This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2023) |

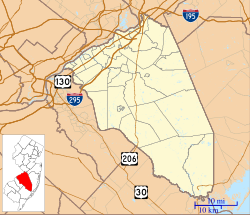

Batsto Village (or simply Batsto) is a historic unincorporated community located on CR 542 within Washington Township in Burlington County, New Jersey, United States.[3] It is located in Wharton State Forest in the south central Pine Barrens, and a part of the Pinelands National Reserve. It is listed on the New Jersey and National Register of Historic Places, and is administered by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection's Division of Parks & Forestry. The name is derived from the Swedish bastu, bathing place (also the Swedish word for Finnish sauna); the first bathers were probably the Lenni Lenape Native Americans.

Batsto Village, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

Batsto Village Mansion in 2024 | |

| Coordinates: 39°38′30″N 74°38′52″W / 39.64167°N 74.64778°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Burlington |

| Township | Washington |

| Elevation | 13 ft (4 m) |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| GNIS feature ID | 874539[1] |

Batsto Village | |

| Location | 10 mi. E of Hammonton on CR 542, Batsto, New Jersey |

|---|---|

| Area | 1,200 acres (490 ha) |

| Built | 1687 |

| Architect | Joseph Wharton |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000495[2] |

| Added to NRHP | September 10, 1971 |

History

editThe land in the vicinity of what would become Batsto was purchased from the proprietors of West Jersey in 1758 by the land speculator John Munrow.[4]: 117 John Fort ran a sawmill there for several years, attempting to buy the land with the profits from milling, but failed to meet the purchase price. It was sold to Richard Wescoat in 1764. A year later, Wescoat sold a half-interest in much of the property to Charles Read.[4]: 118

Read, a prominent lawyer, politician, and agriculturalist, had determined to become an ironmaster on a large scale. Batsto was one of several sites he fixed upon for the erection of blast furnaces. He had surveyed the tract of land, and found that it had an abundance of bog ore which could be mined from the area's streams and rivers. Wood from the area's forests could be burned for charcoal for smelting the ore. The Batsto River, the Mullica (Atsion) River, and Nescochague Creek furnished water power.[4]: 118 Immediately after his purchase from Wescoat, Read acquired additional wood and ore rights between Batsto and Atsion from John Estell, and then successfully petitioned the legislature for an act authorizing him to dam the Batsto River.[4]: 118–119 By the end of 1766, he had built the Batsto Iron Works, including Batsto furnace.[4]: 120

In 1773, John Cox bought the Iron Works, which produced cooking pots, kettles, and other household items. Batsto manufactured supplies for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.

In 1779, the Iron Works manager, Joseph Ball, bought the works and in 1784, his uncle, William Richards, bought a controlling interest. Over the next 91 years, the Richards family built most of the structures in the village. Richards was ironmaster until he retired in 1809. He was succeeded by his son, Jesse Richards, who ran the operation until his death in 1854 and was followed in turn by his son Thomas H. Richards. In the mid-19th century, demand for iron declined and Batsto turned to glassmaking, though without lasting success. Soon Batsto was in bankruptcy.

In 1876, Philadelphia businessman Joseph Wharton purchased Batsto along with a substantial number of other properties in the area. He improved many of the village buildings and was involved in a number of forestry and agricultural projects, including cranberry farming and a sawmill. After his death in 1909, his properties in the Pine Barrens were managed by the Girard Trust Company in Philadelphia.

Historic site

editBy the late 1930s, the houses in Batsto were "occupied chiefly by woodcutters and other members of South Jersey's forest people."[5] Starting in 1952, the Air Force reviewed the Batsto location for an arms depot. Included in that construction was a plan for a "trans-ocean airport" and Congress was working on authorizing $73,523,000 for the establishment of a combined depot and air transport service.[6] However, by 1956, the depot plans had shifted to Long Branch and the Air Force was no longer interested in this location. The state of New Jersey purchased the Wharton properties in the late 1950s and began planning the use and development of the property, allowing the few people still living in the Village to remain; in 1989 the last house was vacated.

After the property was purchased in 1958, the plans started with the restoration of the 50-room mansion and the rebuilding of the dam for recreation on the lake.[7] After work began the property was concurrently opened to visitors. In 1959 the historic village of Batsto became the most popular site for that year as measured by visitors relative to other state historic sites.[8] The historic village was dedicated on May 27, 1961 at 1:30pm.[9]

In 1961, the visitor center was started. It initially housed the office, information desk, museum and an auditorium.[10]

Today there are more than forty sites and structures, including the Batsto mansion, a sawmill, a 19th-century ore boat, a charcoal kiln, ice and milk houses, a carriage house and stable, a blacksmith and wheelwright shop, a gristmill and a general store. The Post Office is still in operation, and collectors have stamps hand-cancelled, with no zip code. The Batsto-Pleasant Mills United Methodist Church building, erected in 1808 as the Batsto-Pleasant Mills Methodist Episcopal Church, is still active as a place of worship.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Batsto". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Locality Search Archived 2016-07-09 at the Wayback Machine, State of New Jersey. Accessed March 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Pierce, Arthur D. (1957). Iron in the Pines. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-0514-3.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1955). New Jersey: A Guide to Its Present and Past. New York: Hastings House. p. 604.

- ^ Tug of War Starts in Location of Air Force Freight Depot, Asbury Park Press, May 17, 1952, Page 2

- ^ Bigger, Better Recreation Aim of New State Planning Chief, Asbury Park Press, March 16, 1958, Page 5

- ^ 87,000 Visit Colonial Site, Asbury Park Press, July 29, 1959, Page 1

- ^ Set Dedication of Batsto Area, Asbury Park Press, May 9, 1961, Page 11

- ^ Colonial Village Plans Outlined, Asbury Park Press, Oct 1 1961, Page 32