for connected purposes. |

| Citation | 1998 c. 11 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 23 April 1998 |

| Commencement | 1 June 1998 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Text of the Bank of England Act 1998 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk. | |

Under the Bank of England Act 1998 (c. 11) the Bank's Governor must write an open letter of explanation to the Chancellor of the Exchequer if inflation exceeds the target by more than one percentage point in either direction, and once every three months thereafter until prices are back within the allowed range. It should also set out what plans the Bank has for rectifying the problem, and how long it is expected to remain at those levels in the meantime.[2]

In January 2009 the Chancellor announced an Asset Purchase Facility (APF), to be administered by the MPC, aimed at ensuring greater liquidity in financial markets.[6] The committee had already started to cut rates the previous autumn, but the effect of such changes can take up to two years and rates cannot go below zero. By March 2009, faced with very low levels on inflation and interest rates already at 0.5%, the MPC voted to start the process of quantitative easing (QE) – the injection of money directly into the economy – via the APF. It had the Bank buy government bonds (gilts), along with a smaller amount of high-quality debt issued by private companies.[7] Although non-gilts initially made up a non-negligible part of the APF portfolio, as of May 2015 the entirety of the APF was held as gilts.[8] On 7 August 2013, Governor Mark Carney issued the committee's first forward guidance as a third tool for controlling future inflation.[9]

Criticism of the MPC has centred on its predominant focus on inflation to the detriment of growth and employment,[2] although that criticism may have been mitigated by the March 2013 revisions to the committee's remit. There have also been complaints about the reluctance of lenders to pass on rate changes,[10] and about the extent to which the introduction and management of QE have risked politicising the committee.[11]

History

editTraditionally, the Treasury set interest rates. After reforms in 1992, officials held regular meetings and published minutes, but were not independent of government.[4] The result was a feeling that political factors were clouding what should be purely economic judgements on monetary policy.[10]

On 6 May 1997, operational responsibility to set interest rates was granted to the independent Bank of England by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown.[10] Guidelines for the creation of a new "Monetary Policy Committee" were laid out in the Bank of England Act 1998. The Act also set out the responsibilities of the MPC: it would meet monthly; its membership comprise the Governor, two Deputy Governors, two of the Bank's Executive Directors and four members appointed by the Chancellor. It should publish minutes of all meetings within six weeks (in October 1998 the committee announced plans to publish far more quickly, after only one[12]). The Act gave the government responsibility for specifying its price stability target and growth and employment objectives at least annually.[13] The original inflation target the government set for the MPC was 2.5% per year on the RPI-X measure of inflation, but in 2003 this was changed to 2% on CPI.[4] The government reserved the right to instruct the Bank on what rate to set in times of emergency.[14]

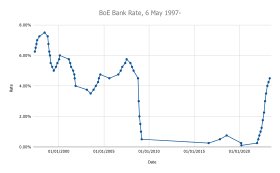

The years 1998 to 2006 witnessed an unprecedented period of price stability – during which inflation stayed within a percentage point of the target – despite earlier predictions that it could sit outside the range forty or more per cent of the time. A 2007 report produced for the Treasury Committee noted that the MPC's independence of government "has reduced the scope for short-term political considerations to enter into the determination of interest rates". The creation of the MPC, it said, brought with it "an immediate credibility gain".[4] During this time, the MPC kept interest rates relatively stable between 3.5% and 7.5%.[15]

However, the financial crisis of 2007–08 ended this period of stability, and, on 16 April 2007, the governor (at that time Mervyn King), was obliged to write the first MPC open letter to the chancellor (Gordon Brown), explaining why the inflation had deviated from the target of 2% per year by more than one percentage point (3.1%).[16] By February 2013, he had had to write 14 such letters to chancellors.[17] Between October 2008 and March 2009 the base rate was cut six times to an all-time low of 0.5% in order to avoid deflation and spur growth. In March 2009, the MPC launched a programme of quantitative easing, initially injecting £75 billion into the economy.[18] By March 2010, it had also increased the amount of money set aside for quantitative easing to £200 billion,[19] a figure later increased by a further £75 billion in the months following October 2011.[20] The MPC announced two further £50 billion rounds of quantitative easing in February[21] and July 2012,[22] bringing the total to £375 billion whilst simultaneously keeping the base rate at 0.5%.[22] In March 2013, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, called on the MPC to follow its American counterpart (the Federal Reserve Board) in committing itself to keeping interest rates low for a prolonged period of time via appropriate forward guidance,[5] which it did on 7 August.[9]

These measures eventually proved insufficient to avoid deflation. Having taken over in August 2013, Governor Mark Carney wrote his first open letter in February 2015 to explain why inflation had fallen below 1% for the first time in the MPC's history.[23] This was followed by deflation of 0.1% in April 2015, the first month of negative CPI growth since the 1960s, and triggering a second letter.[24] As of February 2015, Carney has written five such letters.[25] Following the UK's vote to leave the European Union in June 2016, the MPC cut the base rate from 0.5% to 0.25%, the first change since March 2009.[26] At the same time, it announced a further round of quantitative easing, valued at £60 billion, bringing the total to £435 billion.[26]

In December 2014, the Bank adopted the recommendations of a report prepared by Kevin Warsh aimed at improving the transparency of the committee's decision making processes.[27]

Composition

editFollowing a reshuffle in April 2014, the committee currently comprises:[3]

- The Governor of the Bank

- The three Deputy Governors for Monetary Policy, Financial Stability and Markets and Banking

- The Bank's Chief Economist

- Four external members, appointed by the Chancellor of the Exchequer for a renewable three-year term

Each member has one vote of equal weight,[3] for which they can be held publicly accountable.[4] The Governor chairs the meeting and is the last to cast a vote, acting as a casting vote in event of a tie.[28] Representatives from the Treasury may attend the meeting, but only as non-voting observers.[3]

Meetings

editThe MPC meets eight times a year,[3] including four joint meetings with the Financial Policy Committee.[27] After a half-day "pre-MPC meeting", usually the Wednesday before, meetings are held over three days, typically a Thursday, Monday and Wednesday.[3] Prior to the implementation of the reforms recommended by Kevin Warsh, meetings were generally held monthly on the Wednesday and Thursday following the first Monday of the month, although this was sometimes deviated from. In 2010, for example, the meeting was postponed from the 5/6 to the 7/10 May in order to avoid conflicting with the general election scheduled for the 6th.[29] The May 2015 meeting was similarly delayed.[30]

On the first day of the three, the Committee studies data relating to the UK economy, as well as the worldwide economy, presented by the Bank's economists and regional representatives, and topics for discussion are identified and addressed.[3] The second day consists of a main policy discussion during which MPC members explain their personal views and debate the correct course of action.[3] The Governor chooses the policy most likely to command a majority and, on the third day of the meeting, a vote is taken; each member gets one vote.[3] Those in the minority are asked to give the action they would have preferred.[3] The committee's decisions are announced at noon the day after the meeting has concluded.[28] Following a procedural change in 2015, minutes of each meeting (including the policy preference of each member) are published on the Bank's website at the same time as any decision is announced, resulting in a "Super Thursday" effect.[31] Prior to August 2015, the committee's decisions were published at noon on the final day of the meeting, but there was a two-week delay before any minutes were published.[32] Starting with the March 2015 meeting, full transcripts of meetings will also be published, albeit after an eight-year delay.[27]

Outside of meetings, members of the MPC can be called upon by Parliament to answer questions regarding their decisions, via parliamentary committee meetings, often those of the Treasury Committee. MPC members also speak to audiences throughout the country, with the same aim. Their views and expectations for inflation are also republished in the Bank's quarterly inflation report.[3]

Membership

editAs of September 2024, the current Committee comprises:[33]

- Andrew Bailey (16 March 2020 to 15 March 2028, Governor)

- Clare Lombardelli (1 July 2024 - 30 June 2029, Deputy Governor for Monetary Policy)

- Dave Ramsden (1 September 2017 – 31 August 2027, Deputy Governor for Markets and Banking)

- Sarah Breeden (1 November 2023 - 31 October 2028, Deputy Governor for Financial Stability)

- Huw Pill (6 September 2021 - 5 September 2024, Chief Economist and Executive Director for Monetary Analysis)

- Alan Taylor (2 September 2024 – 1 September 2027, external member)

- Catherine L. Mann (1 September 2021 - 31 August 2024, external member)

- Swati Dhingra (9 August 2022 - 8 August 2025, external member)

- Megan Greene (5 July 2023 - 4 July 2026, external member)

Other, former members of the committee by date of appointment are:

- Christopher Allsopp (June 2000 – May 2003)

- Dame Kate Barker (June 2001 – May 2010)

- Charles Bean (October 2000 – June 2014)

- Marian Bell (June 2002 – June 2005)

- Tim Besley (September 2006 – August 2009)

- David Blanchflower (June 2006 – May 2009)

- Ben Broadbent (July 2014 - June 2024)

- Willem Buiter (June 1997 – May 2000)

- Sir Alan Budd (December 1997 – May 1999)

- Mark Carney (July 2013 - March 2020)

- David Clementi (September 1997 – August 2002)

- Jon Cunliffe (November 2013 - October 2023)

- Spencer Dale (July 2008 – May 2014)

- Howard Davies (June – July 1997)

- Paul Fisher (March 2009 – July 2014)

- Kristin Forbes (July 2014 – June 2017)

- Sir Edward George (June 1997 – June 2003)

- Sir John Gieve (16 January 2006 – March 2009)

- Charles Goodhart (June 1997 – May 2000)

- Andy Haldane (1 June 2014 - June 2021)

- Jonathan Haskel (September 2018 - August 2024)

- Charlotte Hogg (March 2017 – 28 April 2017)

- Dame DeAnne Julius (September 1997 – May 2001)

- Mervyn King (June 1997 – June 2013)

- Richard Lambert (June 2003 – March 2006)

- Sir Andrew Large (September 2002 – January 2006)

- Rachel Lomax (July 2003 – June 2008)

- Ian McCafferty (September 2012 – August 2018)

- David Miles (June 2009 – August 2015)

- Stephen Nickell (June 2000 – May 2006)

- Adam Posen (September 2009 – August 2012)

- Michael Saunders (9 August 2016 - 9 August 2022)

- Andrew Sentance (October 2006 – May 2011)

- Nemat Shafik (August 2014 – February 2017)

- Silvana Tenreyro (5 July 2017 - 4 July 2023)

- Paul Tucker (June 2002 – 20 October 2013)

- Sir John Vickers (June 1998 – September 2000)

- Gertjan Vlieghe (September 2015 – August 2021)

- Ian Plenderleith (June 1997 – May 2002)

- Sushil Wadhwani (June 1999 – May 2002)

- David Walton (July 2005 – 21 June 2006)

- Martin Weale (August 2010 – July 2016)

The dates listed show when their current terms of appointment are due to, or did, end.

As of January 2008, Mervyn King, the Bank of England's then Governor, was the only MPC member to have taken part in every meeting since 1997.[34] As a result, after the MPC meeting in July 2013, the first after King retired, no single member had attended every meeting. As of 2016, Kate Barker is the only external member to date to have been appointed for three terms, each lasting three years.[35]

See also

edit- Federal Open Market Committee, the equivalent structure in the United States' Federal Reserve System

References

edit- ^ Bank of England, Inflation and the 2% Target, website updated 10 May 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019

- ^ a b c d e Parkin, Michael; Powell, Melanie; Matthews, Kent (2007). Economics. Addison-Wesley. pp. 642–44. ISBN 978-0-13-204122-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Monetary Policy Committee". Bank of England. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Bank of England (2007). "Treasury Committee Inquiry into the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England: Ten Years On" (PDF). The Stationery Office. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ a b Monaghan, Angela (20 March 2013). "Budget 2013: Bank of England's monetary policy remit changed". Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ "Asset Purchase Facility". Bank of England. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Quantitative Easing explained (PDF). Bank of England. ISBN 1-85730-114-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Asset Purchase Facility Results". Bank of England. 21 February 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ a b "UK interest rates held until unemployment falls". BBC News. 7 August 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ^ a b c "Monetary Policy Committee". politics.co.uk. November 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "IEA's Shadow Monetary Policy Committee votes to hold Bank Rate". Institute for Economic Affairs. December 2012. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ "Monetary Policy Committee Minutes". Bank of England. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Governance". Bank of England. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Keegan, William (2003). The prudence of Mr Gordon Brown. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-84697-1.

- ^ "Bank of England Statistical Interactive Database". Bank of England. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ "Rate hike fear as inflation jumps". BBC News. 17 April 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Wallace, Tim (15 February 2012). "High inflation forces King to explain again". City AM. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "UK interest rates lowered to 0.5%". BBC News. 5 March 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ "UK interest rates remain at record low". BBC News. 4 November 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Bank of England Adds 75 billion to Quantitative Easing Program". Central Bank News. 6 October 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Katie Allen (9 February 2012). "Bank of England injects £50bn into ailing economy". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Bank of England pumps £50bn more into economy". BBC News. 5 July 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Szu Ping Chan; Denise Roland (12 February 2015). "UK heading for deflation says Bank of England Governor Mark Carney". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "UK inflation rate turns negative". BBC News. 19 May 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Bank of England cuts growth forecast". BBC News. 4 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ a b "UK interest rates cut to 0.25%". BBC News. 4 August 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ a b c "Bank of England announces measures to bolster transparency and accountability". Monetary Policy Committee. 11 December 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Monetary Policy Committee Decisions". Bank of England. April 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Monetary Policy Committee dates for 2015 and provisional dates for 2016". Bank of England. December 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ "UK interest rates kept at record low". BBC News. 11 May 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Bank votes 8-1 to keep UK rates at record low". BBC News. 6 August 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ Giles, Chris (26 May 2015). "Bank of England shake-up aims to boost transparency". Financial Times. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ "Members of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC)". Bank of England. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ Litterick, David (31 January 2008). "Mervyn King faces a rocky road to stability". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ House of Commons Treasury Committee (2007). The Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England: re-appointment hearing for Ms Kate Barker and Mr Charlie Bean (volume 2). The Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-215-03607-0.

External links

edit- Official homepage of the MPC

- Spreadsheet showing MPC votes since 1997 Archived 29 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Monetary Policy Committee Minutes[permanent dead link]

- A comparison of the MPC and its counterparts in other countries

- Bank of England Act 1998 (full text)